by Joseph Gelmis

As president of Paramount Pictures, I must tell you now that under no circumstances will Marlon Brando appear in The Godfather. And, as president, I no longer wish to waste the company’s time even discussing it.

—Famous last words: Stanley Jaffe, ex-president of Paramount.

And then there was Marlon Brando, against all the odds, cast in one of filmdom’s juiciest roles, as mob chief Don Vito Corleone. He was eased in, despite stiff opposition from the studio brass, because of the advocacy of a thirtyish fan, Francis Ford Coppola, an Italian-American who happened to be the director of The Godfather. Once he got the part, Brando in turn helped Coppola maintain camaraderie during the frenzied three-month shooting by kibitzing with the cast and establishing a fatherly relationship.

Coppola, a graduate of Hofstra and the UCLA film school, had always wanted to work with Brando “for all those reasons that people who are thirty-two want to work with him. He had meant a lot to me when I was eighteen and just starting. So I finally came to the conclusion: ‘Well, what if we just got the greatest actor in the world and say to him: Create the Godfather.’ ”

Both Coppola and producer Al Ruddy speculated about Brando and Laurence Olivier. Olivier was the right age, but sick. Brando was only forty-seven, but he had perfected the New York accent (as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront), which Coppola felt was the basis for the godfather’s Italian-American dialect.

“I was desperate to give the film a kind of class,” said Coppola. “I felt the book was cheap and sensational. Mario Puzo [the author] said: ‘I always had Brando in mind when I was writing The Godfather.’ Coppola called Brando, asked him to read the book and judge if he wanted to play the sixty-two-year-old man.”

At Paramount. Coppola mentioned that he had called Brando. “It caused an explosion that almost got me fired on the spot. Shouting and yelling. I was really embarrassed. Ruddy was sort of intrigued with it. But the official family got very upset.” That was on a Friday.

On Monday, Brando told Coppola he thought he might like the part. Brando’s name was therefore put forth again by Coppola at the casting conference. There was another blow-up. And Jaffe delivered his ultimatum. (Jaffe quit during the filming of The Godfather, in part, according to reports, because he was outraged by Ruddy’s agreement with the Italian-American Civil Rights League not to use the words “Mafia” or “Cosa Nostra” in the film and also because he was tired of executive group-think and wanted to go back to independent producing.)

Before that meeting broke up, Coppola persuaded the rest of the Paramount brass, including Gulf & Western Board Chairman Charles Bluhdorn, to hear his five-minute pitch for Brando. “I explained how the mystique Brando had as an actor amongst other actors would inspire precisely the right kind of awe that the character of Don needed.”

He was told he could proceed, on three conditions: that Brando take no salary; that he shoot a screen test, and that he guarantee with his own money that the film would not go over the budget because of his exploits. Insiders believe that Brando may have gotten, finally, as much as $50,000, which is a fraction of his usual fee. His percentage of the net profits could earn him upwards of $1,250,000.

The feeling at Paramount, shared by industry officials, was that Brando ought to be grateful, since he had a reputation for being difficult and had not had a box-office hit in a decade. Coppola did not mention the terms to Brando when he went to his home in California to shoot a videotape test so Brando could see himself as an old man.

