George O’Hare recounts his friendship with Dick Gregory and the events that led to his arrest in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963. Extracts from Confessions of a Recovering Racist, Morgan James Publishing, New York, 2018

Mr. Kelly’s was a nightclub on the Near North Side of Chicago and in those days, you never saw a single Black person in the place—not one. The waitresses were White, the bartender was White, the janitors were White, and the audience, of course, was lily-White. Once in a while, a Black musician like Duke Ellington or Cab Calloway would perform there, but a Black stand-up comedian? Never! I thought of Amos ‘n Andy, and wondered if he was that kind of comedian. Since meeting Dr. King and the Black prison inmates in Father “Dismas”’ program, I no longer found that type of comedy amusing. I began to understand why the NAACP had Amos ‘n Andy taken off the air.

When I arrived at the nightclub, I was greeted by the White doorman. As I walked into the smoke-filled room, all I saw was a sea of White faces at one table after another. The act hadn’t started yet. Taking a table as close to the stage as possible, I ordered a drink and waited.

Finally, a White gentleman came up and took the microphone. After a brief moment of disappointment, I realized he wasn’t the comic; he was only introducing the comic. “Put your hands together for the one and only Dick Gregory,” he said. We politely applauded.

As soon as Dick Gregory took center stage, I recognized this slightly overweight, handsome comedian as the one who entertained the prisoners on Christmas morning of the previous year.

He smoked like a chimney—cigarette after cigarette- as he joked about racism so skillfully that it never occurred to this all-White audience that they were actually laughing at themselves and their racist ways.

“I went to a restaurant down south,” he would say, “and the waitress told me, ‘we don’t serve Negroes,’ and I said, ‘that’s okay, ‘I don’t eat Negroes, give me a half of a chicken.”

Along with his hilarious jokes, he would also depict the not-so-funny reality of what our White ancestors did to other human beings during the slave era. As atrocious as these acts were, his jokes served to temper our shame and give us permission to laugh; not at the cruelty of our ancestors, but at the absurdity of their and our racist mindsets. Unlike a lot of stand-up comedians, Gregory was able to keep his audience in stitches without the use of profanity.

I couldn’t wait to get to Sears the next day to thank my secretary for telling me about that show. When I left work that following evening, I again headed down to Mr. Kelly’s. I wanted to see more of this guy. Maybe he’d repeat the same routine. I wouldn’t have minded seeing it again, but I was pleasantly surprised when he told a whole new set of jokes.

The more I heard from Dick Gregory, the more I wanted to hear. I went back to Mr. Kelly’s the following night and the next night and the night after that. On the fifth night, as I watched Dick Gregory bring his act to a close, I noticed he was looking directly at me. He told the audience how great they were, they applauded and he came straight to my table.

“You’ve been here every night.” He said.

I nodded in agreement.

“Why do you keep coming back?” he asked

“Because I enjoy your jokes and you have new ones every night,” I explained.

After the show he came and sat at my table and we talked until the waiters and bus boys began stacking the chairs on the tables.

“Which way are you going?” Gregory asked.

I told him I was going to the western suburbs. “Can I drop you off somewhere?” I volunteered.

He said he’d appreciate a ride to the L.

As we headed for the “L” station, I thought to myself, Here I am, having a conversation with another intelligent Negro. I had yet to meet one that matched Uncle Lou’s description of a typical Negro. Surely there had to be more regular Negroes than there were exceptions, but at that time I had yet to encounter any typical head-scratching, shuffling, good-for-nothing Negroes.

Gregory wasn’t just exceptional; he was brilliant. He knew something about everything under the sun. He called himself a “conspiracy theorist,” but his theories made a lot of sense. He used to talk about putting on the “magic glasses.” “George,” he once told me, “If you ever put on the magic glasses you’ll see through their propaganda and lies, and you’ll never look at the world the same way again.

