Emilia Pérez: A Unique Blend of Crime and Musical Drama | Review

Para-musical, gender transitions, and Mexico: Jacques Audiard brings ideas, and more, to the Competition

Para-musical, gender transitions, and Mexico: Jacques Audiard brings ideas, and more, to the Competition

Pauline Kael praises “Saturday Night Fever” for its vibrant disco scenes and John Travolta’s raw, captivating performance, capturing the romantic yearning of the seventies generation.

“The Neapolitan who lives in the psychology of the miracle,” the director who becomes Odysseus: around Parthenope, mortally wounding himself…

Coppola’s Megalopolis, a decade-long project, debuts at Cannes, facing mixed reactions. The film blends epic ambition and innovative storytelling, challenging conventional cinema.

“Era già tutto previsto”: Sorrentino’s ultimate ode to the mystery of youth and the mystery of Naples, through the life of a beautiful, indefinable, and melancholic woman. Anthropology as a perspective, for an abstract and heartbreaking film, populated by suspended ghosts. In competition for the Palme d’Or.

You are never alone in life, nothing you love can be forgotten, and memories live forever in your heart: after “A Quiet Place”, John Krasinski impresses once again

David Cronenberg takes us to the cemetery and leaves the film there: what a pity

Challengers by Guadagnino intertwines tennis and cinema, exploring deep human connections through Tashi’s relationships, revealing life’s profound truths.

A 19th-century chef and his cook’s bond unfolds through culinary perfection. Anh Hung Tran’s film uses food to explore human relationships and fulfillment.

Ali Abbasi’s “The Apprentice” at Cannes 2024 explores Trump’s rise under Roy Cohn, presenting a nuanced, judgment-free look at his formative years and America’s decline.

Kevin Costner’s “Horizon: An American Saga” premieres at Cannes, blending classic and modern western elements in an ambitious four-part series.

Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance blends body-horror and societal critique, starring Demi Moore as a star confronting her younger, more beautiful alter ego.

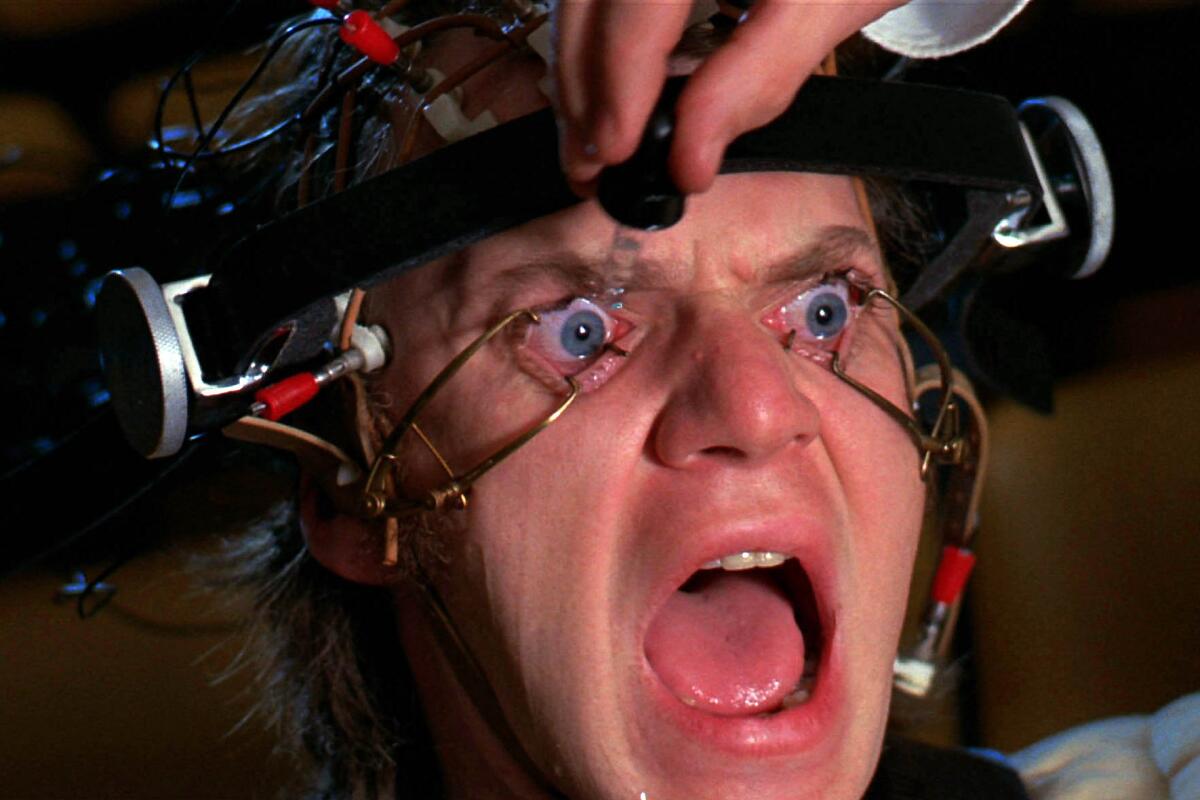

Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange blends symbolic imagery with narrative and educational elements, exploring the dichotomies of violence, morality, and aesthetics.

“Kinds of Kindness” by Lanthimos critiques modern society with absurdity and irreverence, starring Stone, Dafoe, Plemons, and Qualley. Provocative but morally shallow.

