John Boorman’s cult film Deliverance is a rape-revenge movie with a difference. Its haunting power lies in what it tries not to show

by Linda Ruth Williams

There is a contradiction at the heart of the word ‘deliverance’. It is, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, both “The act of setting free, or fact of being set free; liberation, release, rescue” and “The action of giving up; surrender”. It is this double-edged meaning, of liberation and submission, active release and passive acquiescence to bondage, which characterises the uneasy dynamic of John Boorman’s 1972 cult film Deliverance.

Four city men from Atlanta set out to canoe down “the last wild, untamed, unpolluted, unfucked-up river in the south”, led by macho pseudo-philosopher Lewis (Burt Reynolds), whose proclamations on survival in the wilderness provide the narration for the first part of the film. This is a wilderness about to be drowned; the monolithic “power company” we see bulldozing and dynamiting as the credits roll, moving churches and digging up coffins as the film draws to a close, is engaged in a wholesale act of ecological “rape” (as Lewis puts it), damming the river and flooding everything in its wake. The feeling that something is in the process of being lost, that this is a ‘last chance’, pervades the film. Indeed, the poor white trash backwoods folk with whom Lewis and his friends soon clash are themselves on the brink of displacement, if not extinction.

The trip unravels into an antediluvian night-mare of pursuit, as the sinister, ‘genetically deficient’ mountain-men hunt our heroes down river: in the film’s most infamous scene, Bobby (Ned Beatty) is anally raped as Ed (Jon Voight) is forced to look on, only to escape oral rape himself when Lewis kills Bobby’s rapist. Drew (Ronny Cox) then dies in ambiguous circumstances, reappearing later as a horribly twisted corpse; Lewis is badly injured and relinquishes control to Ed, who shoots his (suspected) would-be rapist and hunter with an arrow. The three survivors escape to an unnerving safety built on a cover-up story which disavows not only the double murder they have committed but the shame of male rape and the uneasy circumstances of Drew’s death. Who, then, is delivering what from whom or whom from what? Who or what is being given up, and what is the relationship between surrender and liberation in this most harrowing of films?