One night the conversation was so good I didn’t want to stop when we got to the L, so I took him all the way home. He invited me to his beautifully decorated apartment, eloquently designed with white walls, black furniture, and black rugs. There was some irony in the fact that everything was black and white. I met his wife, Lillian, and his daughter, Michelle, the only child the Gregory’s had at that time.

I cannot emphasize enough how Dick Gregory is the most intelligent, insightful, and genuine person I have ever known. Through those car rides, we developed a real friendship. Here was someone with whom I could be honest and truthful. I asked him so many questions about Negroes he began calling me his “racist friend.” I didn’t take offense because I knew he was right.

The experience of listening to the words of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and seeing up close his love for all people and his commitment to equality brought me close to becoming a “recovering racist.” My friendship with Dick Gregory brought me even closer. I kept going to Mr. Kelly’s or wherever Gregory was playing. Sometimes he’d tell his audience, “Honkies are dumb.” They would laugh, and then he’d say. “If you don’t believe it, look at that man sitting in the back. I call him a racist and he keeps coming back. Stand up “Honkie.” That would be my cue. I’d stand up, and they’d laugh even harder.

He talked about the Constitution, too. “One of these days we’re going to make this Constitution work,” he’d say. “One day we’re going to have a group of White executives talking about ’We have the best and the brightest working for us.’ Then he’ll look over at the door and say, ’Who’s that Negro coming in here?’ Another executive will say, ’Oh, that’s my brother in law.’”

My friends, relatives, and coworkers weren’t the only ones who were concerned about me hanging out in the Black community. I often wondered if Gordon Metcalf had known I would become so involved in the Black community would he have connected me with the Junior Chamber of Commerce or forced me to go see Dr. King speak? By that time, he had become Chairman of the Board of Sears, but I continued to have a good relationship with him.

One day he called me into his office and echoed what everyone else was saying.

“George, you’re ruining your career,” he said, “I know Dick Gregory is a nightclub comedian, but he’s still a Negro, and I can’t understand why you spend so much time with him.

I explained that Dick Gregory took an interest in me and opened my eyes to a whole new perspective of life. “I’d like to bring him down to meet you,” I said.

Mr. Metcalf was open to meeting him, so I invited Dick Gregory to come to Sears. Now, usually, people couldn’t get more than five minutes with the Chairman of the Board, but when I brought Dick Gregory to meet Mr. Metcalf that five-minute rule flew out of the window. In fact, Mr. Metcalf was so impressed with Gregory that he had all of the top management of Sears come to his office to meet him. Gregory spent more than an hour in Metcalfs office mesmerizing those managers with his profound logic and disarming humor.

When I told Gregory I knew Dr. King he said, “Good, maybe you’ll learn something from him.” He already knew Dr. King and knew he believed in the practice of “nonviolence” and “turning the other cheek.” He also knew anyone who became part of Dr. King’s movement had to commit to nonviolence, and Dick Gregory was becoming very much engaged in non-violent practices. Because of Gregory’s anti-Vietnam war stance and his commitment to nonviolence, he even went on a serious fast, stopped eating meat and became a total vegetarian. He convinced me to stop eating meat, and I became a vegan also, for a little while. Eating meat was too deeply embroiled in my heritage to quit for good, but while I was a vegetarian, I went on a fast with Gregory and lost thirty pounds. I changed my bad eating habits a lot because of Greg. I’m not perfect, but I think I’m a healthier eater than a lot of people I know. Sometimes I joke that Gregory encouraged me to become a vegetarian, and at the same time, my love of beer caused me to become a “beer-a-tarian” all by myself.

