by Mark Seal

During the 1960s, a dirty, loaded word came into currency: Mafia. It signified one of the most terrifying forces on earth, the Italian-American faction of organized crime, and naturally the men who headed this force wanted to keep the word from being spoken, if not obliterate it altogether. When it became the basis of a best-selling book, and the book was sold to the movies, those men decided that they had to take action.

It all began in the spring of 1968, when a largely unknown writer named Mario Puzo walked into the office of Robert Evans, the head of production at Paramount Pictures. He had a big cigar and a belly to match, and the all-powerful Evans had consented to take a meeting with this nobody from New York only as a favor to a friend. Under the writer’s arm was a rumpled envelope containing 50 or 60 pages of typescript, which he desperately needed to use as collateral for cash.

“In trouble?,” Evans asked.

And how. Puzo was a gambler, into the bookies for ten grand, and perhaps his only hope of not getting his legs broken was in the envelope—a treatment for a novel about organized crime, bearing as its title the very word the underworld guys wanted to stamp out: Mafia. Though the word had been in use in its current meaning in Italy since the 19th century, it gained recognition in America in a 1951 report by the Kefauver Committee, a congressional group headed by Democratic senator Estes Kefauver, of Tennessee, created to investigate organized crime. The good news, Puzo claimed, was that the word had never before been used in a book or film title.

“I’ll give you ten G’s for it as an option against $75,000 if it becomes a book,” Evans remembers telling the writer, more out of pity than excitement. “And he looked at me and said, ‘Could you make it fifteen?’ And I said, ‘How about twelve-five?’”

Without even glancing at the pages, Evans sent them to Paramount’s business department, along with a pay order, and never expected to see Puzo, much less his cockamamy novel, again. A few months later, when Puzo called and asked, “Would I be in breach of contract if I change the name of the book?,” Evans almost laughed out loud. “I had forgotten he was even writing one.” Puzo said, “I want to call it The Godfather.”

Sitting in his Beverly Hills home, Evans clearly relishes describing the modest birth of a modern epic. Mario Puzo’s book became one of the best-selling novels of all time and later a classic movie that revolutionized filmmaking, saved Paramount Pictures, minted a new generation of movie stars, made the writer rich and famous, and sparked a war between two of the mightiest powers in America: the sharks of Hollywood and the highest echelons of the Mob.

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” a reporter says in John Ford’s towering 1962 Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. So what if Mario Puzo later contended that the meeting hadn’t taken place as Evans describes it, or if Variety editor Peter Bart, who was then Evans’s vice president in charge of creative affairs, says today that Puzo’s pages first came to him, not Evans? This was a project born in violent arguments among its creators and forged by the gun as much as the camera.

“Let’s go to bed,” Evans says, leading me through his Hollywood Regency home to his bedroom, where so many starlets have slept that, in the producer’s heyday, his housekeeper would place the name of the previous evening’s conquest beside his coffee cup on the breakfast table so that he could address her properly. Since his screening room burned down, in 2003, Evans has taken to showing films in his bedroom.

As we lie side by side on a fur coverlet, the room swells with Nino Rota’s famous score, and soon the screen fills with the face of Don Corleone on the day of his daughter’s wedding. “It’s the best picture ever made,” Evans says of the film that he claims “touched magic” and, in the process, almost destroyed him.

Smell the Spaghetti

Published in 1969, The Godfather spent 67 weeks on the New York Times best-seller list and was translated into so many languages that Puzo said he stopped keeping track. Paramount had bought a blockbuster cheap, but the studio bosses didn’t want to make the movie. Mob films didn’t play, they felt, as evidenced by their 1969 flop The Brotherhood, starring Kirk Douglas as a Sicilian gangster. Evans and Bart, however, thought they knew why: the Mob films of the past had been written, directed, and acted by “Hollywood Italians.” To make The Godfather a success—a film so authentic the audience would “smell the spaghetti,” in Evans’s words—they would need real Italian-Americans to produce, direct, and star.

But in the first of endless contradictions in the making of the film, they chose Albert “Al” Ruddy, a non-Italian, to produce. A tall, tough, gravel-voiced New Yorker, he had recently muscled a crazy idea for a comedy about a Nazi P.O.W. camp into the hit TV series Hogan’s Heroes. Whatever his artistic talent may have been, Ruddy was known for being able to get a movie made cheaply and quickly.

“I got a call on a Sunday. ‘Do you want to do The Godfather?,’” Ruddy remembers. “I thought they were kidding me, right? I said, ‘Yes, of course, I love that book’—which I had never read. They said, ‘Could you fly to New York, because Charlie Bluhdorn [chairman of Paramount’s parent company, Gulf & Western] wants to approve the director and producer.’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’ I ran down to a bookstore, got a copy of the book, and read it in an afternoon.”

In New York, Ruddy met the fire-breathing, profanity-spewing Austrian tycoon Charles Bluhdorn, the acquisition-mad empire builder who had bought Paramount in 1966. “His exact line to me is ‘What do you want to do with this movie?,’” Ruddy says.

Ruddy had carefully marked up the book with notes, but since he had heard rumors that Bluhdorn and Gulf & Western had had dealings with the Mob, he decided to go with his gut, street fighter to street fighter. “Charlie, I want to make an ice-blue, terrifying movie about the people you love,” he said. Bluhdorn’s eyebrows shot skyward and his grin grew wide. “He bangs the fucking table and runs out of the office.”

Ruddy had the job.

The plan was to make the movie down and dirty, set in the 1970s rather than a period piece, because period was expensive, and the budget for The Godfather was $2.5 million. As the book’s popularity grew, however, so did the budget (to $6 million), and so did the executives’ ambitions. Bluhdorn and Paramount’s president, Stanley Jaffe, began interviewing every possible superstar director, all of whom turned it down. Romanticizing the Mafia would be immoral, they declared.

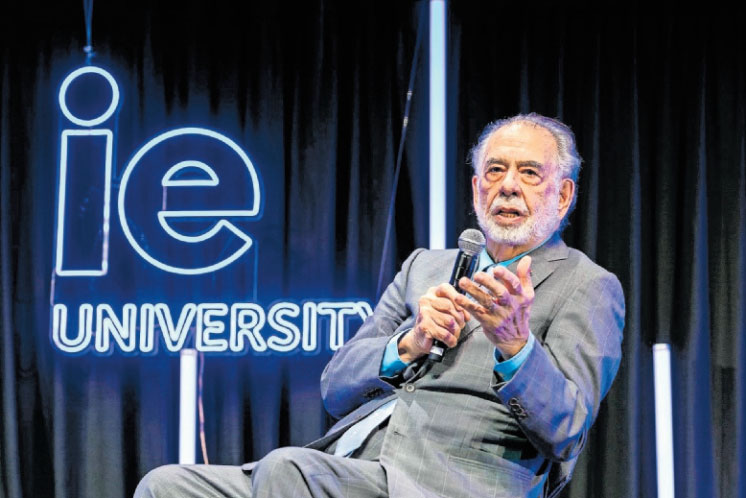

Peter Bart pushed to hire Francis Ford Coppola, a 31-year-old Italian-American who had directed a handful of films, including the musical Finian’s Rainbow, but had never had a hit. He felt that Coppola would not be expensive and would work with a small budget. Coppola passed on the project, confessing that he had tried to read Puzo’s book but, repulsed by its graphic sex scenes, had stopped at page 50. He had a problem, however: he was broke. His San Francisco–based independent film company, American Zoetrope, owed $600,000 to Warner Bros., and his partners, especially George Lucas, urged him to accept. “Go ahead, Francis,” Lucas said. “We really need the money. What have you got to lose?” Coppola went to the San Francisco library, checked out books on the Mafia, and found a deeper theme for the material. He decided it should be not a film about organized crime but a family chronicle, a metaphor for capitalism in America.