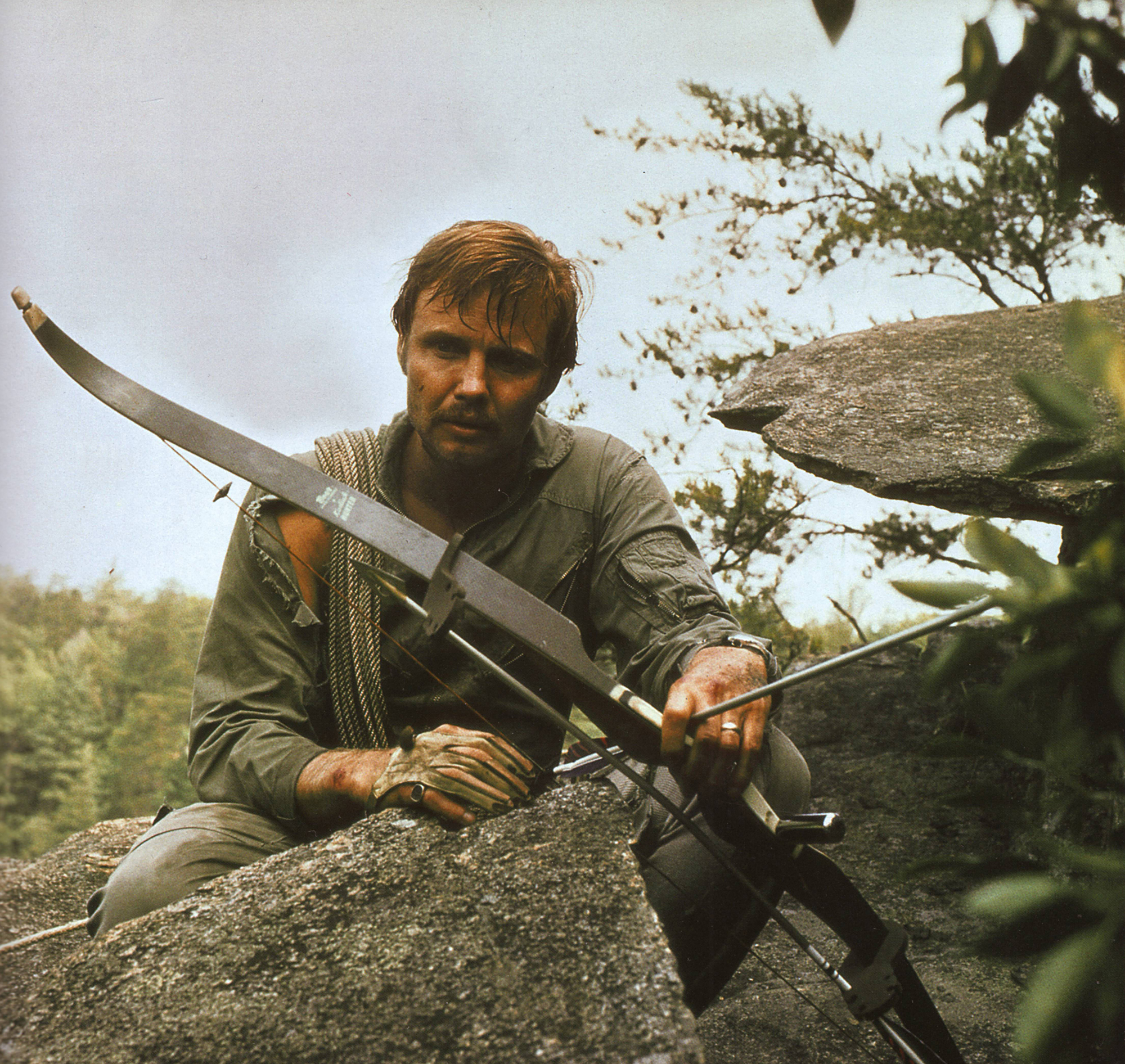

On one level this is a film animated by a pure motive of retribution: it is a rape-revenge story with a difference, the rape being not just man-on-man but country monsters hunting down rich city folk. But in fact nothing here is pure and everything is reversed, since the initial acts of violence can already be seen as retribution, with the country folk getting revenge for the indignities and injustices wreaked upon them by the townies they now have the chance to victimise. As the film opens we are poised on the edge of a monumental natural apocalypse. “You don’t beat it – you don’t beat this river,” says Lewis as he ironically likens their penetration of the river by canoe to that of “the first explorers”, precursors of the power company which is, of course, precisely in the process of “beating” the river. Indeed, theirs is a kind of ‘natural’ sex crime: “we’re gonna rape this Between uncertainty and impotence: Jon Voight as Ed, the witness of ‘Deliverance’, battles with the elements, opposite whole goddamn landscape,” says Lewis, an ecological act akin to the imperial penetration of the Congo in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. It is not just that a sexual crisis happens within a natural landscape, but that what is happening within and to that landscape is itself sexual. For nature in this film, read sex; for relationships between city men and the natural world, a final frontier still left within America, read sexual violence. The river is, conventionally enough, a ‘she’, while the woods are “real deep – inaccessible” – the fantasy mise en scène of a deeply transgressive Grimms fairy tale.

