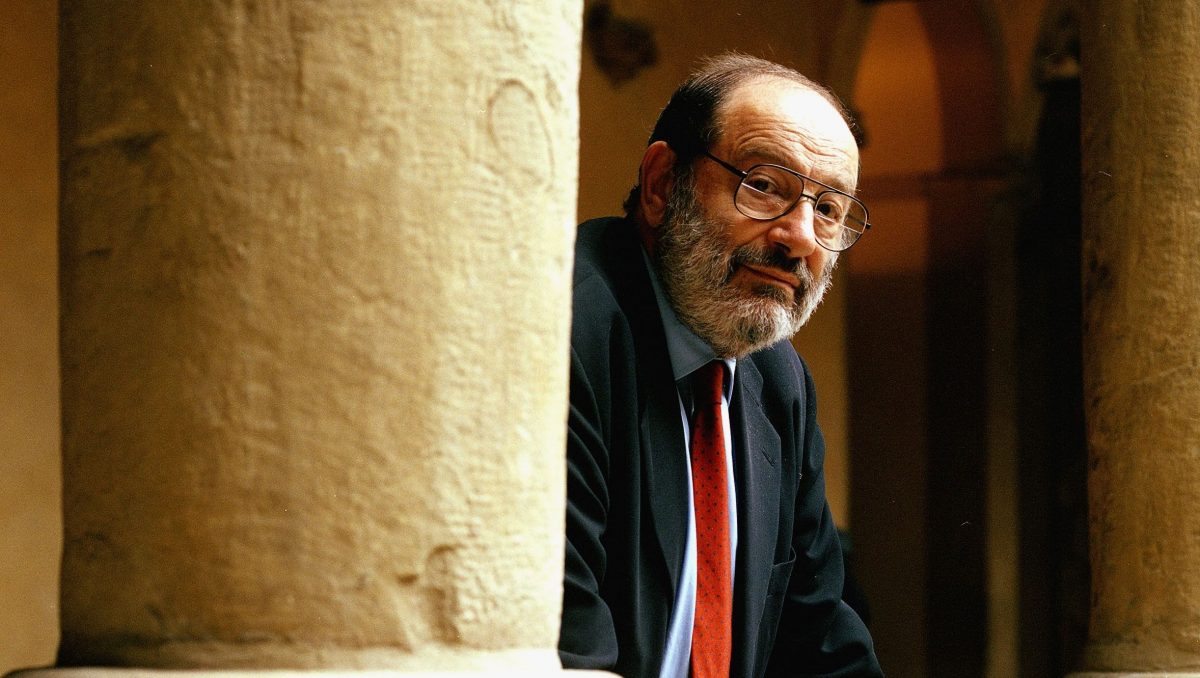

In the following excerpt, originally published in Italian in 1965, Eco offers a detailed examination of the narrative formula that Fleming employed in all the Bond novels, a strategy Eco regards as “the basis of the success of the ‘007’ saga.”

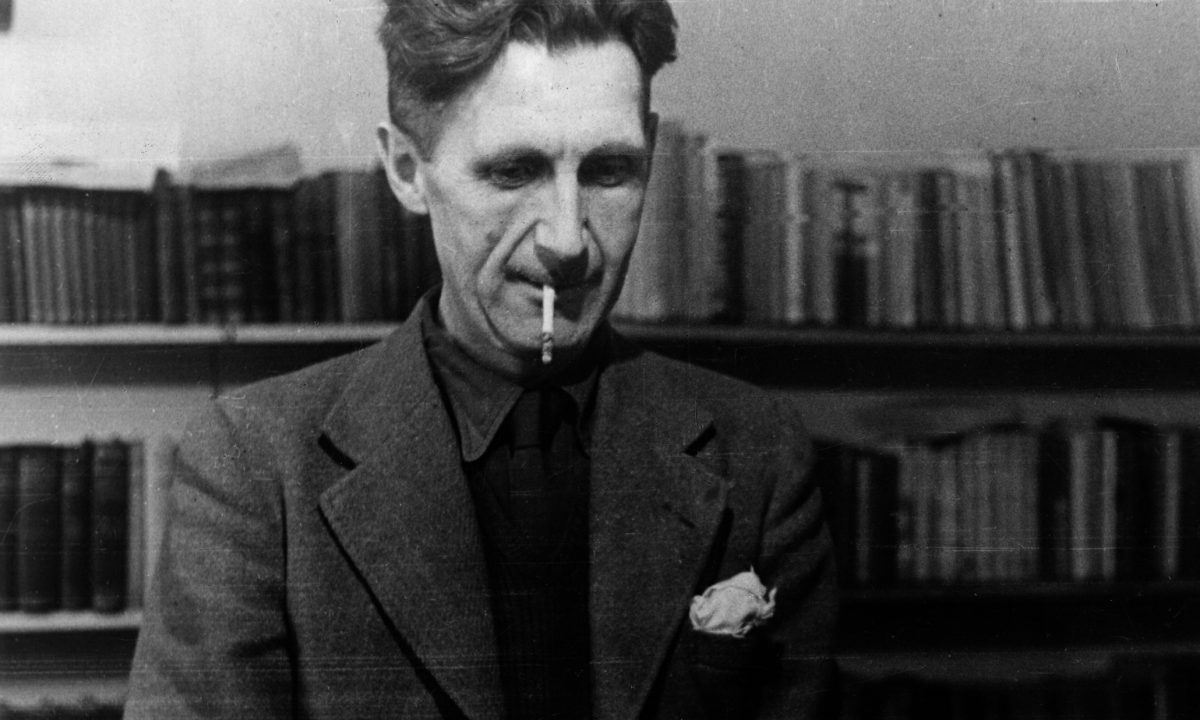

by Umberto Eco

In 1953 Ian Fleming published the first novel in the 007 series, Casino Royale. Being a first work, it is subject to the then current literary influence, and in the fifties, which had abandoned the traditional detective whodunit trail in favour of violent action, it was impossible to ignore the presence of Spillane.

To Spillane, Casino Royale owes, beyond doubt, at least two characteristic elements. First of all the girl Vesper Lynd, who arouses the confident love of Bond, in the end is revealed as an enemy agent. In a novel by Spillane the hero would have killed her, while in Fleming the woman had the grace to commit suicide; but Bond’s reaction when it happens has the Spillane characteristic of transforming love into hatred and tenderness to ferocity: “She’s dead, the bitch” Bond telephones to his London office, and so ends his romance.