“Is he nuts?” was Evans’s reaction to Coppola’s take. But with Paramount pushing to sell the rights to the book for $1 million to Burt Lancaster, who wanted to play Don Corleone, Evans felt that he had to act fast or lose the project. So he dispatched Coppola to New York to meet with Bluhdorn.

Coppola’s presentation persuaded Bluhdorn to hire him. Immediately, he began re-writing the script with Mario Puzo, and the two Italian-Americans grew to love each other. “Puzo was an absolutely wonderful man,” says Coppola. “To sum him up, when I put a line in the script describing how to make sauce and wrote, ‘First you brown some garlic,’ he scratched that out and wrote, ‘First you fry some garlic. Gangsters don’t brown.’”

Two things quickly became apparent to Coppola: for the film to be authentic, it had to be a period piece, set in the 1940s, and it had to be filmed in New York City, the stomping ground of the Mob.

Puzo knew the Mob world extremely well, but from a distance. “I’m ashamed to admit that I wrote The Godfather entirely from research,” he said in his memoir, The Godfather Papers and Other Confessions. Ed Walters, formerly a pit boss at the Sands hotel in Las Vegas, recalls Puzo’s distinctive style of research. He would stand for hours on end at the roulette wheel, asking questions between bets. “Once we realized he wasn’t a cop, and he wasn’t some investigator,” Walters says, he and the dealers and the other pit bosses would talk to Puzo—as long as he kept betting.

“I never met a real, honest-to-god gangster,” Puzo added in his memoir. Neither had Coppola. “Mario told me to never meet them, never agree to, because they respected that and would stay away from you if they knew you didn’t want contact.”

But as word spread that The Godfather was being developed into a major motion picture, one Mafia boss rose up in defiance. While most mobsters shunned the spotlight, Joseph Colombo Sr., the short, dapper, media-savvy head at 48 of one of New York’s Five Families, brazenly stepped into it. After the F.B.I. took what he considered to be an excessive interest in his activities—which included loan-sharking, jewel heists, income-tax evasion, and control of a $10-million-a-year interstate gambling operation—he turned the tables on the bureau, charging it with harassment not only of him and his family but also of all Italian-Americans. In an outrageously bold move, he helped create the Italian-American Civil Rights League, claiming that the F.B.I.’s pursuit of the Mob was in fact persecution and a violation of civil rights. A top priority of the league’s was to eradicate “Mafia” from the English language, since Colombo contended that it had been turned into a one-word smear campaign. “Mafia? What is Mafia?” he asked a reporter in 1970. “There is not a Mafia. Am I the head of a family? Yes. My wife, and four sons and a daughter. That’s my family.”

What began with the picketing of F.B.I. offices on March 30, 1970, soon grew into a crusade with a membership of 45,000 and a $1 million war chest. An estimated quarter of a million people showed up at the league’s inaugural rally in New York City in order to put the feds and everyone else on notice. “Those who go against the league will feel [God’s] sting,” said Colombo.

The film The Godfather quickly became the league’s No. 1 enemy. “A book like The Godfather leaves one with a sickening feeling,” read a form letter the league addressed to Paramount and many elected officials, following a rally in Madison Square Garden that raised $500,000 to stop production.

“It became clear very quickly that the Mafia—and they did not call themselves the Mafia—did not want our film made,” says Al Ruddy’s assistant, Bettye McCartt. “We started getting threats.”

The Los Angeles Police Department warned Ruddy that he was being tailed. He became so concerned that he began swapping cars routinely with members of his staff to avoid recognition. One night, after he had traded his late-model sports car for McCartt’s company car, she heard the sound of gunfire outside her house on Mulholland Drive. “The kids were hysterical,” McCartt recalls. “We went outside to see that all the windows had been shot out of the sports car. It was a warning—to Al.”

On the dashboard was a note, which essentially said, Shut down the movie—or else.

Warren Beatty as Michael Corleone?

Screen-testing nevertheless commenced. From the beginning, Coppola had envisioned all of the four male actors who would eventually be cast in the leading roles, including Marlon Brando. But he had to fight Paramount’s executives for each and every one. “Francis called Robert Duvall, Al Pacino, and me,” says James Caan, “and we flew up to Zoetrope, in San Francisco,” where Coppola conducted an unofficial screen test without telling Paramount. “His wife, Eleanor, put a bowl on our heads and cut our hair, and for the price of the four corned-beef sandwiches we had at lunch he shot this 16-mm. improvisation,” Caan adds.

“My wife, Ellie, helped cut their hair, although later, when the studio felt Al Pacino was too scruffy, we brought him to a real barber and told him to give him a haircut like a college student,” says Coppola. “When the barber heard it was for the guy who might play Michael in The Godfather, he literally had a heart attack, and they had to carry him to the hospital. But, yes, we did those tests, including Diane Keaton, very inexpensively in San Francisco. But Bob Evans didn’t really go for it, so we later spent hundreds of thousands of dollars shooting practically every young actor in New York and Hollywood.”

Evans, Bluhdorn, and the other executives hated Coppola’s casting choices, especially Pacino, who they felt was far too short to play the soldier who becomes the future don. “A runt will not play Michael,” Evans told Coppola.

In his L.A. office, casting director Fred Roos runs through the long list of actors who were considered for the role of Michael Corleone: Robert Redford, Martin Sheen, Ryan O’Neal, David Carradine, Jack Nicholson, and Warren Beatty. Shortly after Roos says the name “Beatty,” the office door opens and the actor himself—whose offices Fred Roos works out of—is standing in the doorway.

“You almost got the role of Michael?,” I ask.

“There’s a story there,” says Beatty. “I was offered The Godfather before Marlon was in it. I was offered The Godfather when Danny Thomas was the leading candidate for the Godfather. And I passed. Jack [Nicholson] passed, also. And I remember something else. I was offered The Godfather to produce and direct. Charlie Bluhdorn was a fan of Bonnie and Clyde and sent me the book.… I read it. Sort of. And I said, ‘Charlie, not another gangster movie!’”

