Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) | Review by Pauline Kael

A nearly perfect work. The film is bathed in beauty, removed from the banalities of short skirts and modern-day streets and shops, and removed in time, it draws us closer.

A nearly perfect work. The film is bathed in beauty, removed from the banalities of short skirts and modern-day streets and shops, and removed in time, it draws us closer.

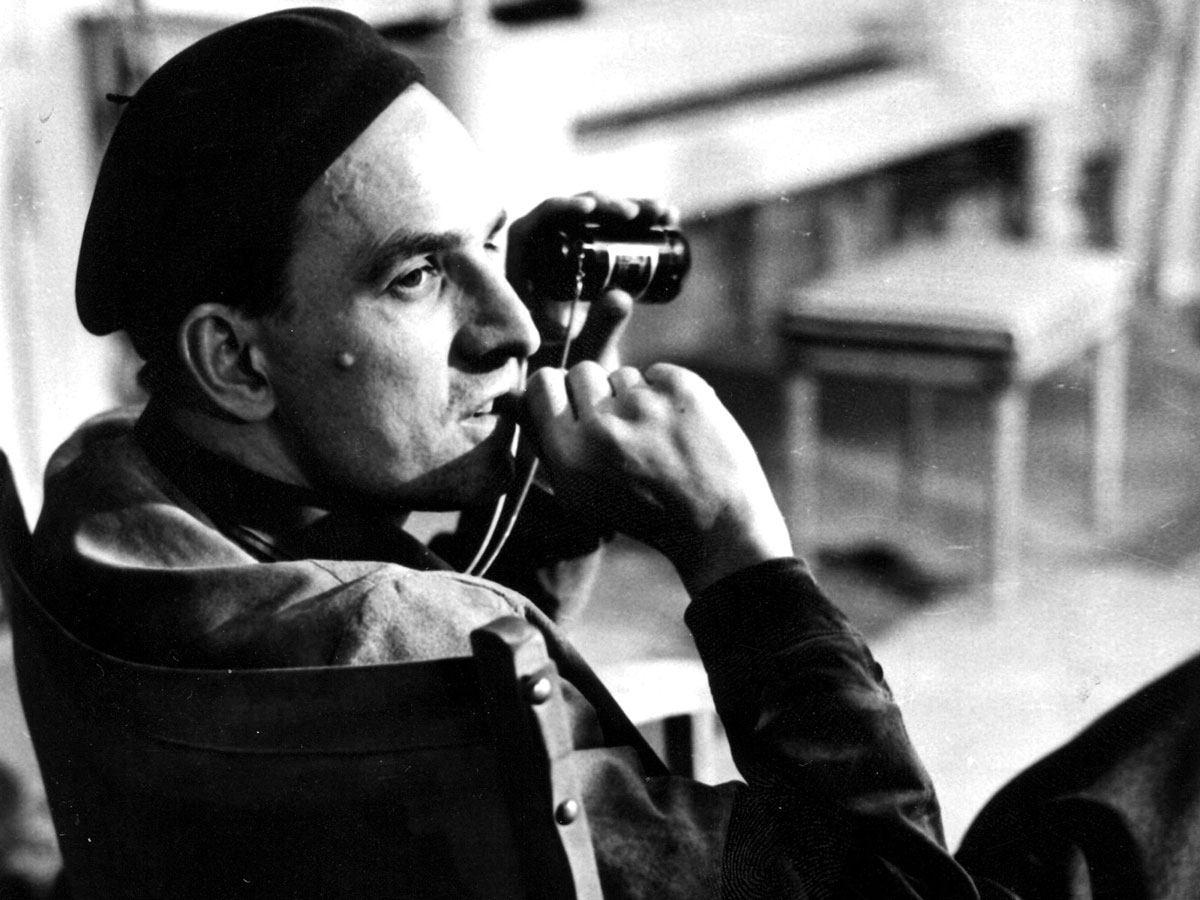

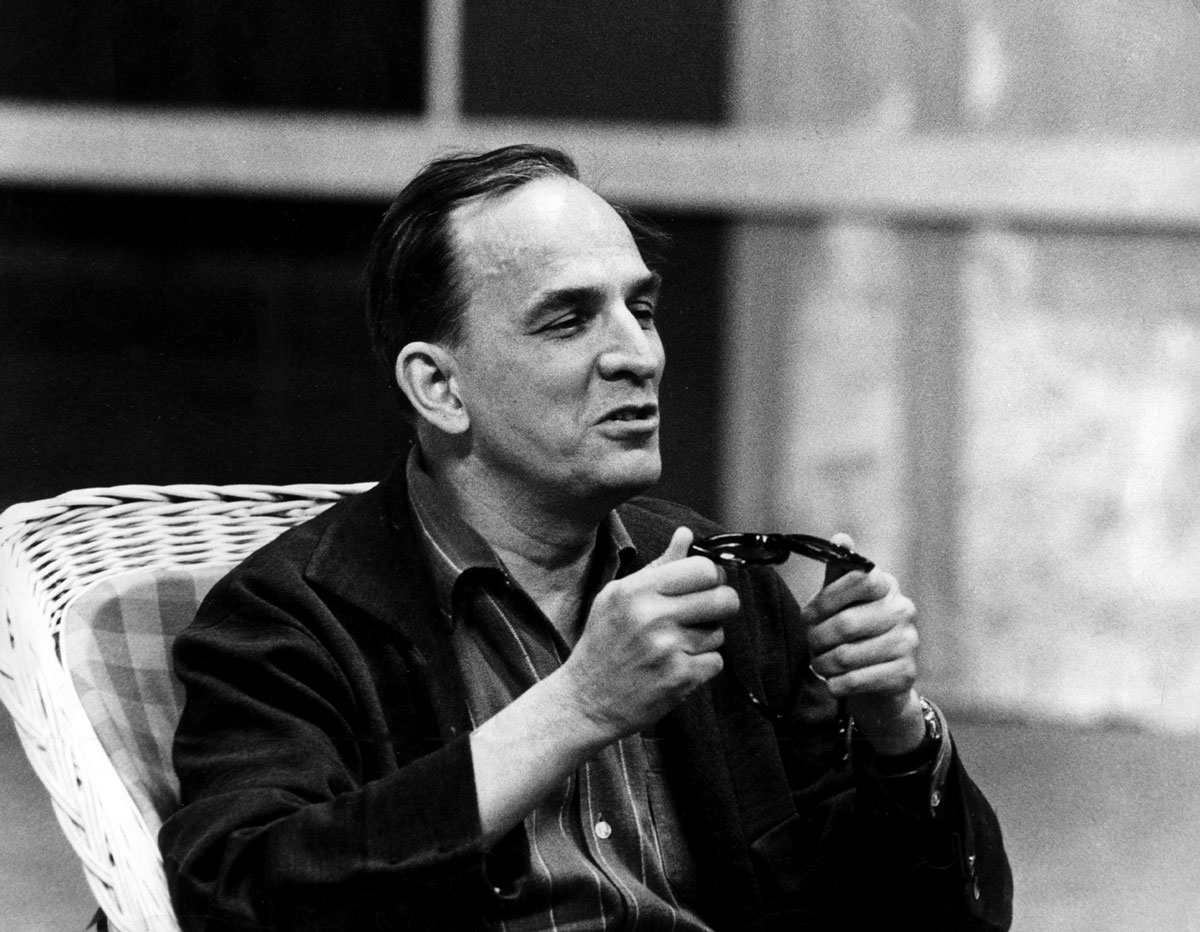

In an exclusive interview, director Ingmar Bergman tells William Wolf about his future projects and his ideas about life and art.

In teaching the films of Ingmar Bergman it has become increasingly clear to me that it is his personal vision which attracts the students. Those who do not share that vision often find Bergman unexciting; they argue that technically he has added little to the art of film making and that in the area of cinematic form he remains a borrower rather than an inventor.

After living a life marked by coldness, an aging professor is forced to confront the emptiness of his existence.

This is quite unusual, you know. We were in the elevator of the Stockholm Royal Dramatic Theatre, Bergman’s secretary (male) and I. In the elevator, going up, I was having my position made clear. You are very fortunate. Mr. Bergman is seeing no one these days while his play is in rehearsal. . .

Un documentario sulle luci e le ombre di uno dei più grandi registi di teatro e cinema

Fanny and Alexander may be Bergman’s farewell to film, but it is neither a work of pure nostalgia nor of self- pity and lamentation. It is a loving testament to and celebration of the continuity, infinite possibility, and power of art and the imagination.

Ingmar Bergman’s new comedy, As for All These Women, which opened here last night, was received coldly by Stockholm newspaper critics. “Dull” and “harmless” are two words used in reviews today.

