by William Wolf

Ingmar Bergman stands outside his ranch house on Fårö, his Swedish island sanctuary, one arm affectionately around his wife, the other waving an enthusiastic welcome. He flashes a broad smile, almost a grin. There is nothing to suggest the brooding genius one might expect from stories about Bergman’s anxieties and from his films that have probed despair and isolation.

During the next three hours it would become apparent that there is a new, liberated Ingmar Bergman. At 62, he is as work-obsessed as ever and worried that his filmmaking days may be ending, but the upheaval in his life—set off when he was hauled out of a rehearsal at the Royal Dramatic Theater, in Stockholm, in January 1976 and grilled at police headquarters by over zealous tax inspectors —forced him out of the shadows. Now he not only enjoys traveling and working abroad but has a new interest—playing paterfamilias to the clan resulting from his string of marriages, official and unofficial.

Although publicity-shy, he has even agreed to help promote Scandinavian films. In past visits to New York, Bergman tried to remain incognito. This week, he is due to arrive for the opening of the Museum of Modem Art’s “Scandinavia: New Films” program, which begins October 30 and marks a combined effort by Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, and Finland to crack the American market. He will also be plugging his own new German film, From the Life of the Marionettes, another searing dissection of a marital relationship, this one exploding in murder. Marionettes won’t be shown at MOMA, but the series will include his fascinating Fårö Document 1979, an update of the film he made ten years earlier, depicting the rigors of life on his cherished island.

En route to the Fårö (pronounced For-EH) rendezvous with the director, I wondered how much more one could expect from a man who has already explored the soul and has analyzed men and women in relation to themselves, to others, and to the profound philosophical questions that have perplexed human beings through the ages. Can he equal or surpass such masterpieces as The Seventh Seal, Winter Light, Wild Strawberries, The Silence, Persona, The Passion of Anna, Cries and Whispers, Scenes From a Marriage?

Geographically, Bergman is as remote as some find his films. First there’s a chartered plane from Stockholm to the ancient city of Visby, on the Baltic island of Gotland, a 40-minute bouncing ride to a car ferry, a 15-minute chug across the water to bleak-looking Fårö, another 15 minutes past mostly barren land, then along a winding, treelined dirt road leading to fenced-off property with a sign warning, security alarm. Plus special permission from the Swedish military authorities, since Fårö, facing the Soviet Union, 100 miles away, is an outpost in Sweden’s defense system.

Are there radar installations?

“I’m not allowed to say,” Bergman demurs, laughing at the idea of attaching security importance to this tiny isle. Then he leads the way along the stony beach to show off his panoramic sea view. “I first came here to film Through a Glass Darkly and fell in love with the island. But I had a lot of trouble getting permission when I decided to build this house. You need permission for everything. It’s a simple house.” True, the gray wooden structure isn’t ostentatious, but it is impressively spacious, with a sizable swimming pool hidden behind it. “Mostly I enjoyed it here because it is so peaceful. When the sea is silent, it is very strange. But it is never frightening.”

Suddenly his tone grows somber. He could have been setting the scene for one of his films. “There was a time when I was frightened. It happened one night about five years ago, when there was a strange light to the sky. I had this horrible feeling that something was going to happen. And the next morning they found two fishermen had drowned just here.” His mellifluous voice is already beginning to have a mesmerizing effect; his manner establishes immediate intimacy, and he laughs easily and frequently.

“Let’s talk seriously after lunch,” he says pleasantly but decisively. His wife, Ingrid (another Ingrid Bergman), to whom he has been married for ten years, has prepared a smorgasbord that includes gravlax, salad, and a huge bowl of luscious raspberries (“They were picked today by a neighbor”) served with fresh cream. Although it is midday, candles illuminate the table in the dining area of their large, knotty-pine-paneled, modern kitchen. Bergman rations himself to a small bowl of raspberries mixed with sour milk. We have coffee in the simply furnished living room, which contains a few paintings and a driftwood sculpture. Near the elevated fireplace, wood is neatly stacked. There is a large television and a videotape machine, with a shelf full of cassettes. In a corner, a handsome grandfather clock ticks away as if auditioning for a Bergman film.

Bergman doesn’t recoil at being asked whether he has anything more to say in his films or is in danger of drying up. “I have thousands of ideas. That’s not the problem, because I still have an enormous desire to make pictures. I have many things to talk about because of my fascination with the human being, the human face—which fascinates me more and more—all the dimensions of reality, and the conditions of human life, of the human being.” But he confesses to the doubts that have been nagging at him in the last decade.

