by Andrew Sarris

It seems that the first question everyone asks about The Godfather is concerned with Marlon Brando’s interpretation of the title role. That is the way the movie has been programmed and promoted. Brando, Brando, Brando, and more Brando. The word from advance hush-hush screenings was wow, all caps and explanation point. More exclamation, in fact, than explanation. More than one whisperer intimated that Brando’s make-up (by Dick Smith, the auteur also of Dustin Hoffman’s Shangri-La face furrows in Little Big Man) was so masterly that the Brando we all know and love had disappeared completely beneath it. I must admit that some of the advance hype had gotten to me by the time I sat braced in my seat for the screening of The Godfather. I was determined to discern Brando beneath any disguise mere humans could devise.

The picture opened with a face outlined against a splotched blue background with no spatial frame of reference, a background no so much abstract as optically mod with a slow zoom to take us into the milieu by degrees. But that face! I was stunned. How had Brando managed it? The eyes, the ears, the nose, the chin. It didn’t look anything at all like Brando. And the voice was equally shattering in its unfamiliar pitch. I began groping for adjectives like “eerie” and “unearthly.” Gradually the face began to recede into the background, and I heard a familiarly high-pitched voice somewhere in the foreground. I suddenly recalled the plot of the novel and thus I realized that the face looming in front of me did not resemble Brando’s simply because it wasn’t Brando’s. (I learned later that the face and voice in question for the role of Bonasera belonged to a 20th-billed actor named Salvatore Corsitto who gets no points for looking like himself.)

When Brando himself finally materialized on the screen as Don Vito Corleone, I could see it was Brando all the way. There was no mistaking the voice even with the slow-motion throaty whine Brando used to disguise it. Brando’s range has always been more limited by his voice than his Faustian admirers cared to admit. That is why his best roles have always played against the voice by negating it as a mechanism of direct communication. Brando’s greatest moments are thus always out of vocal sync with other performers. Even the famous taxicab scene with Rod Steiger in On the Waterfront operates vocally (though not physically or emotionally) as a syncopated Brando soliloquy, a riff on the upper registers of sensitivity and vulnerability resonating all the more in counterpoint to Steiger’s more evenly cadenced street glibness and shrillness. Curiously, Brando has come to embody, often brilliantly, a culturally fashionable mistrust of language as an end in itself. The very mystique of Method Acting presumes the existence of an emotional substratum swirling with fear and suspicion under every line of dialogue. Hence, it is surprising that Brando has not played gangsters more often. The Machiavellian bias of the Method is ideally suited to the ritualized conversations of organized criminals.