In the middle of all this are the “mountain- men” themselves. They are somehow too close to nature, their home the site of the “rape” of which Lewis speaks, their identity marked and muddied by being ‘too natural’ to be properly human (the “mountain-” prefix qualifies their status as “men”), too intimate with and isolated by the natural (American) landscape to be wholesomely American (an encounter with ‘authentic’ – even redneck – Americana thus poses the question, are the Appalachians as American as the Atlantans?). “There are some people up there that ain’t never seen a town before,” says Lewis at the start, but we (and he) soon find out that nature here is not redeeming; indeed, too much nature is deforming. So natural are these people that they have become unnatural (too natural), but the precise nature of their ‘naturalness’ is characterised not by an idealised authenticity but by something darker. Critics often note the cinematic conventions governing the representation of Deep South country folk – bad teeth, worn dungarees, rusty cars, lazy demeanour appropriate to long hot afternoons lounging on the peeling verandah – as well as their willingness to go one step further as the monstrous hillbillies of horror. Bobby’s opening observation about the detritus of civilisation washed up at their first stop – “Look at the junk, i think this is where everything finishes up. We may just be at the end of the line” – is already laced with threat. Here is the place where everything is lost (and not lost); “no one can find us here,” says Ed later, and no one can hear them scream either.

The horror potential of a country-vs-city clash, charged up by varying degrees and histories of economic exploitation, cultural misunderstanding and sexual threat, has been a rich cinematic resource in the last 30 years or so, well charted by Kim Newman, Carol Clover and others. Straw Dogs (1971), The Hills Have Eyes (1977), Southern Comfort (1981), the Texas Chain Saw Massacre films (1974 onwards), to name only a few, all play with a similar bank of city-meets (and defeats)-country elements. The family too has long been a staple source for horror, as breeding site for psychosis, indulged taboo desires, mutant or demonic children, mostly born cinematically from the late 60s to the mid-70s into the families of urban (and often prosperous) America – Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), Carrie (1976), The Fury (1978), even Eraserhead (1976). The rural family is quite a different matter, a composite monster rendered from recognisable elements of backwoods Americana and the awful suspicion that interbreeding and literal mother- fucking have shredded the vestiges of behavioural control. These are people who might do anything, because they have already done, or been begotten by, the worst possible thing.

In Deliverance country folk are quite simply interbred, bearing the visible cinematic signs of their natural unnaturalness. Uneasy glimpses of bodies which (we assume) wear the symptoms of incest push the film into difficult territory from the start. “All these people are related,” Lewis says after dispatching the rapist, their interconnection entirely undermining the law: “I’ll be goddamned if I’m gonna come back up here and stand trial with this man’s aunt and his uncle, maybe his mom and his daddy sitting in the jury box.” We already know something of this from the half-glimpsed handicapped child watched over by his grandmother, and the visible difference of the albino and strangely androgynous retarded boy with the banjo, striking out the famous “duelling banjos” theme with uncanny dexterity while also challenging us (along with the Atlantan invaders) to make the judgment of sub-humanity. “Talk about genetic deficiencies,” says Bobby, “Ain’t that pitiful?”

So rather than show the consequences of the death or the absence of the family, here the city men become entangled in a sticky, genetically intensified web made by too much family. If the family done right ideally facilitates the smooth path into cultural conformity, the family done wrong breaks open the membrane of civilisation with alarming (and here visually evident) consequences. The unnatural disturbances to human ‘normality’ brought about by an all-too- natural ignorance or defiance of the incest taboo (a defiance which, it seems, all country people live, breathe and breed by) are at work. In a film which is far less graphically horrific than those who last saw it (and were shocked by it) in the 70s might remember it as, perhaps it is this which underpins all that is most unnerving on screen and in implication: an overwhelming sense of relatedness run wild.

Deliverance is often read as a masculinity-in- crisis film, within which these four men, more or less emasculated by city life, have to recover their lost (but not dead) ‘Iron John’ manhood. However, this is not so much a film about men looking for an authentic gender identity as a film about masculinity as an agent of change and difference, something which, far from being fixed, immutable, sovereign, can be lost and precariously found, diminished or warped. Beyond the surface conflicts of ‘men versus the elements’ or ‘civilised masculinity versus the rednecks’, the film is caught up in a protracted encounter between men and their male ‘others’. This is a man’s film in more ways than one (just as it shows that to be a man is rather more than one thing). While family abnormalities underpin all that is wrong here, these are families which keep their women to the margins. Women only creep around the edges and are always seen indoors: from our brief glimpse, ten minutes into the film, of the grandmother seen through the window from Ed’s point of view, to the last 15 minutes, when Ed meets a nurse and Bobby discusses large cucumbers with another old woman, the only ‘real’ woman’s face we see is, fleetingly, a photograph of Ed’s wife, which slips from his fingers as he climbs the cliff face.