“The problem is that I’m 62 years old. I have been in this business 40 years, and more and more I feel it physically. I get tired. Making a picture is a very tough job. It gets harder and harder, and I can feel that my health isn’t what it was five or ten years ago. I don’t think that has affected my film-making yet, but there is a risk that one day I’ll feel that, no, I don’t want any more, I’m too tired. Not bored, but too tired to start a new picture. I have decided that I don’t want to wait for somebody to come in and tell me, ‘Ingmar, it is better for you not to make this picture because physically you can’t take it anymore.’ So one day I’ll say to myself, ‘No, Ingmar, it’s over.’

“Sometimes during the last ten years, when I have been shooting a picture, I’ve been very close to this decision. You know, I’m sleepless—that’s my great problem. I sleep no more than four or five hours a night. I can be very tired in the morning when I have to go to the studio, and I think this will be my last picture, because I can’t stand it anymore. Then the picture is finished, and I rest a little.’’

Could he really walk away from it all? “Oh yes, oh yes, oh yes. Because the theater is there, and that’s something else. You can come at 10 a.m., go to the rehearsal room, rehearse for four and a half hours, and say, ‘Today it was not so very good, but it will be better tomorrow, or Saturday, or Monday.’ So, I hope to have the opportunity to work in the theater all my life.’’

Bergman has been staging plays in Munich, but there has been sporadic talk of his coming to New York to do Ibsen’s Rosmersholm, with Liv Ullmann. “I would find that fascinating, but the problem in New York is that there is one star. The other actors are good but not excellent. In Munich you can have the best actors for all the parts. And in New York, rehearsal time is so short—about four weeks. In Munich I rehearsed The Three Sisters for fifteen weeks. And even if you get bad reviews in four papers, the audiences are so educated that they don’t believe what they read and go to see for themselves.”

Bergman’s film company is based in Munich, where he spends half the year. For tax purposes, he can’t spend more than six months a year in Sweden, but Bergman now feels free to return to the homeland he fled in bewilderment and anger. The charges of fraud crushed him and precipitated a nervous break-down. Subsequently, a new Swedish administration exonerated him completely and apologized.

“It was almost five years ago, and it’s over, far away. The authorities made a big mistake. It is very seldom that a bureaucracy apologizes. But what happened almost killed me. Of course, it was also stimulating and good for me, because I had once thought it impossible to work abroad. But I had to go away somewhere. I went to New York and Los Angeles and Paris and Berlin and Copenhagen and Paris again, and Munich, and back to Los Angeles. It was fascinating. Anyhow, this fear of traveling, fear of flying—I don’t have it anymore. But we don’t want to go over everything again. It was part of a political attack. They wanted a scapegoat, but the whole thing is over.”

Bergman’s wife is more agitated, less forgiving. “My heart starts beating fast when I think of it. They treat people like Ingmar worse than anyone else.”

‘‘Please, Ingrid, let’s not go into it,” he implores.

Mrs. Bergman is known to be extremely devoted to her husband and protective of him. Unlike the actresses who have shared his life (Harriet Andersson, Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann, and who knows how many others), she nurtures no desire for an artistic career. Formerly in her family’s import-export business, she now manages the details of Bergman’s production company. The Bergmans have no household help; Ingrid does everything herself. About to go away for three days, she has prepared all of her husband’s food in advance. He won’t answer the phone, so she does; she encourages and organizes family reunions, even though it means a staggering workload.

“The first time all of our children ever met was two years ago, for Ingmar’s sixtieth birthday,” she says. “They liked it tremendously and come back now and again. They really know each other now and like to sit talking night after night, like sisters and brothers. This summer they were all here again.”

Bergman is ebullient in describing the summer reunion. A few years ago, Liv Ullmann told me of Bergman’s difficulty in relating to their daughter, Linn, but predicted that when Linn grew older, they’d have more in common. “All eight of my children were here, and Ingrid has four children from another marriage. They were here too. We had boyfriends and girl friends, wives and husbands, and grandchildren. Sometimes it’s very tiring, so I have to go into the studio to rest. But I like it tremendously.”

Bergman’s work facilities on Fårö are in another house a few kilometers away. “I bought a farm that’s 150 years old, and there I have a screening room, cutting tables, everything I need.” His move to Munich posed many problems—adjusting to his self-imposed exile, working in languages other than Swedish. His first expatriate film was The Serpent’s Egg. “The film was a complete failure, but even failures can be interesting.” After his next film, the acclaimed Autumn Sonata, made in Norway, Bergman returned to Fårö to make Fårö Document 1979. “In a way the film was a medicine, a remedy, coming back here, you know. Here are my sources, my roots. It’s the only place in the world where I feel really at home. There are about 500 inhabitants on the island, and I did a lot of interviews. To talk with my friends here, their problems, their lives, to look at them when they are at work—this was extremely personal to me.”

