Megalopolis – A Lifetime Dream | Review

Coppola’s Megalopolis, a decade-long project, debuts at Cannes, facing mixed reactions. The film blends epic ambition and innovative storytelling, challenging conventional cinema.

Coppola’s Megalopolis, a decade-long project, debuts at Cannes, facing mixed reactions. The film blends epic ambition and innovative storytelling, challenging conventional cinema.

Farcical, baroque, pompous, obsessed with time: the latest grand film by Francis Ford Coppola is yet another kamikaze love letter to cinema

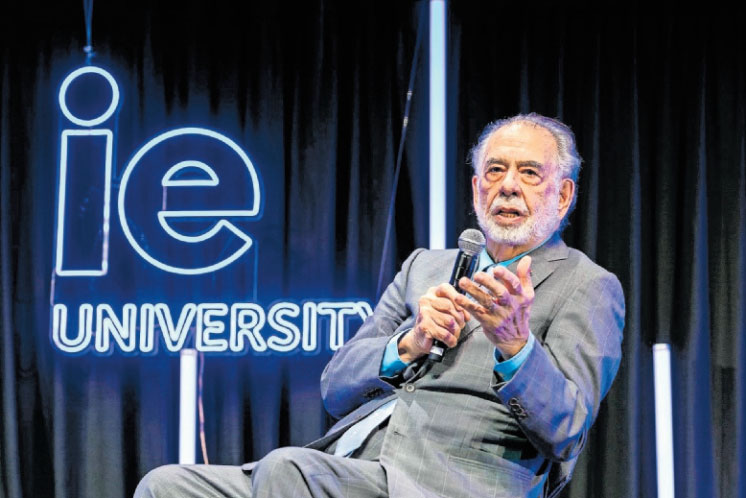

El director estadounidense, de 84 años, reflexiona sobre las humanidades y el cine en la era de la inteligencia artificial

