2001: A Space Odyssey – Fantastic Journey

Kubrick has, in one big jump, discovered new possibilities for the screen image. He took on a large challenge, and has met it commendably.

Kubrick has, in one big jump, discovered new possibilities for the screen image. He took on a large challenge, and has met it commendably.

The strength of 2001 is that it confronts our civilization with an alien one while preserving the mystery of their encounter. The black monolith appears both as a threat and as a sign of hope at three decisive moments in man’s evolution.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) remains Kubrick’s crowning, confounding achievement. Homeric sci-fi film, conceptual artwork, and dopeheads’ intergalactic joyride, 2001 pushed the envelope of film at a time when Mary Poppins and The Sound of Music ruled the box office.

There is so much talk now about the art of the film that we may be in danger of forgetting that most of the movies we enjoy are not works of art.

2001: Odissea nello spazio abbraccia un arco di oltre un milione d’anni, dall’alba dell’uomo al primo volo verso Giove. Kubrick ha avuto al fianco Arthur C. Clarke, un autore di fantascienza che è anche scienziato, e gli ha chiesto di guidarlo attraverso quelle che una felice formula editoriale ha definito «le meraviglie del possibile».

2001: Odissea nello spazio non somiglia a nessun film di fantascienza o di fantapolitica finora realizzato. Perché non è un film di fantascienza in nessun senso del termine, ma semplicemente un discorso sull’uomo, l’uomo di sempre.

by Bosley Crowther In light of the phenomenal popularity of George Lukas’ 1977 Star Wars, which seems to have done for science fiction movies what

D’avance, nous savions que ce serait un événement. Parce que les dix millions de dollars dépensés garantissaient la qualité du spectacle et nous promettaient ce récital d’effets spéciaux, cette fête de l’imaginaire, ce plongeon dans l’inconnu dont le cinéma de SF nous frustre régulièrement.