Ingmar Bergman—the Swedish creator of The Seventh Seal—long ago abandoned his interest in the mysterious ties between God and man in favor of a broader humanism. His latest film, Cries and Whispers, confronts the realities of the human condition—man’s destiny on “the dark, dirty earth under an empty, cruel Heaven.” Now Bergman seeks his answers in the workings of the human heart alone.

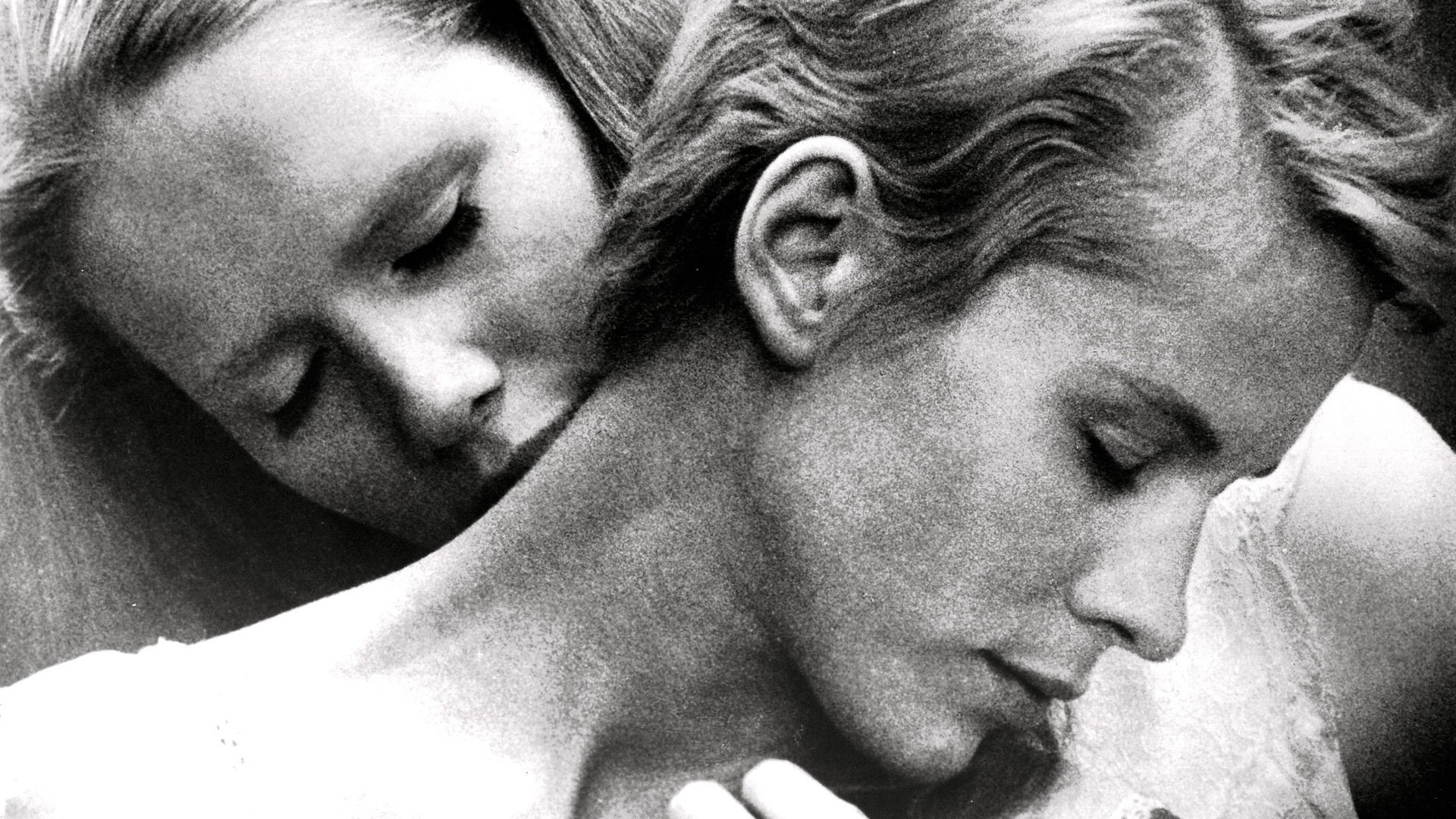

In Ingmar Bergman’s latest film, Cries and Whispers, the predominant tones are red, and from the very beginning of its production he did not hesitate to explain why this is so. He had a dream, he said, and in the dream he saw a group of women dressed in white, whispering together in a room bathed completely in red.