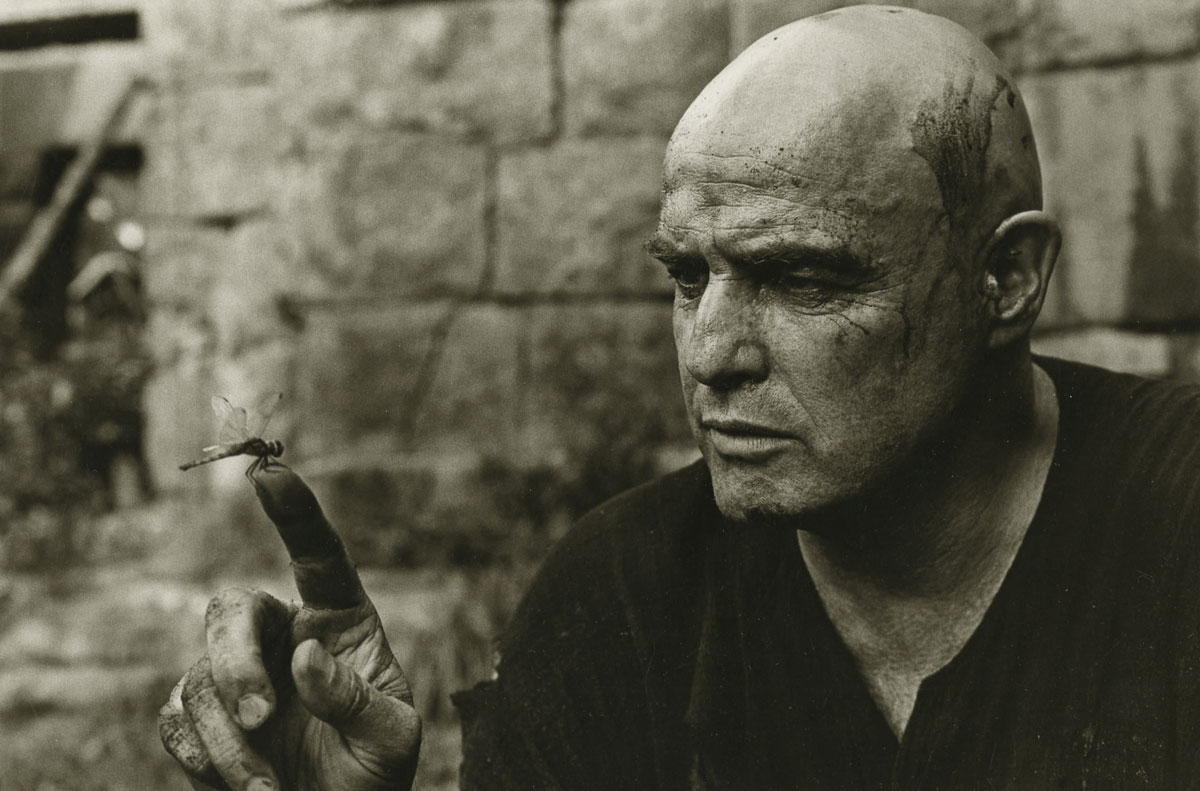

When I read three years ago that Vittorio Storaro had been chosen as the cinematographer for Apocalypse Now, I was shocked. Storaro, the lush Vogue-style photographer of Last Tango in Paris and The Conformist, for a picture that was being billed as the definitive epic about Vietnam!

However distant it may seem at first glance, Apocalypse Now remains not only deeply indebted to Conrad’s tale but not fully comprehensible without reference to it

In The Power of Adaptation in “Apocalypse Now” Marsha Kinder critically compares and contrasts the film and the novel. In this article, Kinder states that “Coppola rarely hesitates to change Conrad’s story-setting, events, characters-whenever the revision is required by the Vietnam context.”

The Godfather bore witness to the bitter truth: evil, hydra-headed, renews itself and triumphs in the end; in America, the Corleones win.

Francis Ford Coppola and Gay Talese conversation on friends, censorship, death, and money

What does Apocalypse Now mean—the film as we have it, considering the minimal difference between the 35mm version with the title sequence and the 70mm version without, but ignoring all the prerelease stories and versions, preliminary scripts, and encrusted commentary?

Pauline Kael reviews ‘New York Stories’, the 1989 anthology film consisting of three shorts with the central theme being New York City. Episodes directed by Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Woody Allen.

