by Birgitta Steene

In teaching the films of Ingmar Bergman it has become increasingly clear to me that it is his personal vision which attracts the students. Those who do not share that vision often find Bergman unexciting; they argue that technically he has added little to the art of film making and that in the area of cinematic form he remains a borrower rather than an inventor. They take delight in pointing out Bergman s contrived tracking-and-stop shots (vide: opening Karin-Minus sequence in Through a Glass Darkly), reminiscent of the early run-of-the-mill western; they see little value in the attic sequence in The Magician because it is ‘all Hitchcock’; and they resent the Godard-imitated interviews of the actors in The Passion.

My own interest in Bergman is neither on the “gut level” of identification nor on the technical level. Rather, it is shamelessly literary. It is so, in spite of Bergman’s own objections to analogies between film and literature. But then Bergman’s objections are rather special, based as they are on his contention that literature is an intellectual art form. Or as he states in an early essay:

Film has nothing to do with literature; the character and substance of the two art forms are usually in conflict. This probably has something to do with the receptive processes of the mind. The written word is read and assimilated by a conscious act of the will in alliance with the intellect.1

Like many of his critics Bergman also tends to confuse the term literary with verbal, a word that is anathema among most film people as it implies that language is made to carry the real message of a film rather than assist the cinematic image or sequence. But we can of course define the term “literary” in a much broader sense as certain modes of expression pertaining to an art form that may use narrative as its basis (novel); or character conflict (drama); or sound, rhythm, and metaphor (certain types of poetry). Bergman certainly transfers such literary formal patterns to the screen.

In the early stages of his career he tends, however, to rely too much on literary techniques: the Knight’s confession in church in The Seventh Seal is staged like a dramatic soliloquy; the linearity and narrative logic of Professor Borg’s oscillation between dreamworld and reality in Wild Strawberries (“I don’t know how it happened, but the day’s clear reality flowed into dreamlike images . . .”) make the visual changes—the dissolves—quite superfluous. But in later films—beginning with Through a Glass Darkly— Bergman attempts to translate literary techniques into cinematic terms, a process that can be studied by comparing the published screenplay version of a film with the finished product. Thus in The Silence, the first Bergman film to proceed almost totally from the visual, the opening passage in the screenplay relies on a whole series of descriptions of tanks, guns, armored cars, soldiers to suggest an atmosphere of war, but the film version reduces all of these to one central image: the tanks, first seen as streaks of monstrous phallic objects racing past Johan’s eyes; then, in a later sequence, reappearing as a lonely tank, grotesque in its movement and sound, passing by the hotel just after Ester, the sick sister, has nearly suffocated to death. This strictly imagistic technique—making the visual object seem significant —may not always be entirely successful: I find the lonely tank too much of a manipulated cinematic symbol. But it underscores a trend in Bergman’s production away from verbalization of meaning.

To a great extent Bergman’s films from the fifties—The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, The Magician, Smiles of a Summer Night, The Virgin Spring—do start from the written text, from a dialogue meant to convey both thematic meaning and emotional tension. When Professor Borg in Wild Strawberries looks into the microscope in one of the dream sequences and sees nothing but his own eye, we are told this. At the end of the same examination sequence we are given a neat verbal summing-up of Borg’s state of alienation; from a visual point of view the sequence has added nothing to our understanding of Borg. Similarly, in The Magician, the attic confrontation between Vogler and Dr. Vergerus, the rationalist, tends to be little more than a cinematic tour-de-force, revealing nothing about the two characters that we do not already know: their attitudes have been most explicitly stated in their first encounter in Consul Egerman’s living-room.

In the fifties, then, Bergman seems to be building up his sequences around a series of verbal episodes or encounters. But at the same time, he appears to be quite aware of his own shortcomings as a writer, and he tries to compensate for this by juxtaposing or reinforcing verbalized sequences with scenes of visual exaggeration. The results are often carefully planned contrasts of shots, executed in spooky darkness or suffused with romantic light; surroundings and weather are used as Stimmungsmalerei, as visualizations of a mood. In moments of peace and harmony the scenery will be filled with a mystical beauty and rays of sunshine will be filtering through the delicate branches of birch trees; while in moments of impending doom dark clouds will pass over the moon, black ravens will fill the sky, ominous trees in a night-time forest will cast their foreboding shadows over the screen; and, at worst, the sound track will play some highly dramatic music. Such externalizations of feelings of peacefulness or terror, where the landscape serves as the artist’s tool, might be called a form of film Gothicism. It is often coupled with a certain remoteness in Bergman to his characters, and has thus laid the foundation of the most common charge leveled against him: his lack of human warmth. True enough, several of the “Gothic” films are not only removed from the present and set in historical time but the camera is frequently placed at some distance from the main characters, so that they form part of a larger, often quite conceptualized or symbolic framework.