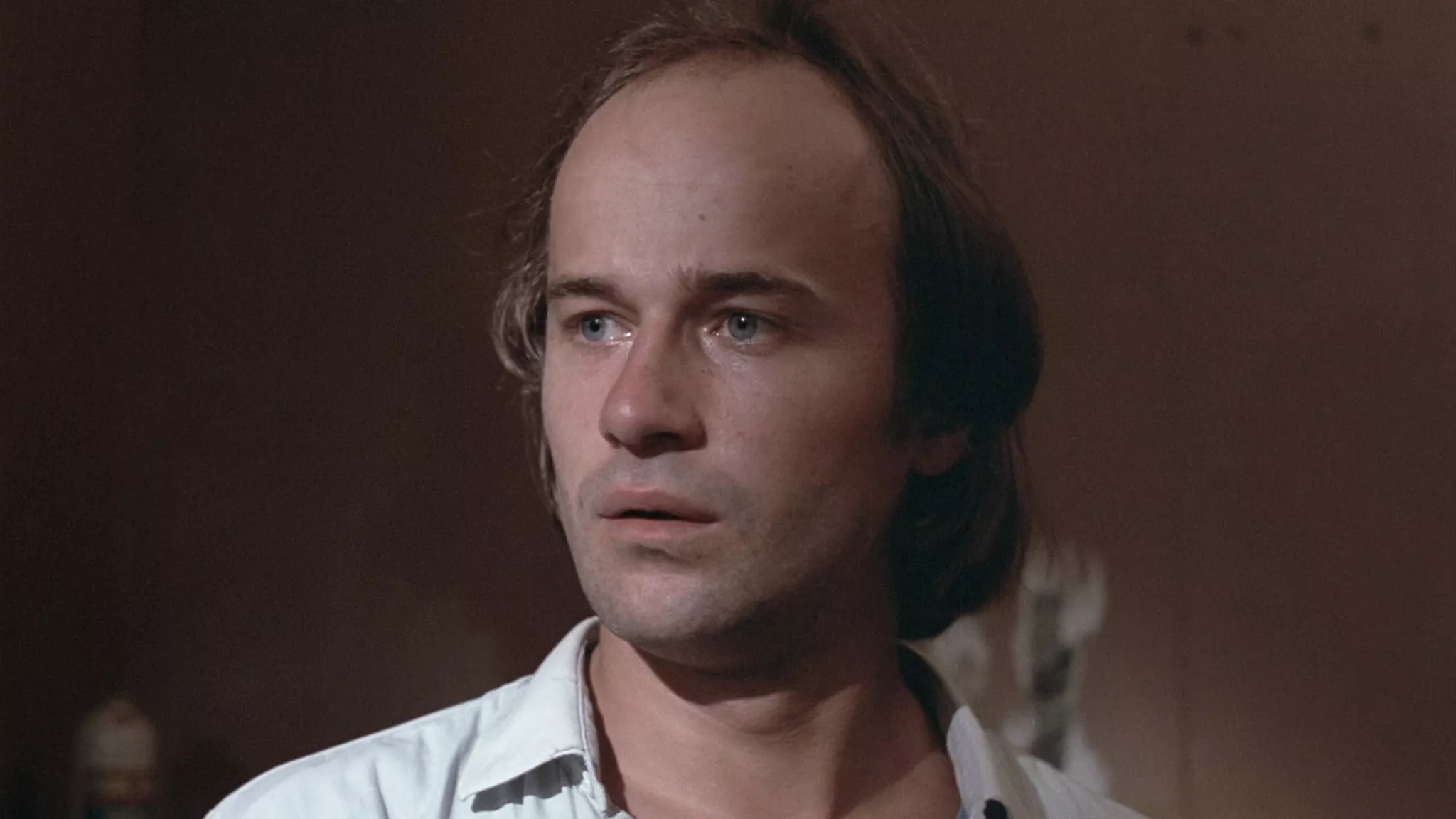

So to answer belatedly the first question everyone asks about The Godfather: Brando gives an excellent performance as Don Vito Corleone, a role Lee J. Cobb could have played in his sleep without any special make-up. Brando’s triumph and fascination is less that of an actor of parts than of a star galaxy of myths. Which is to say that he does not so much lose himself in his part as left his part to his own exalted level as a star personality. The fact remains, however, that though Brando’s star presence dominates every scene in which he appears, the part itself is relatively small, and there are other people who are equally good with considerably less strain, among them the extraordinarily versatile James Caan as the hot-headed, ill-fated Sonny Corleone, Richard Castellano as the jovially gruesome Clemenza, and Robert Duvall as Don Vito Corleone’s non-Italian consigliere, Tom Hagen. Al Pacino as Michael Corleone has much the biggest and most challenging role in the film, and gives the most problematical performance. It is with Pacino’s role that fact and fantasy come most discordantly into conflict. And it is with the characterization of Michael Corleone that both director-scenarist Francis Ford Coppola and novelist-scenarist Mario Puzo seem to drift away from the rigor of the crime genre into the lassitude of an intellectual’s daydream about revenge without remorse and power without accountability.