In the second place Bond is obsessed by an image: that of a Japanese expert in codes whom he had killed in cold blood on the thirty-sixth floor of the R.C.A. Skyscraper at Rockefeller Centre—with a bullet—from a window of the fortieth floor of the skyscraper opposite. By an analogy that is surely not accidental, Mike Hammer seemed to be consistently haunted by the memory of a small Japanese he killed in the jungle during the war, though with greater emotive participation (while Bond’s homicide, authorised officially by the double-zero, is more ascetic and bureaucratic). The memory of the Japanese was the beginning of the undoubted nervous disorder of Mike Hammer (of his sadistic masochism, of his arguable impotence); the memory of his first homicide could have been the origin of the neurosis of James Bond, except that, within the ambit of Casino Royale, either the character or his author solves the problem by non-therapeutic means: that is by excluding the neurosis from the narrative. This decision was to influence the structure of the following eleven novels by Fleming and presumably forms the basis for their success.

After having helped to dispose of two Bulgarians who had tried to get rid of him, after having suffered torture in the form of a cruel abuse of his testicles, having been present at the elimination of Le Chiffre by the action of a Soviet agent, having received from him a scar on the hand, cold-bloodedly carved while he was conscious, and after having risked the effect on his love life. Bond, enjoying his well-earned convalescence on a hospital bed, confided a chilling doubt to his French colleague, Methis. Have they been fighting for a just cause? Le Chiffre, who had financed Communist spies among the French workers, was he not “serving a wonderful purpose, a really vital purpose, perhaps the best and highest purpose of all”? The difference between good and evil, is it really something neat, recognisable, as the hagiography of counter-espionage would like us to believe? At this point Bond is ripe for the crisis, for the salutary recognition of universal ambiguity, and he sets off along the route traversed by the protagonist of le Carré. But in the very moment when he questions himself about the appearance of the devil and, sympathising with the Enemy, is inclined to recognise him as a “lost brother”, James Bond is treated to a salve from Mathis: “When you get back to London you will find there are other Le Chiffres seeking to destroy you and your friends and your country. M will tell you about them. And now that you have seen a really evil man, you will know how evil they can be and you will go after them to destroy them in order to protect yourself and the people you love. You know what they look like now and what they can do to people. . . . Surround yourself with human beings, my dear James. They are easier to fight for than principles. But don’t let me down and become human yourself. We could lose such a wonderful machine.”

With this lapidary phrase Fleming defines the character of James Bond for the novels to come. From Casino Royale there remained the scar on his cheek, the slightly cruel smile, the taste for good food, together with a number of subsidiary characteristics minutely documented in the course of this first volume: but convinced by Mathis’s words. Bond was to abandon the treacherous life of moral meditation and of psychological anger, with all the neurotic dangers that they entail. Bond ceased to be a subject for psychiatry and remained at the most a physiological object (except for a return to the subject of the psyche in the last, untypical novel in the series, The Man with the Golden Gun), a magnificent machine, as the author and the public, as well as Mathis, had wished. From that moment Bond did not meditate upon truth and upon justice, upon life and death, except in rare moments of boredom, usually in the bar of an airport, but always in the form of a casual daydream, never allowing himself to be infected by doubt (at least in novels—he did indulge in such intimate luxuries in the short stories).

From the psychological point of view a conversion has taken place quite suddenly, on the base of four conventional phrases pronounced by Mathis, but the conversion was not really justified on a psychological level. In the last pages of Casino Royale Fleming, in fact, renounces all psychology as the motive of narrative and decides to transfer characters and situations to the level of an objective and conventional structural strategy. Without knowing it, Fleming makes a choice familiar to many contemporary disciplines: he passes from the psychological method to that of the formula.

In Casino Royale there are already all the elements for the building of a machine that would function basically as a unit along very simple, straight lines, conforming to the strict rules of combination. This machine, which was to function without deviation of fortune in the novels that followed, lies at the basis of the success of the “007 saga”—a success which, singularly, has been due both to the adulation of the masses and to the appreciation of more sophisticated readers. We intend here to examine in detail this narrating machine in order to identify the reasons for its success. It is our plan to devise a descriptive table of the narrative structure in Ian Fleming while seeking to evaluate for each structural element the probable incidence upon the reader’s sensitivity. We shall try, therefore, to distinguish such a narrative structure at five levels:

-

The juxtaposition of the characters and of values.

-

Play situations and the plot as a “game”.

-

A Manichean ideology.

-

Literary techniques.

-

Literature as montage.

Our enquiry covers the range of the following novels listed in order of publication (the date of composition was presumably a year earlier in each case):

Casino Royale, 1953

Live and Let Die, 1954

Moonraker, 1955

Diamonds are Forever, 1956

From Russia with Love, 1957

Dr. No, 1958

Goldfinger, 1959

Thunderball, 1961

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, 1963

You Only Live Twice, 1964

We shall refer also to the stories in For Your Eyes Only (1960), and to The Man with the Golden Gun published in 1965. But we shall not take into consideration The Spy who Loved Me (1962), which seems quite untypical.

1. The Juxtaposition of the Characters and of Values

The novels of Fleming seem to be built on a series of “oppositions” which allow a limited number of permutations and reactions. These dichotomies constitute a constant feature around which minor couples rotate and they form, from novel to novel, variations on them. We have here singled out fourteen couples, four of which are contrasted to four actual characters, while the others form a conflict of values, variously personified by the four basic characters. The fourteen couples are:

(a) Bond—M

(b) Bond—Villain

(c) Villain—Woman

(d) Woman—Bond

(e) Free World—Soviet Union

(f) Great Britain—Countries not Anglo-Saxon

(g) Duty—Sacrifice

(h) Cupidity—Ideals

(i) Love—Death

(j) Chance—Planning

(k) Luxury—Discomfort

(l) Excess—Moderation

(m) Perversion—Innocence

(n) Loyalty—Disloyalty

These pairs do not represent “vague” elements but “simple” ones that are immediate and universal, and if we consider the range of each pair we see that the variants allowed cover a vast field and in fact include all the narrative ideas of Fleming.

In Bond-M there is a dominated-dominant relationship which characterises from the beginning the limits and possibilities of the character of Bond and sets events moving. The interpretation, psychological or psychoanalytical, of Bond’s attitude towards M has been discussed in particular by Kingsley Amis (cf. the last essay in this volume, “James Bond and Criticism”). The fact is that even in terms of pure fictional functions M represents to Bond the one who holds the key to action and to knowledge. Hence his superiority over his employee who depends upon him, and who sets out on his various missions in conditions of inferiority to the omniscience of his chief. Frequently his chief sends Bond into adventures of which he had discounted the upshot from the start. Bond is thus often the victim of a trick, albeit a popular one—and it does not matter that in the event things happen to him beyond the cool calculations of M. The tutelage under which M holds Bond— obliged against his will to visit a doctor, to undergo a nature cure (Thunderball), to change his gun (Dr. No)—makes so much the more insidious and imperious his chiefs authority. We can, therefore, see that M represents certain other virtues, like the religion of Duty, Country and Order (which contrasts with Bond’s own inclination to rely on improvisation). If Bond is the hero and hence possesses exceptional qualities, M represents Moderation, accepted perhaps as a national virtue. In reality Bond is not so exceptional as a hasty reading of the books (or the spectacular interpretation which films give of the books) might make one think. Fleming always affirmed that he had thought of Bond as an absolutely ordinary person, and it is in contrast with M that the real stature of 007 emerges, endowed with physical attribute, with courage and fast reflexes, without possessing any other quality in excess. It is rather a certain moral force, an obstinate fidelity to the job—at the command of M, always present as a warning—that allows him to overcome superhuman ordeals without exercising any superhuman faculty.