Most of Bergman’s films fall back on a prototypal literary form: that of a journey or quest. In The Seventh Seal a crusader returns from the Holy Land; in Wild Strawberries a professor sets out on a journey through Sweden; in The Naked Night we follow the itinerary of a group of circus people; in The Magician a charlatan travels towards the King’s palace, performing his tricks to a bourgeois audience: in The Virgin Spring a young girl rides with candle offerings to church. If we compare the journeys in the Gothic films to the travels or suggestion of travels in the later, so-called chamber films2 of the sixties we find that traveling becomes much more claustrophobic and frustrating and is, in fact, almost completely internalized. It is as though the later films emanate from the state of mind of Professor Borg during his nightmarish dreams in Wild Strawberries.

ASCETIC CLOSE-UPS

From a literary-formal point of view Bergman moves from an epic pattern and the tangible reality of the Bildungsroman to the world of the stream-of-consciousness novel. From a thematic point of view this implies a much more direct confrontation by Bergman with his personal vision; and from the point of view of cinematic style it leads to a shift from Gothicism to ever greater visual asceticism. Even when Bergman uses color in The Passion, there is no gaudiness, no lushness about it but, rather, a bleakness that reinforces the mood of sterility even more than did the black and white of earlier films.

But perhaps the most crucial change that occurs in Bergman’s film making in the early sixties is not his discarding of the historical milieu, the flashbacks, the physical travels, the broad perspectives, but his approach to the human figures—with a special emphasis on the close-up. Many of the chamber films are shot on the barren island of Faro in the Baltic. But the island landscape is no longer likely to overshadow the individual characters nor is it made to carry the full symbolic weight of the films. Now the emphasis is on the human face, an approach that began to crystallize for Bergman while he was shooting Through a Glass Darkly in 1960-61:

The solutions I seek are of three kinds: technical, formal, and esthetic; but my goal shall always be to come closer and closer to the people in the story. In Through a Glass Darkly I found, by concentrating on only four people, a new and exciting experience and, I believe, a new direction for myself.3

There are, alas, Gothic remnants in Bergman’s use of the landscape in Through a Glass Darkly. In fact, the film is interesting in that it shows us a Bergman who has not yet learnt to deal, in completely successful cinematic terms, with a Gothic psychic condition (madness)—as he does later on in The Hour of the Wolf. Nervously, or by sheer habit, he offers us his conventional Gothic montages early in the film: the sun setting “into opaque masses of cloud”; a thunderstorm brewing on the horizon; excessive dark ripples on the water; blinding light on Karin s face. The specter-looking hull of the ship where Karin seduces Minus has the same overly dramatic quality about it, with the result that when Karin s illness finally culminates in the spider-God sequence in the attic, Bergman has used up all his effects—except one: a close-up of Karin’s face in which the camera becomes Karin’s eyes and dollies up to the undulating, rippled pattern on the wallpaper. But the sequence would probably have had a greater impact had we not seen the ripples on the ocean earlier in the film: an interesting visual parallel perhaps, but also a piece of Gothic symbolism which robs the attic sequence of its full human potential.

That Bergman was becoming aware of a need to downplay the symbolic quality of his landscapes is, however, brought out by a statement made in the early 1960’s:

Our work in films must begin with the human face. We can certainly become completely absorbed in the esthetics of montage; we can bring objects and still life into a wonderful rhythm; we can make nature studies of astounding beauty, but the approach to the human face is without doubt the hallmark and distinguishing feature of the film medium.4

