by Douglas Brode

Jack has consistently avoided the movie-star trap of appearing in a string of safe, conventional movies by involving himself with films made by off-center creative artists involved in honest efforts to put something new and daring on the screen. Certainly, Stanley Kubrick and The Shining rated as just such a director and film. The movie infuriated as many viewers as it satisfied. People who approached this as fans of the Stephen King novel (ardent aficionados consider King the rightful heir to Edgar Allan Poe) saw the film as a disastrous misrepresentation of his finest book, a big, cold, empty movie missing all the emotional horror; those who considered King’s novel nothing more than upscale pulp argued that the directorial genius of Stanley Kubrick transformed a clever if negligible book into a major work of the cinema. People who love horror films in general and ghost stories in particular were put off by the movie, which in fact pulls the rug out from almost every convention associated with such tales: people who scoff at such stories as simple-minded tripe were delighted by what they perceived as Kubrick’s devilishly unorthodox approach, satirically undermining the absurdities of the storyline.

That story begins as Jack Torrance (Nicholson), a former teacher and aspiring writer, applies for the position of caretaker at the vast Overlook Hotel, located in an isolated mountainous section of Colorado. A buzzing resort during the summer months, the place is kept closed during the winter; the general manager (Barry Nelson) confides to Jack that one previous caretaker, apparently driven quite mad by the isolation and emptiness, murdered his two small daughters with an axe. Then again, the man’s flight into murderous action may have had less to do with psychological causes than the hotel’s location, as it was unknowingly built over an ancient Indian burial ground; endless rumors abound that the ghosts of those native Americans still haunt the place, possessing the people who live there and spurring them on to awful deeds.

Jack, though, pays little attention to such information and is happy to be awarded the job, as it will allow him both the economic base and quiet solitude he desperately needs if he is to finish his great American novel. So he moves his wife (Shelley Duvall) and small son Danny (Danny Lloyd) into the enormous place. At first, everything seems fine: Danny whisks around on his tricycle. Wendy becomes a kind of caricature of the dutiful housewife and mother, while Jack pours himself into his writing with manic intensity. But there is another element, a supernatural side, to their life at Overlook. Each of the family members is subject to visions of spirits: the ghosts of the two murdered daughters, spooky images of tattered and terrifying creatures, walls that drip blood which eventually floods its way over everyone and everything. In time, Danny uses his unique clairvoyant gifts for seeing through space and time (an ability to “shine,” in the words of an elderly black cook, played by “Scatman” Crothers) to make connection with an imaginary friend named Tony, who has long been with him and now introduces Danny to the horrific forces hovering everywhere. Danny sees that his own father is surrendering to the evil in this place (“You are the caretaker.” A dark voice tells Jack, “and you have always been the caretaker!”), hinting that he is merely the latest incarnation of the hideous presence which previously took the lives of innocents.

Certainly, the cinematography and editing (along with the precise musical scoring) is dazzling, and some critics were overcome by Kubrick’s technical accomplishments. “The first epic horror film,” Newsweek’s Jack Kroll claimed. “[Kubrick] not only gets the horror, he gets the perverse beauty of horror,” praising Kubrick’s “love for the technical and formal sides of filmmaking.” In Time, Richard Schickel likewise praised Kubrick’s “stylistic mastery and rigorous intelligence,” congratulating him for “flouting conventional expectations of his horror film,” and insisting “it is a daring thing the director has done.”

