Barry Lyndon | Review by Michael Dempsey

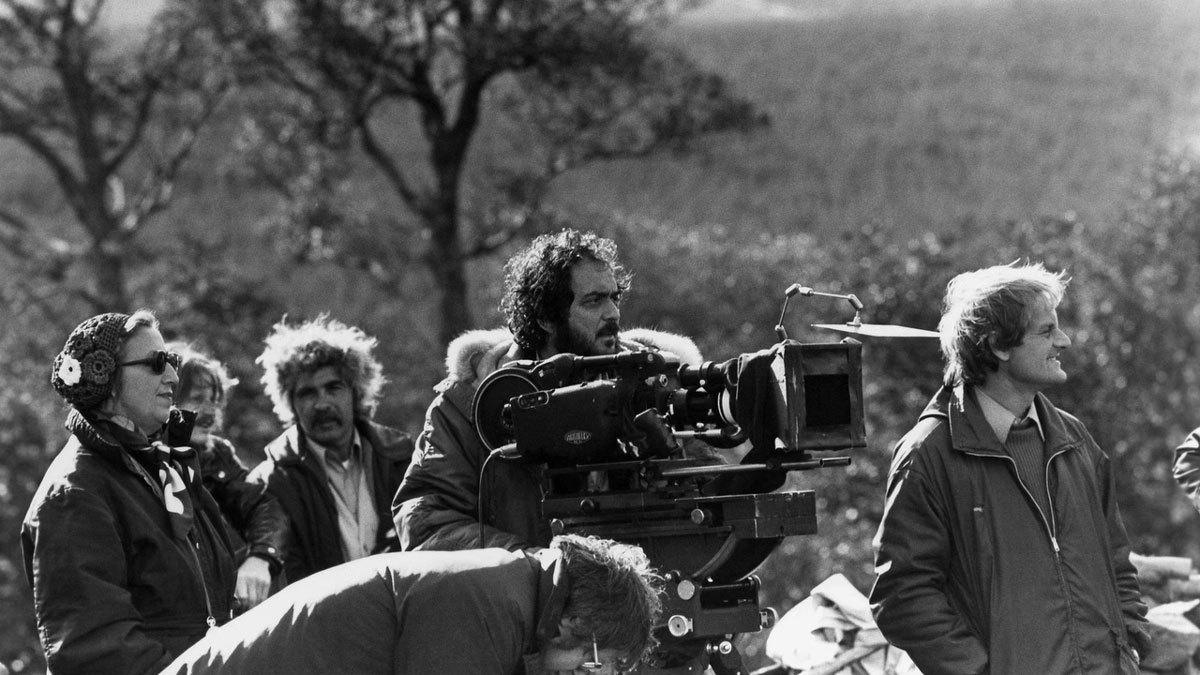

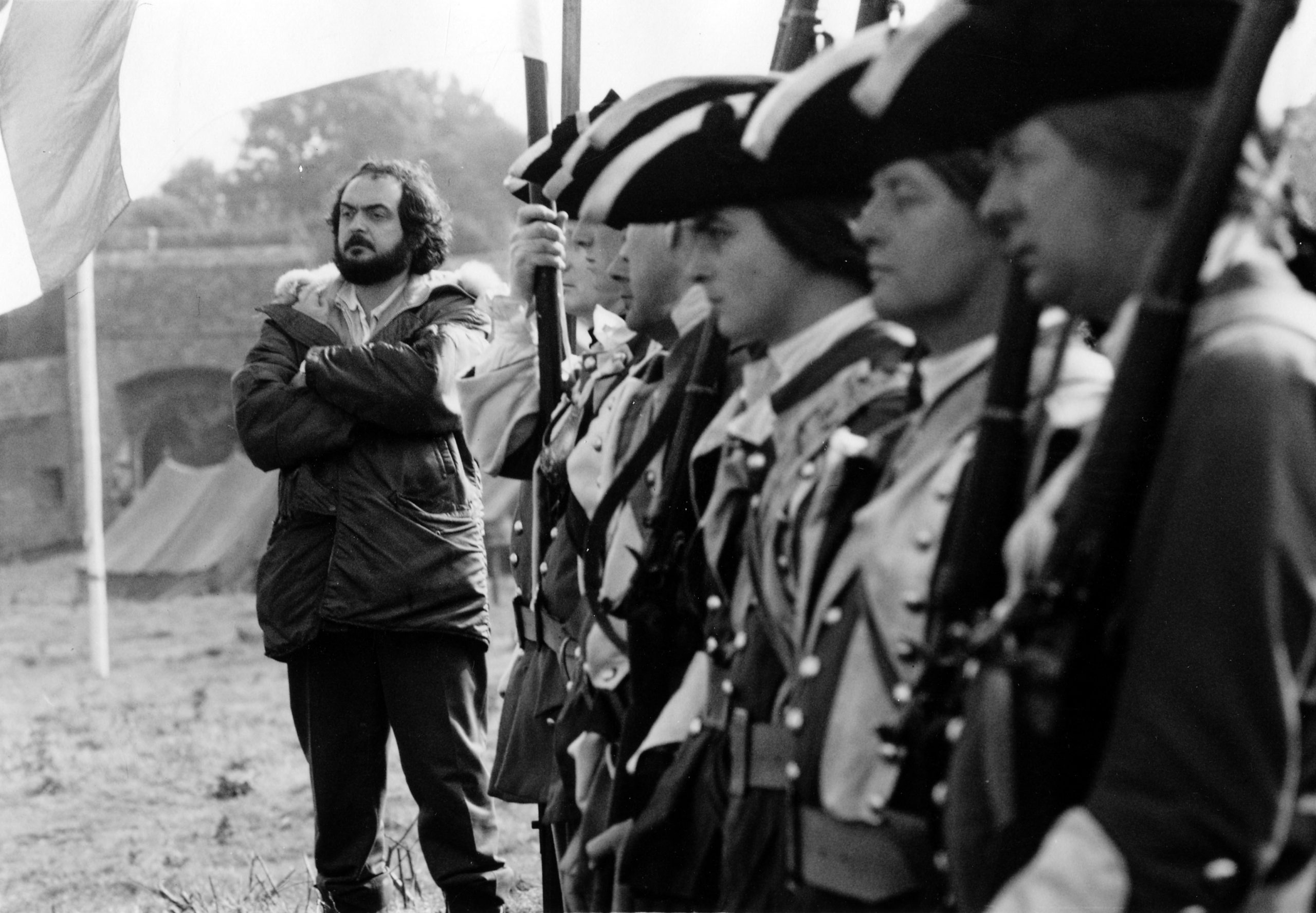

Barry Lyndon is utterly the opposite of the loose, improvised movies which are so popular with many critics these days. Every detail of it is calculated; the film is as formal as a minuet.

Barry Lyndon is utterly the opposite of the loose, improvised movies which are so popular with many critics these days. Every detail of it is calculated; the film is as formal as a minuet.

Beautiful pictures are not film style. Kubrick’s latter-day work is solipsist and smug, isolated and sterile. For me Barry Lyndon is an anti-film, a gorgeous, stultified bore.

Barry Lyndon mette in scena una società violenta, ferocemente classista, dove l’avventuriero gode di una libertà effimera e viene presto emarginato e distrutto. Arricchito dalla più bella fotografia che si sia vista al cinema, il film comunica con stoicismo un sentimento amaro dell’esistenza e della storia.

Since the recognized success of Dr. Strangelove, objections to Kubrick’s obscurity, his enigmatic mind, his bleak view of man, his simplistic view of life, his boring mannerisms abound in the reviews of his films. Barry Lyndon seems destined to encourage the same ambivalent critical reaction.