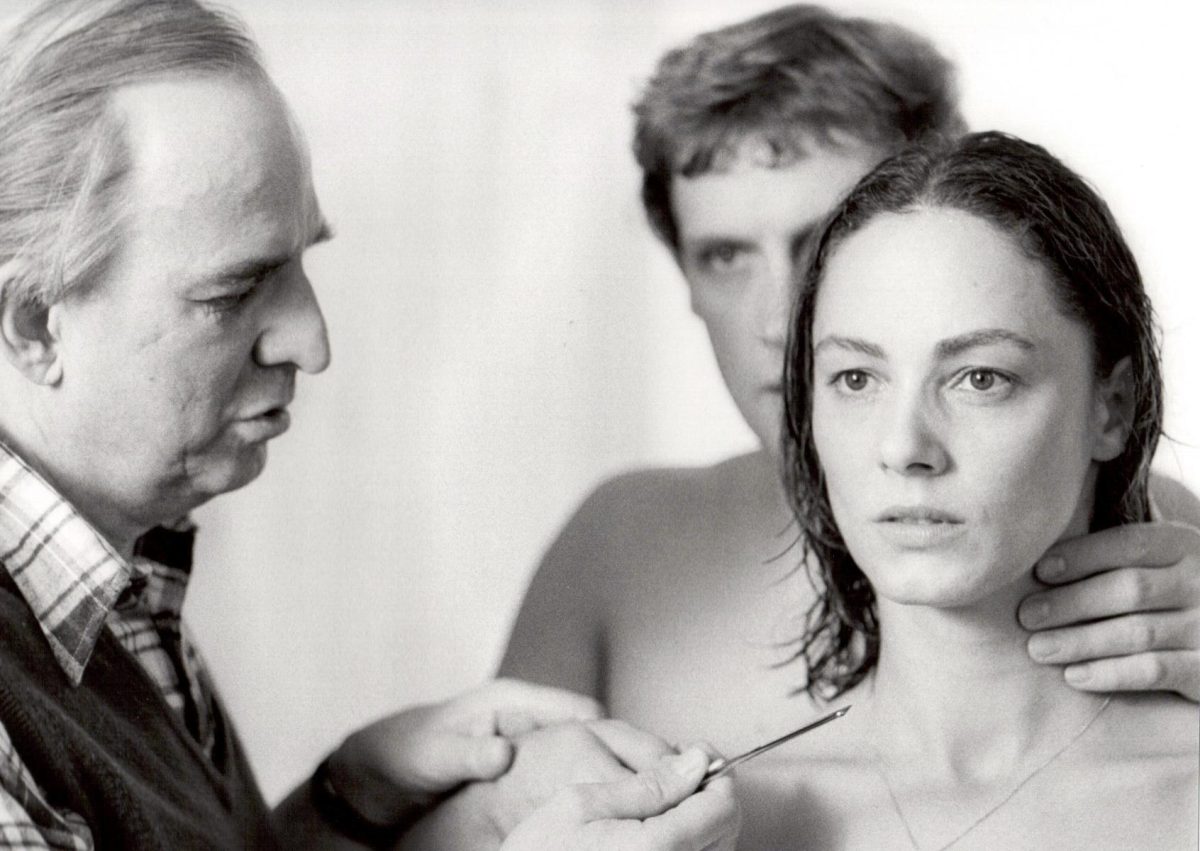

Whereas his favorite approach to the characters in the Gothic films was to let the camera sneak up on them, so that the person closest to the camera was seen from behind with the director assuming the position of a peeping Tom, Bergman allows the faces of his people in the chamber films to dominate the screen. A shot of the young boy Johan in The Silence shows him in a typical Bergman composition, with the human figure up front and a second figure in the background. But Johan’s face is turned towards the camera and towards us. There are numerous instances in the chamber films where we are caught in such tète-à-tètes with the characters. As one of my students pointed out to me, the faces staring at us in Bergman’s chamber films have a quizzical look about them5—they are faces that look like unresolved thoughts. They reveal nothing, but in their vacuous quality they fascinate us, as sleepwalkers do; we do not identify with them but we drift along with them.

Only occasionally can a Bergman close-up have the effect of an unexpected confrontation, such as the handheld camera sequence in Shame with Max von Sydow “tracking” down Liv Ullman through the frenzy of the pursuers eyes; or the instance in Persona where the mute Elizabeth Vogler is taking random pictures on the beach, then disappears from the screen only to pop back into the frame like a jack-in-the-box, to photograph us. (Like Godard again, no doubt, but also Bergman using a deliberate shock tactic of a close-up.)

Actually, such handlings of the close-up by Bergman are more than technical experiments with camera and audience reaction; first and foremost they are meant to tell us something about his characters. As always in Bergman’s case it is futile to approach his close-up style from the viewpoint of cinematic intention; rather, any changes in style must be related, I believe, to central themes, character motivation and other quite “literary” subjects.

