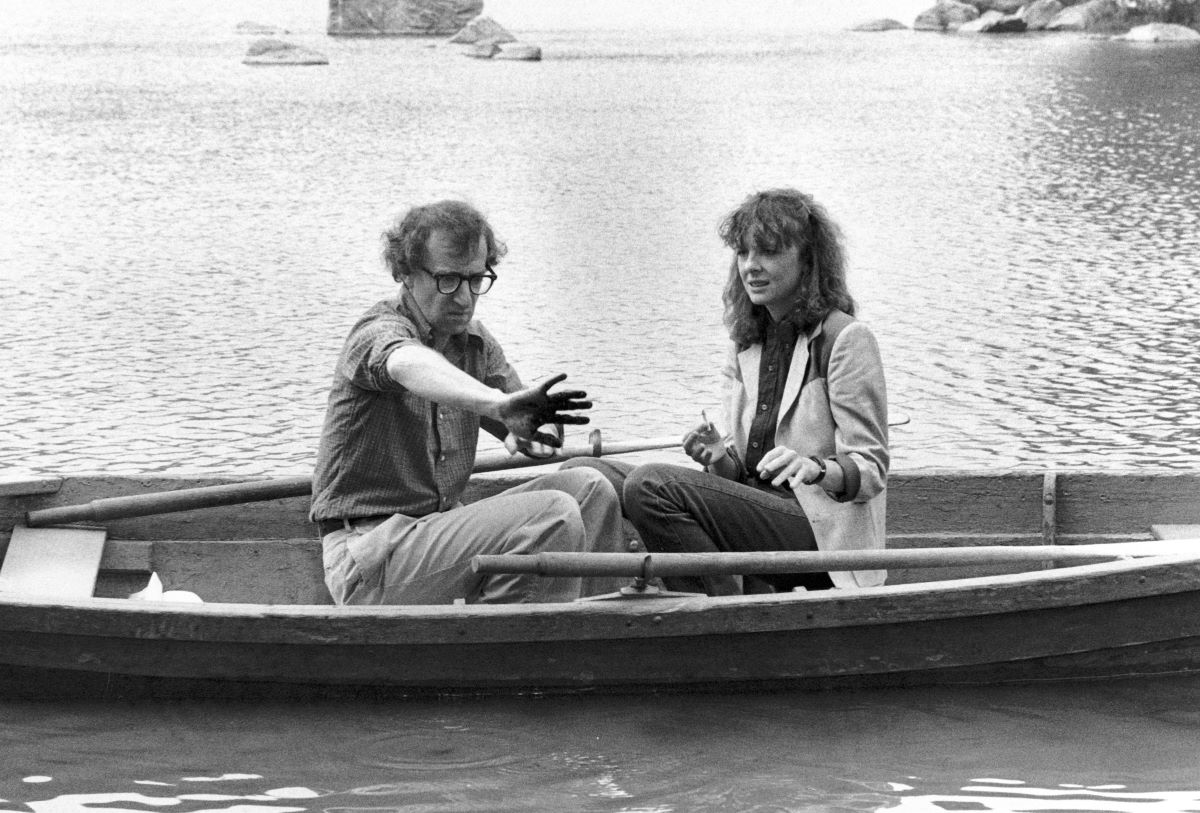

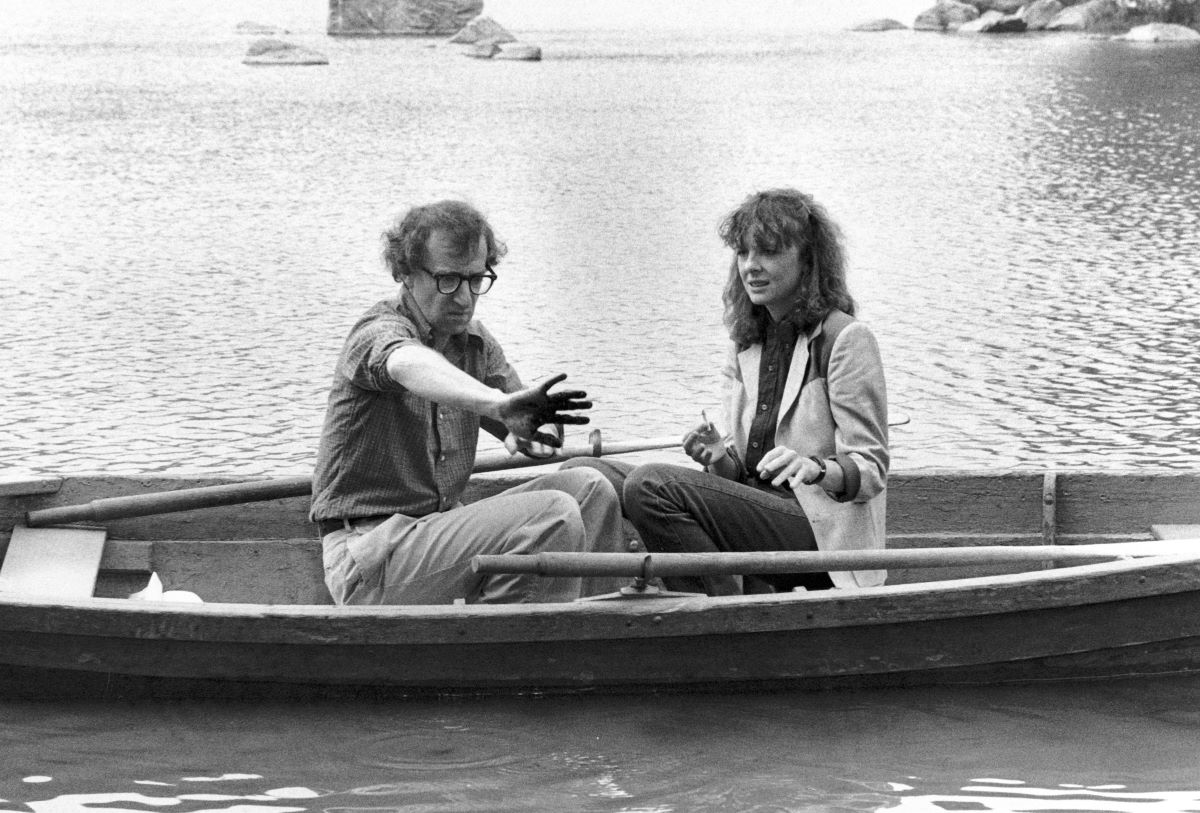

Manhattan (1979) | Review by Stanley Kauffmann

Manhattan is a faulty film, but it’s moderately amusing

Manhattan is a faulty film, but it’s moderately amusing

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalogue is a series of ten films, each one slightly less than an hour long, made for Polish TV in 1988-1989