Barry Lyndon non ha bisogno di chiamarsi Settecento. Se il titolo in Bertolucci indica l’intenzione astratta di definire storicamente quello che – dalla schematica situazione iniziale – si è riproposto come un film dai personaggi classici e «umani»; un film in cui della grandezza e casualità della Storia c’è solo la fluvialità del tempo e l’ampiezza della produzione (la storia economica del film), in Kubrick il nome – come si accennava – deve definire lo sparuto soggetto che è protagonista.

So Barry Lyndon is a failure. So what? How many “successes” have you seen lately that are half as interesting or accomplished, that are worth even ten minutes of thought after leaving them? By my own rough count, a smug little piece of engineering like A Clockwork Orange was worth about five. I’m reminded of what Jonas Mekas wrote about Zazie several years ago: “The fact that the film is a failure means nothing. Didn’t God create a failure, too?”

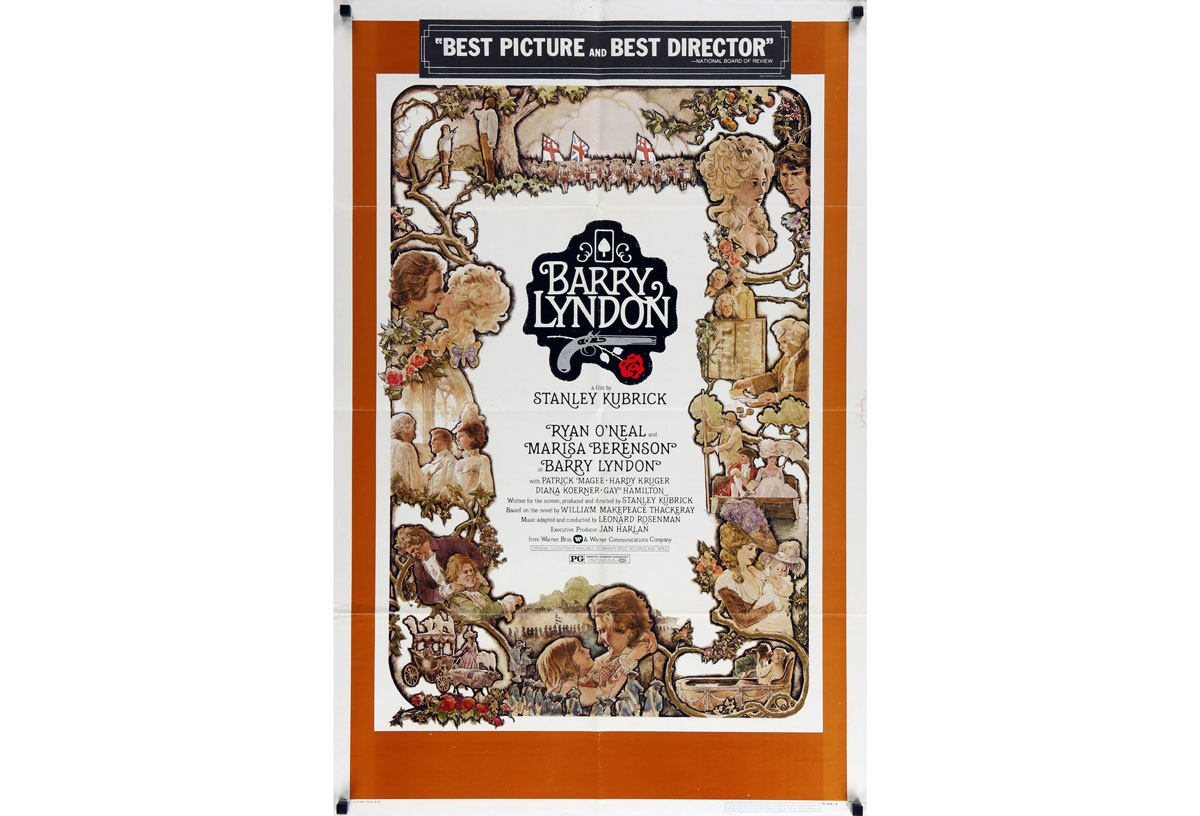

Barry Lyndon is a leisurely, serious, witty, inordinately beautiful, premium-length screen adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s first novel, The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq., published in 1844 and set in the second half of the 18th century.