THE CHAMBER FILMS

Not only is Bergman a film maker rooted in literary traditions; but his greatest contribution to the art of film making may very well be that he has shown that a film maker can use his medium to express his Weltanschauung and his feelings about life and death as consistently as composers have used notes and musical instruments and writers the various literary genres. We do not talk about a Beethoven “device” or a Dante “trick” but we agree that there is such a thing as a Beethoven mood and a Dante vision of life, and we proceed from there to examine not only how the mood and the vision are conveyed but also what constitutes the quality of that mood and that vision. Bergman’s chamber films invite us to pursue certain motifs rather than decipher a technical standard by which to judge them. Like all of his works these films possess a philosophical unity and a definite semantic dimension.

In the trilogy (Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, The Silence), emotions are expressed in facial look, in gesture. The first two words learned by Ester in the incomprehensible language in The Silence are naigo and kasi, “face” and “hand”. Rapport comes not through verbal communication but through touch and look or, if sound is used, through music (Bach). The reduced dialogue of the chamber films is not primarily a film makers attempt to liberate himself from verbal influence, but a questioning, through the cinematic medium, of the trustworthiness of the spoken word.

There is a great deal of parody of language in the chamber films, the most obvious instance being the highly histrionic tirade delivered by Minus in the play-acting sequence in Through a Glass Darkly. Likewise, people who take words too easily in their mouth are made to look ridiculous: Martin, Karins soothsayer of a husband, is always seen fumbling with his glasses or picking his nails. But we also find a persistent ethical examination of language in these films, which I think should be related to Bergman’s religious questioning and his portrayal of the father-child relationship.

Bergman grew up in a religious home; his father was a Lutheran minister, which meant that from early childhood reaching God became for Bergman related to speech and rhetoric. He has told us how he used to accompany his father on bicycle trips to the churches in rural Uppland, north of Stockholm, and how he came to know God through his fathers preaching, while he absorbed the atmosphere of the church through its murals and pictures. Bergman’s dichotomous view of God as both a distant object, revealing Himself through the Word, and a subjective need, a call for parental protection, can probably be traced back to this childhood situation.6

In this context it is helpful to go back briefly to one of Bergman’s prechamber films, The Seventh Seal, for it contains much of the philosophical basis of his later work. The Knight’s search for God, which constitutes the main theme of the film, is futile because his approach is all intellectual. He wants God to manifest Himself to him directly but as an object, through the spoken word. In the crucial confessional church sequence the Knight cries out:

I want knowledge, not faith, not suppositions, but knowledge. I want God to stretch out his hand toward me, reveal Himself and speak to me.

Later, as the Knight meets Tyan, the girl who is to be burned as a witch, he asks her about the devil; if the devil exists as objective reality, then God too, he argues with insane logic, must exist. Tyan assures him that she can feel the presence of the devil everywhere; but the Knight is skeptical and asks: “Has he told you that he exists?” Tyan answers without hesitation: “I know it.” But the Knight persists: “Has he said it?” Tyan now gets desperate: “I know it. You must see him somewhere, you must” But the Knight sees nothing but empty terror and he continues his search for a verbal message from God.

GOD: SECURITY OR SPIDER?

By the time he makes the chamber films, Bergman has discarded any notion of an autonomous God; God is now “reduced” to a subjective need, a projection of our fear of life and death—a thought hinted at but not embodied by the Knight in The Seventh Seal. How we experience God depends on the parental image we carry with us through life. In Through a Glass Darkly, David, the father and writer-in-crisis, is crucial to the way his two children feel about God. To Karin, the sick girl who is exploited by David as an interesting literary subject, God appears as an enormous spider coming out of a closet to devour her. But to Minus, the teenage son whom David consoles rather than punishes for his incestuous attraction to Karin, God becomes an expression of love. Karins God is a life-destroying parasite who whisks her off in a bug-like helicopter to an asylum. Minus’ God is a liberating force who allows him to scamper away on an adolescent run along the beach. What happens to Karin is, in Bergman’s terms, a fact of life, a piece of grotesque reality. What happens to Minus is a miracle, which explains why Bergman ended the film by having Minus stop as though struck by divine lightning and speak into the camera with a starry-eyed look on his face: “Father talked to me!”