The Bond-M relationship indubitably presupposes an affectionate ambivalence, a reciprocal love-hate, and this without need to resort to psychology. At the beginning of The Man with the Golden Gun, emerging from a lengthy amnesia and conditioned by the Soviets, he tries a kind of actual parricide by shooting at M with a cyanide pistol: the gesture loosened a long-standing series of tensions (in the narrative) which were aggravated every time that M and Bond found themselves face to face.

Started by M on the road of Duty (at all costs), Bond enters into conflict with the Villain. The opposition brings into play diverse virtues, some of which are only variants of the basic couples previously paired and listed. Bond indubitably represents Beauty and Virility as opposed to the Villain, who appears often monstrous and sexually impotent. The monstrosity of the Villain is a constant point, but to emphasize it we must here introduce an idea of the method which will also apply in examining the other couples. Among the variants we must consider also the existence of secondary characters whose functions are understood only if they are seen as “variations” of one of the principal personages, some of whose characteristics they “wear”. The vicarious roles function usually for the Woman and for the Villain; also for M—certain collaborators with Bond represent the M figure; for example Mathis in Casino Royale, who preaches Duty in the appropriate M manner (albeit with a cynical and Gallic air). As to the characteristics of the Villain, let us consider them in order. In Casino Royale Le Chiffre is pallid and smooth, with a crop of red hair, an almost feminine mouth, false teeth of expensive quality, small ears with large lobes and hairy hands. He did not smile. In Live and Let Die, Mr. Big, a Haiti Negro, had a head that resembles a football, twice the normal size, and almost spherical; “the skin was grey-black, taut and shining like the face of a week-old corpse in the river. It was hairless, except for some grey-brown fluff above the ears. There were no eyebrows and no eyelashes and the eyes were extraordinarily far apart so that one could not focus on them both, but only on one at a time. . . . They were animal eyes, not human, and they seemed to blaze.” The gums were pale pink.

In Diamonds are Forever the villain appears in three different forms. They are first of all Jack and Seraffino Spang, the first of whom had a humped back and red hair (“Bond did not remember having seen a red-haired hunchback before”), eyes which might have been hired from a taxidermist, big ears with rather exaggerated lobes, dry red lips, and an almost total absence of neck. Seraffino had a face the colour of ivory, black puckered eyebrows, a bush of shaggy hair, jutting, ruthless jaws: if it is added that Seraffino used to pass his days in a Spectreville of the old West dressed in black leather chaps embellished with leather, silver spurs, pistols with ivory butts, a black belt and ammunition—also that he used to drive a train of 1870 vintage furnished with a Victorian carriage in Technicolor—the picture is complete. The third vicarious figure is that of Senor Winter, who travels with a ticket which reads; “My blood group is F\ and who is really a killer in the pay of the Spangs and is a gross and sweating individual with a wart on his hand, a placid visage, and protruding eyes.

In Moonraker, Hugo Drax is six feet tall, with “exceptionally broad” shoulders, has a large and square head, red hair. The right half of his face is shiny and wrinkled from unsuccessful plastic surgery, the right eye different from the left and larger because of a contraction of the skin of the eyelashes (“painfully bloodshot–’), has heavy moustaches, whiskers to the lobes of his ears, and patches of hair on his cheekbones: the moustaches concealed with scant success a prognathous upper jaw and a marked protrusion of his upper teeth. The backs of his hands are covered with reddish hair, and altogether he evokes the idea of a ringmaster at the circus.

In From Russia with Love the villain appears in the shape of three vicarious figures: Red Grant, the professional murderer in the pay of SMERSH, with short, sandy- coloured eyelashes, colourless and opaque blue eyes, a small, cruel mouth, innumerable freckles on his milk- white skin, and deep, wide pores; Colonel Grubozaboyschikov, head of SMERSH, has a narrow and sharp face, round eyes like two polished marbles, weighed down by two flabby pouches, a broad and grim mouth and a shaven skull; finally Rosa Klebb, with the humid pallid lip stained with nicotine, the raucous voice, flat and devoid of emotion, is five feet four, no curves, dumpy arms, short neck, too sturdy ankles, grey hairs gathered in a tight “obscene” bun. She has shiny yellow-brown eyes, thick glasses, a sharp nose white with powder and large nostrils. “The wet trap of a mouth, that went on opening and shutting as if it was operated by wires under the chin” completes the appearance of a sexually neuter person. In From Russia there occurs a variant that is discernible only in a few other novels; there enters also upon the scene a strongly drawn being who has many of the moral qualities of the Villain but uses them in the end for good or at least fights on the side of Bond. In From Russia an example is Darko Kerim, the Turkish agent. Analogous to him is the head of the Japanese secret service in You Only Live Twice, Tiger Tanaka; Draco in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Enrico Colombo in “Risico” (a story in For Your Eyes Only) and—partially—Quarrel in Dr. No. These characteristics are at the same time representative of the Villain and of M and we shall call them “ambiguous representatives”. With these Bond always stands in a kind of competitive alliance, he likes them and hates them at the same time, he uses them, and admires them, he dominates them and is their slave.

In Dr. No, the Villain, besides his great height, is characterised by the lack of hands, which are replaced by two metal pincers. His shaven head has the appearance of a reversed raindrop, his skin is clear, without wrinkles, the cheekbones are as smooth as fine ivory, his eyebrows dark as though painted on, his eyes are without eyelashes and look “like the mouths of two small revolvers”, his nose is thin and ends very close to his mouth, which shows only cruelty and authority.

In Goldfinger the eponymous character is absolutely a textbook monster; that is to say he is characterised by a lack of proportion: “He was short, not more than five feet tall, and on top of the thick body and blunt peasant legs was set almost directly into the shoulders a huge and, it seemed, exactly round head. It was as if he had been put together with bits of other people’s bodies. Nothing seemed to belong.”