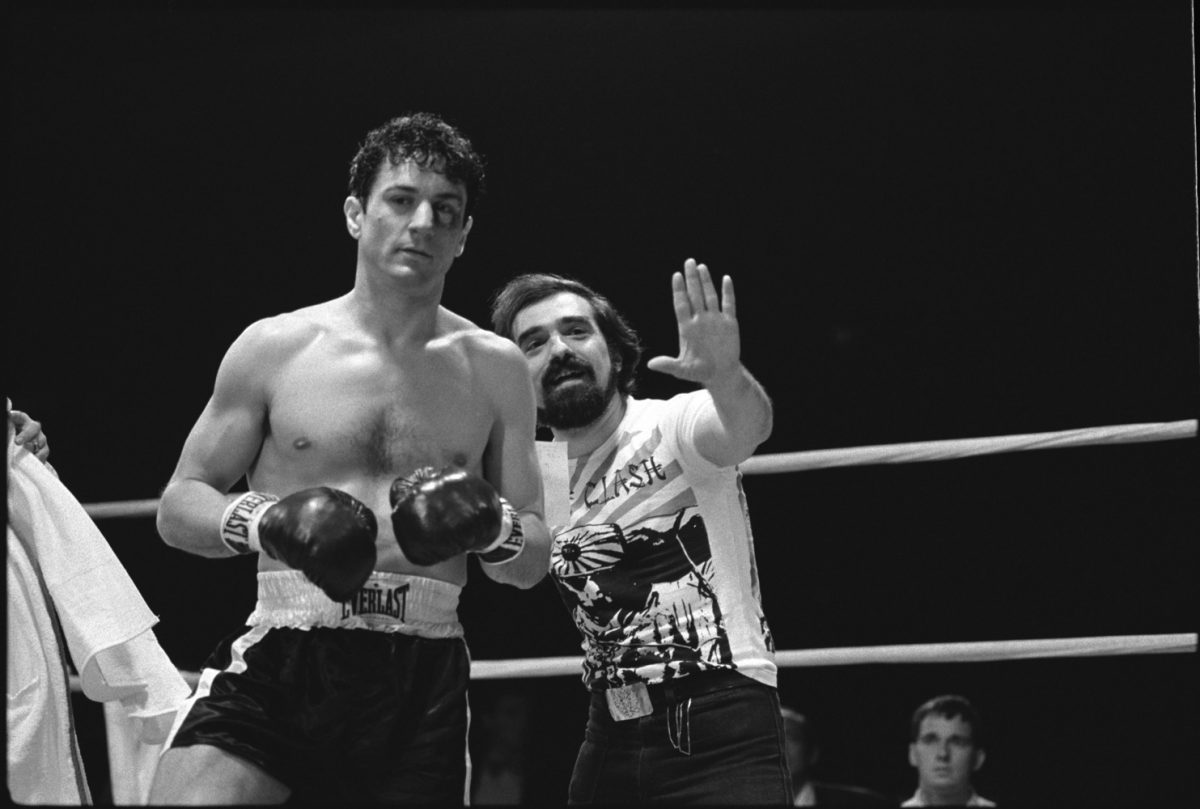

A chief trouble with Martin Scorsese’s new film is that it has to strain to be a Scorsese film. Certain graphic qualities have marked most of his work, and as with any director of personality and style, those qualities had become as natural to him as breathing. But in Bringing Out the Dead, the formerly natural seems forced, redemptive, almost salvaging.