‘Francis called me one night: ‘Jimmy, they want you to come in and test.… They want you to play Michael,’” says James Caan. “That was the last thing Francis wanted, because he had it in his mind that Michael was the Sicilian-looking one and Sonny was the Americanized version. So I flew to New York, this huge studio, for these tests. There must’ve been 300 guys sitting there. Every actor you can think of was testing for this and that.” Paramount eventually spent $420,000 on screen tests, Caan says, and he tested not only for the part of Michael but also for that of consigliere Tom Hagen.

At one point, Caan was cast as Michael and Carmine Caridi as Sonny. Caridi was a Sonny straight out of Puzo’s book: a six-foot-four, black-haired Italian-American bull who came from a tough section of New York. Told that he had the part, Caridi quit the play he was appearing in and got fitted for wardrobe. When he walked down the block he had grown up on, people hanging out of windows screamed, “One of the boys made it!” “Women were coming up to me with their babies to kiss for good luck,” Caridi says. Caan recalls, “He was running around with some friends of mine, celebrating. And I said, ‘Hey, don’t do this. They’re very shaky up there, and I know what Francis wants—no disgrace to you.’ … He was going to this club and that club,” meaning clubs frequented by the boys from Caan’s old neighborhood. “They said, ‘What do you want to hang around us for?’ And he says, ‘Well, I want to get the feeling.’ They said, ‘We’ll give you the feeling. We’ll throw you out of the fucking car at 90.’”

Caridi got eliminated, but not by the Mob.

“The war over casting the family Corleone was more volatile than the war the Corleone family fought on screen,” Evans writes in his 1994 memoir, The Kid Stays in the Picture, before describing his eventual capitulation to letting Coppola cast Pacino as Michael.

“You’ve got Pacino on one condition, Francis,” he told Coppola.

“What’s that?”

“Jimmy Caan plays Sonny.”

“Carmine Caridi’s signed. He’s right for the role. Anyway, Caan’s a Jew. He’s not Italian.”

“Yeah, but he’s not six five, he’s five ten. This ain’t Mutt and Jeff. This kid Pacino’s five five, and that’s in heels.”

“I’m not using Caan.”

“I’m not using Pacino.”

“Slam went the door,” Evans wrote. “Ten minutes later, the door opened. ‘You win.’”

Evans says he had to enlist his own godfather—Sidney Korshak, the notorious Hollywood superlawyer and fixer to the Mob—to get Pacino released from his MGM contract to appear in The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, a comedy based on Jimmy Breslin’s novel about the Mob. (Robert De Niro ended up in the role.) Thus, Coppola says, the cast that he had shot on the sly in San Francisco “eventually got the parts.” And Carmine Caridi was out as Sonny.

“I don’t think I’ve gotten over it, still,” says Caridi. Coppola apparently felt so bad about it that he and Puzo wrote a role for Caridi in The Godfather: Part II. Caridi recalls, “I said, ‘Francis, I’m under indictment for some charge. I’ve got to pay my lawyer.’” Coppola asked what the lawyer’s name was and sent him a check. Caridi went on to a successful career on television. He also appeared in many other films, including The Godfather: Part III.

Along with Joe Colombo and the Mob, the producers also had to contend with Frank Sinatra during pre-production. Sinatra despised The Godfather, both as a book and as a movie, and for good reason: the character of Johnny Fontane, the drunken, whoring Mob-owned singer turned movie star who enters Puzo’s novel on page 11, sloppy drunk and fantasizing about murdering his “trampy wife when she got home,” was widely believed to have been based on Sinatra. In his desire to rise from singer to actor, Fontane also seemed to resemble Al Martino, who had performed in gangland nightclubs on both coasts and in Vegas. Phyllis McGuire, one of a famous singing-sisters trio and the girlfriend of mobster Sam Giancana, thought Fontane was a dead ringer for Martino. According to Martino, McGuire told him, “I just read a book, The Godfather. Al, Johnny Fontane is you, and I know you can play it in the movie.”

He says he contacted Al Ruddy, and—amazingly, given that Martino had never acted—Ruddy gave him the part. He got released from his contract at the Desert Inn in Las Vegas and lost what he estimates was a quarter-million dollars in nightclub-appearance fees while waiting for production to begin—only to be dropped from the cast when Coppola signed on as director.

But then he got the role back. When I ask him to explain how that happened, he says, “Well, your past has a lot to do with your future.” As we sit in a booth at Nate ’n Al, the Beverly Hills delicatessen, he tells me a story strikingly similar to Johnny Fontane’s. In 1952, when Martino’s recording of “Here in My Heart” was the No. 1 single in America, two thugs showed up at the door of his manager’s house, asking to buy his contract. Informed that it was not for sale, the men threatened the manager’s life. “And he just gave them my contract for free,” says the singer.

After Martino fired the mobsters, he received a warning never to go back East, which he ignored. He showed up to appear on the bill with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis at the 500 Club, the legendary Mob-frequented nightclub in Atlantic City, where two thugs worked him over. Then they held a promissory note for $80,000 in front of him, which they explained was “future earnings, the money we could’ve made off of you.” He signed the note and fled to England, where he stayed for six years. In 1958 he called Angelo Bruno, “the Gentle Don,” to broker his return.

Once he’d been through all that, Martino says, what was a movie director to stand in his way? He shows me a picture of himself with Puzo, Coppola, Ruddy, and some casino bosses in Vegas, all with their arms around one another, on their way to a party—complete with showgirls, “the works”—the singer says he threw at a cost of $20,000 to convince Coppola that he was the right choice for the Johnny Fontane role. When that didn’t solidify the deal, he took a course of action that could have come from the movie. “Didn’t the Don send Tom Hagen to convince [studio head] Jack Woltz that Johnny Fontane must be in the movie?” he asks. “Isn’t it similar to what I did? Woltz didn’t want Johnny, and Coppola didn’t want me. There was no horse’s head, but I had ammunition.… I had to step on some toes to get people to realize that I was in the effing movie. I went to my godfather, Russ Bufalino,” he says, referring to the East Coast crime boss.

He pulls out a scrapbook of old newspaper clippings, including one by syndicated Hollywood columnist Dick Kleiner: “Coppola, unaware of the Ruddy-Martino agreement, picked Vic Damone to be his Johnny Fontane. [Damone backed out.] The suspicion was that Damone had gotten the word from the Mafia to bow out because they had officially sanctioned Martino previously.”

Meanwhile, at Chasen’s restaurant in Los Angeles one night in 1970, Mount Sinatra erupted. The singer was seated at a banquette with his friend Jilly Rizzo when Ruddy walked in with Puzo. Like many other Italian-Americans, Puzo had grown up with two pictures on a wall in his family’s house—the Pope’s and Frank Sinatra’s. “I’m going to ask Frank for his autograph,” he said.

“Forget it, Mario. He’s suing to stop the movie,” said Ruddy.

