Pauline Kael’s review of Saturday Night Fever captures the raw sensuality of John Travolta’s character, Tony, a nineteen-year-old Italian Catholic from Brooklyn. Travolta’s portrayal of Tony, with his exaggerated physicality and desperate need to dance, draws the audience into the film’s pop allure. The movie explores the financial struggles and aspirations of the seventies generation, set against the vibrant backdrop of the disco era. Kael praises director John Badham’s seamless integration of dance and narrative, highlighting the hypnotic beauty of the disco scenes. Despite the film’s occasional narrative shortcomings, such as a weak subplot involving Tony’s priest brother, Travolta’s performance as a joyful, authentic dancer elevates the movie. Kael also notes the film’s celebration of individual ambition and the desire to escape a mundane existence, encapsulated in Tony’s journey from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

* * *

Nirvana

by Pauline Kael

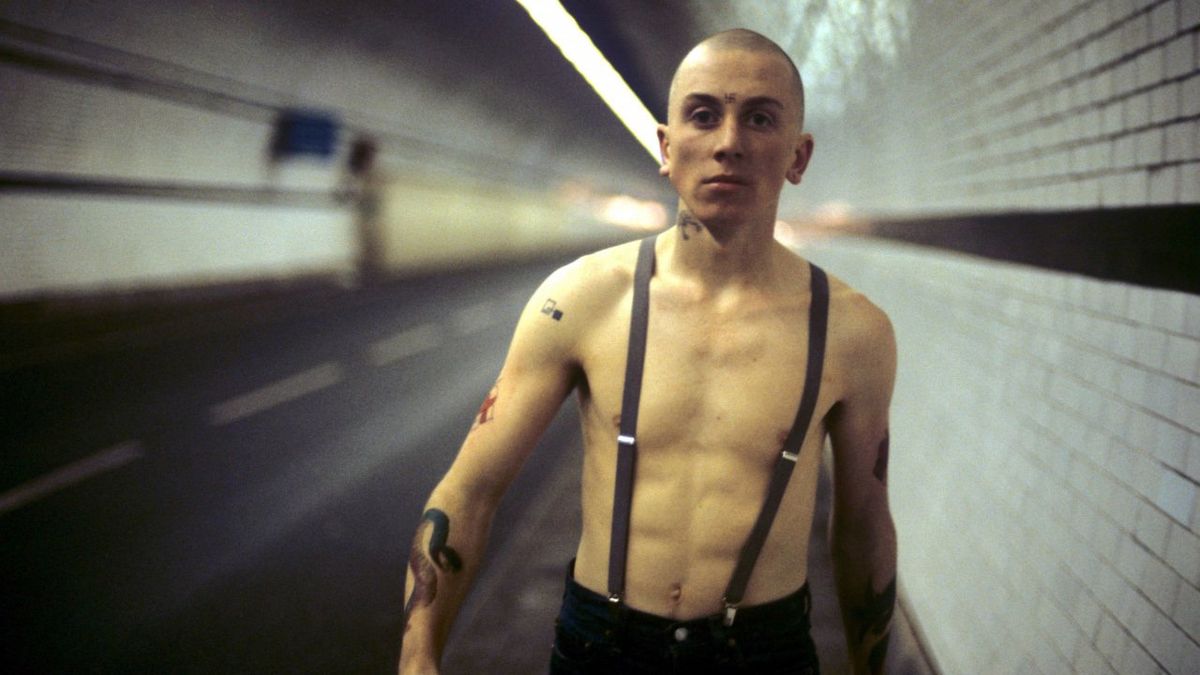

There is a thick, raw sensuality that some adolescents have which seems almost preconscious. In Saturday Night Fever, John Travolta has this rawness to such a degree that he seems naturally exaggerated: an Expressionist painter’s view of a young prole. As Tony, a nineteen-year-old Italian Catholic who works selling paint in a hardware store in Brooklyn’s Bay Ridge, he wears his heavy black hair brushed up in a blower-dried pompadour. His large, wide mouth stretches across his narrow face, and his eyes—small slits, close together—are, unexpectedly, glintingly blue and panicky. Walking down the street in his blood-red shirt, skintight pants, and platform soles, Tony moves to the rhythm of the disco music in his head. It’s his pent-up physicality—his needing to dance, his becoming himself only when he dances—that draws us into the pop rapture of this film. In his room in his parents’ cramped house, he begins the ritual of Saturday night: shaving, deodorizing, putting on gold chains with a cross and amulets and charms, selecting immaculate flashy tight clothes. The rhythm is never lost—he’s away in his dream until he’s caught in a bickering scene at the family dinner table. He leaves his home; his friends pick him up on the street, and then they’re off to the dream palace—2001 Odyssey—where Tony, who is recognized as the champion dancer, is king.

