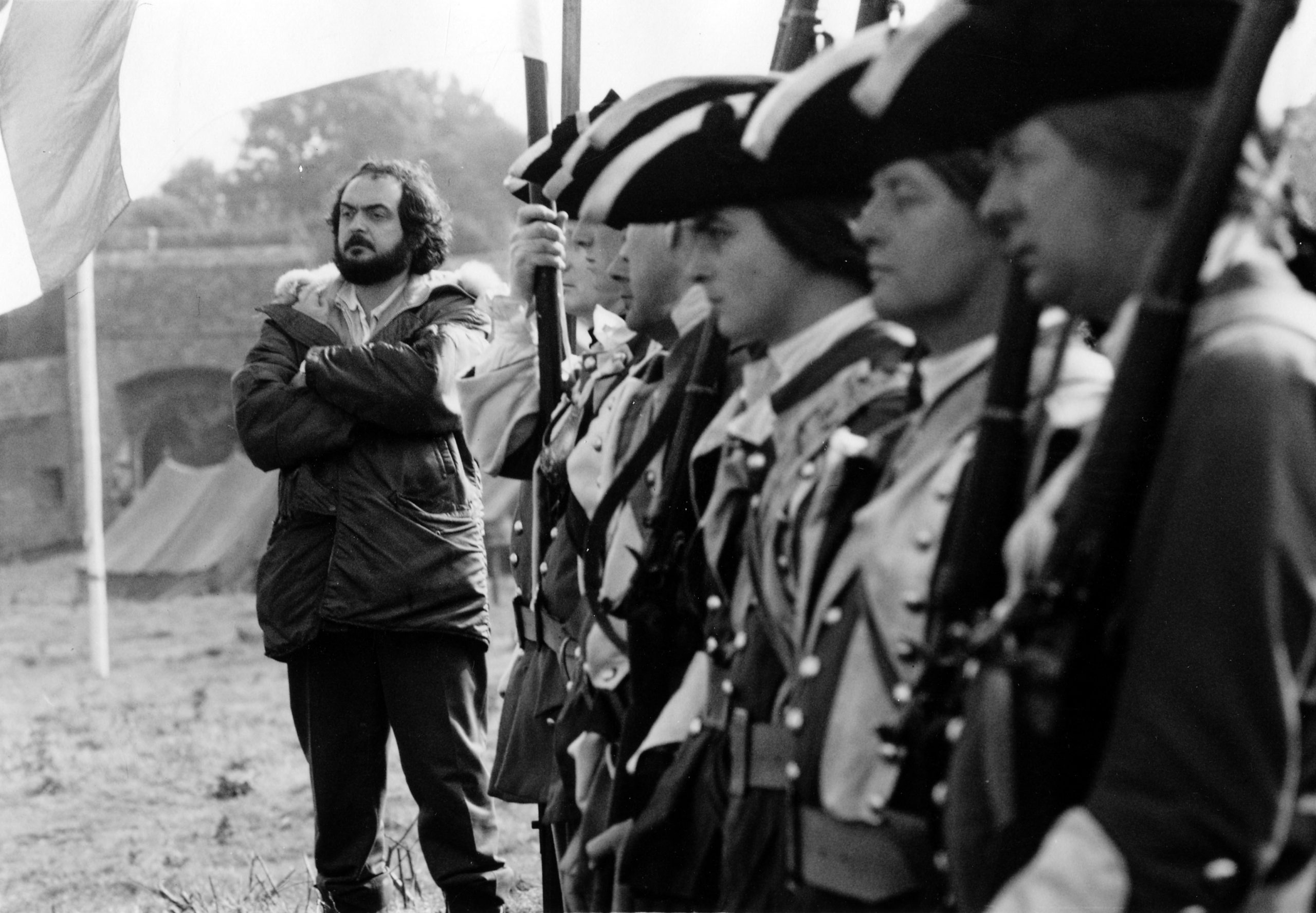

The opening of a new Stanley Kubrick film had become an occasion for Pauline to dread. In the wake of 2001 and A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick had been all but deified by the media; the combination of his reputation as one of filmland’s true intellectuals and his attention-getting ways of making movies had many critics and reporters poised to salute his every effort as a Great Cultural Landmark. The new project was Barry Lyndon, based on Thackeray’s novel about a penniless Irish rogue who rises to dizzying wealth and social position in the mid-eighteenth century. Kubrick’s film moved at a perfect adagio tempo that was nevertheless surprisingly novel and hardly ever dull.