But when Ruddy started table-hopping, a Hollywood climber, hoping to impress Sinatra, grabbed Puzo and steered him to the singer’s table. Sinatra turned purple with rage. “I ought to break your legs,” he fumed at the writer. “Did the F.B.I. help you with your book?”

“Frank is freaking out, screaming at Mario,” Ruddy recalls. Puzo later wrote that Sinatra called him “a pimp” and threatened “to beat the hell out of me.”

“I knew what Frank was up to,” Martino says. “He was trying to minimize the role. You know how much Johnny Fontane was in the book.” According to Coppola, however, “Johnny Fontane’s role was only minimized by [Martino’s] inexperience as an actor.” Martino fires back, “I was completely ostracized on the set because of Coppola. Brando was the only one who didn’t ignore me.”

Anyone but Brando

For three years Puzo had worked to write his way out of economic doom. He had a wife and five kids, and his list of lenders, aside from the bookies, included “relatives, finance companies, banks … and assorted shylocks.” Puzo found a model for his Godfather protagonist in the transcripts and videotapes of the nationally televised Kefauver hearings, later described as a “parade of over 600 gangsters, pimps, bookies, politicians and shady lawyers.” The star of the show was America’s premier crime boss, Frank Costello. With his rough and raspy voice, his ins with politicians, and his disdain for drug dealing, Costello was the clay from which Puzo began to create Don Vito Corleone.

Puzo put language he’d learned from his Italian-born mother—who raised seven children by herself—into the mouth of Don Corleone, but the face he put on him was Marlon Brando’s. “I wrote a book called The Godfather,” Puzo said in a letter to Brando. “I think you’re the only actor who can play the part with that quiet force and irony the part requires.” Brando was intrigued, because he saw the project as a story not of blood and guts but “about the corporate mind.” As he said later, “The Mafia is so American! To me, a key phrase in the story is that whenever they wanted to kill somebody it was always a matter of policy. Before pulling the trigger, they told him, ‘Just business, nothing personal.’ When I read that, [Vietnam War architects Robert] McNamara, [Lyndon] Johnson, and [Dean] Rusk flashed before my eyes.”

The studio executives wanted Laurence Olivier, Ernest Borgnine, Richard Conte, Anthony Quinn, Carlo Ponti, or Danny Thomas to play Don Corleone. Anyone but Brando, who, at 47, was perceived as poison. His recent pictures had been flops, and he was overweight, depressed, and notorious for causing overruns and making outrageous demands. will not finance brando in title role, the suits in New York cabled the filmmakers. do not respond. case closed.

But Coppola fought hard for him, and finally the executives agreed to consider Brando on three conditions: he would have to work for no money up front (Coppola later got him $50,000); put up a bond for any overruns caused by him; and—most shocking of all—submit to a screen test. Wisely, Coppola didn’t call it that when he contacted Brando. Saying that he just wanted to shoot a little footage, he arrived at the actor’s home one morning with some props and a camera.

Brando emerged from his bedroom in a kimono, with his long blond hair in a ponytail. As Coppola watched through the camera lens, Brando began a startling transformation, which he had worked out earlier in front of a mirror. In Coppola’s words, “You see him roll up his hair in a bun and blacken it with shoe polish, talking all the time about what he’s doing. You see him rolling up Kleenex and stuffing it into his mouth. He’d decided that the Godfather had been shot in the throat at one time, so he starts to speak funny. Then he takes a jacket and rolls back the collar the way these Mafia guys do.” Brando explained, “It’s the face of a bulldog: mean-looking but warm underneath.”

Coppola took the test to Bluhdorn. “When he saw it was Brando, he backed away and said, ‘No! No!’” But then he watched Brando become another person and said, “That’s amazing.” Coppola recalls, “Once he was sold on the idea, all of the other executives went along.”

The supporting roles were easier to cast. The New York actor John Cazale got the part of Corleone’s feckless, doomed second son, Fredo, after Coppola and Fred Roos saw him in an Off Broadway play. (Cazale, who later became engaged to Meryl Streep, died of cancer in 1978.) Richard Castellano, the stage and film actor, was a natural for the Don’s fat, affable lieutenant, Clemenza, and the tall, dark, warmhearted menace Tessio was immortalized by the veteran stage actor Abe Vigoda in his first U.S. film role. “I’m really not a Mafia person,” he says today. “I’m an actor who spent his life in the theater. But Francis said, ‘I want to look at the Mafia not as thugs and gangsters but like royalty in Rome.’ And he saw something in me that fit Tessio as one would look at the classics in Rome.” To get the right tone, this dignified actor of Russian descent says he “practically lived in Little Italy during the shoot.” His performance was so convincing that his future work consisted mainly of gangster and detective roles.

In mid-March 1971, Coppola gathered his actors at an Italian restaurant in Manhattan, and with the Corleones finally sitting around a dinner table together, rehearsals began. True to Coppola’s conception of the movie as a family saga, he cast many of his own family members in the film, most notably his sister, Talia Shire, as the Don’s daughter, Connie Corleone, whom Shire describes today as “a pain-in-the-ass, whiny person” in the shadow of all-powerful men. Coppola cast his father, the classically trained musician and composer Carmine Coppola, as the gun-toting mobster playing the piano as the Corleones go to the mattresses in the six-family war. Both of Coppola’s parents played extras in the pivotal shooting scene in the Italian restaurant, and his wife and two sons were extras in the baptism scene at the end. Coppola’s infant daughter, Sofia, was the baby baptized. (Nineteen years later she would play Michael and Kay’s daughter in The Godfather: Part III.)

With the actors, as in the movie, Brando served as the head of the family. He broke the ice by toasting the group with a glass of wine. “When we were young, Brando was like the godfather of actors,” says Robert Duvall. “I used to meet with Dustin Hoffman in Cromwell’s Drugstore, and if we mentioned his name once, we mentioned it 25 times in a day.” Caan adds, “The first day we met Brando everybody was in awe.”

Driving down Second Avenue after dinner, Caan and Duvall pulled up beside the car in which Brando was riding. “Come on,” Duvall said, “moon him!”

“I go, ‘Are you crazy? I don’t do that. You’re the king of that,’” says Caan. “But he says, ‘You’ve got to do this.’ So I roll my window down, and I just stick my ass out. Brando’s falling down. And we went away crying laughing. So that was the first moon of my life, to Brando, and it was on the first day we met. But Brando won the belt. We had a belt made, mighty moon champion, after he mooned 500 extras one day.”

While the actors were getting acquainted, the producers were getting familiar with the Mob. According to one account, the film’s production offices, in the Gulf & Western Building on Columbus Circle, were “dominated by a large bulletin board covered with 8-by-10 news photos of gangland slayings and mobster funerals of the 1940s and 1950s … and photographs of New York streets and nightclubs, even of furniture auctioned from the homes of famous racketeers.” As the set and costume designers got to work and the prop department began tracking down period cars, Coppola scouted locations in Little Italy.

