Flesh

by Pauline Kael

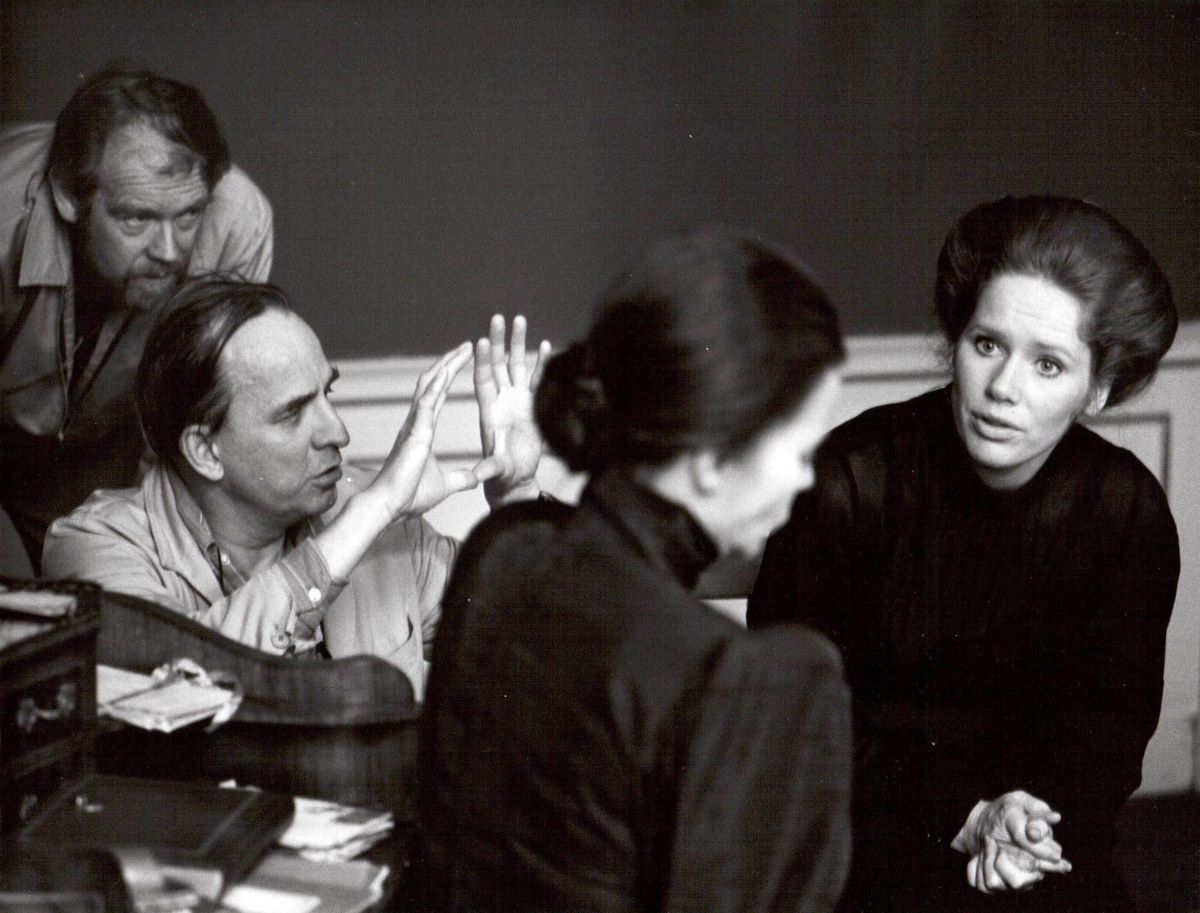

Cries and Whispers is set in a manor house at the turn of the century where Agnes (Harriet Andersson), a spinster in her late thirties, is dying of cancer. Her two married sisters have come to attend her in her final agony — the older, the severe, tense Karin (Ingrid Thulin), and the shallow, ripe, adulterous Maria (Liv Ullmann) — and they watch and wait, along with the peasant servant Anna (Kari Sylwan). We see their interrelations, and the visions triggered by their being together waiting for death and, when it comes, by death itself. But the gliding memories, the slow rhythm of the women’s movements, the hands that search and touch, the large faces that fill the screen have the hypnotic style of a single dream. It is all one enveloping death fantasy; the invisible protagonist, Ingmar Bergman, is the presence we feel throughout, and he is the narrator. He is dreaming these fleshly images of women that loom in front of us, and dreaming of their dreams and memories.