Pauline acknowledged the film’s visually arresting quality and found its first segments mesmerizing. She thought the novel had probably intrigued Kubrick because of its “externalized approach,” which he had devised a way of matching in stately pictorial terms. But she felt he had missed Thackeray’s lighthearted, satirical tone. For her, the movie wore out its welcome fairly soon. “As it becomes apparent that we are to sit and admire the lingering tableaux,” she wrote, “we feel trapped. It’s not merely that Kubrick isn’t releasing the actors’ energies or the story’s exuberance but that he’s deliberately holding the energy level down.” She couldn’t help jabbing Kubrick in a rather personal way when she wrote of her disappointment in seeing the picture’s “slack-faced and phlegmatic” star, Ryan O’Neal, “his face straining with the effort to be what the Master wants—and all that Kubrick wants is to use him as a puppet.” Every frame of it was a reflection of the director’s self-importance. “Kubrick isn’t taking pictures in order to make movies, he’s making movies in order to take pictures,” she wrote. She also expressed her desire that Kubrick “would come home to this country to make movies again, working fast on modern subjects” such as his early, expert noir thriller The Killing.

Barry Lyndon divided the New York critics, ten of whom, led by Time‘s Richard Schickel and The New York Times‘s Vincent Canby, wrote favorably of it, with eight writing unfavorably. There was further divisiveness at that year’s voting for the New York Film Critics Circle Awards, which Rex Reed reported in his column in the Daily News. “I think it is important to remind everyone that Barry Lyndon was the head-on favorite of many of the voters,” he complained, “losing out in the third ballot only because the absentee critics lost their rights to proxies. I was voting for Barry Lyndon all the way.” Reed, like many others, was incensed that Nashville took the Best Picture prize both from the NYFCC and the National Society of Film Critics.

* * *

by Pauline Kael

Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, from Thackeray’s novel, is very deliberate, very smooth—cool pastel landscapes with small figures in the foreground, a stately tour of European high life in the mid-eighteenth century. The images are fastidiously delicate in the inexpressive, peculiarly chilly manner of the English painters of the period, and the film is breathtaking at first as we wait to see what will develop inside the pastoral loveliness. An early bit of sex play between Barry (Ryan O’Neal) and his teasing cousin Nora (Gay Hamilton) is weighted as if the fate of nations hung on it. While we’re still in a puzzled, anticipatory mood, this hushed atmosphere is intriguing, but then we begin to wonder how long it will take for the film to get its motor going. Thackeray wrote a skittish, fast-moving parody of romantic, sentimental writing. It was about the adventures of an Irish knave who used British hypocrisy for leverage; unscrupulous, he was blessed and cursed with too lively an imagination. However, it must have been Barry’s ruthless pursuit of wealth and social position rather than his spirit that attracted Kubrick. The director may also have been drawn to the novel because of its externalized approach; Orwell was describing Thackeray’s gift for farce when he said that one of Thackeray’s heroes was “as flat as an icon.” Kubrick picks up on that flatness for his own purposes and tells the story very formally. After an hour or so, Barry has deserted the British Army, only to be impressed into the Prussian Army and then into service as a police spy in Berlin, and we have begun to long for a few characters as a diversion from the relentless procession of impeccable, museum-piece compositions. All we get is Patrick Magee, encased in the makeup of a noble in the time of George III and wearing an eye patch, as the gambling Irishman that Barry is sent to spy on. The two of them head for the Prussian border, to begin a cardsharp partnership that will keep them travelling, and, with Barry at last a free man, the mood could lighten. It doesn’t. O’Neal looks slack-faced and phlegmatic—exhausted from the effort of not acting—and one gets the feeling that Kubrick is too good for a light mood. Instead, in Spa, Belgium, Barry sets his sights on the rich, walking-doormat countess he will marry, and the film’s color fades ominously to a colder tone. This ice pack, coming at the end of the first half, warns us that in the second half there will be none of the gusto we haven’t had anyway.