Anyone ignorant of Lynch who sees The Straight Story will need an extra mite of patience to allow its beauty to unfold; others will be curious from the start about why this unconventional filmmaker chose this material, and that curiosity will speed up the unfolding.

This latest Star Wars has the same basic effect as the other three: the sense that it was made not only for children but for the belief in many adults that they are still kids at heart.

Eyes Wide Shut is a catastrophe—in both the popular sense and the classical sense of the end of a tragedy. Everything in Kubrick that had been worming through his career, through his ego, and through his extraordinary talent swells and devours this last film.

Films like Top Gun bring out the pharisee in many of us. We deplore the ethos that these films promote at the same time that, somewhere deep in us, we’re glad that at least some people live by that ethos.

The Piano, garlanded with Cannes Festival prizes, is an overwrought, hollowly symbolic glob of glutinous nonsense

The Sorrow and the Pity is, first, a record. Second, it is a reminder. Third, most important from any view, The Sorrow and the Pity is a fine film.

A radical American journalist becomes involved with the Communist revolution in Russia, and hopes to bring its spirit and idealism to the United States.

The story takes off from the myth that Salieri, the Viennese court Kapellmeister more successful than Mozart yet jealous of him, poisoned the younger man.

To enjoy Blade Runner, you need only disregard, as far as possible, the actors and dialogue. (And the score) The script is another reworking of a threat to humans by humanoids —one more variation on the Invasion of the Body Snatchers theme.

The Shining doesn’t scare. The only pang in it is that it’s another step in Kubrick’s descent.

The picture is virtually bare of Scorsese style, such touches, heavy or helpful, as the opening manhole shot of Taxi Driver or the opening prize-ring sequence of Raging Bull. I saw nothing in The King of Comedy that couldn’t have been done by any competent director. Cinematically, it’s flavorless.

Seeing Martin Scorsese’s new film is like visiting a human zoo. That’s certainly not to say that it’s dull: good zoos are not dull. But the life we watch is stripped to elemental drives, with just enough decor of complexity—especially the heraldry of Catholicism —to underscore how elemental it basically is.

For Stanley Kauffmann, while the film’s thrills did work on him, the frequency eventually irritated him. He criticized the film’s reliance on nostalgia and updating older films instead of innovating new ideas.

When I read three years ago that Vittorio Storaro had been chosen as the cinematographer for Apocalypse Now, I was shocked. Storaro, the lush Vogue-style photographer of Last Tango in Paris and The Conformist, for a picture that was being billed as the definitive epic about Vietnam!

I submit that, if we are going to be moved to thought and action by The Deer Hunter, it ought to be by the implications of its true subject: the limitations for our society of the traditions of male mystique, the hobbling by sentimentality of a community that, after all the horror, still wants the beeriness of “God Bless America” instead of a moral rigor and growth that might help this country.

The Tramp. The Little Fellow. Naturally the obituaries were full of those terms, full of references to the bowler-hatted, cane-swinging, corner-skidding outsider who had become one of the perdurable icons in the collective mind of the world. All true; still it’s not quite enough. Yes, the Tramp is now a deathless image. Yes, he made us laugh and cry and presumably always will.

Beautiful pictures are not film style. Kubrick’s latter-day work is solipsist and smug, isolated and sterile. For me Barry Lyndon is an anti-film, a gorgeous, stultified bore.

Hurricane Marlon is sweeping the country, and I wish it were more than hot air. A tornado of praise—cover stories and huzzahs—blasts out the news that Brando is giving a marvelous performance as Don Corleone in The Godfather, the lapsed Great Actor has regained himself, and so on. As a Brando-watcher for almost 30 years, I’d like to agree.

Full Metal Jacket betrays Kubrick’s avant-garde admirers.

Accattone lives as a work of narrow but intense vision—a film about viciousness and criminality that evokes compassion. Its style is neorealist: it was made on locations, not in studios, with nonprofessional performers. Sometimes this method makes merely vernacular films, but it gives Accattone a grainy, gripping authenticity.

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey took five years and $10 million to make, and it’s easy to see where the time and the money have gone. It’s less easy to understand how, for five years, Kubrick managed to concentrate on his ingenuity and ignore his talent.

Get the best articles once a week directly to your inbox!