A possible key to interpretation of the style of the work is to consider that Barry Lyndon is not simply a drama with historical background, but is also about history. It can remind us that what we call “history” is a bag of tricks we play upon the dead. As Dr. Samuel Johnson said, “That certain kings reigned, and certain battles were fought, we can depend on as true; but all the colouring, all the philosophy, of history is conjecture.”1 The film seems to echo deliberately the ways that later generations conjecture, viewing and unconsciously altering historical happenings to fit their own conception of what earlier times were like.

In reading the past, we are never satisfied with the fragmentary and incomplete data available in surviving public records, private papers and personal recollections. We use imagination and social judgment to attain a sense of what the people were like who performed the acts we read about. Inevitably we judge them on the basis of our own standards. We go also to surviving cultural artifacts of the earlier time to gain a fuller picture of what life was like for those people: to libraries for their books, to concerts for their music, to museums for their paintings and clothes and articles of daily life, to the streets around us for their homes and public buildings. Unless we are professional historians ourselves, we are apt to be influenced further by generally received scholarly interpretations of a past age that we learned in school. There must inevitably be in our picture of time past some incursion of the outlook and assumptions of our own time.

Finally, as we imagine the people of the past and their way of life, we are apt to use the ways our own memories bring our own past to us: not in chronologically exact recollections of series of events, but in pictures of particularly vivid moments, permeated with our strongest feelings, existing in timeless isolation in memory. One may suggest that Barry Lyndon views the past in this way, with awareness of the distorting lenses of “history.”

To a twentieth-century reader, it is clear that Thackeray’s novel is the eighteenth century viewed through Victorian eyes, recreating some actual people and events of the eighteenth century in a manner that would be agreeable to the later age. The facts from social history are, briefly, that a man named Andrew Stoney was born in 1745 to a family of respectable though rustic gentry with Irish connections. He became a military man in 1763, but soon turned to being a soldier of fortune who lived by gambling and by women. His great coup was to capture the heiress Mary Eleanor Bowes, widow of the ninth Earl of Strathmore, in 1777. To win her, he used subterfuge, and even fought a duel. After marriage he added her name to his own, to become Andrew Stoney Bowes, just as the novel’s Redmond Barry becomes Redmond Barry Lyndon. His wife already had children by the Earl, and in 1782 gave birth to a son by Stoney Bowes. For some years he squandered his wife’s fortune and gradually alienated her by mistreatment. She effected a separation from him in 1785 and a divorce a few years later. Stoney Bowes went to prison for abduction of his wife in 1786, when her tried to force her to return to him. He remained in prison thereafter, for debts he had run up by false use of his wife’s credit, until his death in 1810. All of this factual material, available to Thackeray in printed history and in family recollections of his friend John Bowes, forms the basis for the novel’s events.2

The interpretations and judgments, however, are Thackeray’s as a man of his time. His Barry Lyndon is clearly (to use a Victorian term) a bounder, one who seeks to overleap the settled and venerable bounds of class. Looking back at his past in an autobiographical narrative, this base Irish trespasser shows his shrewdness and quickness of action, but also his ludicrous misinterpretations of his own actions and motives in retrospect. He is a swaggerer soon unmasked to everyone but himself.

For his sense of what eighteenth-century life was like, Thackeray evidently relied almost entirely on works of eighteenth-century literature which were the artifacts most available to him. He gives us the sordid world of criminals and sharpers striving to penetrate the enclave of the upper class, as found in the novels of Smollett and Fielding and the pseudo-autobiographies of Defoe.

He adopts the device found in Swift’s satires, of a first-person narrator unknowingly condemning himself by his own words. Not much in the novel derives from the paintings and music and decor of the earlier period, which is understandable; in a work from a time when museums and musical performances were less generally available than now. Noticeably missing in the book is the sense of stateliness and studied grace in life conveyed by the eighteenth century’s fine arts.