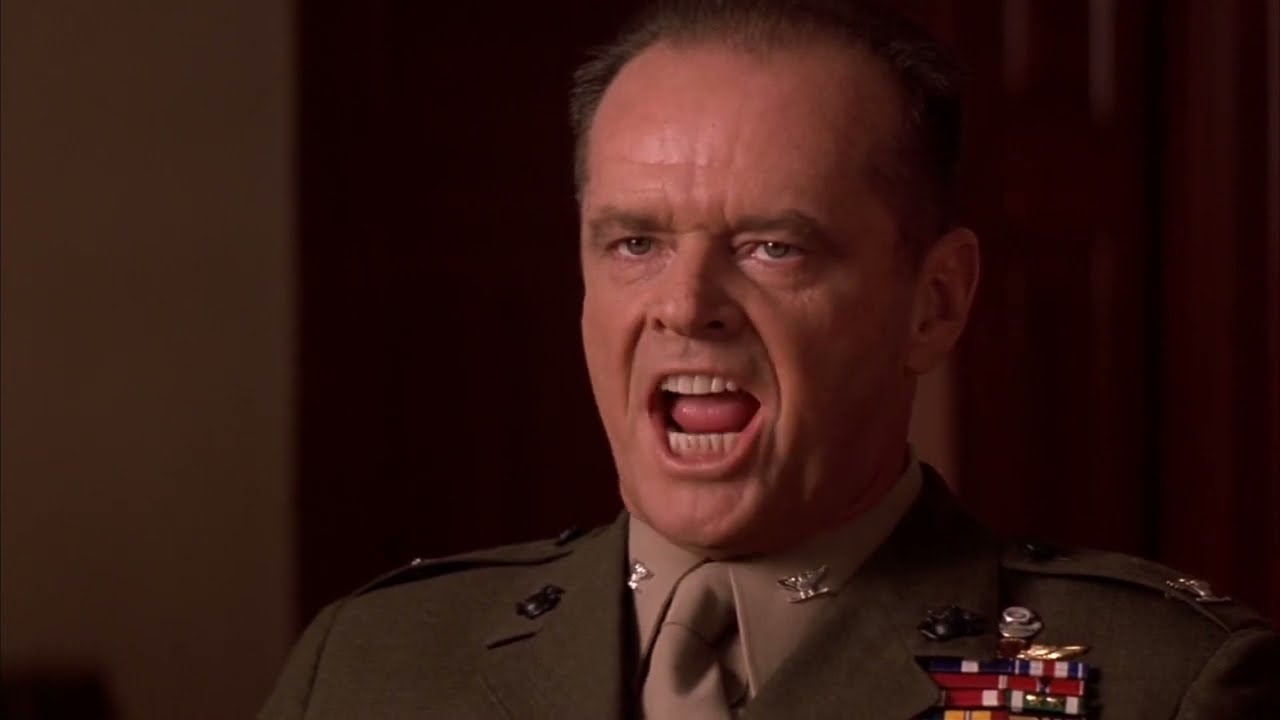

Those reviewers able to accept Kubrick’s approach to King’s novel also admired Jack’s acting. Kroll claimed that for “all [the film’s) brilliant effects, the strongest and scariest element in The Shining is the face of Jack Nicholson undergoing a metamorphosis from affectionate father to murderous demon.” Kroll also noted that Jack’s famed “killer smile,” so often an element in his various characterizations, here became the basis for the character: “The smile is the facial barometer by which we read the state of his soul as it’s sucked deeper and deeper into demonism by the black forces that infest the huge hotel. You suspect Kubrick cast Nicholson in the part chiefly because of that smile. Kroll was likewise able to accept the sudden flights into self-parody (in both Jack’s performance and in the film containing it) as basic to the directorial vision: “Nicholson’s Jack Torrance is a classic piece of horror acting: his metamorphosis into evil has its comic sides as well—which makes us remember that the devil is the ultimate clown.” Schickel concurred: “[Kubrick] has asked much of Nicholson, who must sustain attention in a hugely unsympathetic role, and who responds with a brilliantly crazed performance.”

Others, however, found the performance to be one of the least disciplined and most mannered ever delivered by Nicholson, usually a remarkably “realistic” actor. For such critics, the “gags” were offensively unfunny: the visual discovery by Wendy that Jack’s “novel” is nothing more than the single phrase “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” endlessly repeated but in diverse typographical arrangements; Nicholson’s extended Richard Nixon imitation; Jack’s delivery of the famous Tonight Show opening (“Heeeeeeeere’s Johnny!”) as he axes his way through a door to kill his wife. They constituted not an acceptable, even important, aspect of the film’s iconoclasm, but the ultimate proof that this was an immense and elaborate but empty film existing only to share a few strained, paltry gags, as such making an absolute travesty out of a workable horror novel. “Jack Nicholson,” John Simon of the National Review wrote, “harns atrociously from the outset.” Pauline Kael, often a Nicholson admirer, wrote in The New Yorker that, “There’s no surprise in anything he does, no feeling of invention. . . . Axe in hand and slavering, with his tongue darting about in his mouth, he seems to have stumbled in from an old A.I.P. picture.”