Bergman is not a playful dreamer, as we already know from nightmarish films like The Silence, which seems to take place in a trance. He apparently thinks in images and links them together to make a film.

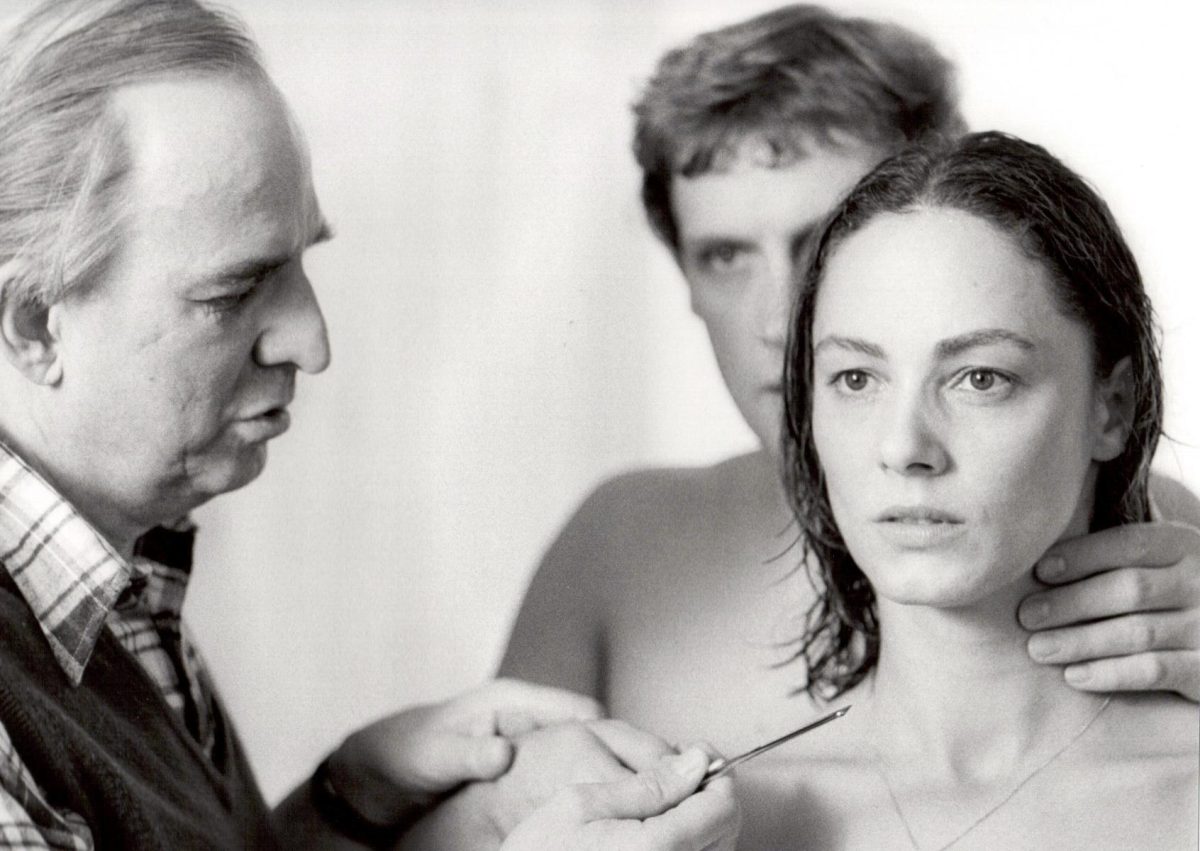

Bergman’s movies have almost always had some kind of show within the show: a ballet, a circus, a magic show, a bit of animation, many pieces of plays and even whole plays. In Persona, as in the very early Prison, Bergman involves us in the making of a movie.

Ingmar Bergman ha definito il suo ultimo film, che ha per titolo Skammen (La vergogna) una storia di gente che non ha nessuna fede, nessuna convinzione politica, che non agisce secondo canoni e regole politiche

Richard Corliss reviews Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona” for Film Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 4 (Summer, 1967)

A candid conversation with Ingmar Bergman, Sweden’s one-man new wave of cinematic sorcery. Published in Playboy n. 6, 1964

Susan Sontag reviews Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona” for Sight and Sound magazine

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!