Bergman has finished a new script for his next project. He is reluctant to talk about a work in progress, but someone close to him who has read the screenplay says that it again draws upon his childhood experiences. Fanny and Alexander, geared for both a television series and for a shorter version for theatrical distribution, is budgeted at $7 million and will star Max von Sydow, Liv Ullmann, and Erland Josephson. Although set in 1910, the analogy is obvious. Von Sydow plays a minister whose rigidity resembles the well-known authoritarianism of Bergman’s father, also a minister. He locks his children in a closet for punishment, as Bergman’s father did, and comes to a horrendous end. His sister catches fire in her bed, runs to him for help, and they both burn to death.

Bergman has often spoken about the scars left by his childhood. “But my neuroses are not in relation to my work. At least I have the illusion that my work is very unneurotic.” Bergman fled his home and didn’t see his parents for four years. Eventually he came to a better understanding with them. He even finds positive results amid the psychic damage. Punctuality is one. “As a child I was a dreamer. Time didn’t exist for me, and my father was not very sentimental in that respect, so he educated me in a very tough way. When I went to school I could be one, two, or three hours late when I came home. That was not very good for my backside. Now I hate to steal time from anybody, because I hate when time is stolen from me. If I say to somebody that we will meet at ten o’clock, I will be there five minutes before. So I am grateful to my father.”

Talking with Bergman, it is easy to understand how he elicits such magnificent performances. Harriet Andersson says, “When he puts his arm around you, watch out.” He looks at you directly, and his gentle, intimate manner suggests how he coaxes actors into doing anything he asks by inspiring their unswerving trust. Gunnel Lindblom, a Bergman actress who now directs her own films, thinks she understands why he is particularly successful directing women: “It isn’t just that he likes women—he is interested in learning more about them.”

How does Bergman describe his methods?

“It depends on whether you are making a film or directing a play. In the theater you can stop the work and sit down with an actor to discuss the problems. Filming is, of course, a sort of factory. You have to make three minutes of the picture every day. Everything, every detail, must be absolutely prepared. Everybody, not only the actors, but all my collaborators, must know exactly what to do at every moment. Only then can we improvise.

“Most important, I think, is to create an atmosphere of security, of calm, of silence in the studio. It’s a very tough job, most tough for the actors because they are so exposed. They stay there with their voices and their faces and require a feeling of absolute confidence. They must be relaxed, and I have to create that atmosphere.”

I tell him that actress Ingrid Bergman was surprised at his way of getting her to express herself in Autumn Sonata, when he would tell her to think of things that had nothing to do with the scene. “Oh, yes,” he confirms. “It is meaningless to talk in an intellectual way when our situation is completely emotional. The intellectual discussion must have been cleared out before the start of the picture, because once we are completely in the middle of the emotional process, you have to talk in emotional terms. You can say to an actor, ‘You feel heavy like a stone,’ and an actor knows exactly what you mean and transforms his body. And when he has the lines to complete the emotion, then you will have an expression. In the beginning, Ingrid Bergman was very angry, because when we were shooting I didn’t look at her. ‘Why do you not look at me?’ she asked. I said, ‘If I hear that your voice is correct, I know that you look correct.’ ”

Hollywood has always been a lure for foreign directors. Now that he likes to travel, would Bergman venture into Lotusland? He is ambivalent. “I very much admire the American way of filmmaking. It’s very vital, and extremely stimulating. And American directors have taught me a lot. In the 1930s, I started my filmgoing with American films. I would see two or three movies a day. Of course, I had to become good friends with the projectionists, because I had no money. I learned from the films of Billy Wilder, Ernst Lubitsch, George Cukor. To go to America, to live there, to make a picture with American actors and in American studios could be a marvelous, exciting experience, but just an experience. It could be very difficult, like going to Japan and trying to make a samurai picture. And if an American director tries to make a picture in European style—as, for instance, Woody Allen tried with Interiors—he comes into great difficulties. I think the picture is wonderful—I love it. But the critics didn’t.” (This critic agrees with Bergman.)

Bergman has a personal collection of some 500 films. “I’ve concentrated on silent films and early talkies because the other pictures I can get from the companies. In the summer, almost every evening, we went to the movies in the barn. While the children were here, we saw about 40 pictures. Then we sat together and discussed them. It’s lots of fun. I like very much to go to the movies. There are not many directors who do. It’s from my childhood. Fellini, fratello mio, and I feel the same way. He likes to go to the movies more than to the theater. I almost never walk out on a movie. Maybe once or twice.”

Is there any new direction that he would like to take in his filmmaking? A new approach, a new technique perhaps?

