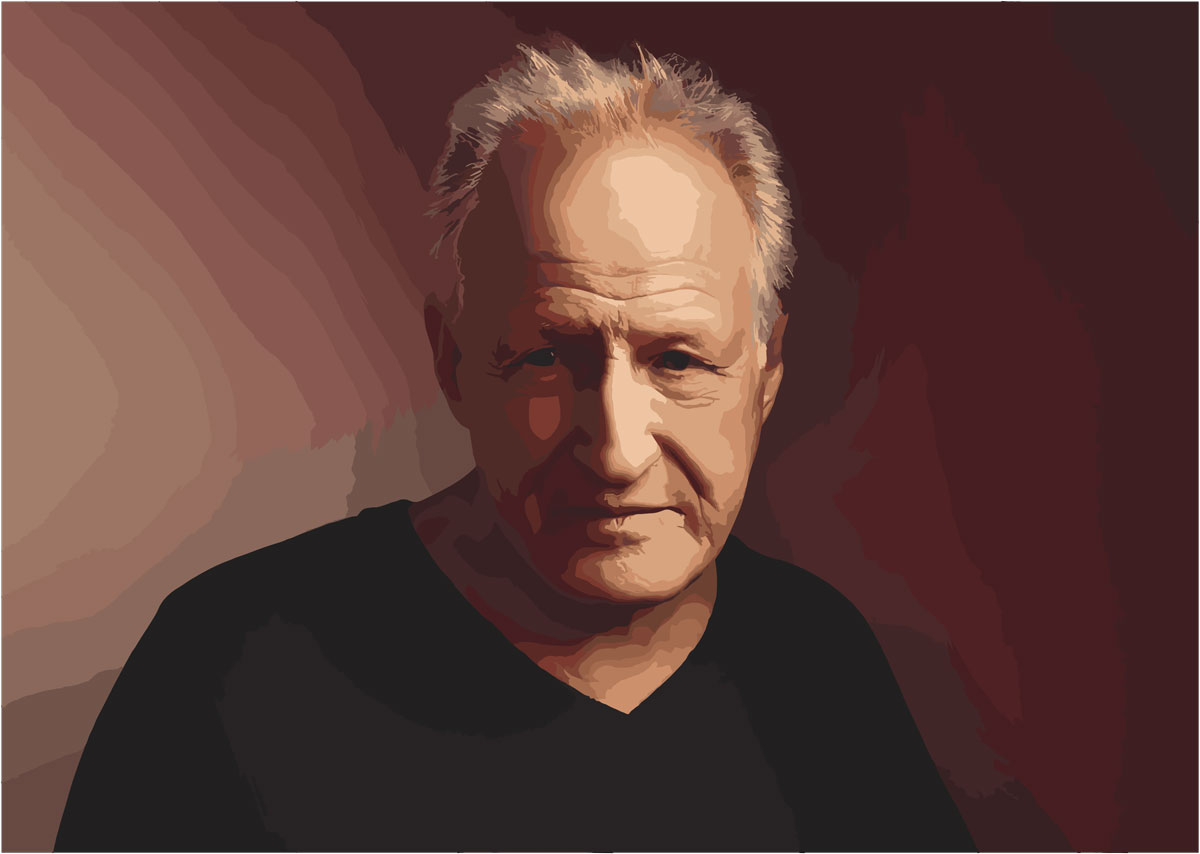

Between reflections and monumental images: starting from his latest film Ferrari, we revisit the romantic and profoundly human cinema of Michael Mann