His “representative” figure is that of the Korean, Odd- job, with fingers on his hands like spatulas, with fingertips like solid bone, a man who could smash the wooden balustrade of a staircase with a karate blow.

In Thunderball there appears for the first time Ernst Starvo Blofeld. who crops up again in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service and You Only Live Twice, where in the end he dies. As his vicarious incarnations, we have in Thunderball Count Lippe and Emilio Largo; both are handsome and personable, however vulgar and cruel, and their monstrosity is purely mental. In On Her Majesty’s Secret Service there appears Irma Blunt, the soul damned by Blofeld, a distant reincarnation of Rosa Klebb, and a series of villains in outline who perish tragically, killed by an avalanche or by a train. In the third book the primary role is resumed and results in the finish of the monster Blofeld, already described in Thunderball, two eyes that resemble two deep pools, surrounded “like the eyes of Mussolini” by clear whites, of a symmetry which recalls the eyes of a doll, also because of silken black eyelashes of feminine type; two eyes with a child-like gaze, and a mouth like a badly healed wound under a heavy squat nose; altogether an expression of hypocrisy, tyranny and cruelty “on a Shakespearean level”; twenty stone in weight; as we learn in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Blofeld lacks lobes to his ears. His hair is a wiry black crewcut. This curious similarity of appearance among all the Villains in turn suggests a certain unity to the Bond-Villain relationship, especially when it is added that as a rule the wicked are distinguished also by certain racial and “biographical” characteristics.

The Villain is born in an ethnic area that stretches from central Europe to the Slav countries and to the Mediterranean basin: as a rule he is of mixed blood and his origins are complex and obscure; he is asexual or homosexual, or at any rate is not sexually normal: he has exceptional inventive and organisational qualities which help him acquire immense wealth and by means of which he usually works to help Russia: to this end he conceives a plan of fantastic character and dimensions, worked out to the smallest detail, intended to create serious difficulties either for England or the Free World in general. In the figure of the Villain, in fact, there are gathered the negative values which we have distinguished in some pairs of opposites, the Soviet Union and countries which are not Anglo-Saxon (the racial convention blames particularly the Jews, the Germans, the Slavs and the Italians, always depicted as half- breeds), Cupidity elevated to the dignity of paranoia, Planning as technological methodology, satrapic luxury, physical and psychical Excess, physical and moral Perversion, radical Disloyalty.

Le Chiffre, who organises the subversive movement in France, comes from “a mixture of Mediterranean with Prussian or Polish strains, and has Jewish blood revealed by small ears with large lobes”. A gambler not basically disloyal, he still betrays his own bosses, and tries to recover by criminal means money lost in gambling, is a masochist (at least so the Secret Service dossier proclaims), entirely heterosexual, has bought a great chain of brothels, but has lost his patrimony by his exalted manner of living.

Mr. Big is a Negro enjoying with Solitaire an ambiguous relationship of exploitation (he has not yet acquired her favours), helps the Soviet by means of his powerful criminal organisation founded on the voodoo cult, finds and sells in the United States treasure hidden in the seventeenth century, controls various rackets, and is prepared to ruin the American economy by introducing, through the black market, large quantities of rare coins.

Hugo Drax displays indefinite nationality—he is English by adoption—but in fact he is German: he holds control of columbite, a material indispensable to the construction of reactors, and gives to the British Crown the means of building a most powerful rocket; in reality he plans to make the rocket fall, when tested atomically, on London, and to flee then to Russia (equation Communist-Nazi); he frequents clubs of high class, is passionately fond of bridge, but only enjoys cheating; his hysteria does not permit one to suspect any sexual activity worthy of note.

Of the secondary characters in From Russia the chief are from the Soviets, and obviously in working for the Communist cause enjoys comforts and power; Rosa Klebb, sexually neuter, “might enjoy the act physically, but the instrument was of no importance”; as to Red Grant, he is a werewolf and kills for passion; he lives splendidly at the expense of the Soviet government, in a villa with a bathing pool. The science-fiction plot consists in attracting Bond into a complicated trap, using for bait a woman and an instrument for coding and decoding ciphers, and then killing and checkmating the English counter-spy.

Dr. No is a Chinese-German halfbreed, works for Russia, shows no definite sexual tendencies (having in his power Honeychile he plans to have her torn to pieces by the crabs of Crab Key), he lives on a flourishing guano industry and plans to cause guided missiles launched by the Americans to deviate from their course. In the past he has built up his fortune by robbing the criminal organisation of which he had been elected cashier. He lives, on his island, in a palace of fabulous pomp. Goldfinger has a probable Baltic origin but has also Jewish blood; he lives splendidly from commerce and from smuggling gold, by means of which he finances Communist movements in Europe; he plans the theft of gold from Fort Knox (not its radioactivation as the film states), and to overcome the final barrier sets up an atomic attack in the neighbourhood of N.A.T.O.: he tries to poison the water of Fort Knox; he does not have sexual relationships with the girl that he dominates, limiting himself to the acquisition of gold. He cheats at cards, using expensive devices, like binoculars and radio; he cheats to make money, even though fabulously rich and always travelling with a stock of gold in his luggage.

As to Blofeld, he is of a Polish father and a Greek mother; he exploits his position as telegraph clerk to start a flourishing trade in Poland in secret information, becomes chief of the most extensive independent organisation for espionage, blackmail, rapine and extortion. Indeed with Blofeld Russia ceased to be the constant enemy—because of the general international relaxation of tension—and the part of the malevolent organisation is assumed by spectre. spectre has all the characteristics of smersh, including the employment of Slav-Latin-German elements, the use of torture and the elimination of traitors, the sworn enmity to all the powers of the Free World. Of the science-fiction plans of Blofeld, that of Thunderball consists in stealing from N.A.T.O. two atomic bombs and with these blackmailing England and America. That of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service envisages the training in a mountain clinic of girls with suitable allergies to condition them to spread a mortal virus intended to ruin the agriculture and livestock of the United Kingdom. That of You Only Live Twice, the last stage in Blofeld’s career, starts with a murderous mania but shrinks—upon a greatly reduced political scale—to the preparation of a fantastic suicidal garden near the coast of Japan, which attracts legions of heirs of the Kamikaze, bent on poisoning themselves with exotic, refined and lethal plants, thus doing grave and complex harm to the human patrimony of Japanese democracy. Blofeld’s tendency towards satrapic pomp shows itself in the kind of life he leads in the mountain of Piz Gloria, and more particularly on the island of Kyashu, where he lives in medieval tyranny and passes through his hortus deliciarum clad in metal armour. Previously Blofeld had shown himself ambitious of honours (he aspired to be known as the Count of Bienville), as a master of planning, an organising genius, as treacherous as needs be and sexually impotent—he lived in marriage with Irma Blofeld, also asexual and hence repulsive; to quote the words of Tiger Tanaka, Blofeld “is a devil who has taken human form”.

