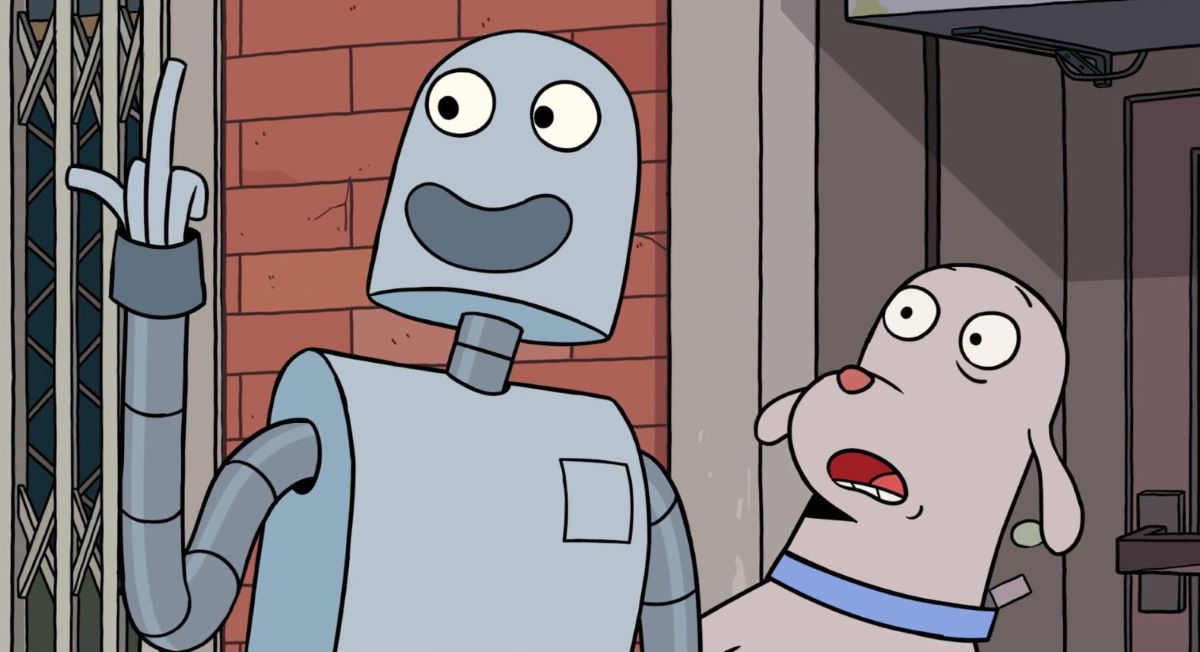

Robot Dreams

Pablo Berger’s animation is a masterpiece, or very close to it: seeing is believing.

Yes, Hayao Miyazaki won the Oscar with The Boy and the Heron, but can you compare? The fourth feature film and the first animation by the sixty-year-old Spaniard Pablo Berger, Robot Dreams is a masterpiece. Or it comes very close.

I must, briefly, use the first person. Having missed it at Cannes 2023, where it was shown in Special Screenings, once back in Italy I asked for and obtained from a friend a link to watch it. Due to a series of unfortunate coincidences, before it “expired” I only managed to see about a third of it, thirty minutes. Well, that was enough to regret not seeing the whole thing and, even more, to praise it without fear of contradiction and to spread the word among friends and colleagues: you don’t need to drink an entire bottle, Oscar Wilde said or something like that, to know the wine is good.

In short, Robot Dreams left behind vast nostalgia, a fleeting warmth, the legacy of something both beautiful and good. And it did so, it does so by elevating to an imaginative power a dog-robot union capable of echoing both Jacques Tati and our loves. What lightness, what generosity in that unique partnership, which so much of our gaze, our feeling includes: how can one not only empathize, but identify with the desires, the yearnings of an animal for the machine, and vice versa?

Berger, who had already enchanted with Blancanieves, makes animation a friendly song and proselytizes among both adults and children, gently yet inevitably overwhelmed by the affinities between DOG and ROBOT in 1980s Manhattan – watch out, Basquiat will also make an appearance with canvas under arm.

Miyazaki won, as we said, yet in the title alone, isn’t the dog and robot synergy preferable to the boy and heron? It truly is, starting with the style, where clarity, cleanliness, discipline are promises of happiness: an immanence, we would say, presaging transcendence, transgression, fantasy in power. And what is this immanence, already present in the eponymous graphic novel by Sara Varon from which Berger drew, if not the clear line of the Franco-Belgian school and Hergé’s Tintin, reiterated in the eighties by Serge Clerc, Yves Chaland, and Floc’h.

Berger grabs and perfects the parallel convergences of DOG and ROBOT: tired of being alone, the dog orders and assembles a droid, with Earth, Wind & Fire blessing and deepening the newfound friendship. Unfortunately, it won’t last, and not due to a fading of affection: DOG finds himself forced to abandon – a dog abandoning, eh eh… – ROBOT on the beach, and what will become of them, and what will become of us?

It takes strength to face fragility, and Berger, also a solo screenwriter, is equipped with it: loving fragments, elaborations of absence, mocking fates, heart-wrenching epiphanies are the pieces of this cinephile and human, cynophilic and robotic mosaic, torn from paper, redundantly displayed on screen and delivered to the poetry, of the small, very small things, of always concave minimalism, of always sharp wit.

A beauty, a balm for the soul, a break from the ugliness of the world, and as Earth Wind & Fire’s September wants it “Love was changing the minds of pretenders”. Ah, we haven’t told you, Robot Dreams is almost silent, but you’ll hardly notice, caught as you will be in the brotherhood of images and palpitations. In these troubled and shabby years, animation hasn’t left us to ourselves, no: Michaël Dudok de Wit’s The Red Turtle, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, and Pablo Berger’s Robot Dreams have loved us. They love us.

Cinematografo, April 2, 2024