by John Milius

I didn’t get the full impact of Apocalypse Now when I saw it at the Hollywood screenings in 1979. I had been angry at Francis Ford Coppola because I thought he was trying to hog all the press. Then I took a bunch of people to see it at the Cinerama Dome here in L.A. The place was full. There was a trailer for 1941 with John Belushi – another movie I had been involved with – and it was a very raucous audience, yelling at Belushi and generally being loud. All of a sudden Apocalypse Now came on, with the helicopters and the Doors’ “The End” playing. The theater went silent. There was never a comment, not a fucking noise in the audience, until the movie was over.

When the lights came up, I looked around and saw that people were sitting transfixed. Vietnam vets were there, too, weeping. I was stunned by how good the film was and what Francis had done. I was proud. I knew that we had accomplished something: whether it was good or bad, we had somehow kept the faith with those people.

Apocalypse Now achieved its highest aspiration: Not only was it immersed in the historical period and place – Vietnam – but it was an allegory of people facing reality and truth. The truth of life and the nature of war, of man, of civilization and of savagery. That is why the novel Heart of Darkness worked as a model. It’s a timeless story.

Apocalypse Now has now attained Citizen Kane status and is revered as one of the great films of all time. It wasn’t always that way. Critics excoriated Francis and me when it was first released. It is certainly, though, my most famous, and one of my best, efforts as a writer. When I die. they won’t say anything but. “John Milius. who wrote Apocalypse Now, died this week.”

The screenplay started when I was in USC’s film school – the West Point of Hollywood -with George Lucas. We hadn’t met Francis yet. George and I were the two ringleaders at school, making student films and winning awards. George was sort of the good boy and I was the bad boy. I lived in my car. I was an anarchist surfer, a complete, consummate rebel and an anti-intellectual of the worst kind. I was threatened with dismissal every other day. I’ve always had a problem with authority.

The specter of the Vietnam War was hanging over all our heads. I was the only one who wanted to enlist – everybody else wanted to go to Canada or get married. I figured sooner or later I was going to go. so I signed up for the Marine Air Program, but I had asthma. so I washed out. Then I had to reconfigure my life because I hadn’t planned on living past twenty-six – nobody in the Sixties planned on living very long – and I had assumed my legacy would be a smoking hole in the ground over there.

Today in filmmaking there are mainly people who want to be famous, who aren’t driven by the need to tell a story. They just want the fame. Hack then. I never thought about the potential rewards of anything I did. I didn’t think about whether I was going to be paid, whether I was going to get a new BMW or a house in Bel Air or any of that kind of shit. I had what I needed. I had my surfboard. I was fit. I had girls. I was trained. I was a weapon. I just needed a mission. I was STRAC: Strategic. Tough. Ready Around the Clock.

At USC I had a writing teacher, Mr. Irwin Blacker, who gave that mission to me. He’d tell us exotic Hollywood stories, including one about how many filmmakers had tried to do Heart of Darkness – most notably Orson Welles – but that nobody had been able to lick it. I had read the book when I was seventeen and had loved it.

So that did it. I said. Not only am I going to do my Vietnam movie. I’m going to use Heart of Darkness as an allegory because if you’re going to be passing under the skeleton of an elephant, it will be much better if that skeleton is the tail of a downed B-52. I had the ambitious idea of going to Vietnam and shooting the film there.

When George tells this story, exaggerating everything, he’ll say Milius was really insane. The truth is. they all wanted to go. Cinéma vérité had become a popular idea then with the emergence of films like Medium Cool which had been shot during the riots at the ’68 Chicago Democratic convention.

We were going to do it dirt cheap: shoot a feature film in 16 millimeter in Vietnam while the war was going on. Who knows, maybe we would have been killed. It certainly wouldn’t have been the same movie – nor would it have been as good without Francis.