Farcical, baroque, pompous, obsessed with time: the latest grand film by Francis Ford Coppola is yet another kamikaze love letter to cinema

Luca Guadagnino’s film explores tennis as an intimate, kinetic relationship; Zendaya stars in a narrative that blends personal conflicts and professional rivalry.

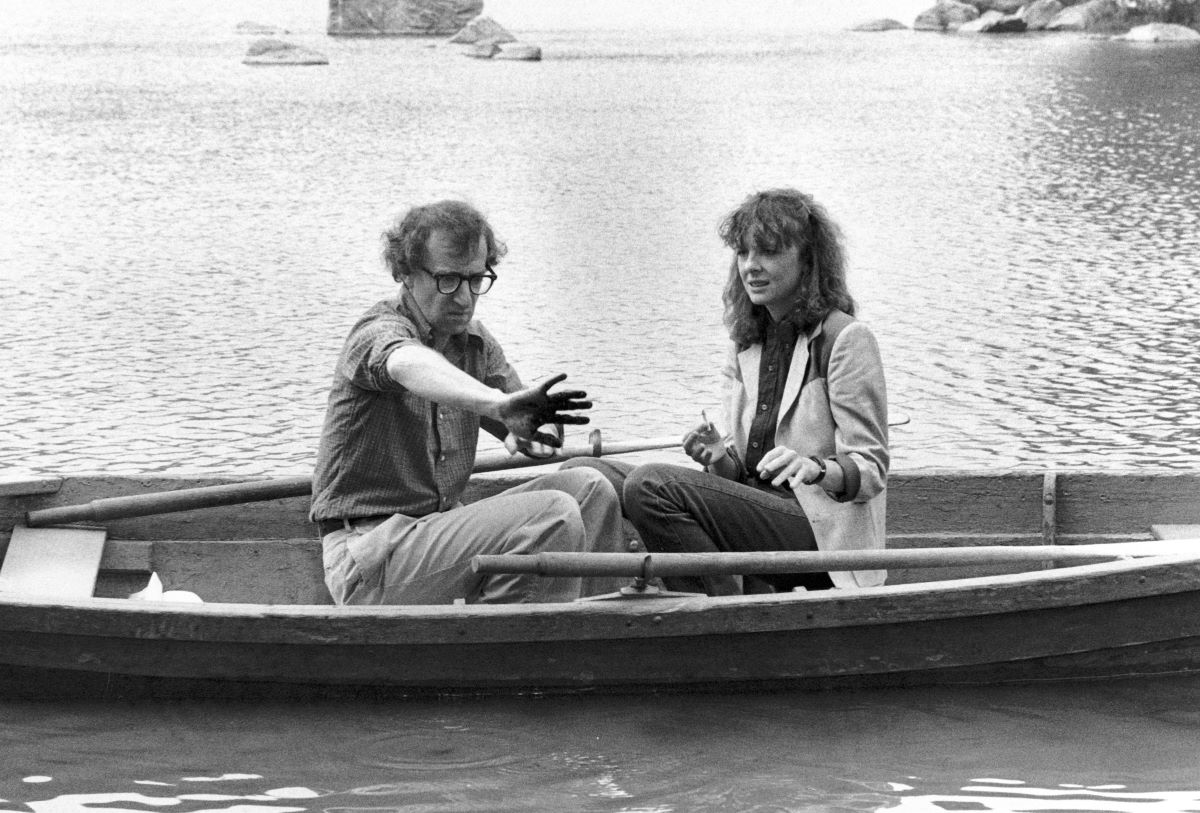

Manhattan is a faulty film, but it’s moderately amusing

Veronica Rossi revisits “Manhattan” on its 45th anniversary, highlighting its cultural impact and timeless portrayal of New York’s intellectual scene. The film blends romantic entanglements with existential satire, capturing human vulnerability amid urban chaos.

Adventure, slapstick, and sentiment blend in the sixth big-screen outing of the voracious cat: Dindal and Reynolds (The Emperor’s New Groove) are a reliable duo.

MOVIE REVIEWS Just the Two of Us (2023) French: L’Amour et les Forêts Directed by Valérie Donzelli When Blanche crosses paths with Grégoire, she believes

The portrait of the German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer, one of the most innovative and significant artists of our time, captures his life, vision, revolutionary style, and immense body of work exploring human existence and the cyclical nature of history.

Abel is a high school student struggling to focus on his final exams, while being hopelessly in love with his best friend Janka.

On April 23, 1958, Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil” was released in American theaters. It contains one of the most moving deaths and epitaphs in the history of cinema.

“Challengers” blends tennis with cinema theory, exploring relationships and visual storytelling in Luca Guadagnino’s unique style.

Based on a novel by Thomas Keneally, which in turn is based on a true story, “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” is about a rampage.

Pauline Kael explores the exuberant artistry of Abel Gance, particularly in his film Napoléon, lauding his ability to blend avant-garde filmmaking techniques with a melodramatic and romantic flair

The great Australian film “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” is a dreamlike Requiem Mass for a nation’s lost honor

How “Civil War” uses photography to challenge viewers’ reality perceptions

Alex Garland’s ‘Civil War’ offers a stark vision of a divided America.

Hoping it’s not too prophetic, the onslaught of new movie releases brings few must-sees; however, among them is “Civil War” by the ingenious Alex Garland.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!