Hunting men

As the country family closes ranks, the city family begins to crumble. The woman in the photograph stands with her small son, and both of them are lost when the image falls. In the ‘funeral’ speech Ed gives for Drew, the family is evoked but in a way which underscores the fact that Drew has failed them. Ed stands in the water, embracing Drew’s body as he speaks, staring into nothing (a look Voight perfects in this film). His gaze shifts around as he strains to see the dead person he holds tenderly from behind, and who he is therefore deliberately not looking at (both faces look towards us in the finely balanced frame, one above the other). What Ed sees and doesn’t see is important – his role as visual witness of a number of disturbing images echoes the use of his voice for the first- person narration of James Dickey’s novel Deliverance. In the film, however, the implied authority of this position is lost, and our occasional adoption of Ed’s point of view only undermines our certainty about what we’re seeing, an ambiguity enforced by the film’s colour (or lack of it). The palette of the funeral scene is muted (Boorman’s use of colour desaturation across the film constantly undermines the boundaries between objects), blurring the distinction between Drew’s body and the muddy water into which Ed is to launch him in a parody of a total-immersion baptism. Repeated cuts between Ed embracing the supine Drew and the mute Lewis, now injured, lying in a similar pose in the canoe, suggest that Ed might as well be burying them all. In the middle of all this, one of the few bright objects is Ed’s wedding ring on the hand which holds the rock to which Drew is tied. But just as women and families are evoked as comfort and justification, so they are lost. Ed’s speech underlines the uneasy distinction between presence and absence through its shift from third person to first: “He was a good husband to his wife Linda, and – uh – you were a wonderful father to your boys, Drew, Jimmy and Billy-Ray, and if we come through this I promise to do all I can for them.” Ed is talking to, and looking at, Drew, himself, and nothing – this is as much about the loss of his own family as it is about Drew’s family’s loss of their father.

But it is not just that women are almost entirely absent from Deliverance which suggests that men become less-than or more-than men in certain circumstances. Nor is it simply that in a world without women, men become women (the scenario played out in David Cronenberg’s 1970 film Crimes of the Future), but that marks of sexual identity and difference are set going in a process of mutation, intensified by the incestuous sexual pressure-cooker of the world of the film. Rather than guaranteeing stability or the law here, men only accelerate its breakdown. Far more interesting than the well-intentioned eco-tract this could have been is the anxious essay on identity Deliverance is.

It is in Jon Voight’s character that this theme is most closely focused. Voight’s Ed lies somewhere between the sexual uncertainties of his 1969 Midnight Cowboy role and his embittered, impotent Vietnam vet in the later Coming Home (1978). Other casting also plays with our expectations. In relinquishing his control (and his verbal prowess) half way through the film, Burt Reynolds plays Lewis against type, moving from action-philosopher who is always ‘right’ to wounded and silenced victim. James Dickey, as author of the novel and sole screenwriter credit (and therefore implicated in each side of every conflict represented here), acts on only one side of the law in a cameo role as the country sheriff who appears in the film’s final act. Voight’s characterisation also gestures towards later images in other films. At two points, critical for Ed, Deliverance foreshadows two scenes in The Deer Hunter (1978), when the Robert De Niro character first shoots, then later, at a similar moment, chooses not to shoot, his prey. For De Niro, the second encounter builds on the command and poise of the first, with an even greater sense of self-control, as well as empathy between hunter and deer. In contrast, on the first morning of Deliverance, Ed tracks a deer with bow and arrow, panics, ineptly releases the arrow and cries out in the process, entirely missing his target. It is a clear vignette of weakened masculinity shamefully (rather than violently) out of control; Ed is still very much the feeble advertising man, who has already suggested, at the first sign of danger, that they all “go back to town and play golf”.

