Barry Lyndon (1975) – Review by Stanley Kauffmann

Beautiful pictures are not film style. Kubrick’s latter-day work is solipsist and smug, isolated and sterile. For me Barry Lyndon is an anti-film, a gorgeous, stultified bore.

Beautiful pictures are not film style. Kubrick’s latter-day work is solipsist and smug, isolated and sterile. For me Barry Lyndon is an anti-film, a gorgeous, stultified bore.

Kubrick’s future shock satire, A Clockwork Orange, is twice the movie it was accused of being

In this essay on The Shining, Paul Miers asserts that “to understand Kubrick’s achievement one must attempt a reading of the mass-market book on which it is based.”

D’avance, nous savions que ce serait un événement. Parce que les dix millions de dollars dépensés garantissaient la qualité du spectacle et nous promettaient ce récital d’effets spéciaux, cette fête de l’imaginaire, ce plongeon dans l’inconnu dont le cinéma de SF nous frustre régulièrement.

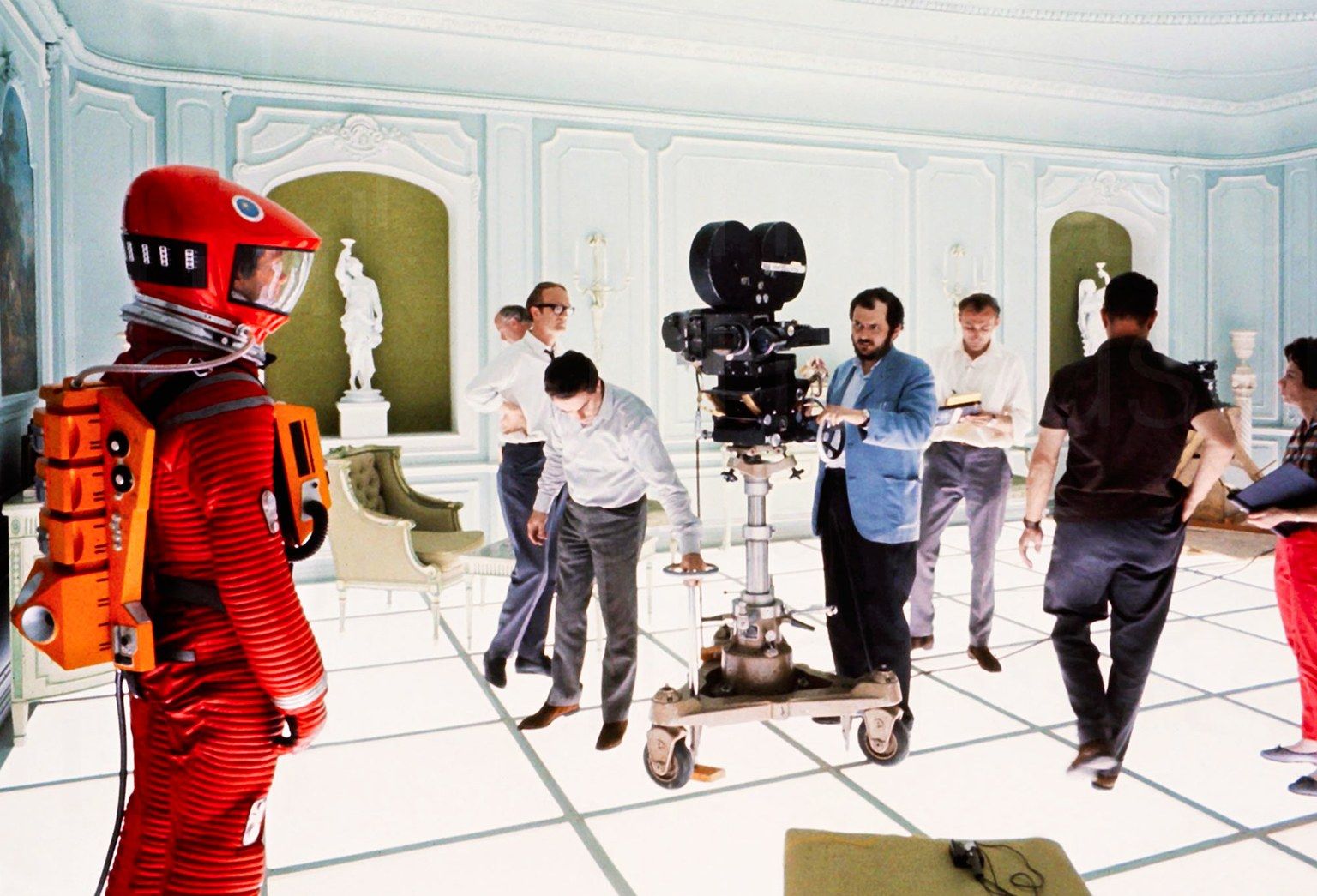

Stanley Kubrick was determined the design for his ‘definitive attempt’ at the science-fiction film should represent a decisive break with Hollywood norms — and who better to enlist to his cause than a pair of spacecraft consultants poached from the very heart of NASA itself?

These are four key scenes from the main sections of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that can be considered, with some reservations, a cinematic milestone in both the technical achievement and in its aesthetic exposition.

Given the grippingly bizarre settings and situations that Stanley Kubrick’s films favored, what could be more startling than the scene that opens “Eyes Wide Shut”? It’s only the sight of two people who resemble glamorous movie stars getting ready for a black-tie party.