Married to the Mob

In the meantime, according to the 2006 British documentary The Godfather and the Mob, the Italian-American Civil Rights League was strong-arming merchants and residents in Little Italy to buy league decals and put them in their windows in order to show their support, as well as their condemnation of The Godfather. Next, the league threatened to shut down the Teamsters, which included the truckers, drivers, and crew members who were essential to making the film. Twice the Gulf & Western Building was evacuated because of bomb threats. The last straw was a call to Robert Evans, who was staying at the Sherry-Netherland hotel with his wife, Ali MacGraw, and their infant son, Joshua. Evans picked up the phone and heard a voice that, as he wrote in The Kid Stays in the Picture, “made John Gotti sound like a soprano.” The message: “Take some advice. We don’t want to break your pretty face, hurt your newborn. Get the fuck outta town. Don’t shoot no movie about the family here. Got it?”

“Bob Evans calls me, a slight hint of hysteria in his voice,” Al Ruddy remembers. “He says, ‘I just got a call from this guy Joe Colombo, saying if this movie gets made there is going to be trouble.’ So Bob says, ‘I’m not producing it. Al Ruddy is.’ And Joe Colombo says, ‘When we kill a snake, we chop its fucking head off.’”

“Go see Joe Colombo,” Evans told Ruddy.

“The league was meeting at the Park Sheraton hotel, which is famous in New York because that’s where [the Murder, Inc., boss] Albert Anastasia was killed in the barbershop,” Ruddy recalls. He looked through the crowd of 50 or 60 men gathered at the hotel until he spotted Joe Colombo, “an average-looking guy, immaculately dressed—the antithesis of the cliché mobster. None of this ‘Hey, I’ll kill ya!’ They were trying to present themselves as a civil-rights organization.”

“Look, Joe, this movie will not demean the Italian-American community,” Ruddy remembers telling him. “It’s an equal-opportunity organization. We have a corrupt Irish cop, a corrupt Jewish producer. No one’s singling the Italians out for anything. You come to my office tomorrow and I’ll let you look at the script. You read it, and we’ll see if we can make a deal.”

“O.K., I’ll be there at three o’clock.”

Ruddy continues: “So next day Joe shows up with two other guys. Joe sits opposite me, one guy’s on the couch, and one guy’s sitting in the window.” Ruddy pulled out the 155-page script and gave it to the Mob boss. “He puts on his little Ben Franklin glasses, looks at it for about two minutes. ‘What does this mean—fade in?’ he asked. And I realized there was no way Joe was going to turn to page two.”

“Oh, these fucking glasses. I can’t read with them,” Colombo said, throwing the script to his lieutenant. “Here, you read it.”

“Why me?” said the lieutenant, throwing the script to the underling.

Finally, Colombo grabbed the script and slammed it on the table. “Wait a minute! Do we trust this guy?” he asked his men. Yes, they replied.

“So what the fuck do we have to read this script for?” said Colombo. He told Ruddy, “Let’s make a deal.”

Colombo wanted the word Mafia deleted from the script.

Ruddy knew that there was only a single mention in the screenplay, when Tom Hagen visits movie producer Jack Woltz at his studio in Hollywood to persuade him to give Johnny Fontane a part in his new film, and Woltz snaps, “Johnny Fontane will never get that movie! I don’t care how many dago guinea wop greaseball Mafia goombahs come out of the woodwork!”

“That’s O.K. with me, guys,” said Ruddy, and the producer and the mobsters shook hands.

There was one more thing: Colombo wanted the proceeds from the world premiere of the film to be donated to the league, as a goodwill gesture. Ruddy agreed to that as well. “I’d rather deal with a Mob guy shaking hands on a deal than a Hollywood lawyer, who, the minute you get the contract signed, is trying to figure out how to screw you,” says Ruddy. (In the end, the proceeds did not go to the league.) Two days later, Colombo called Ruddy and invited him to an impromptu press conference. “To get the word out to our people that we’re now behind the movie,” he explained.

Ruddy thought it was a great idea. He figured there might be “a couple of Italian newspapers” covering the event. Instead, he arrived at the league offices on Madison Avenue to find a large crowd: reporters from every newspaper and crews from all three television networks were present to chronicle Paramount’s making a deal with the league. “The next morning there’s a shot of me on the front page of The New York Times with organized-crime figures at a press conference,” Ruddy says. He cites the Wall Street Journal headline that day: alleged mafia chief runs aggressive drive against saying “mafia”; godfather film cuts word.

Bluhdorn went ballistic. Not only had Ruddy held a major press conference with mobsters without Bluhdorn’s consent, he had made promises and cut deals with the Mob. Bluhdorn was determined to fire Ruddy, if he didn’t kill him first. “I ran to the Gulf & Western Building, to Mr. Bluhdorn’s floor, and there’s a board-of-directors crisis meeting going on,” Ruddy says. “Gulf & Western’s stock had dropped two and a half points that morning. I walk in, and it was the most solemn group I’d ever seen in my life. Charlie Bluhdorn said, ‘You wrecked my company!’”

Ruddy was fired on the spot, but before leaving he addressed the board: “Guys, I don’t own one share of your goddamn company. I’m not interested in what happens to Gulf & Western stock. I’m interested in getting my movie made.”

It was the first day of filming—the scene where Diane Keaton and Al Pacino come out of the Fifth Avenue department store Best & Co. in the snow—and Bluhdorn shut down the set to advise Coppola and Evans to find another producer. Coppola fought him by saying, “Al Ruddy’s the only guy who can keep this movie going!”

Bluhdorn had no choice. Ruddy was back on the picture. And Little Italy sprang to life. “The next day everybody opened up their doors, and our office was filled with Italian-Americans wanting parts in the movie,” says associate producer Gray Frederickson.

Role Models

Now that the Mob had publicly blessed the movie, members began playing a role in it, not just in the extra parts a few landed but, more important, as models for the major actors. “It was like one happy family,” says Ruddy. “All these guys loved the underworld characters, and obviously the underworld guys loved Hollywood.”

Brando had created a physical look for Don Corleone, but for his brooding character he turned to Al Lettieri, who was cast as Sollozzo, the drug-dealing, double-crossing upstart. Lettieri hadn’t had to study the Mob to get into his part; one of his relatives was a member. Brando had met Lettieri while preparing for his Oscar-winning role as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront. According to Peter Manso in his biography of Brando, it was through Lettieri that he had gotten a lot of what he put into the “I could have been a contender” scene. “It was sort of based on Al’s [relative], a Mafioso who once put a gun to Al’s head, saying, ‘You’ve gotta get off smack. When you’re on dope you talk too much, and we’re going to have to kill you.’ For Marlon the story was like street literature, something to absorb.”

In preparation for The Godfather, Lettieri took Brando to his relative’s house in New Jersey for a family dinner, “to get the flavor,” says Lettieri’s ex-wife, Jan. In addition, “Francis had sent a lot of tapes from the Kefauver Committee hearings, so Brando had been hearing how these real Mafia dons talked,” remembers Fred Roos. Soon Brando had the voice of Don Corleone. “Powerful people don’t need to shout,” he later explained.