When one thinks of a nonviolence movement, it generally conjures up visions of everyone peacefully walking, arm-in-arm, singing Kumbaya. That wasn’t the case at all. The nonviolence movement was far from being quiet and peaceful as the name evoked. The marches and demonstrations elicited the worse kind of violence. The thought of how violence underscored the movement was running through my mind the day Dr. King scheduled a march in Marquette Park on the Southwest Side of Chicago. If he had asked me to go to the march, I would have had a hard time saying no, but deep down inside I was terrified at the thought of marching in that racist neighborhood with a group of Black people. Having once shared the racist mindset of my White brothers and sisters, I knew what would be in store for us. The Southwest Side residents would be out there protecting their all-White neighborhoods from those Negroes, just as we used to protect our all-White Chicago beaches from them. Some of the people who would be marching in Marquette Park that day could very well have been some of the White lifeguards from the Oak Street and North Avenue Beaches, all grown up and more embroiled in their racist views than ever. Whenever a Black person would come near our beach, we would shoo them off saying, “Go on N i g g e r! Get out of here!” The hatred that made us want to drown those Black people was the same type of ugly hatred that would cause the racists in Marquette Park to beat, stomp, stone or do whatever they felt was necessary to let the civil rights marchers know they’re not welcome in their neighborhood.

I thought of my friends and neighbors calling me “N i g g e r lover,” and warning me not to hang around “those people.” Befriending a Black person was, in their racist minds, equivalent to an act of treason. Although I understood the necessity of the marches and agreed in principle, I was not prepared to go out there and put my life on the line. I had a wife, I had three sons, and I had a life. Martin must have read my mind.

“George,” he said, “There will probably be a lot of calls coming in, especially from the press. Why don’t you stay here at the church and answer the phones?”

“I’ll be happy to,” I said. I didn’t know if he could detect the relief in my voice. Knowing Martin, he probably could.

Later, when I was at home, and Jean and I were watching the march on TV, I watched, horrified as Dr. King was hit with a brick causing him to fall to one knee. I thought to myself, if it hadn’t been for Dr. King, I might have been the recipient of that brick or something worse.

There were thirty injuries in all that March afternoon, but that didn’t stop Dr. King. He planned another march in Birmingham, Alabama. Dick Gregory went with him, but Dr. King thought it would be best if I stayed in Chicago. Once again, I couldn’t have agreed more. The next evening, I got a call from Dick Gregory.

“Hey George, I’m here in Birmingham.”

“Oh, you’re still there?”

“Yeah, they arrested Dr. King and me, along with some other marchers.”

“Did they let you go?”

“Yeah, they let us all go … to jail.”

“You’ve been arrested?”

“That’s what I said! We’re in the Birmingham Jail. Do you think you can let the newspapers know?”

“I’ll do my best,” I told him.

Since I was the advertising manager for Sears, I knew a lot of media people. They knew I was the one who made the decisions about what ad space to buy for Sears’ advertising, so they were more than accommodating when I wanted to give them a ‘scoop’ for their papers. Some of the media people became more than reporters to me; we became friends. Irv Kupcinet, the legendary columnist for the Chicago Sun-Times newspaper, became one of my closest friends. His “Kup’s Column” was the most widely read and frequently quoted column of any Chicago newspaper. As soon as I finished talking to Dick Gregory, I began dialing Irv Kupcinet’s number. “Hey Kup,” I said, “I’ve got an exclusive for you.” Kup was all ears, and I didn’t disappoint.

“Dr. Martin Luther King and Dick Gregory are in a Birmingham jail,” I told him. Kup wanted all of the details. I did my best to paint a picture for him, based on what Gregory told me.

The next day I bought a Chicago Sun-Times newspaper and turned to Kup’s Column. There was the story, “Dr. Martin Luther King and Dick Gregory were arrested and are in a Birmingham, Alabama jail.” The other newspapers, the Chicago Daily News, the Herald American and the Chicago Tribune, as well as some smaller newspapers, picked up the story. The Sun-Times sent a photographer to Alabama to take a photo of Gregory and Dr. King behind bars. After that, “Kup” became very interested in the Civil Rights Movement. Nearly every day there was a mention of Dr. King or Dick Gregory in “Kup’s Column.”