Bergman is not a playful dreamer, as we already know from nightmarish films like The Silence, which seems to take place in a trance. He apparently thinks in images and links them together to make a film. Sometimes we may feel that we intuit the eroticism or the fears that lie behind the overwhelming moments in a Bergman movie, but he makes no effort to clarify. In a considerable portion of his work, the imagery derives its power from unconscious or not fully understood associations; that’s why, when he is asked to explain a scene, he may reply, “It’s just my poetry.” Bergman doesn’t always find ways to integrate this intense poetry with his themes. Even when he attempts to solve the problem by using the theme of a mental breakdown or a spiritual or artistic crisis, his intensity of feeling may explode the story elements, leaving the audience moved but bewildered. In a rare film such as Shame, the wartime setting provides roots for the anguish of the characters, and his ordering intelligence is in full control; more often the intensity appears to have a life of its own, apart from the situations, which don’t account for it and can’t fully express it. We come out of the theater wondering about Bergman himself and what he was trying to do.

Like Bergman, his countryman Strindberg lacked a sovereign sense of reality, and he experimented with a technique that would allow him to abandon the forms that he, too, kept exploding. In his author’s note to the Expressionist A Dream Play (which Ingmar Bergman staged with great success in 1970), Strindberg wrote:

The author has sought to reproduce the disconnected but apparently logical form of a dream. Anything can happen; everything is possible and probable. Time and space do not exist; on a slight groundwork of reality, imagination spins and weaves new patterns made up of memories, experiences, unfettered fancies, absurdities, and improvisations.

The characters are split, double, and multiply; they evaporate, crystallize, scatter, and converge. But a single consciousness holds sway over them all — that of the dreamer. For him there are no secrets, no incongruities, no scruples, and no law.

That is Bergman’s method here. Cries and Whispers has oracular power, and many people feel that when something grips them strongly it must be realistic; they may not want to recognize that being led into a dreamworld can move them so much. But I think it’s the stylized-dream-play atmosphere of Cries and Whispers that has made it possible for Bergman to achieve such strength. The detached imaginary world of the manor house becomes a heightened form of reality — more literal and solid, closer than the actual world. The film is emotionally saturated in female flesh — flesh as temptation and mystery. In almost every scene you’re aware of bodies and parts of bodies, of the quality of Liv Ullmann’s skin and the miniature worlds in the dying woman’s brilliant eyes. The almost empty rooms are stylized, and these female bodies inhabit them overpoweringly. The effect — a culmination of the visual emphasis on women’s faces in recent Bergman films — is intimate and hypnotic. We are put in the position of the little boy at the beginning of Persona, staring up at the giant women’s faces on the screen.

In the opening shots, the house is located in a series of autumnal landscapes of a formal park with twisted, writhing trees, and the entire film has a supernal quality. The incomparable cinematographer Sven Nykvist achieves the look of the paintings of the Norwegian Edvard Munch, as if the neurotic and the unconscious had become real enough to be photographed. But, unhappily, the freedom of the dream has sent Bergman back to Expressionism, which he had a heavy fling with in several of his very early films and in The Naked Night, some twenty years ago, and he returns to imagery drawn from the fin de siècle, when passion and decadence were one.

