Andrew Haigh

All of Us Strangers

by Roberto Manassero

In London, at a grand mansion on the outskirts of the city, the screenwriter Adam encounters his neighbor Harry (Paul Mescal). After an initial reluctance, Adam begins to see more of Harry. Immersed in thoughts of his past and the memory of his deceased parents, Adam finally finds peace and love in Harry. Yet, the past weighs heavily, and Adam won’t easily shake off his ghosts.

The beauty of All of Us Strangers, and the profound sense of empathy it evokes for its protagonist Adam (a forty-year-old screenwriter from London), likely lies in the extreme narrative and visual coherence with which Andrew Haigh has translated the pages of the eponymous novel by Japanese author Taichi Yamada.

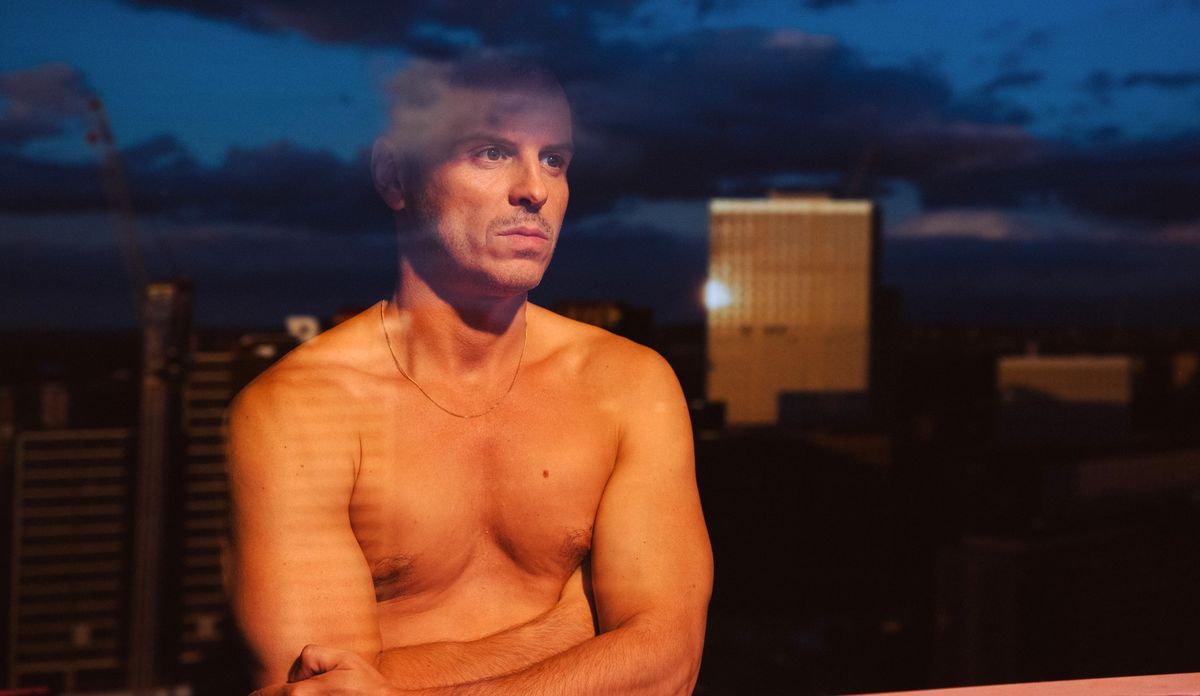

The entirety of the British director’s film is encapsulated in the mind of a man (played by Andrew Scott) who is incapable of connecting with the world; a stranger, indeed, who is first and foremost an observer: of his city, which he watches from a high and distant vantage point; of the building in which he lives alone and from which he is forced to leave in the first scene; of his own life, and particularly his past, which he experiences and simultaneously observes in sequences of gently realistic dream content.

Visually, All of Us Strangers is one of the few films that has attempted to reinterpret Bergman‘s insight into the undifferentiated dialogue between past and present, and between the living and the dead (those wonderful fluid transitions from reality to imagination and from present to past in Wild Strawberries), creating a possible physical proximity between Adam and the ghosts of his affections. The play of fire and depth of field in the first appearance of the father, who immediately presents as both a familiar presence and a disturbing one, is a directorial solution of extraordinary sensitivity: striking not only for its ability to show the ephemeral consistency of a dream, or an illusion, but for the ordinariness of the protagonist’s dream work, as if his journeys to the outskirts of London, to the house where he grew up in the ’80s and experienced the trauma that conditions his existence, were a loop from which it is impossible to escape. Just like the songs that punctuate the film, The Power of Love by Frankie Goes to Hollywood or Always on My Mind by the Pet Shop Boys.

All of Us Strangers tells the story of a fractured mind, of a man marked by pain and silence (for never having come out, for never having spoken of his parents’ death) who delves into his world and imagines impossible dialogues with himself and his dream counterpart. A lost father and mother (the astonishing Jamie Bell and Claire Foy), a lover he never had (Paul Mescal). Adam even answers the questions posed to him (how did we die?, for instance), but the answers he finds (seeing things others cannot see…) are only for himself. In the film, there is no dialogue, no way out. The protagonist’s inability to process his grief, to let others know about his homosexuality, to come to terms with an evil always rooted in the pit of his stomach, traps him in a desolate land.

However, Adam is a writer, responding to existential impasse with a creative act, but every effort to transform his story into a narrative (he’s writing a screenplay based on his memories) brings him back to square one. The encounter with his neighbor Harry, which introduces him to the pleasure of love, confidence, and meeting the other (something Haigh does marvelously well since Weekend), only serves to increase his distance from the world. When Adam tries to introduce his partner to his parents (is it dream, imagination, reality, madness?), he meets with silent gazes, a house that won’t open, a closed world in confrontation with another that cannot (or will not) communicate. Haigh’s Bergmanesque universe then becomes even Lynchian, unafraid of sliding into a potential horror of the mind.

After all, All of Us Strangers does not entertain the notion of healing or overcoming, because the reality of the day and the present, despite the dawn it opens on, is never considered. The entire film is immersed in a hypnagogic state of wakefulness, of pre-death or post-life. Pushing the envelope, it’s like a creation of Gondry, imaginative yet ultimately aphasic, and turned towards victimhood tones (something Haigh already did in Lean on Pete). If there’s a flaw, it’s in certain visual solutions (such as the overly long sequence of drug-induced stupor in a nightclub) that don’t measure up to the best moments.

Rather than a bard, as the film’s resemblance to recent similar works (Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths by Iñárritu, the novel Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders) might suggest, Adam’s world is more akin to a minor version of the planet Solaris: a place where memory materializes and fantasy attempts to amend consciousness from its mistakes. In his thoughts, Adam finds love, invents guilt and absolution, and only there, in a reality disjointed that neither writing nor imagination can interrupt, does his life manage – as the only possible act of humanity and creation – to embrace another in his arms.

Cineforum, February 29, 2024