Only the evil characters of Diamonds are Forever have no connections with Russia. In a certain sense the international gangsterism of the Spangs appears to be an earlier version of spectre. For the rest, Jack and Seraffino possess all the characteristics of the canon.

To the typical qualities of the Villain are opposed the Bond characteristics, in particularly Loyalty to the Service, Anglo-Saxon Moderation opposed to the excess of the halfbreeds, the selection of Discomfort and the acceptance of Sacrifice as against the ostentatious luxury of the enemy, the stroke of opportunistic genius (Chance) opposed to the cold Planning which it defeats, the sense of an Ideal opposed to Cupidity (Bond in various cases wins from the Villain in gambling, but as a rule returns the enormous sums won to the Service or to the girl of the moment, as occurred with Jill Master- son; thus even when he has money it is no longer a primary object). For the rest some oppositions function not only in the Bond-Villain relationship, but even internally in the behaviour of Bond himself; thus Bond is as a rule loyal but does not disdain to overcome a cheating enemy by a deceitful trick, and to blackmail him (cf. Moonraker or Goldfinger). Even Excess and Moderation, Chance and Planning are opposed in the acts and decisions of Bond himself. Duty and Sacrifice appear as elements of internal debate each time that Bond knows he must prevent the plan of the Villain at the risk of his life, and in those cases, the patriotic ideal (Great Britain and the Free World) takes the upper hand. He calls also on the racialist need to show the superiority of the Briton. In Bond there are also opposed Luxury (the choice of good food, care in dressing, preference for sumptuous hotels, love of the gambling table, invention of cocktails etc.) and Discomfort (Bond is always ready to abandon the easy life, even when it appears in the guise of a Woman who offers herself, to face a new aspect of Discomfort, the acutest point of which is torture).

We have discussed the Bond-Villain dichotomy at length because in fact it embodies all the characteristics of the opposition between Eros and Thanatos, the beginning of pleasure and the beginning of reality, culminating in the moment of torture (in Casino Royale explicitly theorised as a sort of erotic relationship between the torturer and the tortured).

This opposition is perfected in the relationship between the Villain and the Woman; Vesper is tyrannised and blackmailed by the Soviet, and therefore by Le Chiffre; Solitaire is the slave of Mr. Big; Tiffany Case is dominated by the Spangs; Tatiana is the slave of Rosa Klebb and of the Soviet Government in general; Jill and Tilly Masterson are dominated, in different degrees, by Goldfinger, and Pussy Galore works to his orders; Domino Vitali is subservient to the wishes of Blofeld through the physical relationship with the vicarious figure of Emilio Largo; the English girl guests of Piz Gloria are under the hypnotic control of Blofeld and the virginal surveillance of Irma Blunt; while Honeychile has a purely symbolic relationship with the power of Dr. No, wandering pure and untroubled on the shores of his cursed island, except that at the end Dr. No offers her naked body to the crabs (Honeychile has been dominated by the Villain through the vicarious effort of the brutal Mander who had violated her, and had justly punished Mander by causing a scorpion to kill him, anticipating the revenge of No—which had recourse to crabs); and finally Kissy Suzuki lived on her island in the shade of the cursed castle of Blofeld, suffering a domination that was purely allegorical, shared by the whole population of the place. In an intermediate position is Gala Brand, who is an agent of the Service but who became the secretary of Hugo Drax and established a relationship of submission to him. In most of the cases this relationship culminated in the torture which the woman underwent along with Bond. Here the Love-Death pair function, also in the sense of a more intimate erotic union of the two through their common trial.

Dominated by the Villain, however, Fleming’s woman has already been previously conditioned to domination, life for her having assumed the role of the villain. The general scheme is (1) the girl is beautiful and good; (2) has been made frigid and unhappy by severe trials suffered in adolescence; (3) this has conditioned her to the service of the Villain; (4) through meeting Bond she appreciates human nature in all its richness; (5) Bond possesses her but in the end loses her.

This curriculum is common to Vesper, Solitaire, Tiffany, Tatiana, Honeychile, Domino; rather hinted at for Gala, equally shared by the three representative women of Goldfinger (Jill, Tilly and Pussy—the first two have had a sad past, but only the third has been violated by her uncle: Bond possessed the first and the third, the second is killed by the Villain, the first tortured with gold paint, the second and third are Lesbians and Bond redeems only the third; and so forth); more diffuse and uncertain for the group of girls on Piz Gloria—each had had an unhappy past, but Bond in fact possessed only one of them (similarly he marries Tracy whose past was unhappy because of a series of unions, dominated by her father Draco, and was killed in the end by Blofeld, who realises at this point his domination and ends by Death the relationship of Love which she entertained for Bond). Kissy Suzuki has been made unhappy by a Hollywoodian experience which has made her chary of life and of men.

In every case Bond loses each of these women, either by her own will or that of another (in the case of Gala it is the woman who marries somebody else, although unwillingly)—either at the end of the novel or at the beginning of the following one (as happened with Tiffany Case). Thus, in the moment in which the Woman solves the opposition to the Villain by entering with Bond into a purificating-purified, saving-saved relationship, she returns to the domination of the negative. In this there is a lengthy combat between the couple Perversion-Purity (sometimes external, as in the relationship of Rosa Klebb and Tatiana) which makes her similar to the persecuted virgin of Richardsonian memory. The bearer of purity, notwithstanding and in spite of the mire, exemplary subject for an alternation of embrace-torture, she would appear likely to resolve the contrast between the chosen race and the non-Anglo-Saxon halfbreed, since she often belongs to an ethnically inferior breed; but when the erotic relationship always ends with a form of death, real or symbolic, Bond resumes willy-nilly the purity of Anglo-Saxon celibacy. The race remains uncontaminated.

2. Play Situations and the Plot as a “Game”

The various pairs of opposites (of which we have considered only a few possible variants) seem like the elements of an ars combinatoria with fairly elementary rules. It is clear that in the engagement of the two poles of each couple there are, in the course of the novel, alternative solutions; the reader does not know at which point of the story the Villain defeats Bond or Bond defeats the Villain, and so on. But towards the end of the book the algebra has to follow a prearranged pattern: as in the Chinese game that 007 and Tanaka play at the beginning of You Only Live Twice, hand beats fist, fist beats two fingers, two fingers beat hand. M beats Bond. Bond beats the Villain, the Villain beats Woman, even if at first Bond beats Woman; the Free World beats the Soviet Union, England beats the Impure Countries, Death beats Love, Moderation beats Excess, and so forth.