Added from the nineteenth-century outlook on life, instead, are the novel’s romantic dash and pace, and the broad changes of character in the style of Victorian melodrama.3 In some of the editorial asides Thackeray wrote, one finds implied the generally accepted view of Victorian historians: that the eighteenth century was a period of wicked deceitfulness, deplorably lacking in earnestness and sincere morality. Carlyle, for instance, called it “the putrid Eighteenth Century: such an ocean of sordid nothingness, shams and scandalous hypocrisies as never weltered in the world before.”4 Added as a departure from history is the death of Bryan, the little son bom to Barry Lyndon and Lady Lyndon. It serves as a punishment to Barry Lyndon, for his wicked deceitfulness, to lose the only human being besides his mother he genuinely cared for. It also serves to provide the sentimental death scene of a child that Victorian audiences loved. Barry Lyndon remains to the end a self-deluded rascal.

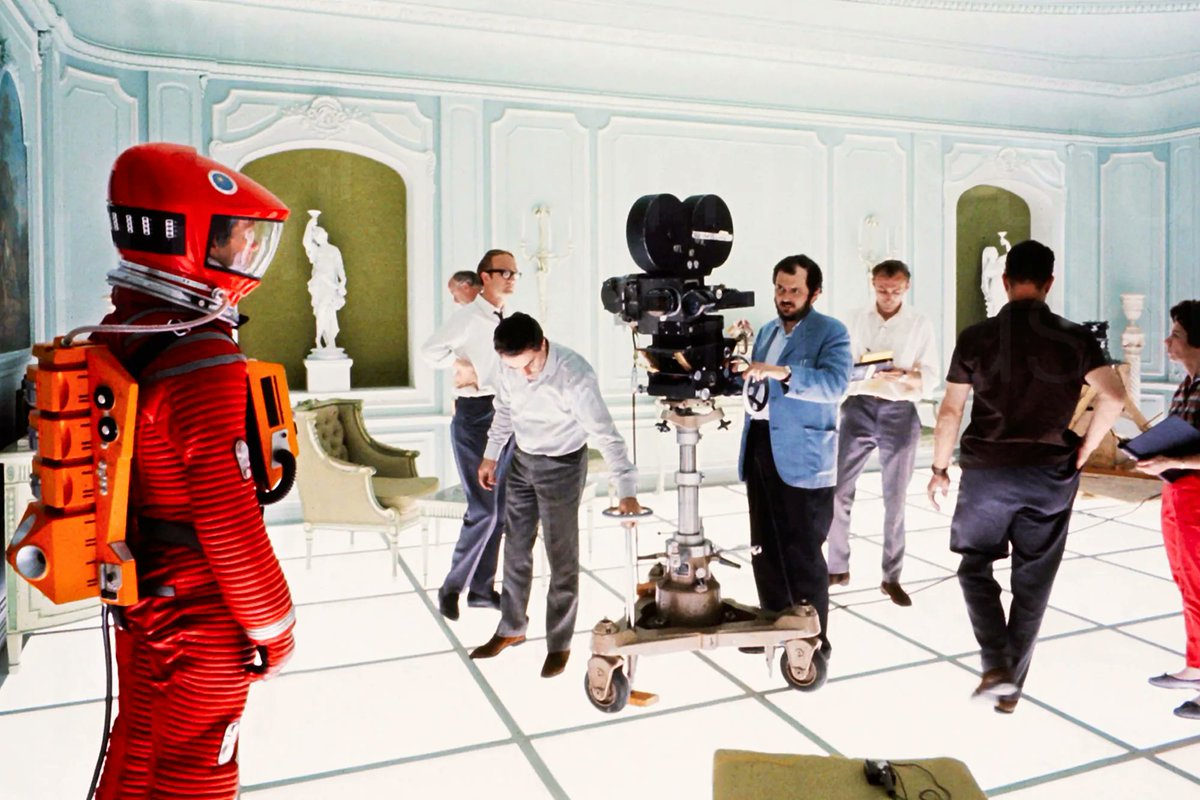

One comes from the novel to Kubrick’s film with a sense of shock. The cinematic version uses the names of the novel’s characters, and the broad outline of their experiences, including the death of Bryan that was Thackeray’s addition to history. But Kubrick’s film makes a reinterpretation of the story, and of its era, from the twentieth-century viewpoint. He brings in a present-day perception of what the eighteenth century was like as a time to be alive. The results are so different that it is hard to view the novel as the “source” for the film.