Inside the giant disco hall, the young working-class boys and girls, recent high-school graduates who plod through their jobs all week, saving up for this night, give themselves over to the music. Sharing an erotic and aesthetic fantasy, they dance the L.A. Hustle ceremonially, in patterned ranks—a mass of dancers unified by the beat, stepping together in trancelike discipline. Suggested by Nik Cohn’s June 7, 1976. New York cover story, “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” this movie has a

new subject matter: how the financially pinched seventies generation that grew up on TV attempts to find its own forms of beauty and release. The Odyssey itself (the picture was shot in the actual Bay Ridge hall) has a plastic floor and suggests a TV-commercial version of Art Deco; the scenes there are vividly romantic, with the dancers in their brightest, showiest clothes, and the lights blinking in burning neon-rainbow colors, and the percolating music of the Bee Gees. The way Saturday Night Fever has been directed and shot, we feel the languorous pull of the discotheque, and the gaudiness is transformed. These are among the most hypnotically beautiful pop dance scenes ever filmed.

The director, John Badham, who is in his thirties, has made only one previous film, The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings, but he’s well known for his work in television (The Law is probably his most impressive credit). The son of an English actress, Mary Hewitt, Badham grew up in Alabama, where his mother had her own TV talk show; his younger sister Mary played Gregory Peck’s daughter in To Kill a Mockingbird. He went on to Yale, where he, the lyricist Richard Maltby, Jr., and the composer David Shire (who worked on the score of this picture) are reported to have been fervently devoted to putting on musicals, and he has staged Saturday Night Fever with a flowing movement that makes it far more of a sustained dance film than The Turning Point. When the patrons of the Odyssey clear the floor for Tony and he does a solo, he’s a happy young rooster crowing in dance. And Badham, working with the choreographer Lester Wilson, the editor David Rawlins, and the cinematographer Ralf D. Bode, has designed this number so that it’s as smoothly seductive to us as to the onlookers. There’s no dead break between the rhythmed sequences at the Odyssey and the scenes when Tony is in hamburger joints with his friends, or at a dance studio with Stephanie (Karen Lynn Gorney), the girl who’s “different” from the other dancers, or on trips to the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge or, later, to Manhattan. These, too, have their musical beat—and are scored to songs by the Bee Gees and other groups, or to Walter Murphy’s variations on Beethoven’s Fifth, or to Shire’s “Salsation” or his Gershwin-like “Manhattan Skyline.” The film’s sustained disco beat keeps the audience in an empathic rhythm with the characters: we’re physically attuned to their fear of being trapped—of losing the beat.

It’s a straight heterosexual film, but with a feeling for the sexiness of young boys who are bursting their britches with energy and desire—who want to go—which recalls Kenneth Anger’s short film Scorpio Rising (1963). Anger celebrated the youth and sexuality and love of speed of motorcycle gangs while mocking their fetishistic trappings—the swastikas and black leather and chains that they used to simulate fearlessness. Those boys lived in a homoerotic fantasy of toughness, and their idols were James Dean and Brando, as the motorcyclist in The Wild One. The boys in

Saturday Night Fever have more traditional desires, though in a new, pop form. Their saint is Al Pacino—the boy like them who became somebody without denying who he was. When Tony looks in the mirror, it’s Pacino he wants to see, and he keeps Pacino’s picture on his wall. (He also has posters of Bruce Lee, of Farrah Fawcett-Majors, and of Sylvester Stallone and Talia Shire in Rocky.) It’s not just that Pacino is for the Bay Ridge boys what Brando was for their parents; Brando represented the rebellious antithesis of the conventional heroes of his time, while Pacino stands alone. These boys are part of the post-Watergate working-class generation with no heroes except in TV-show-biz land; they have a historical span of twenty-three weeks, with repeats at Christmas.