In Commonweal, Colin L. Westerbeck, Jr., pointed out: “The plain truth is that [Kubrick] has let Jack Nicholson run riot. Jack is made to seem dangerous and crazy before the family even moves to the Overlook Hotel,” which of course cuts away the edge of psychological thriller from the plot: We need to see him gradually go bonkers for the suspense to mount, but lie’s clearly bouncing off the walls even before their encounter with the evil in this place. King carefully hinted at the character’s predisposition for madness, then put him into precisely the situation that would step-by-step logically lead him down a dark path to just such a terrible state. Kubrick, apparently uninterested in such niceties of characterization or plot but fascinated by the newest developments in camera technology and sound editing, paid little attention to any narrative elements.

Or, as Kael wisely observed, “If The Shining is about anything, it’s tracking.” Simon argued the film’s failure grew out of Kubrick’s “basic inability to deal with people. … In two and a half wearying hours. The Shining fails to establish a single man. woman, or child.” Of course, this is where the film most markedly differs from the approach found m King’s novel, w here he delineated the personalities and psychologies of each protagonist, then created a drama in which their actions are true to what we know of them.

In the novel, for instance, we clearly understand Jack, not as some twisted tour-de-force for a great actor gone ovcr-thc-top but as a vulnerable, frustrated, confused, self-interested but not entirely unsympathetic man. Tire Jack of the book, hungry to create a great novel, becomes convinced the previous crime is the source of the master- work he was predestined to write, so lie understandably becomes obsessed with that crime. Yet there’s the problem of his modest gifts. Which is why, when Jack Torrance cannot get the story down on paper, he must objectify* the problem; knowing deep down it’s his own failure as a writer but unable to squarely face this. Jack searches for a scapegoat or. in his case, scapegoats. His family, in his mind, is the reason for his being unable to complete the masterwork. Combine this with the obsessive attention he has paid the past murders, and it makes a horrifying sense that the current caretaker would eventually follow the pattern established by his predecessor.

What happens, then, can be interpreted either as a ghost story or as a talc of psychological horror.

In the film, such intriguing ambiguousness gives way to arch horror antics. The flamboyant filmmaking does not function to communicate King’s ideas, but glides around them, just as Danny’s tricycle glides around the maze-like corridors of the hotel: moving fast but going nowhere. It rates, therefore, as style without substance, technique presented on attention-getting level. There is no content, in terms of character or drama, but rather the form becomes (for Kubrick, and those who can stomach his approach to film) the content. As Pauline Kael observed, “Kubrick loves the ultra-smooth travelling shots made possible by the Steadicam.” More, apparently, than he loves his characters. Kubrick—as critic Henry Bromell correctly stated—”simply makes Jack an exaggerated, highly stylized boogeyman rising from the shadows to frighten children.”

Jack, apparently, was gleeful at that possibility: “Within the next six months,” he announced in May 1980, “I will be something petrifying in between 10 and 100 million dreams.” He has, moreover, claimed he wanted the character to be even nastier than what we see, if that’s possible: He’d “have been a lot worse if I’d had my way. . . . What I liked about that guy was that he was so nuts that even before he was doing anything, lie liked scaring people. . . . Grand Guignol was that story’s classification for me.” On the other hand, lie’s also stated that, at various points during the shooting, he would stop a take to nervously ask: “Jesus, Stanley, aren’t I playing this too broad?”