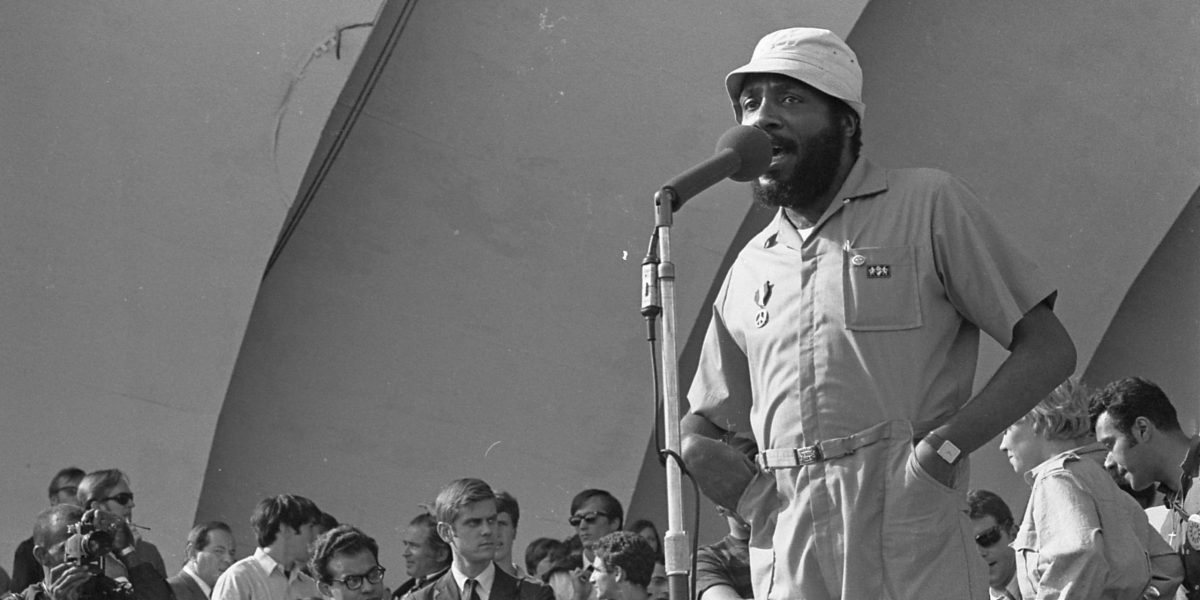

Gregory remained a guest of the Birmingham jail for four days. Why this successful comedian would decide to go to Birmingham, knowing his arrest was inevitable, was a mystery to most people, and Gregory knew it He made a speech at St. John’s Baptist Church to explain why he made the decision, and newspapers across the country quoted him. The Civil Rights Movement became a prominent daily item in the national news, and Dick Gregory was officially a part of that movement.

Membership in most organizations has its privileges. Membership in the controversial Civil Rights Movement had its pitfalls, and for Gregory, that meant immediately losing over 150 nightclub engagements at an average of $20,000 per event. In a matter of days, Gregory went from a sought-after comedian with a multi-million dollar career to being almost on the edge of poverty.

Losing such income didn’t seem to bother Gregory. He was on a mission to bring an end to Jim Crow, racism, the Vietnam War, and worldwide hunger.

* * *

Dick Gregory

Speech at St. John’s Baptist Church

Birmingham, Alabama – May 20, 1963

I’ll tell you one thing, it sure is nice being out of that prison over there. Lot of people asked me when I went back to Chicago last night, they said, “Well how are the Negroes in Birmingham taking it? What did they act like? What did they look like?” I said, “Man, I got off a plane at 10:30, arrived at the motel at 11 and by one o’clock I was in jail.” [laughter] So I know what you all mean when you refer to the good old days. I asked one guy, “What is the ‘good old days’?” and he said, “10 B.C. and 15 B.C.” And I said, “Baby, you’re not that old” and he said, “Nah, I mean 10, 15 years before Bull Connor got here.”

[laughter]

Man they had so many Negroes in jail over there, the day I was there, when you looked out the window and see one of them walking around free, you knew he was a tourist. I got back to Chicago last night and a guy said, “Well how would you describe the prison scene?” and I said, “Baby, just wall to wall us.”

