Now and then a movie project gets, started that involves its makers in a greater outlay of time and energy than was at first envisaged; when the result finally emerges on the screen there is invariably the tendency to wonder if the effort was justified. I suspect this is going to happen in the case of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Kubrick’s last film was the mordant and provoking Dr. Strangelove, released in 1964. We can assume that since then this youngish and remarkably gifted film-maker has been engaged on his cinematic visualization of the first human encounter with what sci-fi writers and addicts call extraterrestrial intelligence, and which some believers in flying saucers and related “sightings” regard firmly as reality.

Kubrick really isn’t that type, however. He is obviously fascinated by current space hardware and projections of future developments in the field. He is also aware of the mathematical possibilities in favor of the supposition that some form of intelligent life exists elsewhere in the charted and uncharted reaches of the universe. And he is far too clever to couch his fantasy in the cliched terms of Hollywood science fiction: monsters, and “things” of one horrible kind or another. He has also had the collaboration of one of the most intelligent writers of science fiction and science fact, Arthur C. Clarke. Between them they first drafted a novel (based on a Clarke short story) detailing the kind of space adventure Kubrick had in mind for his film, and from this they built the screenplay—which, by the way, has been kept under wraps during the long period of production.

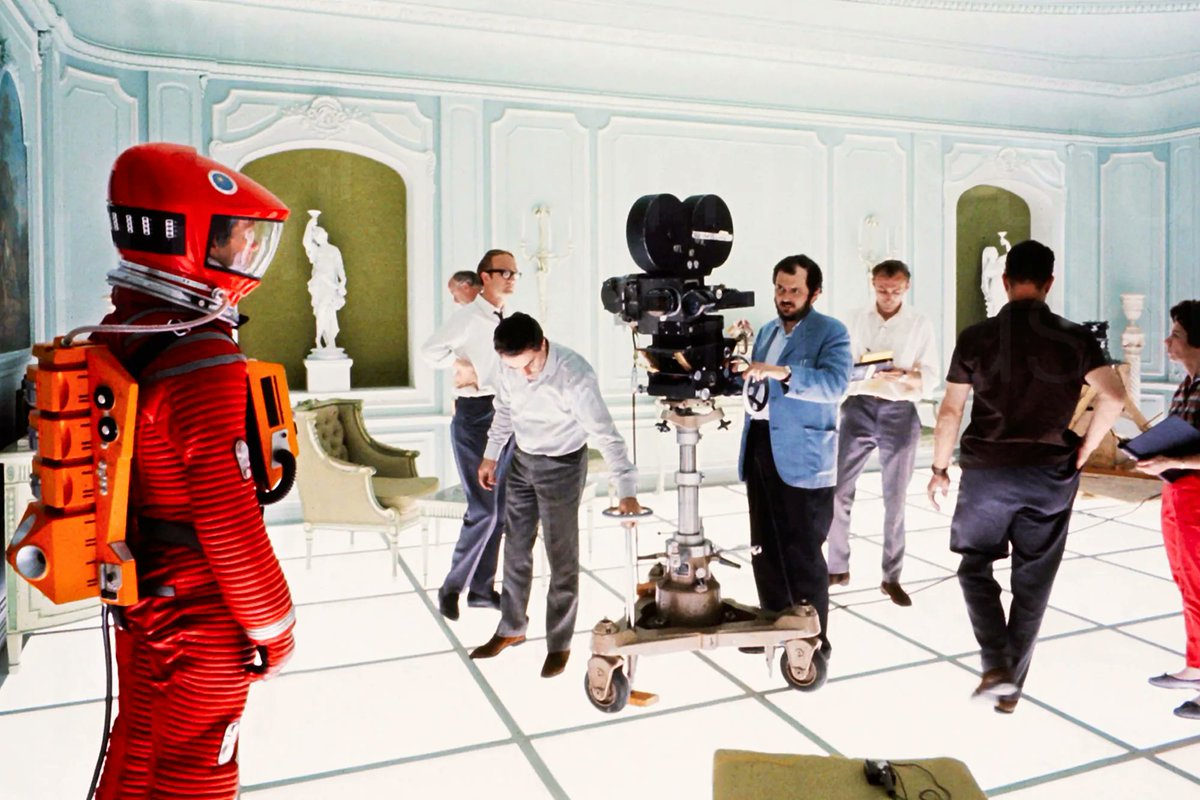

An important part of Kubrick’s plan was to develop new and improved special-effects techniques that would create the illusion of flight in space and that would give audiences the realistic feel of exploring our solar system. A space station, a huge double wheel, revolves at a calculated speed in space to give its occupants a gravitational weight similar to their accustomed one on earth. A space shuttle, run by that familiar firm, Pan American, carries its lone and important passenger to the station, and another vehicle takes him the rest of the way to a landing in an underground moon base. This kind of thing is beautiful, even breathtaking to watch, and somehow Kubrick’s choice of an old-fashioned waltz, “The Blue Danube,” to accompany the space acrobatics gives the right sense of innocent, almost naive scientific adventure that is part of the story scheme at this point.