Certainly, the experience of shooting this film was unique. Jack learned that Kubrick shoots the simplest of sequences over and over again until somehow, some way, something special happens, lending an otherwise mundane scene a unique edge. Afterwards, co-star Crothers recalled: “He had Jack Nicholson walk across the street, no dialogue. Fifty takes. He had Shelley, Jack and the kid walk across the street. Eighty-seven takes, man. He always wants something new and he doesn’t stop until he gets it.” The film was proceeded by a string of stories detailing the difficulty on the set between Nicholson and Kubrick. “I’m a great off-stage grumbler.” Jack later told Newsweek. “I complained that he was the only director to light the sets with no stand-ins. We had to be there even to be lit. Just because you’re a perfectionist doesn’t mean you’re perfect.”

But Nicholson’s own preference for people movies (and directors who do them with a minimum of visual flamboyance and a maximum of concentration on characterization) suggests he must on some level have been aware of the essential hollowness of The Shining. He was not specifically speaking of Kubrick (though he might well have been) when he told Gene Siskel in 1974 why he loved doing The Last Detail: “I think we’ve had a long period in the movies where fancy editing and tricky camera movements have been the fashion. I suspect and hope that very soon the only unusual element in a movie- will be its characters. After the audience has been sufficiently shocked by special horror effects, explicit sexual fantasies, and endless brutality, what you’re going to have is what you used to have, which is unusual people behaving in interesting and hopefully illuminating ways.” In The Shining, he appeared in the kind of fancy/tricky film he had five years earlier condemned.

Yet Jack’s attraction to the part was understandable, considering its autobiographical element. Jack Torrance marks the first time Nicholson has shared the first name with one of his characters, and Torrance serves as a kind of doppelgänger for Nicholson, a nightmare vision of what he himself might have become had his career not gone so well. The image of Torrance with his phoney grins as he tries to get the job doubtless derives authenticity from Nicholson’s memory of how demeaning it felt to go out on casting calls as an unknown actor, smiling ingenuously at people who would probably reject him. The intensity of Torrance’s frustration as he tries to write something worthwhile, and his enormous anger at his family when they disturb him, grew from Jack’s oftentimes frustrated attempts to write while still married to Sandra Knight. “That’s the one scene in the movie I wrote myself,” Jack confided to the New York Times in 1986, “that scene at the typewriter. That’s what I was like when I got my divorce. I was acting in a movie in the daytime and writing a movie at night and my beloved wife walked in on what was, unbeknownst to her, this maniac—and I told Stanley about it and we wrote it into the scene. I remember being at my desk and telling her, ‘Even if you don’t hear me typing it doesn’t mean I’m not writing.’ I remember that total animus. Well, I got a divorce.”

The joke concerning the worthlessness of Torrance’s “creative” work may be viewed as Nicholson’s (and, for that matter, every author’s) deep-down fear that what he turns out at the typewriter is thin and insignificant: “I used to write, so I understand this guy’s writer’s block.” And the difficult, demanding role of father is basic not only to this film but to so many of the projects Jack (with his lifelong ambivalence about father figures) has been drawn to. Jack confesses to having had an imaginary playfriend as a child, just as Danny does here.

Jack’s vision of the ultimate evil as appearing in the guise of Richard Nixon reflects his own politics (“Personally, I impeached Nixon long ago,” he said during Watergate). Even the fact that many of Torrance’s visions in the hotel are from the 1920s (“spectral revelers right out of The Great Gatsby,” Kroll commented) adds to this autobiographical element, for Jack has always been personally “haunted” by The Great Gatsby. Torrance’s drifting through life can be viewed as a parallel to Jack’s own earlier inclinations in that direction, while “Daddy” Torrance’s hinted-at problems with alcohol struck a chord for Jack, having been brought up by a father-figure who suffered from drinking problems. Finally, Torrance is the ultimate example of the character who leads a double-existence: loving father and axe-murderer; middleclass provider and struggling artist; caretaker and writer; Jack Torrance and some other man from out of the past.

For trivia buffs, one further bit of information is imperative: Love it or hate it, the “Heeeeere’s Johnny!” line was Jack’s (ever the collaborator!) idea. “Stanley lives in England.” Nicholson once said, “so he didn’t really know what it meant.”

Source: Douglas Brode, The Films of Jack Nicholson, Citadel Press, 1987; pp. 205-211