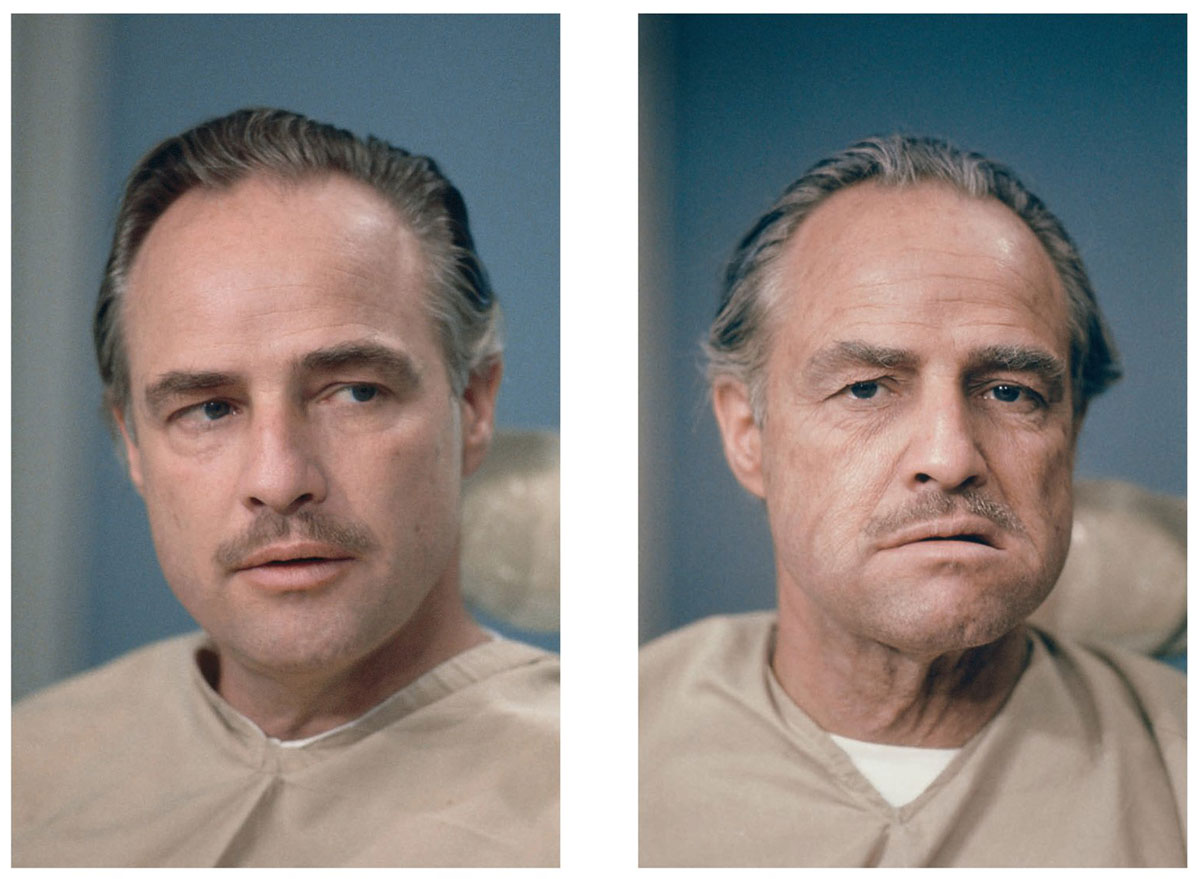

Brando slicked back his hair, streaked it, put black shoe polish under his eyes, wadded his cheeks and nostrils with tissues, held a cup of espresso and a cigar, and walked around muttering to himself. “He looked like my uncle Louie,” said Coppola, satisfied.

Back at the next executive session in New York, there was still a furious debate over whether the film should be shot in New York as an expensive period picture or in St. Louis as a cheaper, more modem piece. Coppola pushed for New York, pointing out that there was only a month left before shooting and that the cast of thirty had not been chosen, nor the 102 locations, let alone the forties props and cars bought or the actors rehearsed.

“Finally,” Coppola said, “the whole thing was more or less resolved. They decided to make it in New York. I had this little video set on the table. And I said, ‘Let me show you something.’ I turned it on. The tape started with Brando looking as he normally does. At which point, some of them got up and started to walk out. They stopped and watched, though, as he turned into an old man before their eyes.” Brando got the part.

On the set, Brando was patient and took direction well. “He can be charming, as well as brilliant,” Coppola said. “If you know what you want him to do, he can do it. He doesn’t need to be ‘motivated,’ like so many actors. You can say to him, for instance, ‘Marlon, can I have more anger, please?’ And he has his own apparatus for making these adjustments.”

It was Brando who added the touch of peeling the orange in his final scene and using the peel as fangs to get that unrehearsed frightened reaction from the three-year-old who played his grandson. And it was his choice to wear those grotesque fake fangs while having his stroke in the garden as the child sprays him. “He wanted to die like a tender monster. Not many stars would want to die in such an absurd way. He was-great to work with,” Coppola said.

The cast, by and large, shared that view. James Caan, who played the terrible-tempered Sonny Corleone, has said that Brando “was the greatest tension reliever of all. . . . The guy was fantastic. He kept all of our spirits flying high, joking around and playing dirty tricks on us.”

Caan and Brando and Robert Duvall, the Irish consigliore, had a running gag—“mooning”—throughout the filming. To “moon” means to surprise someone by abruptly sticking out your bare behind. While shooting the opening wedding scene in Staten Island (the unit was blocked from filming in Manhasset by local citizens), Duvall and Brando shouted dares at each other while 500 extras mingled in improvisational fun and drank wine. Then they both dropped their pants, amid laughs and popping flashbulbs. Somebody has some unusual Brando photos in his album.

Brando wasn’t above playing to an appreciative gallery. On the Mott Street set where he gets gunned down, a crowd gasped when he bled, slumped against a car and fell to the gutter. When the director yelled “Cut!” and Brando got up, the crowd applauded. Brando acknowledged them with a courtly bow.

He was late occasionally and missed the first day of filming, as well as the first return day after a two-week break, but there were no tantrums.

Brando’s meticulousness in working out the details of his characterization produced precisely what Coppola counted on—that here was a “man of respect,” a man who inspired awe in others. To make his aging Don believably hard of hearing, for example, Brando put plugs in his ears so he would actually have to strain to hear.

Brando’s obsession with realistic detail helped set a standard for the entire film. In the ambush of Sonny Corleone (filmed at a deserted section of Mitchel Field, where toll booths and billboards were built and an old runway served as Meadowbrook Parkway), the $100,000 scene was shot in one take. It involved the placement of 110 brass casings containing gunpowder squibs and sacks of fake blood in Caan’s clothes and others, with just blood, on his face and in his hair. When the fusillade of machine-gun bullets supposedly hit him, 200 explosive squibs in predrilled holes in his 1941 Lincoln Continental were detonated, the crew pulled invisible wires connected to the casings in his hair and on his face to make the blood spurt, and special effects man A. D. Flowers rapidly triggered the explosive charges in the clothes by tapping buttons on a console to which the victim was wired by a cable.

When the awards are given for 1972, Brando and most of the cast and crew of The Godfather are likely nominees. Theirs was a rare case of personalities and talents combining to surpass individual performances and effects.

Newsday, May 28, 1972

2 thoughts on “The Godfather: How Brando Brought Don Corleone to Life – by Joseph Gelmis”

It’s “Marlon”, not “Marion”.

Thank you for pointing that out. The article has been amended.