This interpretation of the plot in terms of a game is not accidental. The books of Fleming are dominated by situations that we call “play situations”. First of all there are several archetypal situations like the Journey and the Meal; the Journey may be by Machine (and here there occurs a rich symbolism of the automobile, typical of our century), by Train (another archetype, this time of obsolescent type), by Aeroplane, or by Ship. But here it is realised that as a rule a meal, a pursuit by machine or a mad race by train, always takes the form of a challenge, a game. Bond decides the choice of foods as though they formed the pieces of a puzzle, prepares for the meal with the same scrupulous attention to method as he prepares for a game of Bridge (see the convergence, in a means-end connection, of the two elements in Moonraker) and he intends the meal as a factor in the game. Similarly, train and machine are the elements of a wager made against an adversary: before the journey is finished one of the two has finished his moves and given checkmate.

At this point it is useless to record the occurrence of the play situations, in the true and proper sense of conventional games of chance, in each book. Bond always gambles and wins, against the Villain or with some vicarious figure. The detail with which these games are described will be the subject of further consideration in the section which we shall dedicate to literary technique; here it must be said that if these games occupy a prominent space it is because they form a reduced and formalised model of the more general play situation that is the novel. The novel, given the rules of combination of opposing couples, is fixed as a sequence of “moves” inspired by the code, and constituted according to a perfectly prearranged scheme.

The invariable scheme is the following:

A. M moves and gives a task to Bond.

B. The Villain moves and appears to Bond (perhaps in alternating forms).

C. Bond moves and gives a first check to the Villain or the Villain gives first check to Bond.

D. Woman moves and shows herself to Bond.

E. Bond consumes Woman: possesses her or begins her seduction.

F. The Villain captures Bond (with or without Woman, or at different moments).

G. The Villain tortures Bond (with or without Woman).

H. Bond conquers the Villain (kills him, or kills his representative or helps at their killing).

I. Bond convalescing enjoys Woman, whom he then loses.

The scheme is invariable in the sense that all the elements are always present in every novel (so that it might be affirmed that the fundamental rules of the game is “Bond moves and mates in eight moves”—but, due to the ambivalence Love-Death, so to speak, “The Villain countermoves and mates in eight moves”). It is not imperative that the moves always be in the same sequence. A minute detailing of the ten novels under consideration would yield several examples of a set scheme which we might call A.B.C.D.E.F.G.H.I (for example Dr. No), but often there are inversions and variations. Sometimes Bond meets the Villain at the beginning of the volume and gives him a first check, and only later receives his instructions from M: this is the case with Goldfinger, which then presents a different scheme B.C.D.E.A.C.D.F.G.D.H.E.H.I. where it is possible to notice repeated moves. There are two encounters and three games played with the Villain, two seductions and three encounters with women, a first flight of the Villain after his defeat and his ensuing death, etc. In From Russia the company of Villains increases, through the presence of the ambiguous Kerim, in conflict with a secondary Villain Krilenku, and the two mortal duels of Bond with Red Grant and with Rosa Klebb, who was arrested only after having grievously wounded Bond, so that the scheme, highly complicated, is B.B.B.B.D.A.(B.B.C). E.F.G.H.G.H.(I). There is a long prologue in Russia with the parade of the Villain figures and the first connection between Tatiana and Rosa Klebb, the sending of Bond to Turkey, a long interlude in which Kerim and Krilenku appear and the latter is defeated; the seduction of Tatiana, the flight by train with the torture suffered by the murdered Kerim, the victory over Red Grant, the second round with Rosa Klebb who, while being defeated, inflicts serious injury upon Bond. In the train and during his convalescence. Bond enjoys love interludes with Tatiana before the final separation.

Even the basic concept of torture undergoes variations, and sometimes consists in a direct injustice, sometimes in a kind of succession or course of horrors that Bond must undergo, either by the explicit will of the Villain (Dr. No) or accidentally to escape from the Villain, but always as a consequence of the moves of the Villain (e.g., a tragic escape in the snow, pursuit, avalanche, hurried flight through the Swiss countryside in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service). . . .

To sum up, the plot of each book by Fleming is, by and large, like this: Bond is sent to a given place to avert a “science-fiction” plan by a monstrous individual of uncertain origin and definitely not English who. making use of his organisational or productive activity, not only earns money but helps the cause of the enemies of the West. In facing this monstrous being Bond meets a woman who is dominated by him and frees her from her past, establishing with her an erotic relationship interrupted by capture, on the part of the Villain, and by torture. But Bond defeats the Villain, who dies horribly, and rests from his great efforts in the arms of the woman, though he is destined to lose her. One might wonder how, within such limits, it is possible for the inventive fiction-writer to function, since he must respond to a wealth of sensations and unforeseeable surprises. In fact, it is typical of the detective story, either of investigation or of action; there is no variation of deeds, but rather the repetition of a habitual scheme in which the reader can recognise something he has already seen and of which he has grown fond. Under the guise of a machine that produces information the detective story, on the contrary, produces redundancy; pretending to rouse the reader, in fact it reconfirms him in a sort of imaginative laziness, and creates escape not by narrating the unknown but the already known. In the pre- Fleming detective story the immutable scheme is formed by the personality of the detective and of his colleagues, by his method of work and by his police, and within this scheme events are unravelled that are unexpected (and most unexpected of all will be the figure of the culprit). But in the novels of Fleming the scheme follows the same chain of events and has the same characters, and it is always known from the beginning who is the culprit, also his characteristics and his plans. The reader’s pleasure consists of finding himself immersed in a game of which he knows the pieces and the rules—and perhaps the outcome—drawing pleasure simply from following the minimal variations by which the victor realises his objective.

We might compare a novel by Fleming to a game of football, in which we know beforehand the place, the number and the personalities of the players, the rules of the game, the fact that everything will take place within the area of the great pitch; except that in a game of football the final information remains unknown till the very end: who will win? It would be more accurate to compare these books to a game of basketball played by the Harlem Globe Trotters against a small local team. We know with absolute confidence that they will win: the pleasure lies in watching the trained virtuosity with which the Globe Trotters defer the final moment, with what ingenious deviations they reconfirm the foregone conclusion, with what trickeries they make rings round their opponents. The novels of Fleming exploit in exemplary measure that element of foregone play which is typical of the escape machine geared for the entertainment of the masses. Perfect in their mechanism, such machines represent the narrative structure which works upon obvious material and does not aspire to describe ideological details. It is true that such structures inevitably indicate ideological positions, but these ideological positions do not derive so much from the structural contents as from the method of constructing the contents into a narrative.