Yet the repetition of this scene later in the film does not turn the situation neatly around. By the next morning the men are deep inside their nightmare, and Ed is on the trail of human prey rather than deer. Again, his target is unseeing, again he has it in his sights, and in a crisis of trembling impotence, he cries “release”, shooting his prey but also piercing himself with his own arrow. The sexual scenario played out here is far from subtle, but the way it focuses on the unresolved confusion of Ed’s manhood is interesting. He talks to the corpse, holds its face, plays with its teeth (to check its identity, as the mouth of his would-be rapist), and then is fixed, embracing the body, in a post-coital freeze-frame. A little later, the two men, one dead, one alive, become entangled underwater in a grip which threatens to take Ed down too. The film concludes with Ed’s very inconclusive view, and what kind of maleness we are left with is indeterminate: his nightmare of a flooded landscape, a woman’s voice saying “Go to sleep”. These do not add up to a redeemed, sovereign sexual identity which sits on only one side of the great divide.

The difference which Deliverance delivers is sexual. Alongside the conventional narrative of a fairly classic moral-crisis film (which argues that heroes need to adopt the tactics of monsters in order to defeat monsters, thus becoming monstrous themselves) is a story of men who have lost (or sold) themselves battling with ‘unnatural’ men and only defeating them when they adopt their excessive (and perhaps unmale) forms of masculinity. The pervading sense of sexual infection which crosses the divide between inhabitants and invaders, rural monsters and urban exploiters, rapist and victim, compromises the marked identity of each from the other. It is, then, anxiety which characterises the identity of these men, much more than violence, action or control (the film’s second line, part of the voiceover buddy talk echoed later in Reservoir Dogs, is “Why are you so anxious about this?”) You are, it seems, only as manly as your last manful act, yet even the supposedly manful acts are subject to a number of interpretations.

The world of the film may be almost entirely populated by members of one sex, but paradoxically it is because of this that sexual difference is writ large in every scene. The sodomy scene lays this bare. Ed is tied to a tree by his neck, and must watch as Bobby is stripped. Rather than fighting back, Bobby begs for mercy, an action which is echoed in the scene just described: Ed shoots, but his hillbilly target keeps walking towards him pointing his gun, and though Ed is armed he can only cover his face and cower. “Hey, boy, you look just like a hog,” says Bobby’s assailant, “Go, Piggy – give me a ride.” The scene then goes one step beyond; Bobby moves from human to pig, from male to female, and exactly what kind of sexual assault takes place at the point of his rape is appallingly ambiguous: “Looks like we got us a sow here instead of a boor… I’ll bet you squeal like a pig.” Is this entirely an act between men? How much is the degradation of the scene bound up with the feminisation of the assaulted bodies? “He got a real pretty mouth, ain’t he?” says the second mountain-man, as he moves towards Ed. “You’re gonna do some prayin’ for me boy, and you better pray good” (it is Ed, of course, who then fondles his attacker’s mouth later in the film).

Even though the first perceived violence of the film is forced sodomy between men, the conflict does not shake down clearly into one between heterosexual heroes and homosexual villains. If deliverance is surrender, these are men in part, and on both sides, ‘delivered’ of one kind of masculinity, a suggestion supported by Lewis’ sporadic discourse on loss. Although early in the film he has proclaimed both that he’s “never been lost in [his] life” and that “there’s no risk” (“I don’t believe in insurance,” he says to Ed), he nevertheless continues to counsel a certain kind of macho submission: “sometimes you have to lose yourself before you can find anything.” As Lewis recklessly drives Ed down to the water’s edge, the camera catches their faces behind the windscreen which is itself a blur of reflected, rapidly moving trees; depth of field and colour desaturation minimise the differences between planes and objects, sweeping the men into the foliage.