Meanwhile, the Mob boys began paying homage to the star. “Several members of the crew were in the Mafia and four or five mafiosi had minor parts,” Brando wrote in his autobiography. “When we were shooting on Mott Street in Little Italy, Joe Bufalino arrived on the set and sent two envoys to my trailer to say he wanted to meet me. One was a rat-faced man with impeccably groomed hair and a camel’s-hair coat, the other a less elegantly dressed man who was the size of an elephant and nearly tipped over the trailer when he stepped in and said, ‘Hi, Marlo [sic], you’re a great actor.’” Then Bufalino walked in regally, “complaining about how badly the U.S. government was treating him.”

“I didn’t have an answer, so I didn’t say anything,” Brando continued. “Then he changed the subject and in a raspy whisper said, ‘The word’s out you like calamari.’”

Other members of the cast became equally fascinated by the Mob. “Tom Hagen was like a Secret Service guy,” Robert Duvall says to describe his role as Don Corleone’s consigliere. “There was a guy up in Harlem who was one of the big guys up there. And a friend of mine, who had a small part in the movie, knew him. He told me how there was a guy that kind of waited on him like a high-powered gofer. You know, he’d light his cigarette and hold his chair. My friend took me to a luncheonette, where they’d run numbers,” Duvall continues. “I’d go up there and study these guys. And my friend would say, ‘Don’t stare too hard. They’ll think you’re queer.’”

James Caan had an easier time establishing the character of Sonny. “What fucking transformation?” he asks as we sit in his Beverly Hills home beneath a large framed photograph of the Corleones. “Obviously, I grew up in the neighborhood.” He adopted the strut and copied the way he’d seen gangsters always touching themselves, and he bought two-toned shoes that gave Sonny his lady-killer gait. “I didn’t have to work on an accent or anything, but I couldn’t quite get a grasp,” he says. He was stuck on the scene where Sonny interrupts the Don during the meeting about going into the drug business with Sollozzo. One night he tried to come up with a solution. “I was shaving to go to dinner or something, and for some reason I started thinking of Don Rickles. Because I knew Rickles. Somebody was watching over me and gave me this thing: being Rickles, kind of say-anything, do-anything.”

The next morning he had Sonny’s personality down cold. “Oh, are you telling me that the Tattaglias guarantee our investment?” he cracked, with a rapid-fire, Don-Rickles-meets-the-Mob bravado that elevated his character to a whole new level. Then a phrase was delivered to him straight from improvisational heaven. It popped into his mouth as he mocked Michael, after hearing his kid brother say he intended to kill Sollozzo and McCluskey, the corrupt Irish cop who had broken his jaw: “What do you think this is, the army, where you shoot ’em a mile away? You gotta get up close, like this—and bada-bing! You blow their brains all over your nice Ivy League suit.”

Bada-bing became a mantra for mobsters and aspiring mobsters. More recently, it served as the name of Tony Soprano’s strip club in The Sopranos. “‘Bada-bing? Bada-boom?’ I said that, didn’t I? Or did I just say ‘bada-bing’?” asks Caan. “It just came out of my mouth—I don’t know from where.”

Many actors hoping to be cast in the film touted their criminal connections, as opposed to any professional experience or credentials they might have. As for “made men,” or those close to them, they felt they had a right to be in the picture. “I remember Alex Rocco,” says casting director Fred Roos, referring to the actor who played Moe Greene, the Jewish casino owner loosely based on the gangster Bugsy Siegel, who gets killed at the end of the film with a bullet to the eye. “He spun a whole tale of ‘Yeah, I used to be in the Mob.’ Without being specific, he implied that he was the real deal. So many of them said, ‘I know about this world.’ I’d say, ‘How do you know?’ And they’d say, ‘I can’t tell you exactly, but I’ve been around these people.’” (Rocco says today, “I might have told him that I was a bookie, and I did some time, but I never made it to the Mob.”)

Out of this netherworld stepped Gianni Russo, the unknown who had landed the role of Carlo, Connie Corleone’s abusive husband, who sells out Sonny. The role made Russo a star, and he has milked it for all it’s worth.

I meet him in New York, at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, in front of the statue of St. Anthony, for whom he lights five candles every day for having survived polio as a child. The polio left him with “a gimp arm,” he says, which led him to selling ballpoint pens outside the Sherry-Netherland hotel on Fifth Avenue. Every day Mob boss Frank Costello walked by, and soon, Russo says, Costello was giving him a buck or two. One day the Mob boss gave him a hundred dollars and told him to meet him in the lobby of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel the next morning. “From that day on I was with him every day,” Russo says.

Silver-haired, with a blinding white smile, he’s dressed exclusively in Brioni, his shirt open to reveal a nine-carat-diamond necklace and crucifix. He tells me countless tall tales—about his famous Sicilian mobster great-grandfather, Angelo Russo; about his close connection to such Mob bosses as Carlo Gambino and John Gotti; about his bedroom acrobatics with too many famous women to count, from Marilyn Monroe to Leona Helmsley. He claims he has killed three men in self-defense, including a member of the Medellín coke cartel, who stabbed him in the belly with a broken Cristal-champagne bottle at his now defunct Gianni Russo’s State Street casino, in Vegas. He claims he has beaten 23 federal indictments and “never slept in a jail.”

When he read that they were casting unknowns in The Godfather, Russo commissioned a camera crew he was using to shoot television commercials for a chain of jewelry stores he ran in Las Vegas to film him acting out three of the major roles: Michael, Sonny, and Carlo. “So Bettye McCartt, Al Ruddy’s assistant, tells me that Ruddy loves exotic cars and Oriental women,” he says. Russo plucked the foxiest Asian showgirl from the chorus line of the Folies Bergère, decked her out in a miniskirted chauffeur’s costume, put her behind the wheel of his Bentley, and dispatched her to L.A., with instructions to put the screen test personally in Ruddy’s hand. Brando eventually ended up with the Asian showgirl, Russo says, and all he got was a letter of rejection. “Now my balls are in an uproar, because I spent thousands on this shoot,” he says.

Russo leans in so close I can smell his cologne. “I shouldn’t say this on tape, but Charlie Bluhdorn had a lot of good friends,” he says. “So I had some people call him and say, ‘You know, this guy Gianni Russo is a very close friend of ours.’”

Mobsters in Costume

Despite their détente with Joe Colombo and his league, the producers were still having trouble gaining clearance for the Staten Island compound that would serve as Don Corleone’s home. In stepped Gianni Russo, says associate producer Gray Frederickson; he talked to a few people, and suddenly the compound was available. Russo claims that none other than Joe Colombo insisted he be given a prominent role for his efforts. Russo was promised the part of Carlo if he could get through a reading convincingly. It would be an enactment of the scene where Carlo viciously belt-whips his pregnant wife, Connie. Paramount president Stanley Jaffe’s secretary stood in for Connie, but Russo couldn’t get into the scene. “It just wasn’t working,” he says.