Alter USC I was a young, cheap screenwriter, hanging out at American Zöetrope, Francis’s company. Then I cowrote Jeremiah Johnson, which became a hit for Robert Redford. I was hot. I got offers to fix up other screenplays. So I was now at the crossroads where I could become a rewriter or I could go off and write my own stuff, do my Apocalypse Now.

After The Green Berets it was unhip to do anything about Vietnam, because no studio wanted to touch the controversy. Yet in 1969 Warner Bros, struck a deal with American Zöetrope, and the screenplay for Apocalypse Now was part of that. I received fifteen thousand dollars for the script, and later, when the movie was finally made, another ten. That’s it. But you know, fifteen was enough. I was getting my surfboards at a discount anyway.

The title came from the buttons hippies wore that said NIRVANA NOW with a peace symbol. I made one with a tail and engine nasals, so that the symbol became a B-52, and read APOCALYPSE NOW. As a matter of fact, I put it on one of my boards.

Surfing was inevitably going to be featured in Apocalypse Now. One of the movie’s themes is that Vietnam was really a California War. By the Seventies. California culture had become the leading edge of the world, of hip youth. Not only the hippies, the guys in the Valley with their cars, the Beach Boys, the whole surfing culture, but also rock & roll. The British – the Beatles and the Rolling Stones – had faded: the real hip people were listening to the Byrds and the Doors.

I was obsessed with the Doors. It was my idea to use their music in the film. I remember hearing “Light My Fire’ while the Six Day War was going on. when Israel was trouncing the Arab armies and retaking the Wall. I always thought of the Doors in terms of war. though the bandmenibers were horrified by that connection. It just worked for me, though. Friends of mine who were in Vietnam said. “God. I was always plugged in to the Doors when there was a lot of stuff to be done.” One friend who was in a Special Forces camp said his group had put on “Light My Fire” and played it all night while being attacked.

Adults didn’t handle the Vietnam War very well. Remember, it was a war that was fought by teenagers, who hopped up their helicopters and put flame jobs on the gun pods. It became this sort of East-meets-West thing, an ancient Asian culture being assaulted by this teenage California culture.

In Apocalypse Now you’re given a view of transplanted America in that scene in the compound of expandable trailers where Playboy bunnies are putting on a show for the soldiers. The depiction conveys the enormity of importing all this incredible American culture and power. You get that even with the film’s image of cows being brought in by helicopter.

A friend of mine, who requests anonymity, was an important influence on Apocalypse Now. He did three tours of Vietnam in the Special Forces, and he told me the greatest power we had over there was that we could call from the sky either fire or a cow. We could burn a village down from the sky. or we could make a cow appear out of the air.