The film’s hero is an entirely different conception of the original eighteenth-century adventurer. This Barry Lyndon is seen as a social outsider, that favorite figure of twentieth-century literature. He is a disadvantaged young man of the downtrodden Irish, exploited first by the warlords of continental Europe and later by a heartless English establishment that will never admit him to its ranks. This Irish innocent, his simple sincerity shown visually by the perpetual ingenuousness on the face of actor Ryan O’Neal, loses his way among heartless paragons of upper-class stylishness. He tries to assume their fine manners, which mask their cold self-interest. He cannot maintain the air of fashion he assumes, however, and is condemned by upper-class society when he once reveals his strong emotions publicly. He ends crippled and beggared, an outcast on a dole from his elegant and aristocratic wife.

The film’s presentation of what eighteenth-century life was like is dazzling, using visual echoes of the period’s paintings and costumes and decor to an unparalleled degree against a background score taken from music ranging from Handel to the period’s popular airs. It owes much less to the literature of the period. It is the eighteenth century viewed, one might say, by someone who has an extensive collection of recordings of baroque music, has been through enough museums to have a sense of the splendor and grace of the eighteenth century’s portraits and landscapes, but has never read beyond the required eighteenth-century novels on his college reading list.

One has to say, further, that the film’s view of the eighteenth century was not formed in recent decades. It takes the view of the earlier era that was generally accepted during the earlier twentieth century: that the entire period was an Age of Reason when emotions were kept suppressed beneath a glittering surface of wit, and when all manners were as studied as those of Lord Chesterfield. The film presents aristocrats, dressed in the clothes of the 1780’s, as smiling hypocrites whose only allowable emotion in public is witty spite. Lady Lyndon, who in Thackeray’s novel was an overheated vessel of tempestuous emotions, is presented in the film as an elegant fashion doll, whose possible emotions are hidden beneath an inpenetrable crust of style and grace. Seeing the later eighteenth century presented thus on screen is an eerie vision for anyone aware of the writings of historians of recent decades, who have begun to reinterpret the era as an Age of Sensibility when fashionable people made a cult of expressing their emotions and following them out to their finest nuances.5

The film departs both from history and Thackeray on one especially significant point. It moves the story of its adventurer innocent slowly but inexorably toward a climactic duel with pistols between Barry Lyndon and his stepson, Lord Bullingdon. There is no such duel in the novel. In the actual life of Andrew Stoney Bowes, the only duel was one, fought with swords, to win Lady Strathmore. In neither was there the deliberate maiming that the film’s Barry Lyndon suffers at the hands of Lord Bullingdon. The duel is necessary to the film, however, as the final presentation of ritualized, mannerly fighting that runs throughout the film from the first scene of all, which is a depiction of the death of Barry’s father in a duel. Kubrick takes duelling as an emblem of the style of eighteenth-century life.

All through the film, a sharp division exists between honest brawling as an expression of strong feeling, and studied modes of fighting that distance and envenom the process of showing anger and aggression. It is an honest, if naive, feeling that causes young Barry to throw wine in the face of the English officer Quin, his rival for Nora Brady. The duel that follows is a different matter. It is a studied exercise in etiquette, but using pistols that are capable of killing. Furthermore, the duelling process is cynically rigged by Nora’s brothers to protect the wealthy Quin whom they want as a brother-in-law. It is a cheat behind its fine manners. Similarly, the fist fight between Barry and Corporal Toole, when the young innocent joins the British army, is an honest expression of anger on both sides. By contrast, the warfare of the eighteenth-century armies on the Continent is studied and controlled, shown as a matter of two long lines of riflemen advancing stiffly toward each other, dressed in brilliantly-colored uniforms and powdered hair, crumpling silently to the ground when shot.

The film’s Barry is led to realize that in the great world of eighteenth-century Europe, having emotions is a weakness, and showing them leaves one vulnerable to the calculated cleverness of others. If he wants to live as a gentleman rather than a brute soldier, he must learn the cool manners of the time. He tries. He gains his first step to advancement in this world by carefully taking advantage of others’ vulnerability. In a scene created for the film, two officers are bathing naked in a stream. They are engrossed in expressing their love for each other, holding hands and staring into each other’s eyes. Thus Barry is able to steal one officer’s uniform and papers, which give him the necessary disguise for desertion and flight.