Everyone broke for lunch. Russo was on a “wine-and-popcorn diet,” which had helped him shed 78 pounds for the part. During the two-hour break, Russo drank steadily from a gallon jug of Almaden Chablis, as he did every day, and when the filmmakers returned he was ready to rage. “I’m sorry, but I gotta get this part, so get ready,” he forewarned the secretary, and he “went crazy,” screaming and cursing and “throwing her all over the place, finally across a desk, where she landed in Bob Evans’s lap. They thought I was going to kill her.”

“Stop, stop! You’ve got the part!” one executive yelled.

With filming well under way, the part of Luca Brasi, Don Corleone’s ruthless henchman, was still not cast. “After I made the deal with the league, some of the guys used to come around,” says Ruddy. One day, one of the young dons was accompanied by his bodyguard, a six-foot-six, 320-pound behemoth named Lenny Montana. He was a world wrestling champion who moonlighted in various jobs in the Mob.

Coppola fell in love with him immediately, and he was cast as Brasi. “He used to tell us all these things, like, he was an arsonist,” says Frederickson. “He’d tie tampons on the tail of a mouse, dip it in kerosene, light it, and let the mouse run through a building. Or he’d put a candle in front of a cuckoo clock, and when the cuckoo would pop out, the candle would fall over and start a fire.”

When Bettye McCartt broke her watch, a cheap red one, Montana noticed. “He said, ‘What kind of watch would you like?,’ and I said, ‘I’d like an antique watch with diamonds on it, but I’ll get another $15 one.’ A week passes, and Lenny comes and he’s got a Kleenex in his hand wadded up, and he’s looking over his shoulder every step of the way.” He placed the wad of Kleenex on her desk. She opened it, and there was an antique diamond watch inside. “And he says, ‘The boys sent you this. But don’t wear it in Florida.’”

During the filming, the moviemakers and the Mob grew closer and closer. “Don’t forget, gang war had broken out while we were shooting,” says Al Ruddy.

In late June 1971, Coppola was directing some of the scenes in which Michael, as the new head of the Corleone family, vanquishes his rivals with hits on the leaders of all five warring families. On June 28, a few blocks away, in Columbus Circle, Joe Colombo was headlining the Unity Day rally of the Italian-American Civil Rights League before a crowd of thousands. Al Ruddy had been invited to sit on the dais beside Colombo, but he had then been advised not to appear.

At the rally, an African-American hit man posing as a press photographer lowered his camera, pulled out a gun, and blasted Joe Colombo at close range with three shots to the head. The hit man was then killed at the scene. It was the opening salvo in a Mob war reputedly unleashed by Crazy Joey Gallo, who had just been released from prison and was determined to shut up the grandstanding Joe Colombo for good. Colombo was rushed to Roosevelt Hospital, which his men immediately surrounded, fearing another attempt on the boss’s life. (He would die after spending the next seven years in a coma. As for Gallo, he was killed in retribution in 1972.)

The next day, June 29, Ruddy was at the St. Regis hotel, watching Richard Castellano fire into an elevator full of Michael Corleone’s enemies with a shotgun. “Would you believe it?,” Coppola said at the time. “Before we started working on the film, we kept saying, ‘But these Mafia guys don’t go around shooting each other anymore.’”

‘Francis and I have a perfect record; we disagreed on everything,” wrote Robert Evans in his memoir. Coppola had not only to battle Evans but also to contend with a mutinous crew, notably editor Aram Avakian, who told Evans, “The film cuts together like a Chinese jigsaw puzzle,” and encouraged him to fire the director. Coppola succeeded in firing Avakian instead. There was also an epic fight over lighting: in an era when films were over-lit, Gordon Willis shot The Godfather in shadow and darkness, initially horrifying the studio executives but creating a new standard in cinematography. “I just kept doing what I felt was visually appropriate for the movie,” says Willis. Coppola was fighting battles on all sides; his job wasn’t really secure until the executives saw the masterly scene of Michael gunning down Sollozzo and McCluskey.

Evans and Coppola’s toughest argument was over the director’s original cut, which, Coppola has said, he had repeatedly been ordered to keep at two hours and ten minutes. Evans insists he had commanded Coppola to add more texture and to hell with the length: “What studio head tells a director to make a picture longer? Only a nut like me. You shot a saga, and you turned in a trailer. Now give me a movie!” (Evans claims that the additional half-hour he coerced Coppola into adding saved the film; Coppola says he merely restored the half-hour that Evans had ordered be cut.)

Evans tells me that his obsession with The Godfather “ruined my whole life, personally.” It caused him to lose his sense of perspective as well as his wife, Ali MacGraw, after he insisted that she accept a starring role in The Getaway opposite Steve McQueen and let him focus on The Godfather. “I wanted her to go, be away, so I could work,” he says. MacGraw ended up leaving him for McQueen.

“Was it worth all of that?,” I ask him as we lie beside each other on his bed.

“So long ago, you know?” he says, staring at the screen and studying the elusive “magic” he had earlier marveled over touching, perhaps for the only time in his Hollywood career. The magic was the lucky result mainly of a series of accidents—Coppola’s vision of the perfect cast and crew; misunderstandings between the director and the executives; the strange camaraderie that grew between the moviemakers and the Mob; and a number of priceless ad-libs by actors that turned what was supposed to have been a low-budget movie into a masterpiece.

Examples: “Leave the gun,” Richard Castellano, as Clemenza, orders his henchman after they take out the traitorous Paulie Gatto in a parked car. “Take the cannoli,” he then adds in an inspired ad-lib. “Twenty, thirty grand! In small bills cash, in that little silk purse. Madon’, if this was somebody else’s wedding, sfortunato!,” Paulie Gatto, played by Johnny Martino, adds unscripted in his fluent Italian, about the opportunity for stealing at Connie Corleone’s wedding. When Al Martino, as the whimpering Johnny Fontane, cries over the role the big-shot producer won’t give him, and Brando barks “You can act like a man!” and slaps him, the slap was Brando’s spontaneous attempt to bring some expression into Al Martino’s face, according to Johnny Martino, who had rehearsed with Al (no relation) the weekend before. “Martino didn’t know whether to laugh or cry,” says James Caan.