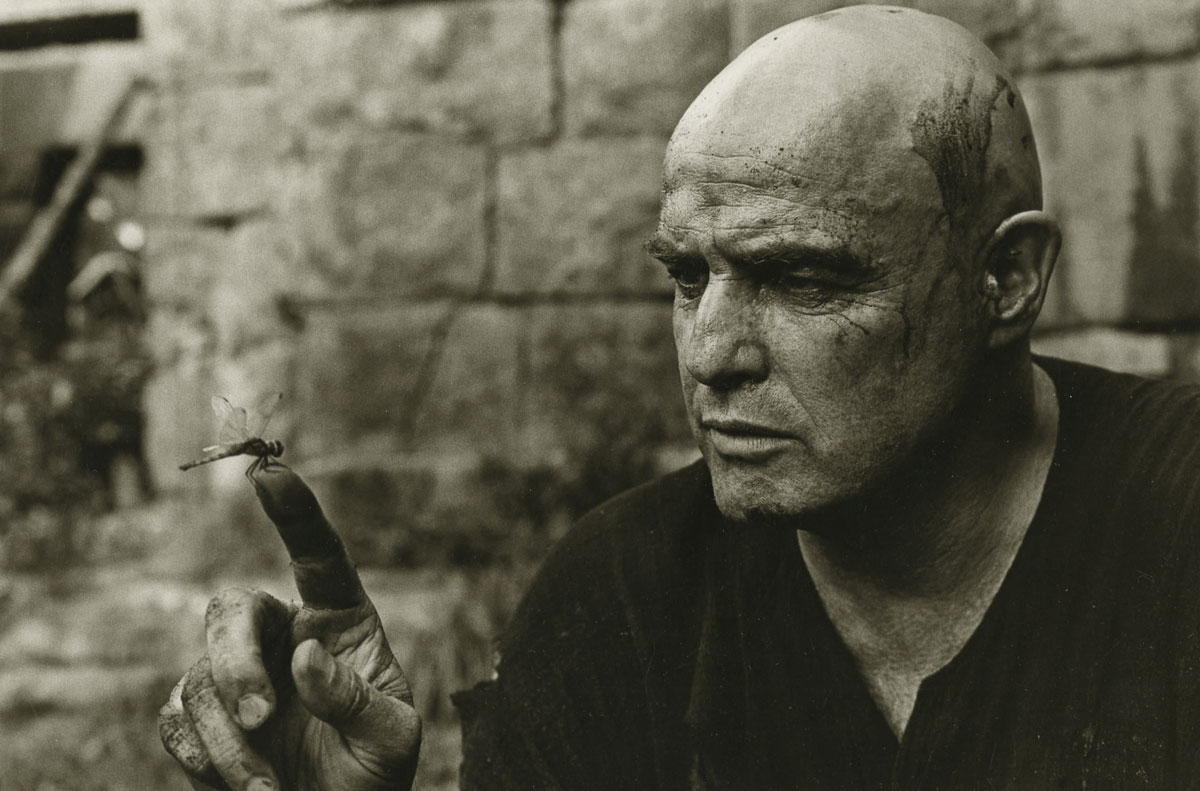

This friend was the model for Willard (played by Martin Sheen) in Apocalypse. Remember the story that Marlon Brando tells about the Communists chopping off the inoculated arms of children? It’s a true story.

My friend was a Special Forces adviser to a South Vietnamese unit when the Forces were doing civic-action programs. inoculating people from a village not too far from Saigon. Afterwards, the Viet Cong came in and chopped off all the villagers’ inoculated arms. To retaliate, the Green Beret team and the Special Forces civic-action team rounded up a bunch of known Viet Cong leaders and killed them all. My friend and the others got in trouble for it. though, because the dead had been the sources the Americans were buying intelligence from.

It’s a harrowing true story that he will have to live with for the rest of his life. Every movie that I write contains a scene like it: Somebody tells a story of an event that is more harrowing than anything that can be depicted.

I love the smell of napalm in the morning. I had been sure that that would be the first line taken out of the Apocalypse script. As leader of the First Battalion of the Ninth Cavalry Regiment. Colonel Kilgore was a wildly drawn character – straight out of Dr. Strangelove – who, I must admit. I didn’t think would ultimately work.

But Francis left the role as it had been written, and Robert Duvall is such a good actor he made it work. He made Colonel Kilgore a professional military guy who has acquired this California surfer cool and never deviates. He’s still a warrior. He’s just a warrior who surfs. He isn’t just some fucking guy who says. “Yeah man. I like to surf. I wish I could find a good point here or something.” Duvall s approach was: “That’s Charlie’s point? Yeah, well Charlie don’t surf.” You know. “Fuck Charlie! I’m going to take this point and I’m going to surf it. I’m going to surf Charlie’s waves. I’m going to fuck his women and surf his waves.”

Of all the versions there have been of the movie, there’s one that is my favorite. Francis made a tape of it for me. It ‘s three hours and five minutes long and includes some of the famous cut out French scene, more footage on the beach and more of a resolution in the end with Brando.

The version of Apocalypse most people have seen is what Francis calls the Modified Milius Ending, which hadn’t been his preferred ending. Francis’s ending shows Willard throwing down the sword, walking through everybody, getting on the boat and going down the river – that’s the end of it. No air strike. But I said. “This is Apocalypse Now. This place is evil, it has to be cauterized by lire.” Finally he came around to that idea and decided to have the air strike under the closing titles – his way of saving face but. in fact, it really worked.