Barry Lyndon, Stanley Kubrick’s handsome, assured screen adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s first novel, is so long and leisurely, so panoramic in its narrative scope, that it’s as much an environment as it is a conventional film. Its austerity of purpose defines it as a costume movie unlike any other you’ve seen.

Director Benjamin Ross, whose debut feature is The Young Poisoner’s Handbook, celebrates the drama of failure in Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon

Lontano dal cinema di formule e procedimenti a cui rimanda soltanto per la sua mole produttiva, Barry Lyndon si situa in quella zona dove il cinema è invenzione, ricerca, esperimento. Ma dove tutti, coraggiosamente e confusamente, cercano, Stanley Kubrick trova. Non domanda, risponde.

In this essay, Michael Klein elucidates the unique nature of Kubrick’s modernist perspective, as evinced in Barry Lyndon

Barry Lyndon is the loveliest of Stanley Kubrick’s films. Indeed, it’s the one Kubrick movie that could even invite that adjective (or epithet).

Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon, spectacular as it is, flies in the face of an audience’s usual expectations about “costume drama” as a cinematic form of historical fiction.

In this lavishly mounted epic, Stanley Kubrick captures the ghostly ephemerality of a vanishing world with paradoxical immediacy.

In a December 1975 cover story, TIME Magazine examines Barry Lyndon and the many paradoxes of Stanley Kubrick, covering the filmmaker’s Herculean task in bringing the 18th century novel by William Makepeace Thackeray to the screen and the near impossibility of selling a three hour art film spectacle to the masses.

Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon is a lot more than a substitute for an allbutforgotten tale. The movie also translates the printed page into art for the eye and the ear by coordinating the story with the paintings, music and landscaping of the period

![Barry Lyndon [1975] Marisa Berenson as Lady Lyndon](https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Barry-Lyndon-1975-Marisa-Berenson-as-Lady-Lyndon.png)

Dilys Powell review of Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Barry Lyndon’

John Hofsess reviews Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Barry Lyndon’ for The New York Times

An Irish rogue wins the heart of a rich widow and assumes her dead husband’s position in 18th Century aristocracy.

Since the completion of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick has repeatedly suggested that his films are inapplicable to verbal formulations. “I tried to create a visual experience,” he said of 2001 in 1968, “one that bypasses verbalizing pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophical content…

Interview with Director of Photography John Alcott Among all the film-makers of the world, there is no one quite like Stanley Kubrick. To be more

Avvisaglie della fine impossibile di Francesco Cattaneo «…è l’individuo tale quale, elementare e tortuoso, vomitato dal Caos in piena Versailles“. E.M. Cioran (1). «La luce

Recensione di Francesco Bolzoni a Barry Lyndon (1975) di Stanley Kubrick. La recensione è apparsa in «Rivista del Cinematografo», nel 1976

Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon special published by Italian magazine Cineforum n.160, December 1976

![Barry Lyndon [1975] Marisa Berenson as Lady Lyndon](https://scrapsfromtheloft.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Barry-Lyndon-1975-Marisa-Berenson-as-Lady-Lyndon.png)

I doubt if there could be a grander looking film than Stanley Kubrick’s eagerly awaited three hour adaptation of Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon. Stop it at almost any point and you would have something ravishing to look at.

Review of Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, written by Pauline Kael and published in The New Yorker, December 29, 1975

Barry Lyndon (1976) movie review by Penelope Houston, Sight and Sound, Spring 1976

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!