[laughter]

So I don’t know, really, when you stop to think about it. That was some mighty horrible food they were giving us over there. First couple of days, it taste bad and look bad and after that it tasted like home cooking, [laughter] Matter of fact, it got so good the third day it got so good that I asked one of the guards for the recipe.

[laughter]

Of course you know, really, I don’t mind going to jail myself, I just hate to see Martin Luther King in jail. For various reasons: one, when the final day get here, he is going to have a hard time trying to explain to the boss upstairs how he spent more time in jail than he did in the pulpit. [laughter] When I read in the paper in Chicago that they had him in jail on Good Friday, I said that’s good. And I was praying and hoping when they put him in Good Friday they had checked back there Easter Sunday morning and he would have been gone. That would have shook up a lot of people, wouldn’t it?

[laughter]

I don’t know how much faith you have in newspapers, but I read an article in the paper a couple days ago, where the Russians – did you see this, they gave it a lot of space – the Russians claim they found Hitler’s head. Well I want to tell you that’s not true. You want to find Hitler’s head, just look right up above Bull Connor’s shoulders. [laughter] To be honest with you, I don’t know why you call him ‘Bull Connor.’ Just say bull, that’s half of it. Couple of them hep sisters over there in the corner.

I don’t know, when you stop and think about it, I guess little by little when you look around, it kind of looks like we’re doing alright. I read in the paper not too long ago, they picked the first Negro astronaut. That shows y ou so much pressure is being put on Washington, these cats just reach back and they trying to pacify us real quickly. A lot of people was happy that they had the first Negro astronaut, well I’ll be honest with you, not myself. I was kind of hoping we’d get a Negro airline pilot first. They didn’t give us a Negro airline pilot; they gave us a Negro astronaut. You realize that we can jump from back of the bus to the moon?

[laughter]

That’s about the size of it. I don’t know why this cat let ’em trick him into volunteering for that space job, they not even ready for a Negro astronaut. You have never heard of no dehydrated pig’s feet.

I never would have let them give me that job, myself. No, I wouldn’t, that’s one job I don’t think I could take. Just my luck, they’d put me in one of them rockets and blast it off, we’d land on Mars somewhere. A cat’d walk up to me with 27 heads, 59 jaws, 19 lips, 47 legs and look at me and say, “I don’t want you marrying my daughter neither.” Oh I’d have to cut him.

So I don’t know, when you stop and think about it, we’re all confused. I’m very confused-I’m married, my wife can’t cook. No, it’s not funny. How do you burn Kool-Aid? [laughter] You know, raising kids today is such a difficult task. These kids are so clever. They’re so hip. My son walked up to me not too long ago, he said, “Daddy, I’m going to run away from home. Call me a cab.” [laughter] I remember when I was a kid, I told my father the same thing, I said, “Pa if you don’t give me a nickel, I’m leaving home.” He said, ” Son I’m not gonna give you one penny and take your brothers with you.” [laughter] I remember when I was a kid, if my parents wanted to punish me, it was simple, they told me, “Get upstairs to your room,” which was a heck of a punishment because there was no upstairs.

[laughter]

And I just found out something not too long ago I didn’t know. You don’t walk into a kid’s room anymore. You have to knock first. My daughter told me, “I’m three years old, I’ve got rights.” What do you mean you have rights? You haven’t even got a job. I said, “Honey, you don’t know how fortunate you are: you have a room by yourself, a bed by yourself.” I said, “Honey, do you realize when I was three years old, so many of us slept in the same bed together, if I went to the washroom in the middle of the night, I had to leave a bookmark so I wouldn’t lose my spot.” [laughter] She said, “Daddy aren’t you happy you’re living with us now?”