Bergman has often said that he likes to use women as his chief characters because women are more expressive. They have more talent for acting, he explained on the Dick Cavett show; they’re not ashamed of looking in the mirror, as men are, he said, and the camera is a kind of mirror. It would be easy to pass over this simplistic separation of the sexes as just TV-interview chitchat if Bergman were still dealing with modern women as characters (as in Törst, Summer Interlude, Monika), but the four women of Cries and Whispers are used as obsessive male visions of women. They are women as the Other, women as the mysterious, sensual goddesses of male fantasy. Each sister represents a different aspect of woman, as in Munch’s “The Dance of Life,” in which a man dances with a woman in red (passion) while a woman in white (innocence) and a woman in black (corruption, death) look on. Bergman divides woman into three and dresses the three sisters for their schematic roles: Harriet Andersson’s Agnes is the pure-white sister with innocent thoughts; Liv Ullmann’s Maria, with her red-gold hair, wears soft, alluring colors and scarlet-woman dresses with tantalizing plunging necklines; and Ingrid Thulin’s death-seeking Karin is in dark colors or black. The film itself is predominantly in black and white and red — red draperies, red wine, red carpets and walls, and frequent dissolves into a blank red screen, just as Munch frequently returned to red for his backgrounds, or even to cover a house (as in his famous “Red Virginia Creeper”). The young actress who plays Agnes as a child resembles Munch’s wasted, sick young girls, and the film draws upon the positioning and look of Munch’s figures, especially in Munch’s sickroom scenes and in his studies of the laying out of a corpse. Cries and Whispers seems to be part of the art from the age of syphilis, when the erotic was charged with peril — when pleasure was represented by an enticing woman who turned into a grinning figure of death. “All our interiors are red, of various shades,” Bergman wrote in the story (published in The New Yorker) that was also the working script. “Don’t ask me why it must be so, because I don’t know,” he went on. “Ever since my childhood I have pictured the inside of the soul as a moist membrane in shades of red.” The movie is built out of a series of emotionally charged images that express psychic impulses, and Bergman handles them with the fluidity of a master. Yet these images are not discoveries, as they were for Munch, but a vocabulary of shock and panic to draw upon. Munch convinces us that he has captured the inner stress; Bergman doesn’t quite convince, though we’re impressed and we’re held by the smoothness of the dreamy progression of events. The film moves with such eerie slow grace that it almost smothers its own faults and absurdities. I had the divided awareness that almost nothing in it quite works and, at the same time, that the fleshiness of those big bodies up there and the pull of the dream were strong and, in a sense, did make everything work — even the hopeless musical interludes (a Chopin mazurka, and a Bach suite for unaccompanied cello played romantically) and the robotized performances of all but Harriet Andersson. Still, there’s a dullness at the heart of the movie, and the allegorical scheme leads to scenes that recall the conventions of silent films and the cliches of second-rate movie acting. The dying Agnes is devout as well as innocent. Liv Ullmann’s Maria seduces a visiting doctor with the telegraphic leering of a Warner Brothers dance-hall hostess. Her conversation with him is a variant of the old “You’re dirt, but so am I; we deserve each other,” and the picture supports the doctor’s view of her—that her physical desires and flirtatiousness are signs of laziness and vacuity. And that peasant Anna— the selfless, almost mute servant, close to nature, happy to do anything for the three sisters — has the proud-slave cast of mind that is honored in barrelfuls of old fiction. When Anna bares her breast to make a soft pillow for the dying Agnes, and, later, when she gets into bed, with her thighs up, supporting the dead Agnes in a sculptural pose that suggests both a “Pieta” and “The Rape of Europa,” these are Bergman’s visions of the inner life of a peasant mindlessly in harmony with the earth. The latter pose is altogether extraordinary, yet the very concept of Anna as a massive mound of comforting flesh takes one back (beyond childhood) to an earlier era. Cries and Whispers feels like a nineteenth-century European masterwork in a twentieth-century art form.

The words, which are often enigmatic, are unsuccessful attempts to support the effects achieved by the images. Most of Ingrid Thulin’s acting as Karin belongs in a frieze of melodrama, alongside such other practitioners of the stately-stony dragon lady in torment as Gale Son-dergaard and Cornelia Otis Skinner. Karin shuts her eyes to blot out her own despair and expresses herself in such dialogue as “I can’t breathe anymore because of the guilt” and “Don’t touch me!” and “It’s all a tissue of lies.” Most of her lines can be reduced to “Oh, the torment of it all!” — which actually isn’t much of a reduction. That’s how she talks when she isn’t prowling the halls suffering. The suicidal, hate-filled Karin represents Bergman’s worst failure in the movie. She escapes from the stereotype only twice — in a moment of manic humor when she complains of her disobedient big hands while wiggling them, and when she acts out a startling Expressionist fantasy of self-mutilation (followed by more lip-licking pleasure than the fantasy can quite accommodate). It is the advantage of the dream-play form that these two scenes appear to belong here, and people don’t have to puzzle about them afterward, as they did with comparable passages in, say, The Silence. If Bergman can’t make us accept the all-purpose complaints about guilt and suffering that are scattered through his films, his greatest single feat as a movie craftsman is that he can prepare an atmosphere that leads us to accept episodes brimming with hysteria in almost any makeshift context. Here, as Strindberg formulated, the dream context itself makes everything probable; the dreamer leads, the viewer follows. In Cries and Whispers Bergman is a wizard at building up a scene to a memorable image and then quickly dissolving into the red that acts as a fixative. The movie is structured as a series of red-outs. We know as we see these images disintegrate before our eyes that we will be taking them home with us. But Bergman doesn’t have Strindberg’s deviltry and dash; he uses a dreamlike atmosphere but not the language of dreams. He stays with his obsessional images, and his repressed, grave temperament infects even his technical surrender to the dream. (Strindberg, by contrast, was making twentieth-century masterworks in a nineteenth-century art form.)