by Marco Grosoli

The TV series Miami Vice is not just “from” the 80s; it is the 80s. Surface reigns supreme. Everything is image, appearance, style. The luxury outfits, the shimmering sports cars matter more than the fight against crime. Produced by (among others) Michael Mann, a man of the system and anti-system romantic long before 1992, when he adapted the classic of American literary romanticism The Last of the Mohicans (J.F. Cooper, 1826). If everything is surface, what becomes of man? Not just style and visual splendor, Mann’s cinema also restores humanity and greatness to his characters. Pathos, romanticism, lyricism, but also ethics, moral choices. In Thief (1981), every shot is an urban view worth anthologizing, but what hypnotizes us is the rough character of the thief Frank, with superior technique, a tough but beating heart, fighting for independence from the mafia families. Romantically, the individual in search of the absolute against any corporate power. Like the multinationals in The Insider (1999), where drama and action give way to the pure radiance of the aura of two protagonists who, whether winning or losing, always seem to stand on an invisible pedestal. Because Mann’s cinema is made not of individuals, but of mirror-like pairs. In Manhunter (1986), the serial killer and the policeman reflect each other, united in their inability to experience desire except in hallucinated and voyeuristic form: exactly the type of experience Mann makes the viewer have, with the plastic power of his flaming, monumental, hieratic images, amplified by unforgettable musical choices. What separates Pacino and De Niro in Heat (1995), Good and Evil, matters less than what mirror-like connects them: their scrupulous professionalism, the obsessive mania for control. Behind the moral clash, the far more substantial clash between increasingly hypertrophic technology and a world that never lets itself be completely controlled by it. Like the jagged, sprawling, unpredictable Los Angeles of the film. Attention: it’s not that Good and Evil are equivalent. Man is not an infinite game of mirrors in which surfaces reflect only other surfaces. With his orchestration of directing and editing, Mann amplifies the story, and makes sure that the emotion grabs us by the guts. Then we know which side to be on: that of those who recognize their limits. That of the humble but upright taxi driver in Collateral (2004) against the cynical and brash nihilism of his elegant hitman client. That of the moral principles courageously pursued. Words matter, they pierce the surface, indicating the depth of man. Ali (2001): Cassius Clay exposes himself in many arenas outside the ring (the Nation of Islam, the Vietnam War, etc.). He almost disappears behind his kaleidoscopic public image, but no, the man never disappears behind the infinite game of mirrors of the media. Faced with a public image that lives a life of its own, the man Clay reacts, precisely and conflictually, working it on the sides, physically inhabiting the empty space between himself and his myth like Dillinger in Public Enemies (2009). The paroxysmal magniloquence of Mann in singing the glory of Clay is therefore counterbalanced by a strong sense of immediacy and physical presence, dust, eagerness, sweat, thanks to a very mobile 35mm hand-held camera and a bit of digital. After Ali, however, it will emerge that it’s not Mann who was born for digital, but digital that was born for Mann. At the beginning of Blackhat (2015), the internet becomes a tangle of wires and circuits that can be touched. If digital dematerializes the image, Mann finds a grandiose material return for it. He compensates for the two-dimensional flattening with the prodigious detail of high definition. He invents impossible angles to catapult us there, into the heart of the action, without breaking too much the structure of classic Hollywood editing. Thanks to digital, which he masters like no one else (often mixing it with 35 mm), Mann reaches his peak: the 2006 Miami Vice. Everything is merchandise, everything is image. Everything, that is, is immaterial exchange. Of drugs as of data. But we can and must dream of disconnecting from all this, of reaffirming the human being, his ethics, his concrete passions. Even if it’s a love escape to Cuba that lasts as long as a mojito but swells up to coincide with eternity. In Miami Vice, women also begin to split and become active, always a bit neglected by Mann. This is also the case in Ferrari. His hero, obsessed with the seductive and pre-digital materiality of the factory, cars, speed, has nothing romantic about him. Romantic is the film anyway, because it focuses not on love but on its other face: death. It is she who is the real engine of the “Drake’s” success. Before her, Enzo can only bow: before the tomb of his son Dino as before wife and mistress, true protagonists, the only true keepers of death because they are the only keepers of life and its continuity.

FilmTV, n. 50, December 12, 2023

* * *

ORIGINAL ITALIAN ARTICLE:

Tra rispecchiamenti e immagini monumentali: a partire dal suo ultimo Ferrari, ripercorriamo il cinema romantico e umanissimo di Michael Mann