There is no doubt at all that Kubrick has notably advanced film technique when it comes to achieving perspective for this kind of trickery; how he has done it as yet remains a mystery. Also, for an early section of the film called “The Dawn of Man,” he found a way, through the use of special lenses, transparencies, and mirrored screens, to enact on a sound stage scenes that would have otherwise required a long location sojourn in some desolate place of the world. Conceivably, if other directors are allowed to make use of similar methods, some of the more difficult kinds of location work can be drastically lessened or eliminated altogether—a development many in Hollywood would welcome.

But Kubrick and Clarke had more than mere space adventure in mind. They were concerned with the physical and metaphysical implications of an encounter with some otherworldly form of intelligence, if such were ever to occur. They have certainly been bold and imaginative—more so than any others who have played with the prospect in the film medium—but, as shown on the giant Cinerama screen, the awaited spectacle does come as something of a letdown. Somehow we expected more than we get, and, at the same time, Kubrick puzzles us both by what he does present and by how he presents it.

Intriguing indeed is the use of a monolith—a large slab—as the symbol of an extraterrestrial presence and the key to the story. The slab first appears before a colony of apelike creatures and becomes a sort of “gate” to the knowledge that will allow the development of man as we know him. In essence, the primitive grubbers discover how to make use of a weapon and become carnivorous and thus take the first step toward developing the ability to reach the moon some four million years later. Time 2001 A.D., and now another slab, four million years old, is found buried beneath the moon’s surface, as though someone or something out there knew this would happen. The slab emits an ear-splitting signal which is tracked to the vicinity of Jupiter. Eventually (some two hours of film time later), a third slab is encountered by the lone surviving occupant of a spaceship about to orbit the distant planet. What happens next might cause some moviegoers to wonder if a solution of LSD has been wafted through the air-conditioning system, for the astronaut now, presumably, enters unknown dimensions of time and space not unlike a psychedelic tunnel in the heavens, and lands in—of all possible and impossible places—a kind of translucent Louis-Seize apartment.

The fourth slab appears before the aged astronaut as he lies dying in his splendid isolation, after which, in embryonic form, he floats back through space to twenty-first-century Earth and whatever destiny the viewer might want to imagine. It is this weirdly far-out finale that has a way of putting a strain on the longest section of the film—that dealing with the long Jupiter trip. Aboard are two active astronauts, three others in “hibernaculums,” and an advanced computer that has been programed with human feelings and emotions. Hal, the computer, is there for company and control of the functions of the spacecraft. When Hal begins to make mistakes, as he puts it, matters get pretty sticky for Gary Lockwood and Keir Dullea, the two nonhibernating astronauts.

And for the audience too. Kubrick seems much too fascinated with his intricate and scrupulously detailed, even scientifically plausible space hardware. Those who dote on that sort of thing are going to share Kubrick’s fascination. Others are going to wish for speedier space travel. Then, too, this almost mundanely technical section is poles apart from the wide-ranging fantastics of the final episodes. And, for all the beautiful models, the marvelous constructions, the sensational perspectives, the effort to equate scientific accuracy with imaginative projections, there is a gnawing lack of some genuinely human contact with the participants in the adventure. In fact, most human of all is Hal, the computer, and we feel more concerned with the electronic lobotomy performed on him than with anything that happens to the living and breathing actors. With all the sweep and spectacle, there is a pervading aridity. If people are going to behave like automatons, what happens to them isn’t going to matter much, even if they become privy to metaphysical secrets.

Nevertheless, Kubrick has, in one big jump, discovered new possibilities for the screen image. He took on a large challenge, and has met it commendably. One quibble, though. There are still problems of distortion in that curving Cinerama screen—not of great concern when things are moving fast, but, on the longer takes, definitely an annoyance. Too bad Kubrick didn’t overhaul the Cinerama system while tinkering with everything else.

Saturday Review, April 20, 1968