Francis had the arrogance, the hubris, the ambition to make Apocalypse Now. Whenever I direct a movie. I say. “If i get sick, I’m willing to die here,” and that’s the same kind of drive Francis had. There’d be a terrible typhoon, and Francis would say. “Let’s shoot! Let’s do something! Get a camera! Let’s shoot! That’s what we came here for.” He became Kurtz.

Francis’s personality is also the one most similar to Hitler’s that I know: Hitler could convince anybody of anything, and so can Francis. Francis is my Führer. I’d follow him to hell.

Apocalypse took so much out of so many people that everyone who worked on it feels like a veteran.

When they all came back from the Philippines, the same things that happened to Vietnam Vets started happening to them. They didn’t work for a long time and suffered intense depressions, they drank and had nightmares. Everybody who worked on that movie got post-traumatic stress disorder. They had messed with the war and it had stained them.

I think filmmakers don’t have that kind of push anymore. James Cameron with his Titanic is the only example I can think of from the last twenty years. I can just hear Cameron saying something like. ’’I don’t care how much this movie costs, they’re going to have to kill me to get me oil this movie.” That’s the only way great movies get made. I’m not saying you have to spend $200 million. You can make one for $2 million, but you have to be willing to push. You have to take the samurai attitude, be willing to die in the attempt.

Today in moviemaking, there’s a pervasive fear of not being hip enough, not making the right corporate move, not having enough money. Corporate nazis have replaced individualism, dignity and ethics.

Take the Heidi Fleiss scandal. It came out that executives at a major studio were hiring Meiss’s call girls, and the corporation was paying for them. Can you believe that, having your corporation pay for your sex? The corporation telling you when and with whom and how long you could take your human pleasure? That’s lucking science fiction. Can you imagine Sam Peckinpah being given a whore and the studio saying. “We’ll pick up the tab”? He’d say: “Fuck you! I’ll pay for my own whores!”

In a way, Apocalypse Now is about a guy who decides to make his own decisions. The further he gets in his career the more he’s convinced he’s not going to listen to the crap. He says to himself. “I’m not going to fight the war they want. I’m going to win. I’m going to go out there and do what it takes to win.” And he’s willing to pay.

In the Seventies our country still retained a tinge of idealism. It was a much freer society, where the individual was important. The Vietnam War made people evaluate their lives. If you were going to he drafted, either you went and fought for your country, or you had to make the decision to fight against that. But you had to decide.

I knew one guy back then who went to every fucking riot there was and got the shit beaten out of him. 1 told him he could have gone to combat and done that and probably would have had less chance of being killed. But he fought the cops and loved doing it throwing himself into the middle of riot cops. He was a fucking warrior, just displaced.

One of my purposes in doing Apocalypse Now was to tell the story of the Vietnam War soldiers who had been treated with such incredible injustice and disrespect when they returned to America. I wanted to give them a sense of dignity and a place in history.

In order to he great, a movie has to he true. It must stay loyal to certain ideals and challenge them at the same time. Apocalypse Now challenged the inanity, the total unreasonableness of war. Everybody in the movie has gone insane, and they’re all pointing to this madman at the end of the river, who’s the one that finally tells you the truth.