He is still an innocent, however, about the deception that may lurk behind polite manners. A Prussian recruiter, Captain Potzdorf, is easily able, with fine manners, to capture him as a deserter and force him into the Purssian army, anc. then into service as a Prussian spy. On beginning this life of calculation and deceit, Barry again reacts emotionally, and finds for once his emotions serve him well. In a rush of feeling against deceiving the distinguished visitor to Prussia whose “servant” he will be, he reveals his true identity to him. Together the two manage to flee Prussia successfully.

Now Barry embarks on a career of living as a gentleman in high society. He enjoys the tutelage of the Chevalier with whom he fled Prussia, who has long supported himself in fashionable life by gambling. As the film presents it, gambling is a mania among upper-class people of the time because it offers them an acceptable way to experience strong feelings. The only other public outlet they have for emotion that the film shows is through playing or listening to music. Social law is that they must be decorous in their duets and trios, and at least pretend to a facade of polite manners and restraint at the gaming table. One sees this in a scene where a young “milord” struggles mightily to keep his poise while contending at cards with Barry. The rosy candle glow of the scene meanwhile suggests visually the intensity of feeling burning inside the young man and all those who look on at the battle of the gamblers. So does the background music repeatedly suggest the power of emotions that are never allowed to surface.

Before long, Barry spots a prize that cold self-interest tells him he can win if he minds his manners. At a fashionable spa he sees a beautiful, wealthy young woman, Lady Lyndon, obviously stagnating in a dull marriage to a feeble old lord. There is opportunity to enrich himself by her, and even to many her if the old man dies. Their courtship is presented as an affair of graceful inertia. They simply sit and gaze at each other like figures by Gainsborough, never wrinkling their satins.

Though the high society of the time considers breach of manners in public, to show strong emotion, an unforgivable social sin, it will, just barely, permit emotion to come out in the form of malice. Old Sir Charles Lyndon thus finally spews out his jealousy of Lady Lyndon’s young lover in this form. He makes a scene at the gaming table one night, speaking to Barry with furious controlled spite. Though everyone looks away politely, all are shocked at the old man, and it is perhaps fortunate for his social position that he forthwith throttles on his own repressed venom and slumps dead.

After the swift marriage of Barry to Lady Lyndon, her son, Lord Bullingdon, enters Barry’s life as one bom to the cold correct manners of his mother and father. The stepson loathes Barry in a frenzy of suppressed jealousy and snobbery, but never allows his feelings to show. His manner finds echo in his tutor, the Reverend Mr. Samuel Runt, a society clergyman who is also devoted to Lady Lyndon. The new Mr. Barry Lyndon simply fails to recognize the depth of implacable dislike for him as an interloper that lurks behind the masks of Bullingdon and his tutor.

His attention is distracted by the outrush of love he feels for the son that is bom to him and Lady Lyndon. He cannot disguise the honest, if doting, partiality he feels for his little Bryan, or the impatience he feels at Bullingdon’s very existence. Barry Lyndon’s doting further enrages Lord Bullingdon, as does the way his stepfather squanders Lady Lyndon’s wealth.

The stepson’s malice breaks out, finally, in a major scene created for the film. Lord Bullingdon leads little Bryan into a musicale that his parents are giving for all the best people. He has given the little boy his own shoes to wear, and comments with witty spite on how well the youngster already fits into them. The meaning is devastatingly clear to Barry Lyndon and to the guests. Barry Lyndon is enraged beyond control, all the more because Bullingdon has used innocent, unknowing, fun-loving Bryan as a deadly weapon against his father. Before the horrified eyes of the fashionable guests, Barry Lyndon bellows and launches a murderous physical attack on his stepson. They crash to the floor in a flurry of silks and gilt chairs. It is social doom for Barry Lyndon’s aspirations to eminence. However honest the feeling, by brawling in his own drawing room, he has done the unpardonable. Thereafter the best people, even his former sponsor, Lord Wend over, brush him away with exquisite politeness. Bullingdon has scored a triumph, though he has to remove himself from the household.