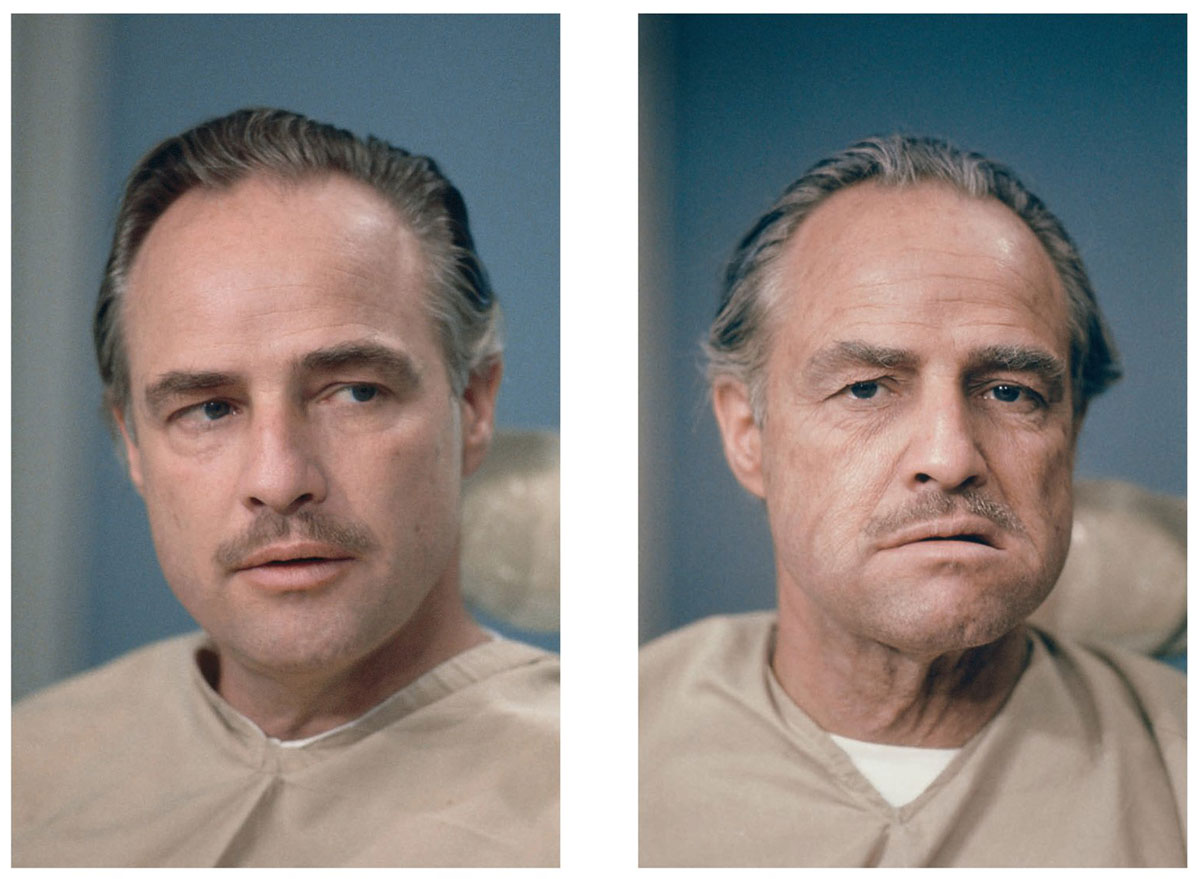

Hurricane Marlon is sweeping the country, and I wish it were more than hot air. A tornado of praise—cover stories and huzzahs—blasts out the news that Brando is giving a marvelous performance as Don Corleone in The Godfather, the lapsed Great Actor has regained himself, and so on. As a Brando-watcher for almost 30 years, I’d like to agree.

The Godfather II is a sequel to a film whose narrative drive and choreographed violence made it one of the better genre films of recent years. It is colder, more severe, less violent and much more ambitious than the original The Godfather.

There’s nothing fun or funny to be found here. It offers us only the absorption of good acting and good storytelling combined with a plausible anthropology of a strange, terribly relevant culture. What more could we possibly want from a movie? How often, these days, do we get anything like all that?

And then there was Marlon Brando, against all the odds, cast in one of filmdom’s juiciest roles, as mob chief Don Vito Corleone. He was eased in, despite stiff opposition from the studio brass, because of the advocacy of a thirtyish fan, Francis Ford Coppola, an Italian-American who happened to be the director of The Godfather. Once he got the part, Brando in turn helped Coppola maintain camaraderie during the frenzied three-month shooting by kibitzing with the cast and establishing a fatherly relationship.

Inflation does not always assure survival. My guess is that three years from now we will still remember scenes from Raoul Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties (1939) while The Godfather will have become a vague memory.

The Godfather is, furthermore, and by critical consensus, a stunning confirmation of my claims for Coppola’s talents: vividly seen, richly detailed, throbbing with incident and a profusion of strikingly drawn characters

A wide, startlingly vivid view of a Mafia dynasty, in which organized crime becomes an obscene nightmare image of American free enterprise. The movie is a popular melodrama with its roots in the gangster films of the 30s, but it expresses a new tragic realism, and it’s altogether extraordinary.

Coppola’s “heart of darkness,” like Conrad’s, is a triumph of style over story. Or rather, the description—words for Conrad, mise-en-scène for Coppola—is the story’s raison d’être.

by Marjorie Rosen In Hollywood circles the adage, “You’re as good as your last picture,” holds more truth than is comfortable or healthy. It could

Apocalypse Now achieved its highest aspiration: Not only was it immersed in the historical period and place – Vietnam – but it was an allegory of people facing reality and truth.

Certain films contain what I shall call “operatic montage,” a form of montage which manipulates temporal and spatial relations in film, typically to melodramatic ends.

Throughout the three hours and twenty minutes of Part II, there are so many moments of epiphany — mysterious, reverberant images, such as the small Vito singing in his cell — that one scarcely has the emotional resources to deal with the experience of this film.

“The Conversation” was very ambitious, and I hung in not because it was going right, but because I couldn’t accept within myself the judgment that I couldn’t succeed in doing it. It’s a funny thing, but I just couldn’t let the project go.”

by Andrew Sarris I It came over the car radio while I was driving out to wintry, stormy Long Island for the Memorial Day weekend.

I am convinced that The Godfather could have been a more profound film if Coppola had shown more interest (and perhaps more courage) in those sections of the book which treated crime as an extension of capitalism and as the sine qua non of showbiz.

Mark Seal recalls how the clash of Hollywood sharks, Mafia kingpins, and cinematic geniuses shaped the Hollywood masterpiece ‘The Godfather’

Transcript of Mario Puzo’s 1970 letter to Marlon Brando telling him he was the only actor who could play Don Corleone

Janet Maslin reviews Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘The Godfather’. Published in Boston After Dark, 1972 March 28

by Pauline Kael At the end of The Godfather Part II (1974), the story was complete—beautifully complete. Francis Ford Coppola knew it, and for over

Giacomo R. Carioti incontra a Roma il giovane produttore del ‘Padrino’, Albert S. Ruddy, con cui ricostruisce la storia del film

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!