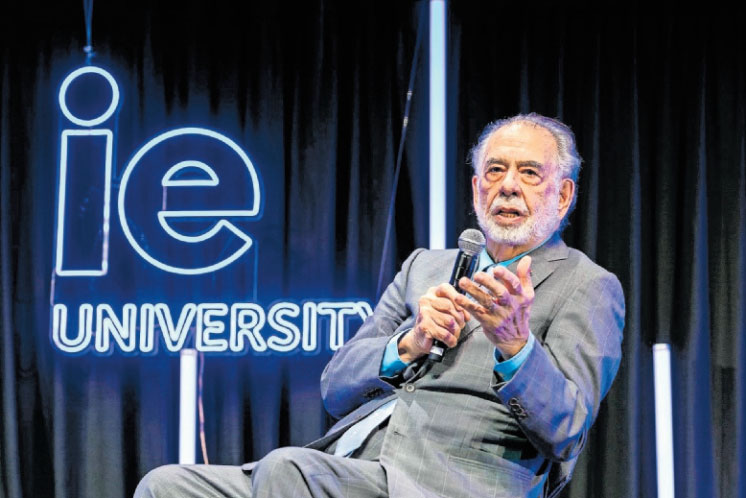

Francis and I, we still talk like old veterans. “This was a great thing we did. shouldn’t we go to war again? I mean this is what we were made for. We should go make Napoleon or do something outrageous and great and challenge Hollywood and ourselves.”

As for the Vietnam War. my opinion hasn’t changed too much since then. My feeling is that, if we were going to fight the war. we should have won. The original mistake was made by Allen Dulles and the CIA. They got us into Vietnam because they fucked up the Bay of Pigs. It was also Kennedy-family machismo Kennedy had the ability to get us out and didn’t do it. But l believe that once we were in and saying. “Okay, this is where we draw the line, we should have fought the war quickly and decisively. You don’t send young men to die in a war you don’t intend to win.

Besides Apocalypse Now and Platoon. I don’t think any of the Vietnam War films capture just how clearly ill-fated the conflict was, much as the Peloponnesian War was. It was a war that should never have happened, that became hideously immoral, and so there couldn’t he any correct political opinions about it. And yet. in a wav. every opinion was right – it was simply the war that was wrong.

Francis is a real artist. I don’t believe he’s made up his mind about the Vietnam War, so he didn’t let Kurtz have any answers. I think he wanted Apocalypse Now to be a work in progress, and every year he’d re-release it.

Is Apocalypse Now anti-Vietnam War? Nearly all the people involved in making it. from Francis on down, were against the war and held what were considered politically correct views at the time. Except for me: I wasn’t for the war. but I was for the American soldier and I wanted the film to reflect that. I wanted the grunts to be the heroes, to make a movie that they would look at and say. “This is ours.”

I believe that one of the only noble attributes of our society is its concept of the American Citizen soldier. I’m a militarist and an anarchist. But don’t expect that to make sense. As David Bowie once said when accused of contradicting himself. “Well – I’m a rock star.” What do you expect? I’m a movie director.

Meanwhile, the mystique of Apocalypse Now lives on. The Marine Corps invited me to Camp Pendleton to watch a demonstration of an aerial assault combined with an amphibious landing. As the helicopters came in, “Ride of the Valkyries” was playing over the loudspeakers. It’s become an anthem! I don’t think the United States can go to war without it.

I went to Desert Storm to photograph the war for the Marine Corps, and just after the war ended. I went out to the oil fields in Iraq. The oil was burning where the manifold had been bombed and Saddam had released the oil into the gulf, so the sky was black. They put a perimeter up and these kids were out there in the minefields in their Desert Storm outfits. Every four hundred yards there was another American solider wearing a gauze mask because of the black smoke. It was nine o’clock in the morning. It was dark. Except for the fires of hell.

A journalist friend and I walked out to the furthest guy, who was all alone in the far reaches of that hell. I said to this kid, “What unit are you with, son?”

“FIRST OF THE NINTH AIR CAV. SIR. YOU KNOW THE FIRST OF THE NINTH? HAVE YOU SEEN APOCALYPSE NOW?”

“Yeah – ‘I love the smell of napalm in the morning’!”

“YOU GOT IT, SIR!”

The soldier gave me a high five. When we were walking back, my friend asked me. “Why didn’t you tell him?”

“I think he would have shot us.”

SOURCE: Rolling Stone: The Seventies, ed. Ashley Kahn, Holly George-Warren and Shawn Dahl (Boston: Little-Brown, 1998); pp. 272-277