Next the marriage of Barry Lyndon and Lady Lyndon receives a mortal blow with the death of Bryan, all the pair had remaining in common. It is the worse for Barry Lyndon that the death was due to a gift he made Bryan in the heat of heedless love, an incompletely broken horse that threw the little boy. Both father and mother are shown in the film weeping over the death bed, even Lady Lyndon’s poise for once overcome. But at least for the outdoor funeral procession we see Lady Lyndon weeping decorously behind a veil, while Barry Lyndon exposes his distraught countenance to general public view.

Without Bryan, and with his social ambitions forever thwarted, Barry Lyndon finds himself in a brocade-and-porcelain wasteland. The estate goes to ruin while he drinks himself senseless. Nothing his loving old mother, come from Ireland, can do is able to salvage the situation. Furthermore, in trying to economize, she makes a bad error when she dismisses Mr. Runt, Lady Lyndon’s devoted chaplain. Mr. Runt, in deadly quiet, joins forces with Lord Bullingdon to eradicate these Irish boors who have entrapped Lady Lyndon.

Lord Bullingdon is the more moved to act because at this time Lady Lyndon attempts suicide. As an overt expression of emotion which could have made a public scandal, the attempt signals that Lady Lyndon is moving “down” to her husband’s social level. Lord Bullingdon challenges his stepfather to a duel with pistols, and the scene is set for the last mannerly, deadly fight of the film.

By now, Barry Lyndon’s own emotions are all but extinguished by his misfortunes. When the duel takes place, he has not even the spirit to use his superiority in duelling. Ironically, now that it is too late to matter, he has achieved the dull, calm, polite manner that might have allowed him to enter the society the film shows us. Now it is Bullingdon who is seen to have strong emotions: he must vomit, as a vent for the mixture of fear and rage he feels at the encounter, before he can assume control of himself. Barry Lyndon with sad indifference goes through the ritual of firing his shot, but fires into the ground. Bullingdon takes his shot with murderous deliberation, and manages to shatter Barry Lyndon’s leg. He has crippled his stepfather for life, an act of savagery done with exquisite decorum.

At the end of the film, perfect outward calm prevails. The crippled Barry Lyndon and his mother silently take passage in a stagecoach to oblivion. Lord Bullingdon and his mother sit together while she writes the bank drafts that pay her husband to stay far from the gaze of high society. Between this mother and son dead silence prevails also. The upheaval is over. Only in Lady Lyndon’s eyes does a faint spark linger, unreachable, unknowable. We do not see Barry Lyndon’s face at all.

The film is, in its mode of storytelling, what could be called a “tragedy of manners.” During the entire actual eighteenth century, a favorite dramatic form was the comedy of manners. In this, the ways of stylish behavior of the day were examined and their likely consequences explored. A recurrent situation of comedy of manners was that an interloper from the country, outside the world of fashion, intruded on that world and set it on edge by flouting its accepted artifices to the point where they stood in danger of collapse. The interloper might be female, as in Wycherley’s Country Wife, or male, as in the figure of Tony Lumpkin in Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer. Whatever the case, the forthright country figure was brought to successful conformity with the ways of society, and good manners prevailed at the happy ending. But in Barry Lyndon we have an interloper who is not brought into conformity, but is destroyed by the slow uncoiling of hatred beneath fine airs. The forthrightness and sincere emotion of the country innocent are savaged and ground out of existence. The world of fashion prevails at the end, but rather than being validated, it has been exposed as vicious and unworthy for all its surface beauty. Hence the denomination “tragedy of manners.” There was no such cold form in actual eighteenth-century drama—tragedy then was a genre full of ranting speeches of strong emotion. It is something created by the film as part of its reconsideration and reinterpretation of the eighteenth century.