There were many ways to adapt Puzo’s novel to the screen. (There is no question here of fidelity to a text that was merely the first draft of a screen treatment.) Puzo quotes Balzac no less in a foreword conveying a Brechtian implication: “Behind every great fortune there is a crime.” Brando claims to have been representing a typically corporate personality from the ruthlessly American capitalistic system. But The Godfather as a whole does not sustain this particular interpretation as effectively as did Kurosawa’s The Bad Sleep Well some years ago. That is to say that Kurosawa and his scenarists came much closer to conjuring up the quasi-criminal ruthlessness of a conglomerate like ITT than do Coppola, Puzo, and Brando. Coppola’s approach tends to be humanistic, ethnic, and almost grotesquely nostalgic. There is more feeling in the film than we had any right to expect, but also more fuzziness in the development of the narrative. The Godfather happens to be one of this movies that can’t stay put on the screen. There are strange ghosts everywhere like Richard Conte’s authentically Italian gangster kingpin Barzini evoking memories of House of Strangers and The Brothers Rico, and Al Martino as Johnny Fontane (alias Frank Sinatra) reportedly walking off the stage of a New York supper club just before The Godfather opened and apparently disappearing into that thick mist of forbidden fictions.

The Godfather is providing additional ammunition, if indeed any were still needed, for the kill-kill-bang-bang forces in the film industry. No, Virginia, this will not be still another article on violence in the movies. The lines forming for The Godfather can speak for themselves. What interests me at the moment is less the apparently insatiable hunger of the masses for homicide than the curiously disdainful attitude affected by the popgunnery purveyors toward their material. Gordon Parks, for example, refers derisively to Shaft (and, I suppose, the upcoming son of Shaft) as the kind of popular entertainment he must concoct in order to obtain the opportunity to do more serious work. Since Mr. Parks displays no discernible talent in private-eye melodrama, it is to be hoped that he obtains more “serious” assignments as quickly as possible. Similarly, Francis Ford Coppola has made it abundantly clear that The Godfather was undertaken quite consciously as a “compromise” with the commercial realities of the film industry. And now even Mario Puzo is making noises to the effect that The Godfather was written merely to provide the freedom and leisure necessary to turn out something comparable to The Brothers Karamazov. Tant pis and all that when we recall that there have been at least a score of gangster movies that have been artistically superior to any of the film versions of Karamazov.

Not that there is anything now about the Puzo-Coppola brand of voluptuous Faustianism, which might be subtitled: I sold my soul to the devil for filthy lucre and the roar of the crowd, but I still have my eye on the higher things. John Ford was eulogized through the thirties for turning out three commercial flicks like Wee Willie Winkie for the moguls in order to pay for any one serious film like The Informer for the mandarins. In retrospect, Wee Willie Winkie was never all that bad, and The Informer was never all that good. But Faustianism has continued to flourish even to this depressed day when Hollywood swimming pools are hard to come by or even the most corruptible radicals. No one seems to have learned the hard lesson of movie history that the throwaway pictures often become the enduring classics whereas the noble projects often survive only as sure-fire cures for insomnia. Not always, of course, but often enough to discourage the once fashionable game of kitsh-as-catch-can.

That The Godfather is almost fatally tainted with condescension follows almost logically from the revelation that the Coppola-Puzo second choice for the title role (after Brando) was none other than Sir Laurence Olivier. There’s nothing like a classy performer to get the public’s mind off the questionable cultural credentials of a popular subject. Still, publicity is publicity, and I have no desire to single out Coppola or Puzo for derision. Any artist is vulnerable enough in the journalistic jungle to claim the privilege of saying that he is saving his best for some later project still safely beyond the claws of the snarling critics. Coppola, particularly, has done good work in the past. His first film, Dementia 13, is unknown to all but the most dedicated archaeologists of American-International Corman horrifics. Coppola’s official first film, You’re a Big Boy Now, was completely eclipsed by Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. What I said at the time (in The American Cinema) is still pertinent: “Francis Ford Coppola is probably the first reasonably talented and sensibly adaptable directorial talent to emerge from a university curriculum in filmmaking. You’re A Big Boy Now seemed remarkably eclectic even under the circumstances. If the direction of Nichols on The Graduate has an edge on Coppola’s for Big Boy, it is that Nichols borrows only from good movies whereas Coppola occasionally borrows from bad ones. Curiously, Coppola seems infinitely more merciful to his grotesques than does anything-for-an-effect Nichols. Coppola may be heard from more decisively in the future.”