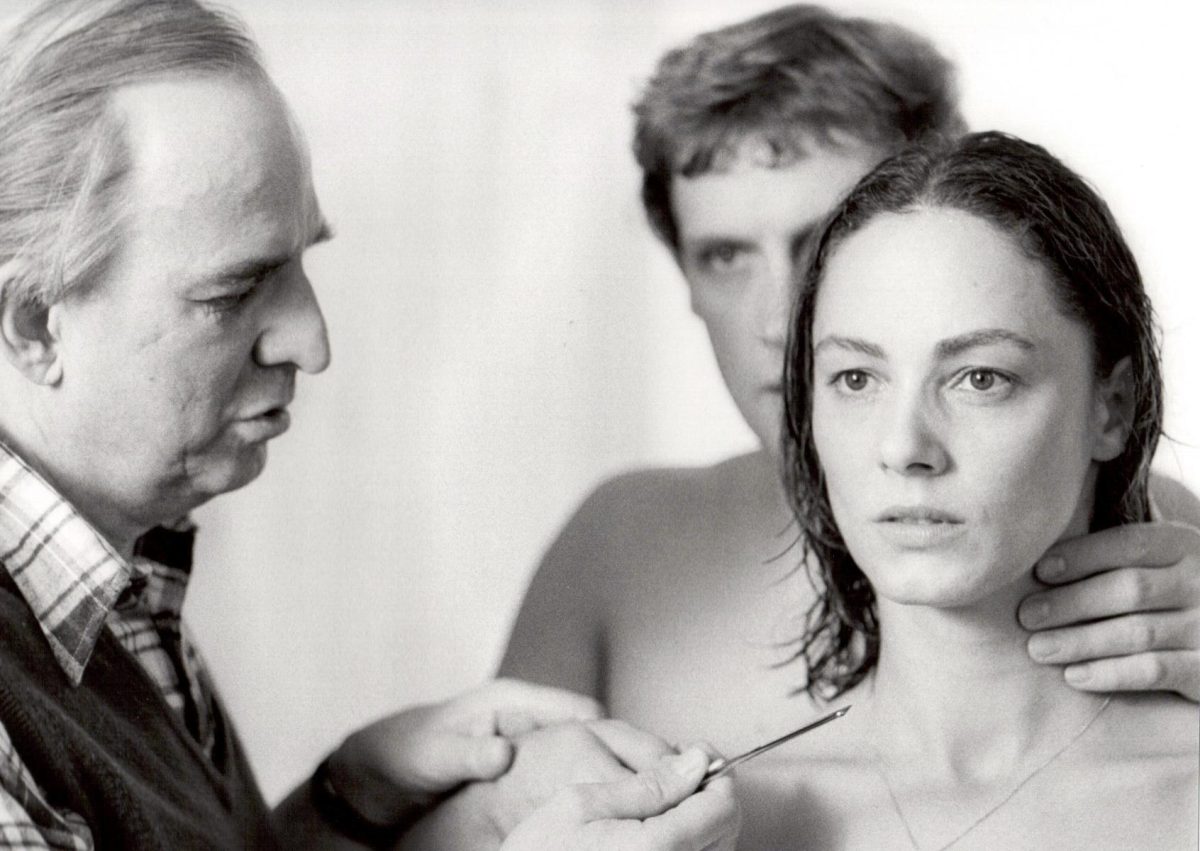

“I would like once in my life to make a 120-minute picture with just one close-up. I think it’s impossible, but I would love to do it once. To have the right actor and to have the talent to accomplish this. It would be the most fascinating experience of all, just to look with the camera. I am a voyeur. To look at somebody, to find out how the skin changes, the eyes, how all those muscles change the whole time—the lips—to me it’s always a drama. Sven [the brilliant cinematographer Sven Nykvist, Bergman’s longtime collaborator] and I have been experimenting with how to light close-ups, and perhaps to make that picture, black and white would be better than color, because color is never true. Black and white is, strange to say, more true because then your fantasy is created; you have created it yourself.

“We made From the Life of the Marionettes in black and white, the first picture in almost ten years we did that way. We start in color, and then after about three or four minutes go over to black and white, and then the last two or three minutes are in color. Perhaps I’m wrong, but to me the great gift of cinematography is the human face. Don’t you think so? With a camera you can go into the stomach of a kangaroo. But to look at the human face, I think, is the most fascinating.” Bergman refused to permit a professional photographer to come to the island to try to capture his face, but he says “of course” when I ask him and his wife to pose for an amateur. While fiddling with the focusing, I suggest, “We should have Sven Nykvist here.” Bergman laughs. “Oh, no. He’s a very bad photographer. You can’t imagine how bad until you see his private pictures.”

New York Magazine, October 27, 1980