The style of the film, as a further way of conveying the idea of what this period of history was like, partakes of the stately manners of its fashionable characters. There is no cutting away from the mannered walks of characters across large spaces, for the twentieth century’s impatient convenience. Instead, the camera holds for a long take, so that the audience experiences the feeling of lethargy that can accompany pageantry and displays of public magnificence. What close-ups and medium shots there are in the film are as artfully posed as an eighteenth-century portrait. But then, repeatedly, the camera pulls back and back from a scene, to prevent any feeling of intimacy between viewer and character. Instead, by the reverse zoom, the figures of the scene are reduced to minuteness, at a distance that is a visual parallel to the baffling distance that exists between ourselves and figures of the historical past we try to know. Again the pace drags during the pulling back. The fixed, remote scene lingers in our eyes like some moment we recall from our own past, outside time and movement.

The script barely allows the fashionable characters to speak to each other, except in carefully polished and studied statements. Lady Lyndon in particular is notable for her silence, with hardly a dozen lines in the film. The elegance of her appearance is left to say everything for her, and comes into stark contrast with her wordless cries of anguish in the later part of the story. Otherwise, the terseness of the dialogue is as if the script were reminding us of how difficult it is to imagine the private, intimate speech of bygone ages, whose people we can know only through documents and their public papers.

The most fluent speaker of the film is its unseen narrator, who is far removed from the roistering tones of Barry Lyndon’s first-person narration in the Thackeray novel. This narrator has the tone of some historian—dry, calm, studiedly objective. Time and again his voice comes in on some scene of visual beauty or near-explosion of emotion. Its effect is always to reduce the moment to part of a chronicle of long ago. In the Ireland that our eyes see as a rustic Eden at the start of the film, the narrator’s voice enters to classify the Barry family’s social status as “genteel,” and the widowed mother’s conduct such as to “defy slander.” In the long, breathless scene that presents young Barry’s love for Nora, the narrator is heard speaking of the first love that “gushes instinctively from the heart,” in a tone that breathes the tolerant ennui of an elderly historian. After Sir Charles Lyndon’s embittered death, the narrator’s voice is heard blandly reciting the bare facts of his demise, as if quoting from an obituary out of the far past. At the end, when Barry Lyndon and Lady Lyndon have gone their separate shattered ways, the film’s final words are tc remind us that this all happened many years since and that “they are all equal now.” The equality is that of dusty death.

Faced with such formidable barriers to involvement as these points of style present, plus the forbiddingly chilly “tragedy of manners” that has been made of the story, it is no wonder that general audiences have been baffled and repelled by the film Barry Lyndon. It may be true, as L.P. Hartley says, that “the past is a foreign country; they do things differently there”6—but this film rubs our noses in the foreignness, the unbridgeable distance between us and an era departed into the past. The melting beauty of visual scene and musical background cannot prevail against this distance. We glimpse the beauty, but cannot make our way to it, any more than we can surmount the velvet ropes and glass cases and gold frames of a museum to encounter the past first-hand.

One has to conclude that the film was never aimed at the enjoyment of the general audience. It defies the conventions of historical fiction and of “costume drama” in film. It is better to say it was made as an exploration of the ways film can suggest the deceptive distances and changing outlines of “history.” It is an experiment in cinematic form. The film must find its audience among those willing to accept its techniques as a cinematic way of expressing the literary style and tone of histories that can never truly put us in touch with the past. Filmed at a cost of eleven million dollars, it might be called the most expensive experimental film ever made. It is a unique experiment, and likely to remain so.

William Stephenson

East Carolina University

NOTES

1 James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, Ll.D., April 18,1775.

2 See Gordon N. Ray, Thackeray: The Uses of Adversity 1811-1846 (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1955), pp. 339-346.

2601Barry Lyndon

3 For further discussion of this point see Robert Alter, Rogue’s Progress: Studies in the Picaresque Novel, Harvard Studies in Comparative Literature, 26 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1964), p, 117.

4 Thomas Carlyle to Ralph Waldo Emerson, letter of April 8, 1854. Quoted in H.L. Mencken, A New Dictionary of Quotations (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1952), p. 336.

5 A notable example of such reinterpretation is by Northrop Frye, “Toward Defining an Age of Sensibility,” ELH, a Journal of English Literary History, 23 (1956), pp. 144-152.

6 L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1954) “Prologue” [p. 3].

Literature/Film Quarterly Vol. 9, No. 4 (1981), pp. 251-260