3. A Manichean Ideology

The novels of Fleming have been variously accused of McCarthyism, of Fascism, of the cult of excess and violence, of racialism, and so on. It is difficult, after the analysis we have carried out, to maintain that Fleming is not inclined to consider the British superior to all Oriental or Mediterranean races, or to maintain that Fleming does not profess a heartfelt anti-Communism. Yet, it is significant that he ceased to identify the wicked with Russia as soon as the international situation rendered Russia less menacing according to the general opinion; it is significant that, while he is introducing the coloured gang of Mr. Big, Fleming is profuse in his acknowledgement of the new African races and of their contribution to contemporary civilisation (Negro gangsterism would represent a proof of the cohesion attained in each country by the coloured people); it is significant that the suspect of Jewish blood in comparison with other bad characters should be allowed a note of doubt as to his guilt. (Perhaps to prove by absolving the inferior races that Fleming no longer shares the blind chauvinism of the common man.) Thus suspicion arises that our author does not characterise his creations in such and such a manner as a result of an ideological opinion but purely from reaction to popular demand.

Fleming intends, with the cynicism of the disillusioned, to build an effective narrative apparatus. To do so he decides to rely upon the most secure and universal principles, and puts into play archetypal elements which are precisely those that have proved successful in traditional tales. Let us recall for a moment the pairs of characters that we placed in opposition: M is the King and Bond the Cavalier entrusted with a mission; Bond is the Cavalier and the Villain is the Dragon; the Lady and Villain stand for Beauty and the Beast; Bond restores the Lady to the fullness of spirit and to her senses, he is the Prince who rescues Sleeping Beauty; between the Free World and the Soviet Union, England and the non-Anglo-Saxon countries represent the primitive epic relationship between the Chosen Race and the Lower Race, between Black and White, Good and Bad.

Fleming is a racialist in the sense that any artist is one if, to represent the devil, he depicts him with oblique eyes; in the sense that a nurse is one who, wishing to frighten children with the bogey-man, suggests that he is black.

It is singular that Fleming should be anti-Communist with the same lack of discrimination as he is anti-Nazi and anti-German. It isn’t that in one case he is reactionary and in the other democratic. He is simply Manichean for operative reasons: he sees the world as made up of good and evil forces in conflict.

Fleming seeks elementary oppositions: to personify primitive and universal forces he has recourse to popular opinion. In a time of international tensions there are popular notions like that of “wicked Communism” just as there are of the unpunished Nazi criminal. Fleming uses them both in a sweeping, uncritical manner.

At the most, he tempers his choice with irony, but the irony is completely masked, and reveals itself only by being incredibly exaggerated. In From Russia his Soviet men are so monstrous, so improbably evil that it seems impossible to take them seriously. And yet in his brief preface Fleming insists that all the atrocities that he narrates are absolutely true. He has chosen the path of fable, and fable must be taken as truthful if it is not to become a satirical fairy-tale. The author seems almost to write his books for a two-fold reading public, aimed at those who will take them as gospel truth or at those who see their humour. But their tone is authentic, credible, ingenious, plainly aggressive. A man who chooses to write in this way is neither Fascist nor racialist; he is only a cynic, a deviser of tales for general consumption.

If Fleming is a reactionary at all. it is not because he identifies the figure of “evil” with a Russian or a Jew. He is reactionary because he makes use of stock figures. The user of such figures which personify the Manichean dichotomy sees things in black and white, is always dogmatic and intolerant—in short, reactionary; while he who avoids set figures and recognises nuances, and distinctions, and admits contradictions, is democratic. Fleming is conservative as, basically, the fable, any fable, is conservative: it is the static inherent dogmatic conservatism of fairy-tales and myths, which transmit an elementary wisdom, constructed and communicated by a simple play of light and shade, and they transmit it by indestructible images which do not permit critical distinction. If Fleming is a “Fascist” it is because the ability to pass from mythology to argument, the tendency to govern by making use of myths and fetishes, are typical of Fascism.

In the mythological background the very names of the protagonists participate, by suggesting in an image or in a pun the fixed character of the person from the start, without any possibility of conversion or change. (Impossible to be called Snow White and not to be white as snow, in face and spirit.) The wicked man lives by gambling? He will be called Le Chiffre. He is working for the Reds? He will be called Red and Grant if he works for money, duly granted. A Korean professional killer by unusual means will be Oddjob, one obsessed with gold Auric Goldfinger; without insisting on the symbolism of a wicked man who is called No, perhaps the half-lacerated face of Hugo Drax would be conjured up by the incisive onomatopoeia of his name. Beautiful and transparent, telepathic, Solitaire would evoke the coldness of the diamond; chic and interested in diamonds, Tiffany Case will recall the leading jewellers in New York, and the beauty case of the mannequin. Ingenuity is suggested by the very name of Honeychile, sensual shamelessness by that of Pussy (a slang reference to female anatomy) Galore (another slang term to indicate “well endowed”). A pawn in a dark game, such is Domino; a tender Japanese lover, quintessence of the Orient, such is Kissy Suzuki (would it be accidental that she recalls the name of the most popular exponent of Zen spirituality?). We pass over women of less interest like Mary Goodnight or Miss Trueblood. And if the name Bond has been chosen, as Fleming affirms, almost by chance, to give the character an absolutely common appearance, then it would be by chance, but also by guidance, that this model of style and of success evokes the luxuries of Bond Street or Treasury bonds.

By now it is clear how the novels of Fleming have attained such a wide success; they build up a network of elementary associations, achieving a dynamism that is original and profound. And he pleases the sophisticated readers who here distinguish, with a feeling of aesthetic- pleasure, the purity of the primitive epic impudently and maliciously translated into current terms; and applaud in Fleming the cultured man, whom they recognise as one of themselves, naturally the most clever and broadminded.

Such praise Fleming might merit if he did not develop a second facet much more cunning: the game of style and culture. By virtue of which the sophisticated reader, detecting the fairy-tale mechanism, feels himself a malicious accomplice of the author, only to become his victim; for he is led on to detect stylistic inventions where there is, on the contrary—as will be shown—a clever montage of déjà vu, a dressing-up of the familiar.

4. Literary Techniques

Fleming “writes well”; in the most banal but honest meaning of the term. He has a rhythm, a polish, a certain sensuous feeling for words. That is not to say that Fleming is an artist; and yet he writes with art.

Translation may betray him. The beginning of Goldfinger: “James Bond stava seduto nella sala d’aspetto dell’aeroporto di Miami. Aveva già bevuto due bourbon doppi ed ora rifletteva sulla vita e sulla morte” (James Bond was seated in the departure lounge of Miami Airport. He had already drunk two double bourbons and was now thinking about life and death) is not the same as: “James Bond, with two double bourbons inside him, sat in the final departure lounge of Miami Airport and thought about life and death.”