Nicole Kidman is dawdling before the mirror, naked except for her eyeglasses and an earring that’s giving her trouble. She fusses with it, but languorously, as might be expected amid her gilded surroundings. They suggest the kind of hotel where each room is a scaled-down version of the queen’s bedchamber at Versailles. The lamps bathe Ms. Kidman in flattery…

In this essay, Sobchack explores Kubrick’s use of décor to emphasize the theme of violence in A Clockwork Orange

Barry Lyndon mette in scena una società violenta, ferocemente classista, dove l’avventuriero gode di una libertà effimera e viene presto emarginato e distrutto. Arricchito dalla più bella fotografia che si sia vista al cinema, il film comunica con stoicismo un sentimento amaro dell’esistenza e della storia.

Stanley Kubrick ha equamente ripartito il film tra un’immagine agghiacciante del futuro e il grigiore dell’establishment antiquato e cadente. Per ripeterci che l’uomo non può migliorare, il regista ha fatto riecheggiare il romanzo di Burgess in una cassa armonica dagli effetti stereofonici.

Paths of Glory finds Kubrick dealing in the wider realm of ideas with a relevance to man and society. Without casting off any of his innate irony and skepticism, the director declares his allegiance to his fellow men.

Nell’anniversario della morte di Stanley Kubrick, torna nei cinema nella versione restaurata uno dei suoi capolavori, 2001: Odissea nello spazio

Pauline believed she had a clear-eyed view of Kubrick’s intentions. At the end of the picture, when Alex’s former victims turn on him and he reverts to his old, corrupt self, she grasped that Kubrick intended it as “a victory in which we share . . . the movie becomes a vindication of Alex, saying that the punk was a free human being and only the good Alex was a robot.”

Kubrick’s virtuosity as a filmmaker, and the range of his subjects, have served to disguise his near-obsessive concern with these two matters—the brutal brevity of the individual’s span on earth and the indifference of the spheres to that span, whatever its length, whatever achievements are recorded over its course.

Fairy tales can come true. Spielberg the historian is in remission; Steven the regressive has returned, with a vengeance. An occasionally spectacular, fascinatingly schizoid, frequently ridiculous, and never less than heartfelt mishmash of Pinocchio and Oedipus, Stanley Kubrick and Creation of the Humanoids, Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence is less a movie than a seething psychological bonanza.

Tim Kreider, who also wrote an incisive article on Eyes Wide Shut (“Introducing Sociology”), here takes a brilliant stab at AI in a – rarely mentioned – piece that was originally published in 2002 in Film Quarterly

SUMMARY Spartacus is based on an historical figure and is the story of the rise and fall of a slave living in Rome before the

Aryan Papers is a project that was supposed to be directed and written by Stanley Kubrick but was never finished.

Stanley Kubrick, it appears, has raised many of the same questions through his films as Nathaniel Hawthorne did with his writing. In fact, they seem to share similar psychologically based images despite being separated by 100 years and Kubrick’s use of a medium that Hawthorne never experienced.

Vedere, rivedere, stravedere. Sarà possibile inventare uno «stravedere» come possibile ulteriore significato di «to overlook». In ogni caso, Shining è un film da vedere rivedere stravedere, portando la «stravisione» oltre l’intransitività dello «stravedere (per – qualcuno o qualcosa – )». Ed è un film che stravede il cinema e nel cinema, il futuro negli anni ’80.

Give me a brain – The cinema of the brain and the question of death (Kubrick, Resnais) – The two fundamental changes from the cerebral point of view – The black or white screen, irrational cuts and relinkings – Fourth aspect of experimental cinema

Since the recognized success of Dr. Strangelove, objections to Kubrick’s obscurity, his enigmatic mind, his bleak view of man, his simplistic view of life, his boring mannerisms abound in the reviews of his films. Barry Lyndon seems destined to encourage the same ambivalent critical reaction.

2001: A Space Odyssey is fascinating when it concentrates on apes or machines, and dreadful when it deals with the in-betweens: humans. For all its lively visual and mechanical spectacle, this is a kind of space-Spartacus and, more pretentious still, a shaggy God story.

Jack has consistently avoided the movie-star trap of appearing in a string of safe, conventional movies by involving himself with films made by off-center creative artists involved in honest efforts to put something new and daring on the screen.

Barry Lyndon non ha bisogno di chiamarsi Settecento. Se il titolo in Bertolucci indica l’intenzione astratta di definire storicamente quello che – dalla schematica situazione iniziale – si è riproposto come un film dai personaggi classici e «umani»; un film in cui della grandezza e casualità della Storia c’è solo la fluvialità del tempo e l’ampiezza della produzione (la storia economica del film), in Kubrick il nome – come si accennava – deve definire lo sparuto soggetto che è protagonista.

So Barry Lyndon is a failure. So what? How many “successes” have you seen lately that are half as interesting or accomplished, that are worth even ten minutes of thought after leaving them? By my own rough count, a smug little piece of engineering like A Clockwork Orange was worth about five. I’m reminded of what Jonas Mekas wrote about Zazie several years ago: “The fact that the film is a failure means nothing. Didn’t God create a failure, too?”

Da Nang è lontana da Montelepre. La storia di Salvatore Giuliano e la guerra del Vietnam non si consumano sotto lo stesso cielo. Ma, forse, le traiettorie della “blindatissima” Full Metal Jacket e la parabola fatale del Siciliano attraversano lo “stesso” cinema.

In this exclusive interview, Stephen King discusses his past work, his inspirations, his attitudes toward the genre, and his future projects.

Barry Lyndon is a leisurely, serious, witty, inordinately beautiful, premium-length screen adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s first novel, The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq., published in 1844 and set in the second half of the 18th century.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!