How “The Red Shoes” Defies Traditional Cinema with Its Fairy Tale Narrative

Powell & Pressburger balanced high & popular cinema, creating iconic films like “The Red Shoes,” a melodrama with a fairy-tale twist, blending art & emotion.

Powell & Pressburger balanced high & popular cinema, creating iconic films like “The Red Shoes,” a melodrama with a fairy-tale twist, blending art & emotion.

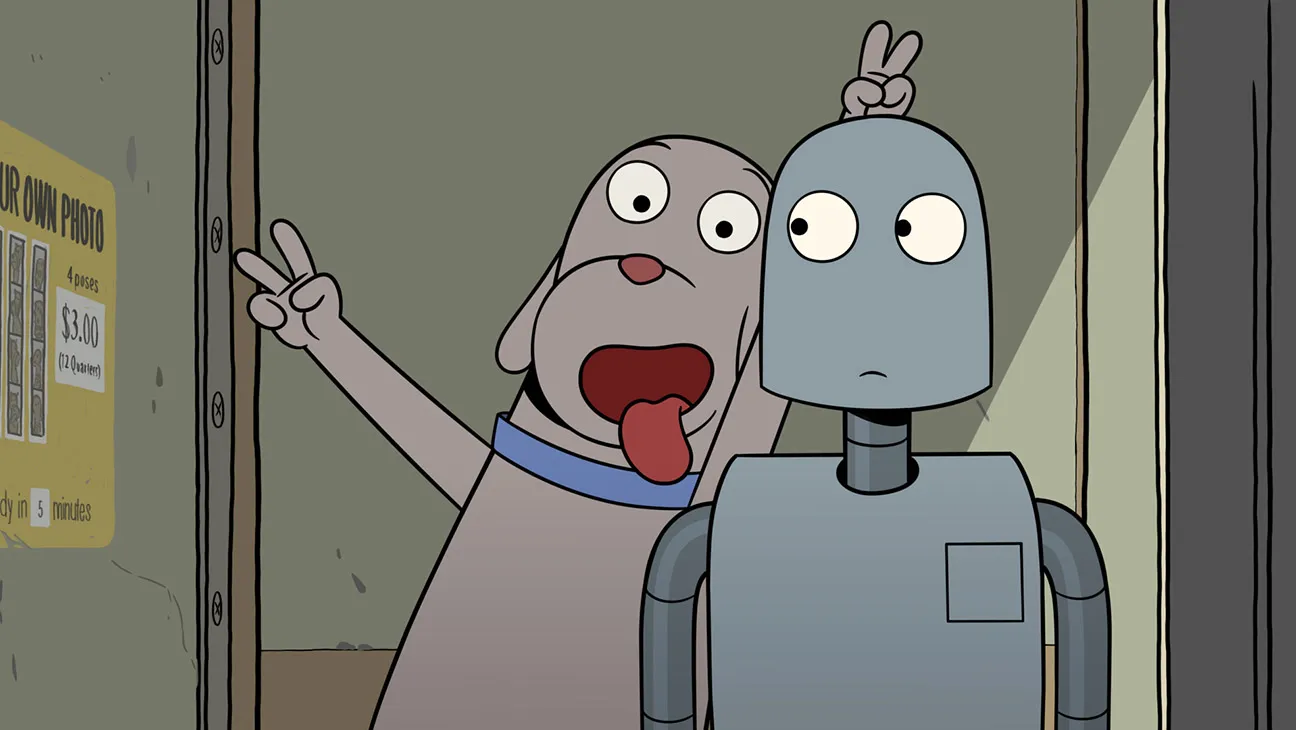

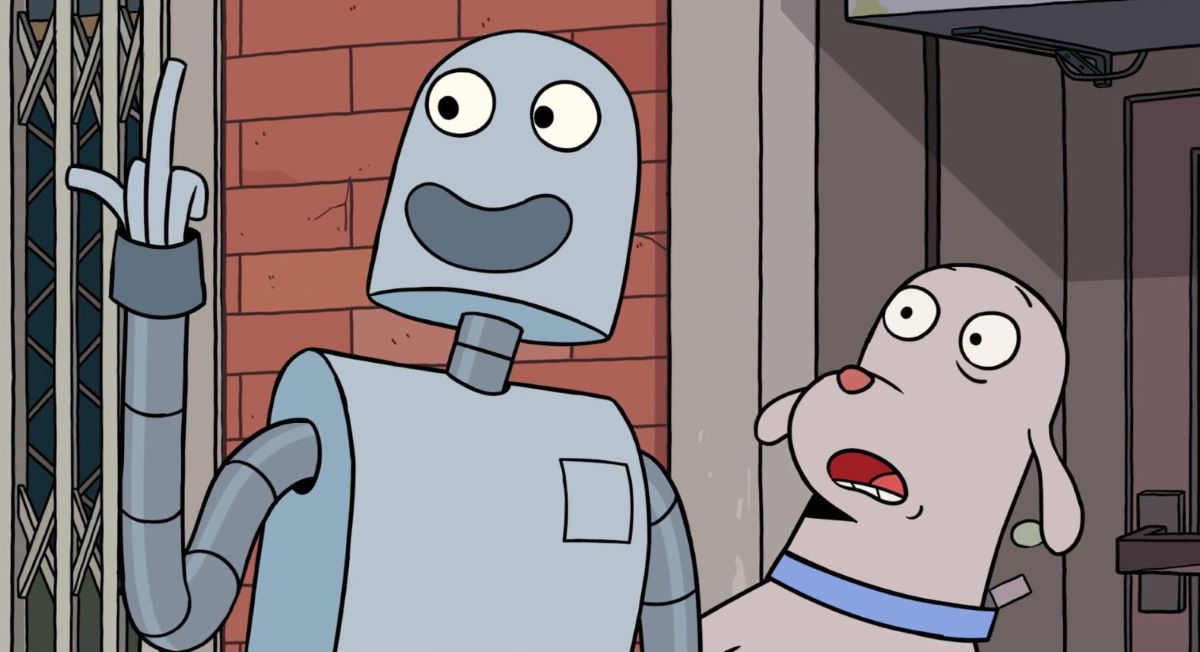

MOVIE REVIEWS Robot Dreams (2023) Directed by Pablo Berger DOG lives in Manhattan, and tired of always being alone, he builds a robot. Set to

“GoodFellas” follows Henry Hill’s journey from aspiring mobster to guilt-ridden criminal, exploring the allure and destruction of organized crime with gripping authenticity.

The wave of musical biopics has not spared Amy Winehouse: Marisa Abela avoids caricature, but the film remains superficial, teetering between hagiography and marketing.

Luca Guadagnino’s melodramatic love triangle reveals the limitless possibilities hidden within the confines of a tennis court: Zendaya’s star has never shone as brightly as it does this time.

Rosa, heart of old Marseille, balances family, work, and activism. As retirement nears and doubts rise, she finds it’s never too late for dreams.

During the world judo championships, Iranian judoka Leila and her coach Maryam receive an ultimatum from the Islamic Republic instructing Leila to fake an injury and lose the match, or else be branded a traitor to the state.

The saga of Damien begins again with the prequel: a non-trivial horror that reflects on possession from a feminist perspective.

Review: Robot Dreams skips dialogue for a beautiful story of a dog and robot’s bond. A heartwarming & unforgettable film.

Cristiane Oliveira’s ‘Até que a Música Pare’ blends loss, love, and cultural heritage into a narrative that captivates and heals.