Since 1967 Coppola has been heard from with varying degrees of decisiveness in two commercial disasters—Finian’s Rainbow and The Rain People. Coppola had set up his own studio in the San Francisco area to revolutionize what was left of Hollywood. He sponsored George Lucas’s THX-1138 and was informally associated with John Korty in what might be called the San Francisco School of lyrical realism and dissonant humanism. Finian’s Rainbow was a hopelessly anachronistic project to begin with, a moldy bone to the blacks tossed by self satisfied liberals of the forties in the mistaken belief that bigotry was confined to that picturesque terrain South of Shubert Alley. Coppola did his best with Petula Clark and the badly miscast Fred Astaire, but the show simply sank into the realistic landscape. Another compromise perhaps? Certainly, Coppola’s heart was more completely committed to The Rain People, an itinerant production of uncommon emotional intensity.

I met Coppola at Bucknell when he was making The Rain People aboard a land yacht, traveling, as it were, across the real face of America in search of sociological truth with an improvised scenario. I remember being as impressed by Coppola’s intelligence as I was suspicious of his professed intentions. People who go out looking for America always seem to know in advance what they are going to find. Alienation and Anomie, Loneliness and Lethargy, Late Night Whining and Daily Paranoia. Coppola never succeeded in establishing the characterization of Shirley Knight’s wandering wife, and thus his narrative drifted without a psychological rudder. Still, the wife’s encounters with James Caan’s punchy jock and Robert Duvall’s sympathetically lecherous slate trooper lifted the film to the behavioral heights (and fights) of Petulia and Point Blank, two of the more brilliant explosions of the San Francisco area, if not of the San Francisco school, the formal sublimity of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo representing, of course, a different tradition altogether.

The failure of The Rain People and THX-1138 and the Korty films can be attributed partly to the inability of the traditional distribution and exhibition patterns to funnel a new kind of audience that is presumably panting for it. Or is there really that much of a new audience for movies? Whatever the explanation, Coppola had the satisfaction of having established his artistic identity as a director at the cost of his commercial solvency as a producer. He therefore approached The Godfather less as a creative opportunity than as a crutch for his stumbling career.

I am convinced that The Godfather could have been a more profound film if Coppola had shown more interest (and perhaps more courage) in those sections of the book which treated crime as an extension of capitalism and as the sine qua non of showbiz. Much of the time spent boringly in Sicily might have been devoted to the skimming operations in Las Vegas, and to the corporate skullduggery in Hollywood. A very little bit of the corrosively Odetsian wit of the fifties in The Big Knife and Sweet Smell of Success could have gone a long way here in relating the Mafia to our daily life. Instead, Coppola has taken great pains to make The Godfather seem like a period piece. Antique cars, ill-fitting clothes (especially for lose framed Diane Keaton’s WASP wardrobe), floppy hats, vintage tabloid front pages featuring dead gangsters of a bygone era all contribute to Coppola’s deliberate distancing tactics. Worst of all is the sentimental distinction between the good-bad guys and the bad-bad guys on the pseudoprophetic issue of narcotics distribution.

The production stories connected with The Godfather seem to take pride in the concessions granted to organized crime so that the film could be shot on New York locations without being shot up and shut down. Hence, there is no reference to the “Mafia” as such or to the “Cosa Nostra” as such, but merely to “The family.” It is as if producer Albert S. Ruddy were trying to enhance the diabolical reputation of his subject so that audiences would feel the chill of gossipy relevance. Since The Godfather is about as unkind to the Mafia as Mein Kampf is to Adolf Hitler, it is hard to understand why the local little Caesars didn’t pay Ruddy a commission for all the free publicity. However, even if Ruddy had not made all his noble sacrifices to the Mob for the sake of his muse, it is fairly certain that a realistic director like Coppola would have insisted on shooting his scenario on authentic locations. After all, wasn’t that the whole point of Coppola’s original safari from Hollywood to San Francisco: to escape from Hollywood’s synthetic sound stages and infinitely illusionist set designers?