Luca Brasi rehearsing his wedding wishes for Don Corleone as he waits outside the Don’s office is actually Lenny Montana rehearsing his lines, and his classic, stammering homage to the Don (“And I hope that their first child be a masculine child”) is actually the result of the wrestler’s blowing his lines, in a way no trained actor could ever have accomplished. “We were doing the scene in the office where Luca Brasi comes in and says, ‘Don Corleone, I am honored to be here on the day of your daughter’s wedding,’” says James Caan, and the hulking Montana froze. “Francis comes to me and says, ‘Jimmy, loosen him up or something.’ So I grabbed Lenny and said, ‘Len, you’ve got to do me a favor. Stick out your tongue, and I’m going to put a piece of tape on your tongue, and it will say “Fuck You” on it.’ And Lenny says, ‘No, Jimmy, stop. Don’t make me do this.’ And I said, ‘Lenny, you’ve got to trust me. We need to get laughs in here. Everybody’s going to sleep.’ He had a tongue like a shoebox. So I put this tape on his tongue, and I said, ‘Remember, when you say, “Don Corleone,” stick your tongue out.’ So everybody got set up, and Francis says, ‘Roll ’em.’ Boom! Lenny goes, ‘Don Corleone,’ sticks his tongue out, and ‘Fuck You.’ Everybody’s laughing. Brando was on the floor. Luca got loose. The next day, he comes in and goes, ‘Don Corleone,’ and Brando went, ‘Luca,’ sticks his tongue out, and he has ‘Fuck You, Too’ on his tongue.”

Caan’s rage as Sonny confronting the feds at his sister Connie’s wedding was pure instinct: “When I grabbed that poor extra as he took the picture, the guy must’ve had a heart attack. None of that was scripted. Then I remembered my neighborhood, where guys could do anything as long as they paid for it afterwards. I had this guy choked. Luckily, Richie [Castellano] grabbed me. Then I took out a 20, threw it on the ground, and walked off.”

All in the Family

‘The Mafia is a peculiar thing,” says Talia Shire, sitting in her Bel Air home. “It’s the underworld. It’s interesting to look on the dark side. But in this darkness there is the Vito Corleone family. Remember when Vito says, ‘There’s drugs,’ which he didn’t want to touch? He’s a decent man on the dark side, who is struggling to emerge into the light and bring his family there. That’s what makes it dramatically interesting.”

“There’s one reason that movie is successful and one reason only: it may be the greatest family movie ever made,” says Al Ruddy. “It’s a great tragedy of a man and the son he worships, the son who embodied all the hopes he had for his future. ‘I never wanted this for you, Michael.’” Ruddy has switched into a dead-on impression of Brando as the Don, pouring his heart out to his youngest son: “I thought that when it was your time that you would be the one to hold the strings. Senator Corleone. Governor Corleone.”

Ruddy sighs. “That was his dream. But what happened? The kid is put into the fucking line to save his father’s life, and he becomes a gangster, too. It’s heartbreaking.”

The film’s premiere was held in five theaters in New York. “Henry Kissinger, Teddy Kennedy—the whole world was going to show up,” says Ruddy, who got a call that day from one of the mobsters: “Hey, they won’t sell us no tickets to this thing.”

“To be honest, I don’t think they want you there,” Ruddy said.

“That’s very unfair, don’t you think?”

“What do you mean?”

“When they do a movie about the army, the generals are guests of honor, right? If they do a movie about the navy, who’s sitting up front? The admirals. You’d think we’d be guests of honor at this thing.”

Ruddy continues: “So I snuck out a print that Paramount never knew about, and I gave them a screening. There must have been a hundred limousines out front. The projectionist called me and said, ‘Mr. Ruddy, I’ve been a projectionist my whole life. No one ever gave me a thousand-dollar tip.’ That’s how much the guys loved the movie.”

They not only loved it—they adopted it as their own, employing the term Puzo invented (the Godfather) and frequently playing the movie’s haunting theme music at their weddings, baptisms, and funerals. “It made our life seem honorable,” Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, of the Gambino crime family, later told The New York Times, adding that the film spurred him on to commit 19 murders, whereas, he said, “I only did, like, one murder before I saw the movie.… I would use lines in real life like, ‘I’m gonna make you an offer you can’t refuse,’ and I would always tell people, just like in The Godfather, ‘If you have an enemy, that enemy becomes my enemy.’”

The actors would forever be identified with their roles—especially James Caan, who is constantly tested in public to see if he’ll react like trigger-tempered Sonny Corleone. “I’ve been accused so many times,” says Caan. “They called me a wiseguy. I won Italian of the Year twice in New York, and I’m not Italian.… I was denied in a country club once. Oh, yeah, the guy sat in front of the board, and he says, ‘No, no, he’s a wiseguy, been downtown. He’s a made guy.’ I thought, What? Are you out of your mind?”

The Godfather opened in New York on a rainy Wednesday. Ruddy watched it then for the first time with a general audience, sitting beside Pacino. They had both already seen the film so many times they decided to sneak out at the beginning and come back about 10 minutes from the end. “The lights come on, and it was the eeriest feeling of all time: there was not one sound,” Ruddy recalls. “No applause. The audience sat there, stunned.”

The movie opened wide across America on March 29, 1972, and became the biggest-grossing film of its time, doing more business in six months than Gone with the Wind had done in more than 30 years, and winning the 1972 Academy Award for best picture. (In 2005, 33 years later, when Ruddy got another Academy Award, for producing Million Dollar Baby, it marked one of the longest periods between Oscar wins by an individual.)

With The Godfather, the era of the $100 million blockbuster had begun, and its creator was the last to know. “I had been so conditioned to think the film was bad—too dark, too long, too boring—that I didn’t think it would have any success,” says Francis Ford Coppola. “In fact, the reason I took the job to write [a screenplay for the 1974 remake of] The Great Gatsby was because I had no money and three kids and was sure I’d need the money. I heard about the success of The Godfather from my wife, who called me while I was writing Gatsby. I wasn’t even there. Masterpiece, ha! I was not even confident it would be a mild success.”

Even today, Al Pacino is at a loss as to why the movie that made him a star connected so powerfully with audiences everywhere. “I would guess,” he tells me, “that it was a very good story, about a family, told unusually well by Mario Puzo and Francis Coppola.”

One of the most quoted lines from Puzo’s novel never made it to the screen: “A lawyer with his briefcase can steal more than a hundred men with guns.” Before his death, in 1999, Puzo said in a symposium, “I think the movie business is far more crooked than Vegas, and, I was going to say, than the Mafia.” By the time The Godfather had begun production, Mob lawyers and business operatives were walking down the hallways of Gulf & Western together. Unbeknownst to the moviemakers, Charlie Bluhdorn was even doing business with a shadowy Sicilian named Michele Sindona, a money-launderer and adviser to the Gambino and other Mob families as well as to the Vatican Bank, in Rome (elements that Coppola would use in plotting The Godfather: Part III). In 1970, the year The Godfather began production at Paramount, Bluhdorn made a deal with Sindona that resulted in the mobster’s construction and real-estate company’s owning a major share of the Paramount lot. In 1980, Sindona was convicted on 65 counts, including fraud and perjury. Four years later he was extradited to Italy and found guilty of ordering a murder. In his Milan jail cell, he swallowed—or got fed—a lethal dose of cyanide, the prescription favored by the Mob to silence stool pigeons.

The Mob and the moviemakers had been acting in unison all along.

Vanity Fair, February 4, 2009