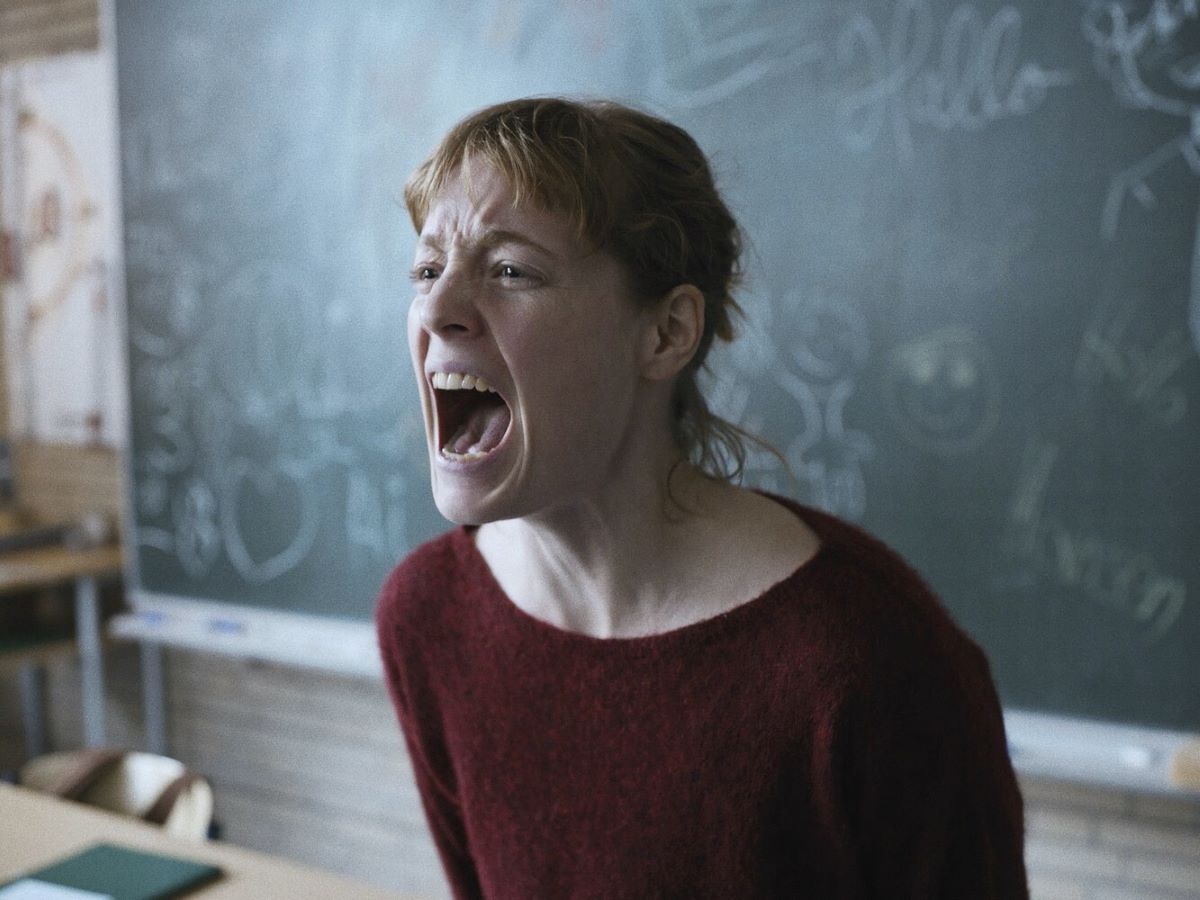

“The Teachers’ Lounge” is a thriller where an idealistic teacher clashes with suspicion & discrimination in a German school.

The film is the fifth feature in the MonsterVerse, bringing the two most iconic titans of cinema back to the big screen

Between western and drama, the film by Chilean Felipe Gálvez Haberle harshly depicts the extermination of the Ona people.

The film by Norwegian Bent Hamer remains faithful to the novel’s mood, its simple, raw, uninhibited style

While Disney is experiencing perhaps the most difficult period in its history, and while auteur animation is making more than one hit and bringing home successes and Oscars, DreamWorks reminds us that a third way is still possible.

Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman star in Todd Haynes’ “May December,” a captivating exploration of love, truth, and the price of fame.

Nikolaj Arcel returns to direct a historical film eleven years after Royal Affair, with which he won the Silver Bear in Berlin in 2012, and once again entrusts the leading role to Mads Mikkelsen.

At the beginning of Master Gardener, the blooming flowers anticipate the story that will be told but above all symbolize the circularity of life and the continuous possibility of transformation.

Masquerade blends thriller and romance with a plot of deception and love among the wealthy, set in the Hamptons. Subtle, engaging, and noir-esque.

Bruce Crouchet deems “Dune” a debacle, criticizing its pacing, adaptation, and score, resulting in a film that fails to capture the novel’s essence.

Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction mocks cancel culture & PC, with a stellar Jeffrey Wright as Monk, facing cultural wars. A must-see satire.

The “poor things” in the title of the Greek director’s film are the women subjected to an eternal, ever-changing, and renewable system of oppression and identity stripping, robbing them of agency and will.

Nolan’s “Oppenheimer” is a human, immersive film exploring the dilemma of creation, destruction, and guilt, set against a backdrop of war and scientific pursuit.

Breillat reimagines “Queen of Hearts” with a forbidden love story. Last Summer explores desire, but clunky dialogue & symbolism hold it back.

Jessica Chastain confronts a dark past when a classmate re-enters her life. Memory explores trauma, forgiveness & a glimmer of hope.

Villeneuve’s “Dune: Part Two” overwhelms with visuals but stumbles in narrative. This review explores its ambition, epic scale, and lingering imagery, questioning if it gets lost in its own grandiosity.

Andrew Haigh’s “All of Us Strangers” explores a writer’s struggle with grief, memory, and finding solace. The film is a haunting portrayal of loss and the human need for connection.

“Nashville” offers an elated cinematic adventure, mixing humor and music into a deep exploration of American culture, sans overwhelming the viewer.

The humanist sci-fi maestro Denis Villeneuve turns his gaze to jihad, letting Timothée Chalamet ride the worms: a stellar sequel

Dune 2 review: Breathtaking visuals & action, but is spectacle enough? Explore Paul Atreides’ complex journey & Villeneuve’s masterful world-building, while questioning the film’s emotional depth.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!