The script was written by Norman Wexler (Joe, Serpico, Mandingo, Drum), and it has his urban-crazy-common-man wit—the jokes that double back on the people who make them. And Badham’s kinetic style, which shows the characters’ wavering feelings and gives a lilt to their conversations (especially those between Tony and Stephanie), removes the ugliness from Wexler’s cruder scenes; the comedy is often syncopated. But Norman Wexler can’t seem to keep his mind on anything for long; you never wait more than four scenes for any issue to be resolved, and then he hops off to something else. The picture is like flash cards: it keeps announcing its themes and then replacing them. Trying for conventional family conflicts, it wanders into a deadening subplot about Tony’s older brother—a priest who has lost his vocation—which is only a cut above “All in the Family.” Trying for “action,” it brings in a gang rumble, with unwelcome echoes of West Side Story, and when one of Tony’s friends dies (for no more substantial reason than to strengthen Tony’s moral fiber), the episode throws the whole last part of the picture off course. Yet the mood, the beat, and the trance rhythm are so purely entertaining and Travolta is such an original presence that a viewer spins past these weaknesses.

John Travolta doesn’t appear to be a “natural” dancer: his dances look like worked-up Broadway routines, but he gives himself to them with a fullness and zest that make his being the teen-agers’ king utterly convincing. He commands the dance space at the Odyssey, and when the other dancers fall back to watch him it’s because he’s joyous to watch. He acts like someone who loves to dance. And, more than that, he acts like someone who loves to act. It’s getting to be a joke—another Italian-American star. Saturday Night Fever is only Travolta’s second movie (he was the Neanderthal beer-guzzling Billy in Carrie); he has become a teen and pre-teen favorite as Vinnie Barbarino in the “Welcome Back, Kotter” TV series, though, and in his one previous starring appearance, in the TV movie The Boy in the Plastic Bubble, he gave the character an abject, humiliated sensitivity that made the boy seem emotionally naked. One can read Travolta’s face and body; he has the gift of transparency. When he wants us to feel how lost and confused Tony is, we feel it. He expresses shades of emotion that aren’t set down in scripts, and he knows how to show’ us the decency and intelligence under Tony’s uncouthness. Tony’s mouth may look uneducated—pulpy, swollen-lipped, slack—but this isn’t stupidity, it’s bewilderment. Travolta gets so far inside the role he seems incapable of a false note; even the Brooklyn accent sounds unerring. At twenty-three, he’s done enough to make it apparent that there’s a broad distance between him and Tony, and that it’s an actor’s imagination that closes the gap. There’s dedication in his approach to Tony’s character; he isn’t just a good actor, he’s a generous-hearted actor.

Playing opposite him, Karen Lynn Gorney, whose facial style is as tense and hard as his is fluid and open, has a rough time at first. The story, unfortunately, introduces Stephanie in West Side Story lyrical terms as the wonderful dancer Tony wants to meet, and Gorney isn’t much of a dancer. She’s proficient—she can go through the motions—but the body is holding back. So the film overworks soft-lighting effects. It takes a while before it’s clear that Stephanie is a little climber and show-off—a Brooklyn girl who gives herself airs and talks about the important people she comes into contact with in her office job in Manhattan. Her pretensions to refinement are desperately nippy and high-pitched. (She’s reminiscent of the girl Margaret Sullavan played in The Shop Around the Corner.) She’s a phony (Tony spots that), but with a drive inside her that isn’t phony (he spots that, too). As the role is written, this girl is split into so many pieces she doesn’t come across as one person; you like her and you don’t, and back and forth. You can’t quite figure out whether it’s the character or the actress that you’re not sure about until Gorney wins you over by her small, harried, tight face and her line readings, which are sometimes miraculously edgy and ardent. The determined, troubled Stephanie, who’s taking college courses to improve herself, is an updated version of those working girls that Ginger Rogers used to play (as in Having Wonderful Time). The surprising thing is that Stephanie’s climbing isn’t put down; in a sense, the picture is a celebration of individual climbing, as a way out of a futureless squalor.

You feel great watching this picture, even if it doesn’t hold in the mind afterward, the way it would if the story had been defined. The script attempts to be faithful to the new, scrimping, dutiful teen-agers, who never knew the sixties affluence or what the counterculture was all about; for them maturity means what it traditionally meant—leaving home and trying to move ahead in the world. Once again in movies, Manhattan beckons as the magic isle of opportunity—not ironically but with the old Gershwin spirit. The awkwardness is in treating Tony as a character in passage from boyhood to maturity. The script drops the dancing, as if it were part of what Tony has to grow out of. But the dancing has functioned as a metaphor for what is driving him on to Manhattan, not what he’s leaving behind. There is a happy going-to-the promised-land, boy-gets-girl ending, yet it misplaces Tony’s soul, so it doesn’t feel as up as it should. At its best, though, Saturday Night Fever gets at something deeply romantic: the need to move, to dance, and the need to be who you’d like to be. Nirvana is the dance; when the music stops, you return to being ordinary.

The New Yorker, December 26, 1977