As it becomes apparent that we are to sit and admire the lingering tableaux, we feel trapped. It’s not merely that Kubrick isn’t releasing the actors’ energies or the story’s exuberance but that he’s deliberately holding the energy level down. He sets up his shots peerlessly, and can’t let go of them. There are scenes, such as the card-room argument between Barry and the gouty old Sir Charles Lyndon (Frank Middlemass), that just sit there on the screen, obsessively, embarrassingly. Kubrick has worked them out visually, but dramatically they’re hopeless. He has written his own screenplay, and the film lacks the tensions and conflicting temperaments that energized some of his earlier work and gave it jazzy undercurrents. Has he been schooling himself in late Dreyer and Bresson and Rossellini, and is he trying to turn Thackeray’s picaresque entertainment into a religious exercise? His tone here is unexpectedly holy. The dialogue, taken from the book, is too light to support this, so, right from the start, there’s a discrepancy between what the characters are saying and the film’s air of consecration. If you were to cut the jokes and cheerfulness out of the film Tom Jones and run it in slow motion, you’d have something very close to Barry Lyndon. Kubrick has taken a quick-witted story, full of vaudeville turns (Thackeray wrote it as a serial, under the pseudonym George Fitz-Boodle), and he’s controlled it so meticulously that he’s drained the blood out of it. The movie isn’t quite the rise and fall of a flamboyant rakehell. because Kubrick doesn’t believe in funning around. We never actually see Barry have a frisky, high time, and even when he’s still a love-smitten chump, trying to act the gallant and fighting a foolish duel, Kubrick doesn’t want us to take a shine to him. Kubrick disapproves of his protagonist. But it’s more than that. He won’t let Barry come to life, because he’s reaching for a truth that he thinks lies beyond dramatization. And he thinks he can get it by photographing externals.

The film says that all mankind is corrupt. By Kubrick’s insistence that this is a piece of wisdom that must be treated with Jansenist austerity and by his consequent refusal to entertain us, or even to involve us, he has made one of the vainest of all movies. He suppresses most of the active elements that make movies pleasurable; he must believe that his perfectionism about the look and sound of Barry Lyndon is what will make it great. It’s a coffee-table movie; we might as well be at a three-hour slide show for art-history majors.

Ryan O’Neal has worked on his Irish lilt, he knows his lines, he’s all psyched up for the assignment, his face straining with the effort to be what the Master wants—and all that Kubrick wants is to use him as a puppet. As Lady Lyndon, Marisa Berenson is just a doll to hang the lavish costumes on; her hairdos change more often than her expressions. In Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, Malcolm McDowell brought his own vitality and instinct to the bullying hero; here Kubrick manipulates the actors the way he did in 2001. The men are country bumpkins or overbred and ugly (they’re treated rather like the writer—Patrick Magee—in Clockwork); the women, long-necked and high-breasted, are lovely, but they’re no more than the camera’s passing fancies. Kubrick doesn’t want characterizations from the actors. It’s his picture, in the same sense that Fellini‘s pictures have become his. Where Fellini, the caricaturist, hypercharges his people, makes them part of his world by making them grotesque, superabundant. Kubrick, the photographer, turns actors into pieces of furniture.

Even the action sequences in Barry Lyndon aren’t meant to be exciting; they’re meant only to be visually exciting. But when we have no interest in who is fighting a battle, or what the outcome will mean, the action must make an appeal to the senses all by itself, by its graphic strength and visual-emotional movement. It won’t do to have soldiers being moved in patterns just to see what original effects a director can get. When Barry, as a soldier, is in a military skirmish during the Seven Years’ War, Kubrick proves that even a battle can be pastel—the British Army’s red coats are blanched to a photogenic rosy pink. This aestheticizing touch is symbolic of Kubrick’s folly; the soldiers are pink toys—they don’t die, they merely fall over. And this isn’t used for its satiric potential; there’s no comedy in it. The opposing line of soldiers wears lavender-pink cuffs, and that seems to be the reason they’re on the field—so we can see the ravishing pinks and greens. Yet there’s nothing like the extravagant sensuousness of The Leopard. When Barry is wenching, with his arms around two half-naked bawds, the scene is so statically composed that it’s pristine, and when Kubrick looks at the wanly bored Lady Lyndon, palest pink in her bath, and you notice abstractly how her flesh tones blend with the appointments of the bathing salon, all you can say is “Pretty.”