[laughter]

Let me tell you about this daughter of mine. Last Christmas Eve night, I walked into my daughter’s room, I said, “Michelle, tonight’s Christmas Eve, it’s 11:30, you’re three years old, go to bed and get ready for Santa Claus.” She said, “I don’t believe in Santa Claus.” I said, “What in the world you mean you don’t believe in Santa Claus and I’m picking up the tab?” She said, “Daddy, I don’t care what you picking up, I don’t believe in Santa Claus.” I said, “Why?” She said “Because you know darn good and well there ain’t no white man coming into our neighborhood after midnight.” [laughter] So you see, we have problems.

I’d like to say, it’s been a pleasure being here. A lot of people wonder, why would I make a decision to go to Greenwood, Mississippi? Why would I make a decision to come to Birmingham? When I lay in my bed at night and I think if America had to go to war tonight, I would be willing to go to any of the four corners of the world; and if I am willing to go and lay on some cold dirt, away from my love ones and my friends and take a chance on losing my life to guarantee some foreigner that I’ve never met equal rights and dignity, I must be able to come down here.

You know it is such a funny thing how the American mind works-and this is white and Negro alike – how many on both sides of the fence say, “Well did he go down for publicity?” One, I don’t need publicity. But the amazing thing is if I had decided to quit show business and join the Peace Corps and go to South Vietnam, nobody would have said anything about publicity. Only when you decide to help us, you get a complaint.

You people here in the South are the most beautiful people alive in the world today. The only person in this number one country in the world, that knows where he’s going and have a purpose, is the Southern Negro – bar none. When you break through and get your freedom and your dignity, then we up North will also break through and get our freedom and our dignity. Because up North we have always been able to use the South as our garbage can. But when you make these white folks put that lid on this garbage can down here, we are going to have to throw our garbage in our own backyard, and it’s going to stink worse than it stinks down here.

[applause]

One of greatest problems the Negro has in America today is that we have never been able to control our image. The man downtown has always controlled our image. He has always told us how we’re supposed to act. He has always told us a n i g g e r know his place-and he don’t mean this, because if we knew our place he wouldn’t have to put all those signs up. [applause] And if you think we know our place, let one of us get $2 uptight on our rent and 50 cents in our pocket and we’ll kick the hinges off them doors downtown to open up.

But we have never been able to control our image. He’s always told us about a Negro crime rate, to the extent that you have finally decided to believe it. This is the bad part about not being able to control your image. I’ve always said, “What Negro crime rate?” Look at it, we not raping three-year-old kids. We haven’t put forty sticks of dynamite in mother’s luggage and blew one of them airplanes out the sky. And I don’t care what they say about us, we’ve never lynched anybody [applause]. So what Negro crime rate? If you want to see a true Negro crime rate, watch television. Look at all them gangster movies, you never see us. Of course now, you can look at TV, week in and week out and look at all those doctor series they have on television and you’d be led to believe a Negro never gets sick.

[laughter]

For some reason, not being able to control our image has made us almost ashamed of us. Because anything he decides to tell us, about us, we believe it, and become ashamed of it. Negro crime rate? Sure, a lot of us get arrested. Why? The answer is right out there in the street, everyday. You got a Southerner out there in the police department that is probably the lowest form of man walking the earth today. Now here’s a man out there, didn’t like you in the first place, now he’s got a gun. What is your crime rate supposed to look like?

They have gotten to the point where they’ve made you ashamed of relief. “Don’t talk to so and so, she’s on ADC.” I was on relief twenty years, back home. It wasn’t funny, but I wasn’t ashamed of it, because had they gave my daddy the type of job he deserved to have, we wouldn’t have needed no relief. And the day this white man – not only in the South, but in America – gives us fair housing, fair jobs, equal schools and the other things the Constitution say we supposed to have, we will relieve him of relief, [applause] Until that day rolls around, let him pay his dues. The check ain’t much, but it’s steady.

And then you read a lot and hear a lot about Negro women with illegitimate kids. Oh this really makes you ashamed. Each time you pick up one of them newspapers, one of them magazines, reading about Negro women with illegitimate kids, check the article out and see who wrote it. Some chick living in a neighborhood where they’ve got abortion credit cards.