Who knows how we would react if someone came back from the dead? But here, as in an old Hollywood movie, everyone reacts as scheduled. When Agnes’s decaying corpse speaks, pleading for Karin to comfort her, Karin says she won’t, because she doesn’t love her; Agnes calls next for Maria, who also fails the test, fleeing in horror when the dead woman tries to kiss her. It is, of course, as we knew it would be, the peasant-lump Anna who is not afraid of holding the dead woman. This gothic-fairy-tale test of love is shown as Anna’s dream, but it is also integral to the vision of the film, which is about the sick souls of the landed-gentry bourgeoisie. I think it is because Bergman lacks the gift for bringing order out of his experiences that he falls back on this schematism. It would be ludicrous if he similarly divided “man.” The men in the movie are a shade small — so narrowly realistic they’re less than life-size — while the women are more than a shade too splendidly large and strange: allegorical goddesses to be kept in the realm of mystery; never women, always facets of “woman.”

Death dreams that come, equipped with ticking clocks and uncanny silences and the racked wheezes of the dying are not really very classy, and Bergman’s earnest use of gothic effects seems particularly questionable now, arriving just after Buñuel, in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, has turned them on and off, switching to the spooky nocturnal as a movie joke. But even when Bergman employs sophisticated versions of primitive gothic-horror devices, he is so serious that his dream play is cued to be some sort of morality play as well. Other chaotic artists (Lorca, for example, in his dream play If Five Years Pass) haven’t been respected in the same way as Bergman, because their temperaments weren’t moralistic. But Bergman has a winning combination here: moral + gothic = medieval. And when medieval devices are used in the atmosphere of bourgeois decadence, adults may become as vulnerable as superstitious children.

Bergman is unusual among film artists in that he is an artist in precisely those terms drawn from the other arts which some of us have been trying to free movie aesthetics from. He is the movie director that those who are not generally interested in movies can recognize as an artist, because of the persistent gloom and weight of his work. It is his lack of an entertaining common touch — a lack that is extremely unusual among theatrical artists and movie artists — that has put him on a particular pinnacle. His didact’s temperament has obtained this position for him, and although he is a major film artist, it’s an absurd position, since he is a didact of the inscrutable. He programs mystery. Cries and Whispers features long scenes in which the camera scans the faces of Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Thulin as they talk and touch and kiss (scenes similar to the ones that led some people to assume that the sisters in The Silence were meant to be Lesbians); the camera itself may be part of the inspiration for these scenes, and perhaps some male fantasy of Sisterhood Is Powerful. The eroticism of this vision of sisterly love is unmistakable, yet the vision also seems to represent what Bergman takes to be natural to women. The dreamer, fascinated, is excluded from what he observes, like the staring, obsessed boy in Persona. This film is practically a ballet of touching, with hands, like the hands of the blind, always reaching for faces, feeling the flesh and bones. Maria’s husband touches her face after she has committed adultery, and feels her guilt. Touching becomes a ritual of soul-searching, and Karin, whose soul has been rotted away, is, of course, the one who fears contact, and the one who violates the graceful ballet by — unforgivably — slapping Anna. Even the dead Agnes’s hands reach up to touch and to hold. Didacticism and erotic mystery are mingled — this is Bergman as a northern Fellini. Strindberg’s dream plays do not have the great tensions of the plays in which he struggled to express his ferocity, and this movie, compellingly beautiful as it is, comes too easily to Bergman. The viewer can sink back and bask in flesh, but to keep scanning woman as the Other doesn’t get any of us anywhere.

The New Yorker, January 6, 1973