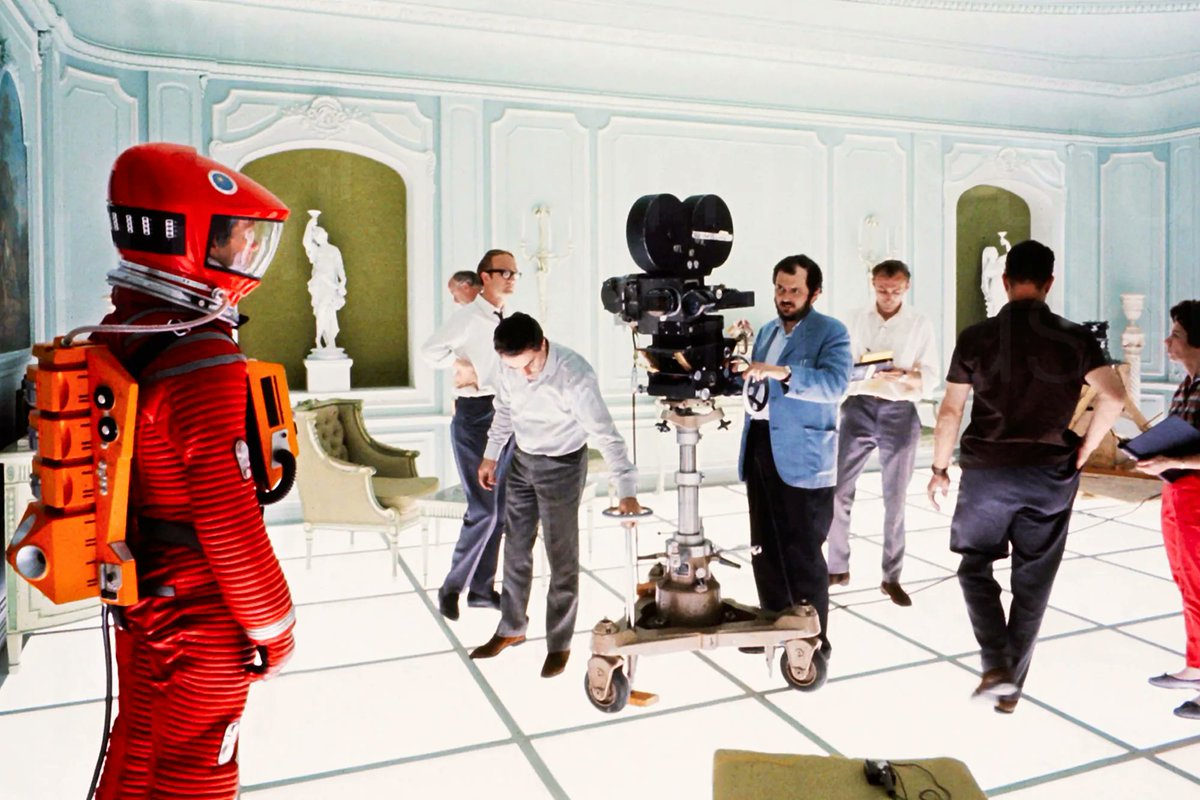

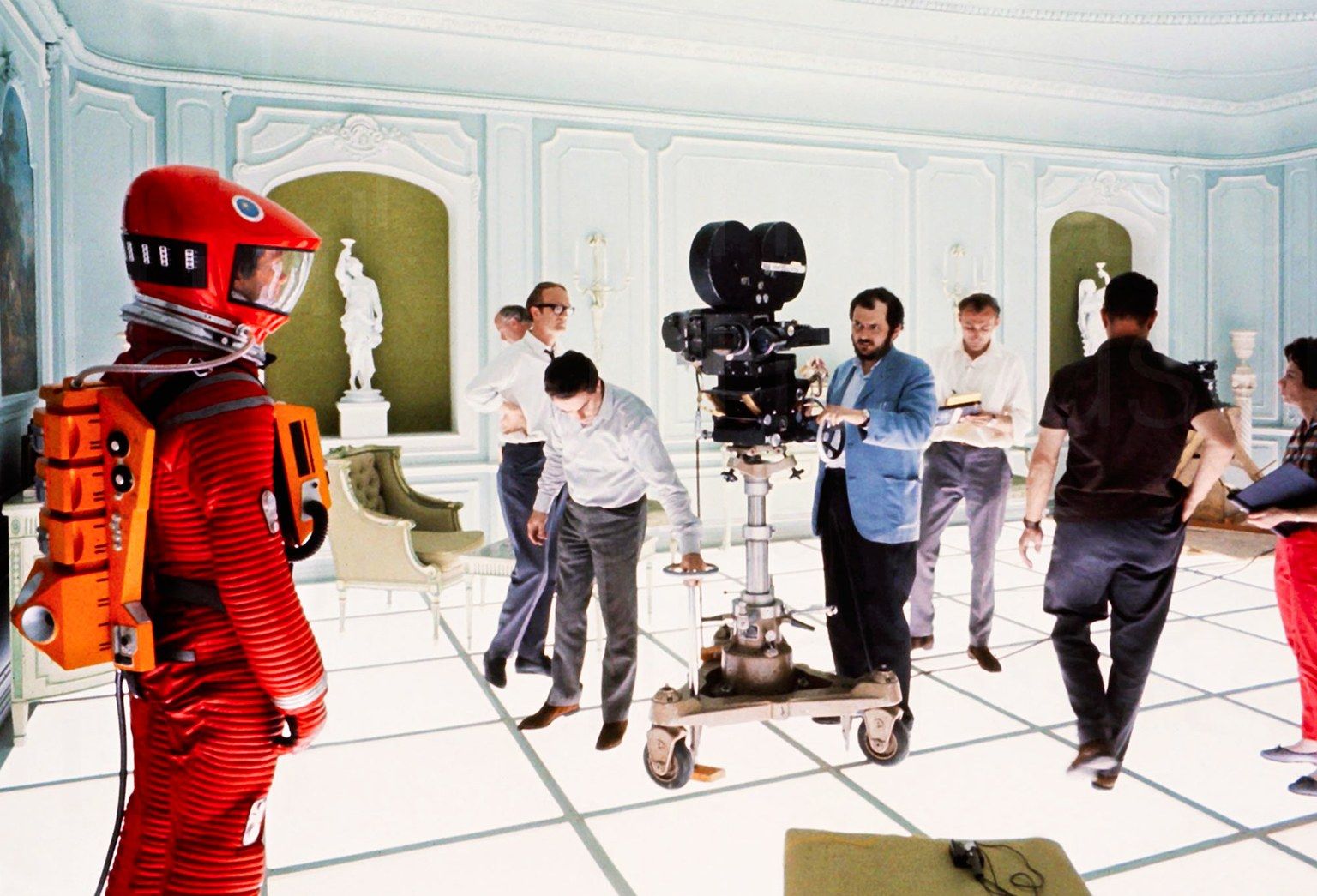

Stanley Kubrick was determined the design for his ‘definitive attempt’ at the science-fiction film should represent a decisive break with Hollywood norms — and who better to enlist to his cause than a pair of spacecraft consultants poached from the very heart of NASA itself?

These are four key scenes from the main sections of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that can be considered, with some reservations, a cinematic milestone in both the technical achievement and in its aesthetic exposition.

Nell’anniversario della morte di Stanley Kubrick, torna nei cinema nella versione restaurata uno dei suoi capolavori, 2001: Odissea nello spazio

2001: A Space Odyssey is fascinating when it concentrates on apes or machines, and dreadful when it deals with the in-betweens: humans. For all its lively visual and mechanical spectacle, this is a kind of space-Spartacus and, more pretentious still, a shaggy God story.

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is remarkable on a number of counts. Firstly, it is perhaps the first multi-million-dollar supercolossal movie since D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance fifty years ago which can genuinely be regarded as the work of one man.

2001 no less than Dr. Strangelove is an apocalyptic vision: it i is an alternate future but no less pessimistic. Beneath its austerely beautiful surface an alarm is sounded for us to examine a problem of which Dr. Strangelove was a pronounced symptom: the possibility that man is as much at the mercy of his own artifacts as ever he was of the forces of nature.

Louise Sweeney, New York-based film critic for The Christian Science Monitor, wrote a generally favorable review following the New York premiere of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Boston staff critic John Allen’s full-page review appeared in the Monitor a month later and M-G-M reprinted it as an ad in a Sunday edition of The New York Times.