Never been able to control our image, all at once we’re ashamed. Talked about us for so long, we started believing it. Talked about our hair for so long, for a hundred years now we’ve been trying to straighten our wig out. Wouldn’t it be wild if you find out one day that we had natural hair and there was something wrong with theirs?

Every time you look around, they’re talking about a Negro with a switchblade to the extent we don’t want to carry switchblades no more. Well I keep me a switchblade. I got a deal going with the white folks, I don’t say nothing about their missiles and they don’t say nothing about my switchblade.

[laughter]

Here’s a man who owns half the missiles in the world and want to talk about my switchblade. I don’t know one Negro in America that manufactures switchblades – now he going to sell me some and then talk about it after I get it.

He made a lot of mistakes and had all you older people been able to figure out the mistakes he made like the younger people figured them out, we would have had this a long time ago.

[applause]

Yep, he made a lot of mistakes. Here’s a man that got over here and didn’t even know how to work segregation. Didn’t even know how prejudice worked. He just wanted to try it. He said, “We got a bunch of them n ig g e r s, let’s try it” and he messed up. ‘Cause any clown knows that if you want to segregate somebody and keep them down forever, you put them up front. They made the great mistake of putting us in the back; we’ve been watching them for 300 years. [applause] Yeah, that was a big mistake they made. We know how dirty they get their underwear, because we wash them for them. They don’t even know if we wear them or not.

They made a couple of mistakes. It is beginning to catch up with them now. One of the biggest mistakes they made, is that white lady. All at once they think all we want is a white lady. And they don’t understand why we want one. It’s their fault. Bufferins can’t advertise Bufferins without one of them white ladies and so we feel we need a white lady to get rid of our headache.

[laughter]

Every year General Motors advertise them Cadillacs with them blonds and know we gonna get one of them cars. Every time I go to the movie, I can’t see none of them pretty little chocolate drops in them dynamite love scenes-show me one of them white ladies. Every time I look at Miss America, I can’t see no Mau Mau queens-show me one of them white ladies. So what am I supposed to watch? But I’ll make a deal with the good white brother, yes, if he let me turn on television and see some of my women advertising some of them products we use so much of, if he let me go to the movie and see some of my folks in some of them good scenes, and if he let me turn on television this year and see seven of us on Miss America to make up, then anytime he see me with a white woman I’ll be holding her for the police.

[laughter]

Again, I’d like to say it is completely and totally my pleasure being here. I don’t know how many of you in the house have kids that was in jail. Four days I was in jail. Had you been there, as I was, walking through, listening, it was really something to be proud of, really something to be proud of. And if something ever happens and you have to do it again, don’t hesitate.

[applause]

Because the only thing we have left now that’s gonna save this whole country and eventually the world is us. He taught us honesty and he forgot how it worked himself. Nothing wrong with that white man downtown-we just have to teach him how to act. He don’t know how to be fair. He don’t know-we’d never complain if he was fair. “Keep me a second-class citizen, but just don’t make me pay first-class taxes. Send me to the worst schools in America, if you must, but when I go downtown to apply for that job, don’t give me the same test you give that white boy.” Now we are going to have to teach him how to be fair and the only thing we have to do it with is ourselves.

This is it, this is all we have. He has all the police, all the dogs; never thought I’d see the day the fireman would turn water on us in summertime and make us hotter, but they did. What these white folks don’t realize is a terrific amount of police brutality that I have witnessed down here, what they fail to realize is when you let a man bend the law and aim it at us, he’ll aim that same law at you.

[applause]

These are the problems that we have. Again, I am as far away from you as Delta Airline is; anytime there is any problem, I will be back. Thank you very much and God bless you.

[applause]

External links:

Dick Gregory in His Own Words: Remembering the Pioneering Comedian and Civil Rights Activist

Democracy Now! featured Dick Gregory in his own words in their 2002 long interview with the comedian.