Some viewers always experience David’s final speech as an act of hypocrisy or self-delusion. Bergman himself, however, did not originally intend the ending to have that effect. He wanted a spoken word of love, uttered by a parent to his child, to communicate a feeling of magic, a divine message. But while Bergman was shooting his next film, Winter Light, he told film-maker Vilgot Sjöman, who followed and recorded the making of the film,7 that he began to have serious doubts about the ending of Through a Glass Darkly before completing the film. It is these doubts that he pursues in Winter Light, where he smashes the concept of the loving and protective God, the God of self-centered adolescents. Winter Light’s main character, the pastor Tomas Ericsson, has to face one of his parishioners, the suicidal fisherman Jonas Persson. But instead of offering the frightened Jonas any words of consolation, Tomas, the Father of the flock, tells his parish “child” of his own doubts and of the time when his God changed from a “security god” to a “spider god”:

I am no good as a clergyman. I chose my calling because my mother and father were religious, pious, in a deep and natural way. Maybe I didn’t really love them, but I wanted to please them. So I became a clergyman and believed in God. An improbable, entirely private, fatherly God. Who loved mankind, of course, but most of all me. . . . Can you imagine my prayers? To an echo-God. Who gave benign answers and reassuring blessings? . . . Every time I confronted God with the reality I saw, he became ugly, revolting, a spider god—a monster.

Later in the film—wheezing from an attack of influenza; having learnt how Jonas has failed in his role of father and provider for a family by committing suicide; and having listened to Algot, the crippled church warden, refer to “Christ’s passion” as the moment of agony on the Cross when God did not answer his only son—Tomas nevertheless goes ahead with the church service although in view of the empty church he could have canceled it. Why does he insist on praising a god that does not respond? The film ends as Tomas, turning his pale and anxious face to the empty church, recites: “Holy, holy, holy, Lord God Almighty. All the earth is full of his glory . . .”

This time we know that the words are spoken by a non-believer. Language testifying to the love of God is now an empty formula, a meaningless ritual or, at the most, a verbal exercise in self-preservation.

About midway through Winter Light Tomas runs into a youngster in the schoolhouse, who tells him that he does not wish to become confirmed; and besides, he says, he is going to be an astronaut. To this boy, a member of the space age, the church seems an antiquated institution and spaceships now roam where God used to rule supreme.

The young boy in The Silence bears the same name as the youngster in Winter Light He also wears a symbolic nametag, a copy of Lermontov’s The Hero of Our Time. Through the eyes of this child Bergman records the after-effects of Tomas’ disillusionment. The camera angle in most of The Silence is low: reality photographed from a child’s level.

GOD AS FATHER REJECTED

What the film explores is Johan, the boy, facing a world that has lost touch with the divine—the original title of the film was God’s Silence—and one in which a traditional, masculine mode of life is being rejected or destroyed. Johan is the only one who encounters all the male figures in the film, from the officers in the opening train sequence (who frighten him) to the old waiter in the hotel, to whom he reacts as though he were a Dickensian bogeyman. Through Johan we see how all the male characters in the hotel are emasculated, deformed (the dwarfs), or killed symbolically: the bartender-lover is led and manipulated by Anna; an electrician fixing a light in the ceiling (seen amidst phallic-looking chandelier pendants) is shot down by Johan in a mock murder with a toy gun; the old waiter performs an obscene eating mime for the boy, a symbolic act of self-castration, as he bites off a long wiener lodged in a huge leaf of lettuce.

Johan’s father is absent and we are told that he is not likely to be around even after the boy returns home. But Johan lives in a sort of abortive family situation as he travels with his mother (Anna) and his aunt (Ester). Johan has a physical rapport with his mother even though she neglects him most of the time and will only love him when she can bring him into her world of narcissistic obsession with her body, which she pampers with ritual ablutions or abuses, not in self-disgust so much as in defiance of a moralistic past, surviving (to her) in her sister.

Ester arouses Johan’s intellectual curiosity. Johan’s relationship to the two women is made clear early in the film; in the train he asks Ester about a sign in the foreign language; moments later he goes over to put his head on Anna’s shoulder. Ester plays the role of father substitute to Johan, initiating him into the world of secret signs. But unlike a conventional parent (and prophet) figure, Ester does not have to exert her authority (she asks Johan if he has washed his ears but does not insist that he do it). For Johan it can be a somewhat comforting relationship—except when Ester demands a physical response from him.

Although the visual perspective of The Silence is Johan’s, much of its philosophical focus is on Ester. An alienated believer in verbal communication (she is a translator by profession) she re-enacts the Knight’s role in The Seventh Seal, for like him she challenges, without much success, an unknown reality through words. But Ester also carries on the part of Tomas Ericsson in Winter Light; like Tomas she oscillates (in the now rather than in a remembered time continuum) between “an orderly world in which everything made sense” and a shattered reality creating a mood of great despair and helplessness. Ester’s momentary life-sustaining ritual is her work at the typewriter: a precise shot that shows her neatly dressed and in control. But the forces of disintegration are strong at work: most of the time we see Ester plagued by attacks of suffocation (the psychosomatic disease of those who have lost faith in the word?). She appears sloppily dressed; she gets drunk, masturbates, breaks down with jealousy over Anna’s erotic escapades; she smokes furiously and creates a veritable mess of her room.