di Marco Grosoli

La serie Miami Vice non è “degli” anni 80: è gli anni 80. Trionfa la superficie. Tutto è immagine, apparenza, stile. Più che la lotta al crimine contano gli outfit di lusso, le luccicanti auto sportive. A produrla fu (anche) Michael Mann, uomo del sistema e romantico antisistema da ben prima del 1992, quando adattò il classico del romanticismo letterario Usa L’ultimo dei Mohicani (J.F. Cooper, 1826). Se tutto è superficie, che ne è dell’uomo? Non solo stile e splendore visivo, il cinema di Mann è anche restituzione di umanità e grandezza ai personaggi. Pathos, romanticismo, lirismo, ma anche etica, scelte morali. In Strade violente (1981), ogni inquadratura è una veduta urbana da antologia, ma a ipnotizzarci è il caratteraccio del ladro Frank, tecnica sopraffina, cuore palpitante ma tosto, che lotta per l’indipendenza dalle famiglie mafiose. Romanticamente, l’individuo alla ricerca dell’assoluto contro qualunque potere corporativo. Come le multinazionali di Insider – Dietro la verità (1999), nel quale dramma e azione cedono il passo al puro rifulgere dell’aura di due protagonisti che, vincenti o perdenti, sembrano sempre ergersi su un piedistallo invisibile. Perché il cinema di Mann è fatto non di individui, ma di coppie speculari. In Manhunter – Frammenti di un omicidio (1986), serial killer e poliziotto si specchiano l’uno nell’altro, uniti dall’incapacità di fare esperienza del desiderio se non in forma allucinata e voyeuristica: esattamente il tipo di esperienza che Mann fa fare allo spettatore, con la potenza plastica delle sue immagini fiammeggianti, monumentali, ieratiche, amplificate da scelte musicali indimenticabili. Ciò che divide Pacino e De Niro in Heat La sfida (1995), Bene e Male, conta meno di ciò che specularmente li unisce: il loro scrupoloso professionalismo, la mania ossessiva del controllo. Dietro lo scontro morale, lo scontro ben più sostanziale tra una tecnologia sempre più ipertrofica e un mondo che da essa non si lascia mai controllare del tutto. Come la frastagliata, tentacolare, imprevedibile Los Angeles del film. Attenzione: non è che Bene e Male si equivalgano. L’uomo non è un gioco di specchi infinito in cui superfici riflettono solo altre superfici. Con la sua orchestrazione registica e di montaggio, Mann amplifica il racconto, e fa sì che l’emozione ci prenda le viscere. Allora sì che sappiamo da che parte stare: quella di chi riconosce i propri limiti. Quella dell’umile ma probo tassista di Collateral (2004) contro il nichilismo cinico e sbruffone dell’elegantissimo sicario suo cliente. Quella dei princìpi morali coraggiosamente perseguiti. Le parole contano, bucano la superficie, indicano lo spessore dell’uomo. Alì (2001): Cassius Clay si espone su tante arene fuori dal ring (la Nation of Islam, la guerra in Vietnam etc.). Quasi scompare dietro la sua caleidoscopica immagine pubblica, e invece no, l’uomo non scompare mai dietro l’infinito gioco di specchi dei media. Messo innanzi a un’immagine pubblica che vive di vita propria, l’uomo Clay reagisce, la precisa conflittualmente, la lavora ai fianchi, abitando fisicamente lo spazio vuoto tra sé e il proprio mito come Dillinger in Nemico pubblico (2009). La parossistica magniloquenza di Mann nel cantare la gloria di Clay viene perciò controbilanciata da un forte senso di immediatezza e presenza fisica, polvere foga sudore, grazie a una mobilissima cinepresa a mano 35 mm e già un pizzico di digitale. Dopo Aì, però, emergerà come non sia Mann a essere nato per il digitale, ma il digitale a essere nato per Mann. All’inizio di Blackhat (2015), internet torna a essere un groviglio di fili e circuiti che si possono toccare. Se il digitale smaterializza l’immagine, Mann gli trova una grandiosa materialità di ritorno. Compensa lo schiacciamento bidimensionale con il prodigioso dettaglio dell’alta definizione. Si inventa angolazioni impossibili per catapultarci lì, nel cuore dell’azione, senza troppo infrangere la struttura del montaggio classico hollywoodiano. Grazie al digitale, che padroneggia come nessuno (spesso mischiandolo al 35 mm), Mann tocca il suo apice: il Miami Vice del 2006. Tutto è merce, tutto è immagine. Tutto, cioè, è scambio immateriale. Di droga come di dati. Ma possiamo e dobbiamo sognare di sganciarci da tutto questo, di riaffermare l’essere umano, la sua etica, le sue passioni concrete. Fosse anche una fuga d’amore a Cuba che dura il tempo di un mojito ma si gonfia fino a coincidere con l’eternità. In Miami Vice cominciano a sdoppiarsi e diventare attive anche le donne, sempre un po’ trascurate da Mann. È così anche in Ferrari. Il suo eroe, ossessionato dalla materialità seducente e pre-digitale della fabbrica, delle automobili, della velocità, di romantico non ha nulla. Romantico è comunque il film, perché incentrato non sull’amore ma sulla sua altra faccia: la morte. È lei il vero motore del successo del “Drake”. Davanti a lei Enzo può solo inchinarsi: davanti alla tomba del figlio Dino come davanti a moglie e amante, vere protagoniste, uniche vere custodi della morte perché uniche custodi della vita e della sua continuità.

FilmTV, n. 50, 12 dicembre 2023