War has its own graphic power; we can turn on the TV and be moved by a combat scene in an old movie even if we don’t know anything about the issues. Obviously, Stanley Kubrick does not have a gift for sensual fury—he’s interested in the contemplative spectacle of war. Yet he’s indifferent to the possibilities in the interaction of images and doesn’t build his sequences by editing—which is how memorable war sequences are made—so his beautiful images are inert. If they seem like slides (certainly the narrator, Michael Hordern, seems like one of those museum tour-guide machines), it’s because they don’t do anything for each other. The episode of Barry’s entrapment by the sly, grinning Prussian officer (Hardy Krüger), which is hammily obvious anyway, is so laborious because Kubrick spells it out instead of making the point by editing. The sequences of the gambling partnership might have been entertaining if they’d been telescoped, like Welles’ account of Charles Foster Kane’s first marriage.

But Kubrick’s mode in this film is oracular and doomy: the narrator tells you what’s going to happen before you see it—you’re even told long in advance that the end is going to be unhappy. The music, off-puttingly classical under the titles (an omen of a consequential film), gets to be enough to make one want to fight back. What with the marches, dirges, and adagios, there’s so much foreboding and afterboding that the music might as well be embalming fluid. Kubrick is doing the opposite of what the revolutionary Russian directors of the late teens and early twenties were attempting: he’s going back to the pageant—to using film as a procession of images. And he’s going back to impressing people by the magnificence of what is photographed; he’s taking pictures of art objects. That antiques-filled room at the end of 2001 must have been where he wanted his own time machine to land. Kubrick seems overwhelmed by the cool splendor of the great manor houses, with their rich interiors and sweeping vistas. The people are repulsively corrupt, but the style in which they live is treated with reverential longing. He simply thinks they’re the wrong people to be living there. The star of the picture is the aristocratic domicile.

The misanthropy is right on the surface. Kubrick makes no attempt to hide it; he thinks too highly of it. The few amiable characters—Captain Grogan (Godfrey Quigley) and the compliant German girl (Diana Koerner)—are dispatched quickly. Kubrick is on a hanging-judge trip. When he lets Barry’s son, Brian, have sparkling, gamin eyes, you can guess that he’s going to kill the kid off and make us suffer. He takes forever over the boy’s dying, though at last, in the deathbed scene. Ryan O’Neal, telling the child a terminal tale, gets his one chance to do a Ryan O’Neal specialty: he smiles through tears marvellously. If Irving Thalberg had hired Antonioni to direct Marie Antoinette, it might have come out like this film—grayish powdered wigs and curdled faces. Some people may go along with it. because it is beautiful—if you like chilly fragility. And since it’s essentially a bloodless, elongated version of a thirties costume picture, it could have a camp appeal. One’s response will probably depend on one’s tolerance for the Kubrick message that people are disgusting but things are lovely. The trend in Kubrick’s work has been toward dehumanization and when Barry and Lady Lyndon have their dry-as-dust courtship and then a wedding that is so lifeless it could be a frozen image. Kubrick seems to have reached his goal: the marriage of robots.

This film is a masterpiece in every insignificant detail. Kubrick isn’t taking pictures in order to make movies, he’s making movies in order to take pictures. Barry Lyndon indicates that Kubrick is thinking through his camera, and that’s not really how good movies get made—though it’s what gives them their dynamism, if a director puts the images together vivifyingly. for an emotional impact. I wish Stanley Kubrick would come home to this country to make movies again, working fast on modern subjects — maybe even doing something tacky, for the hell of it. There was more film art in his early The Killing than there is in Barry Lyndon, and you didn’t feel older when you came out of it. Orwell also said of Thackeray that his characteristic flavor is “the flavor of burlesque, of a world where no one is good and nothing is serious.” For Kubrick, everything has become serious. The way he’s been working, in self-willed isolation, with each film consuming years of anxiety, there’s no ground between masterpiece and failure. And the pressure shows. There must be some reason that, in a film dealing with a licentious man in a licentious time, the only carnality—indeed, the only strong emotion—is in Barry’s brutally caning his stepson. When a director gets to the point where the one emotion he shows is morally and physically ugly, maybe he ought to knock off on the big, inviolable endeavors.

Originally published in The New Yorker, December 29, 1975 Issue

Republished in Pauline Kael, When the Lights Go Down, 1980, pp. 101-105

Read here more reviews by Pauline Kael