Ester’s lesbianism is not as revealing as is her emotional dependence upon Anna. During her initial attack on the train Ester recovers as soon as Anna sends Johan away and devotes herself to her sister. Little by little Ester’s search for parental love and support emerges. She thrusts the role of mother on Anna, begging her like a whimpering child to sit at her bedside; and she identifies with Johan at least once when she confesses her love for Anna (“We love Mommy, you and I”). Frequently the placing of the two sisters in the rooms is reminiscent of the way Jonas Persson and Tomas were photographed in Winter Light, with the parental figure in the foreground, strongly illuminated, and the other person in the background, “small like a child” (Winter Light).

INTELLECTUALISM EQUALS PATERNALISM

Yet, Anna fears Ester whom she looks upon as a moralistic extension of her father. She resents Ester’s intellectual achievement and she is indifferent to the written message Ester gives Johan at the end. To Anna silence is comforting, for she can only see and use language as a destructive weapon and connects it with parental authority. In her most vicious verbal attack on Ester she reminds her sister of their father, who weighed 400 pounds and who, in his absent enormity, takes on almost mythic qualities.

When Anna leaves Ester behind to die, she finally rejects the world of language and fatherly supervision—all “empty principles” as she has told Ester earlier. But Ester does not possess Anna’s strength or indifference. She transfers the protective father image to the old waiter; she prods him into giving her words in the foreign language and lets him baby her with a bottle of brandy—the alcoholic’s sacrament. But the waiter cannot do much for Ester. This mumbling and (in the moment of crisis) quite helpless father figure is indeed nothing but a dried-up goblin of a man, who totters out of the room with Ester’s downy bedding thrown over his shoulder, like some Santa Claus carrying away his sack. The protective father figure, the god-against-fear, is relegated to the realm of death and myth.

As he finished the trilogy, Bergman declared that he was done with religious matters. From then on the artist steps into the foreground (Persona, Hour of the Wolf, Shame, The Passion), and although this figure may possess parasitical qualities (as did David in Through a Glass Darkly) he (or she) loses more and more of his mesmeric hold over those living with him and emerges in the end as a frightened, pathetic victim of his own frustration rather than as a fallen idol or failing father.

With the trilogy, then, it would seem that Bergman brings to a close that gradual shift in mans approach to and experiencing of God, which had obsessed him since The Seventh Seal; it is a shift in attitude from an intellectual search for the transcendental to an examination of God as a therapeutic or authoritarian parental figure. In mood we travel from doubt and frustration to a sense of negative certainty. This development is paralleled by an increasingly greater emphasis on the human face, at the same time as the verbal smokescreen that sometimes mars Bergman’s earlier films disappears.

It seems important to recognize that the relevance of language as a basis for film making is no longer a point argued by Bergman on a technical level, but rather is connected with his evolving vision of life. When God dies away, when the father fails or withdraws from his child and leaves it alone, language loses its communicative and healing power. Bergman’s exploration of the god-parent-child syndrome takes then, in part, the form of a philosophical testing of language. His conclusion is that conventional language cannot be used by people to convey love. Nor can it be trusted, since it tends to destroy relationships or else lull people into a false sense of security. The perceptive and sensitive individual may at first cling to this verbal reassurance, but he will ultimately be driven to challenge it.

NOTES

1. Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman, Simon & Schuster (New York: 1960), p. XVII

2. A term analogous to Strindberg’s chamber plays, written in 1907-08, in which the Swedish playwright tried to convey, through the portrayal of a small group of people confined to a single locale, a view of life structured like a musical composition, i.e. as variations of a theme.

3. Quoted in Hollis Alpert, “Style Is the Director,” Saturday Review of Literature, December 23, 1961, p. 41.

4. Ibid., p. 40.

5. Randolph Pitts of the University of California at Berkeley, from whose insights and technical know-how I learned a great deal.

6. Cf. Bergman’s statement, made to Jean Beranger, that “to make films is to plunge to the very depth of childhood.”

7. Vilgot Sjöman, L 136, P. A. Norstedt & Söner (Stockholm: 1963), p. 47.

Source: Cinema Journal, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Autumn, 1970), pp. 23-33