And so we see Al Pacino and Diane Keaton walking out of the Radio City Music Hall ostensibly during the Christmas Season of 1945. How do we know it is 1945? The marquee has been made up to advertise Bing Crosby and Ingrid Bergman in The Bells of St. Mary’s. And here we have one of the paradoxes of plastic realism. It just so happens that I saw The Bells of St. Mary’s at the Music Hall in 1945, and the scene Pacino so painstakingly recreates before my eyes is false and strained in every way except the most literal. As the production notes tell us, “crowds gathered to stare at the old-time automobiles and ancient taxis with the legend ’15 cents for first 1/2 mile’ fare rates painted on the doors. Meanwhile, ushers ran up and down the street informing the public that the film playing was Elaine May and Walter Matthau in A New Leaf and the stage show was the 1971 Easter Show.”

Nonetheless, the plastic realism of the marquee and the old cabs cannot compensate for the sociological distortion of the empty sidewalks and the absent hustle and bustle. Around Christmas of 1945 at the Music Hall was a pretelevision festive crowd tableau such as we shall never see again in our lifetime. An old-time Hollywood illusionist like Vincente Minnelli would have captured the populist lilt of that moment whereas Coppola has captured only the plastic lint. Minnelli’s vision would have been that of the warm animal kingdom whereas Coppola’s is merely that of the cold mineral.

Similarly, few of the “more than 120 locations around Manhattan, the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Richmond” justified the trouble they took with any special aura of authenticity. Indeed, too often the studied and constricted framing of the “real” location only emphasized the artifices of the scenario. So little of Mott Street is utilized for gunning down Brando that the entire effect could easily have been reconstructed on a back lot. Location shooting has always been more of a Pandora’s Box than realistic pundits have ever wanted to admit. If I see one more set of play-actors cruising around the canals of Venice with all the natives looking for the camera (or for Erich Segal on one of the gondolas), I shall sing “O Solo Mio” a cappella. To escape from the alleged tyranny of the set it is necessary to conceive a much looser scenario than any now envisaged for most movies.

As it is, Coppola spends much too much lime savoring each location as if he were afraid audiences might not sufficiently appreciate its authenticity There is remarkably little elision of movement for a modern (or even a classical) movie. People walk through rooms, clump, clump, clump, as if they were measuring the floor for a rug. At times I would have welcomed even a wipe to jolly things along with page-turning dispatch.

Coppola’s treadmill technique is merely a symptom of his sense of priorities. The trouble began with the scenario’s lack of concern for the characters it could not wait to slaughter. The first murder is a genuine shocker, not simply because of its bizarre choreography (even more gruesome than in the book), but also because even alter the unexplained first murder in The French Connection, we are still not accustomed to having people we barely know bumped off on the screen. Puzo always provided a background dossier on his victims in his novel, and some objective mechanism for doing these dossiers a la The Battle of Algiers might have been devised for the movie. Coppola prefers to skim the surface of the novel for violent highlights, and thus discard all the documentation. However, it has been my impression that the rumored involvement of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin in the narrative was the big talking point of the novel. Who cares that much about Joe Profaci and his brood except on the mythic level of glorified gangsterdom? By contrast, Sinatra and his colleagues and conquests have always provided the stuff of forbidden fantasies for precisely the type of urban wage-slave that stands on line to see The Godfather. After Vegas and Hollywood, how can you keep ’em down on Long Beach?

Coppola does his best to narrow the focus of The Godfather to manageably monstrous proportions. His film is neither tragedy nor sociology, but a saga of monsters with occasionally human expressions. Even the irony of invoking the “family” as the basic social unit is not pursued beyond a desultory conversation between Michael (Al Pacino) and Kay Adams (Diane Keaton). The irony is not that the Corleone family is a microcosm of America, but rather that it is merely a typical American family beset by the destructively acquisitive individualism that is tearing American society apart. It is an idea that Chaplin developed so much more profoundly in Monsieur Verdoux: that if war, in Clausewitz’s phrase, is the logical extension of diplomacy, then murder is the logical extension of business. This notion is mentioned here and there in The Godfather, but never satisfactorily developed. There is simply no time. Another shot, another murder. And the crowds are keeping a box-score on every corpse. Let’s not disappoint them with a meditation on machismo and materialism. We can do that on the next picture, the “serious” one, the one the crowds will stay away from in droves.

The Village Voice, March 16, 1972, Vol. XVII, No. 11