Assaulting bodies

What, then, has been lost or remembered of Deliverance in the 22 years since its release? While its harrowing power is undeniable, its image as one of the most violent mainstream films of the 70s may now seem odd. Although the film is often remembered as flagrantly vicious, the nasty brother of the nastier Straw Dogs or the much later Southern Comfort, remembering the event like that doesn’t mean that it was like that, or even that there was an event to remember. Nevertheless, a kind of collective forgetting of Bobby’s rape prevailed among critics of the day. For Sight and Sound in the autumn of 1972, “All the Saturday matinee thrills are there”, but nowhere in the review is it mentioned that one of these is sodomy. Similarly the MFB mentions a “sexual assault” almost in passing and only in the synopsis. What is stressed are other forms of violence. Variety, clearly deeply offended and again failing to mention the sodomy, berates the film’s “rhapsodic wallowing in the deadly beauty” of “sudden, violent death”. Yet this is no Peckinpah bloodbath: there are two deaths, the first protracted but unbloody, and a drowned, twisted corpse. The film’s power lies more in what it tries not to show, how it plays with what you saw and didn’t see, what it denies you as well as what it offers up.

The mis-remembering that critics have suffered from is very like something which is going on inside the film itself. If audiences are desperate to bury and forget, this is perhaps because those in the film are too, and it may be that one is a strange effect of the other. Beneath Lewis’ glib philosophising lies a more pervasive discussion of loss, carried out partly through the way the film deals with its own past – and here too masculinity is at stake. The men respond to Bobby’s rape and his rapist’s murder through a process of burial, figurative and actual (“This thing’s gonna be hanging over us the rest of our lives,” says Lewis, and the film could be seen as almost a treatise on the many forms of repression). The positive, active loss which Lewis counsels (and maybe Bobby gets) turns into a communal act of repression: as the dead male body becomes a liability, the camera refuses to cut away from it, instead roving around the four desperate men who plot their next move with the body between them. To ‘lose’ it for good, they dig up the earth with their bare hands, and hide the body in a shallow grave soon to be overtaken by the flood- waters, “Hundreds of feet deep… that’s about as buried as you can get”. At the same time, Bobby is enforcing a burial of his rape (in which Ed is complicit): “I don’t want this getting around.”

Collective disavowal

A more unnerving collective disavowal takes place a little later, following Drew’s death. Along with Ed, we see Drew fall, or throw himself, overboard. When the now-injured Lewis suggests that he was shot, immediately our memory of what we saw (did he fall or was he pushed?) is challenged by the men’s desperate desire to deny suicide and put murder in its place. Even Ed, whose perspective was also ours, can only disavow his memory of the event and say of Lewis, “Of course he’s right – of course.” Most disturbingly of all, when Bobby raises the question of Ed’s victim’s identity further on in the film (“Are you sure that’s him?… It wasn’t just some guy up there hunting?”), Ed replies, “You tell me.” As he speaks, an astonishing thing happens. Turning the corpse’s face towards Bobby, Ed looks away and in the process turns his own face towards us, looking straight to camera and at the audience. The question becomes one for us too, and Ed’s direct address, raised by his look, challenges us to make a response which is impossible. Could we tell him? Do we know what we’ve seen? Can we be sure? Fixed masculine identity, it seems, can no more be read in the face of man than it can be guaranteed by his actions, and we are as lost in these judgments as are those on screen. Perhaps it was something of this which generated those early feelings of horror and shock on the part of viewers also deeply involved in the film’s tensions and conflicts, which ensured that they took away with them something they never actually saw, remembering their own disturbance as if it reflected a visual experience which is rarely there on screen. More significant than this mis-remembering is the anxious forgetting which has taken place, on and off screen.

Sight & Sound, September 1994, Vol. 4 Issue 9