Any annoyance over the ending—if indeed it is widely felt—cannot really compromise Kubrick’s epic achievement, his mastery of the techniques of screen sight and screen sound to create impact and illusion.

After we have seen a stewardess walk up a wall and across the ceiling early in the film, we no longer question similar amazements and accept Kubrick’s new world without question. The credibility of the special effects established, we can suspend disbelief, to use a justifiable cliche, and revel in the beauty and imagination of Kubrick/Clarke’s space.

With 2001, we learned the real depth and mass of space, and discovered that “The Ultimate Trip” was going to be a cold, lonely one—an adventure more daunting to the psyche than the body.

Kubrick’s original plan was to open 2001 with a ten-minute prologue (35mm film, black and white) — edited interviews on extraterrestrial possibilities with experts on space, theology, chemistry, biology, astronomy.

Kubrick says that he decided after the first screening of 2001 for M-G-M executives, in Culver City, California, that it wasn’t a good idea to open 2001 with a prologue, and it was eliminated immediately.

We are happy to report, for the benefit of science-fiction buffs—who have long felt that, at its best, science fiction is a splendid medium for conveying the poetry and wonder of science—that there will soon be a movie for them. We have this from none other than the two authors of the movie, which is to be called Journey Beyond the Stars—Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke.

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey took five years and $10 million to make, and it’s easy to see where the time and the money have gone. It’s less easy to understand how, for five years, Kubrick managed to concentrate on his ingenuity and ignore his talent.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!