In the English phrase there is only one sentence, embellished with one of his crisp expressions. There is nothing more to say. Fleming maintains this standard.

He tells stories that are violent and unlikely. But there are ways and ways of doing so. In One Lonely Night Mickey Spillane describes a massacre carried out by Mike Hammer in this way: “They heard my scream and the awful roar of the gun and the slugs stuttering and whining and it was the last they heard. They went down as they tried to run and felt their legs going out from under them. I saw the general’s head jerk and shudder before he slid to the floor, rolling over and over. The guy from the subway tried to stop the bullets with his hand but just didn’t seem able to make it and joined the general on the floor.”

When Fleming has to describe the death of Le Chiffre in Casino Royale, we meet a technique that is undoubtedly more subtle: “There was a sharp ‘phut’, no louder than a bubble of air escaping from a tube of toothpaste. No other noise at all, and suddenly Le Chiffre had grown another eye, a third eye on a level with the other two, right where the thick nose started to jut out below the forehead. It was a small black eye, without eyelashes or eyebrows. For a second the three eyes looked out across the room and then the whole face seemed to slip and go down on one knee. The two outer eyes turned trembling up towards the ceiling.”

There is more shame, more reticence, more respect than in the uneducated outburst of Spillane; but there is also a more baroque feeling for the image, and a total adaptation of the image without emotional comment, and a use of words that designate things with accuracy.

It is not that Fleming renounces explosions of Grand Guignol, he even excels in them and scatters them through his novels: but when he orchestrates the macabre on a wide screen, even here he reveals much more literary venom than Spillane possesses.

Consider the death of Mr. Big in Live and Let Die. Bond and Solitaire, tied by a long rope to the bandit’s ship, have been dragged behind in order to be torn to pieces upon the coral rocks in the bay; but in the end the ship, shrewdly mined by Bond a few hours earlier, blows up, and the two victims, now safe, witness the miserable end of Mr. Big, shipwrecked and devoured by barracuda: “It was a large head and a veil of blood streamed down over the face from a wound in the great bald skull. Bond could see the teeth showing in a rictus of agony and frenzied endeavour. Blood half veiled the eyes that Bond knew would be bulging in their sockets. He could almost hear the great diseased heart thumping under the grey-black skin. The Big Man came on. His shoulders were naked, his clothes stripped off him by the explosion, Bond supposed, but the black silk tie had remained and it showed round the thick neck and streamed behind the head like a Chinaman’s pigtail. A splash of water cleared some blood away from the eyes. They were wide open, staring madly towards Bond. They held no appeal for help, only a fixed glare of physical exertion. Even as Bond looked into them, now only ten yards away, they suddenly shut and the great face contorted in a grimace of pain. ‘Aaarh,’ said the distorted mouth. Both arms stopped flailing the water and the head went under and came up again. A cloud of blood welled up and darkened the sea. Two six-foot thin brown shadows backed out of the cloud and then dashed back into it. The body in the water jerked sideways. Half of the Big Man’s left arm came out of the water. It had no hand, no wrist, no wrist-watch. But the great turnip head, the drawn-back mouth full of white teeth almost splitting it in half, was still alive. The head floated back to the surface. The mouth was closed. The yellow eyes seemed still to look at Bond. Then the shark’s snout came right out of the water and it drove in towards the head, the lower curved jaw open so that light glinted on the teeth. There was a horrible grunting scrunch and a great swirl of water. Then silence.”

For this parade of the terrifying there are indubitably precedents in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: the final carnage, preceded by torture and painful imprisonment (preferably with a virgin), is Gothic, of the purest water. The page quoted here is condensed, Mr. Big suffers even more agonies; and in the same manner Lewis’s Monk was dying for several days with a lacerated corpse beside him on a steep cliff. But the Gothic terrors of Fleming are described with a physical precision, a detailing by images, and for the most part by images of things. The absence of the watch on the wrist bitten off by the shark is not just an example of macabre sarcasm: it is an emphasis on the essential by the inessential, typical of a factual narrative, of a technique with the contemporary stamp.

And here let us introduce a further opposition which affects not so much the structure of the plot as that of Fleming’s style: the distinction between a narrative incorporating wicked and violent acts and a narrative that proceeds by trifling acts seen with disillusioned eyes.

In fact, what is surprising in Fleming is the minute and leisurely concentration with which he pursues for page after page descriptions of articles, landscapes and events apparently inessential to the course of the story; and conversely the feverish brevity with which he covers in a few paragraphs the most unexpected and improbable actions. A typical example is to be found in Goldfinger, with two long pages dedicated to a casual meditation on a Mexican murder, fifteen pages dedicated to a game of golf, twenty-five occupied with a long car trip across France, as against the four or five pages which cover the arrival at Fort Knox of a false hospital train and the coup de théâtre which culminated in the failure of Goldfinger’s plan and the death of Tilly Masterson.

In Thunderball a quarter of the volume is occupied by descriptions of the naturalist cures Bond undergoes in a clinic, though the events that occur there do not justify lingering over the details of diets, the technique of massage and of Turkish baths; but the most disconcerting passage is perhaps that in which Domino Vitali, after having told Bond her life-story in the bar of the Casino, monopolizes five pages to describe, with great detail, the box of Player’s cigarettes. This is something quite different from the thirty pages employed in Moonraker to describe the preparations and the development of the bridge party with Sir Hugo Drax. There at least suspense is set up, in a definitely masterly manner, even for those who do not know the rules of bridge; here, on the contrary, the passage is an interruption and does not seem necessary to characterise the dreaming spirit of Domino by depicting in such an abundance of nuances her tendency to daydream aimlessly.

But “aimless” is the only word. It is “aimless” to introduce diamond-smuggling in South Africa in Diamonds are Forever, which opens with the description of a scorpion, as though seen through a magnifying glass, enlarged to the size of some prehistoric monster, as the protagonist in a story of life and death at animal level, interrupted by the sudden appearance of a human being who crushes the scorpion. Then the action of the book begins, as though what has gone before represents only the titles, cleverly presented, of a film which then proceeds in a different manner.

And even more typical of this technique of the aimless glance is the beginning of From Russia with Love where we have a whole page of virtuosity exercised upon the body, death-like in its immobility, of a man lying by the side of a swimming-pool being explored pore by pore, hair by hair, by a blue and green dragonfly. And while he infuses the scene with the subtle sense of death, the man moves and frightens away the dragonfly.

The man moves because he is alive and is about to be massaged. The fact that, lying upon the ground, he seems dead has no relevance to the purpose of the narrative that follows. Fleming abounds in such passages of high technical skill which makes us see what he is describing, with a relish for the inessential, and which the narrative mechanism of the plot not only does not require but actually rejects. When the story reaches its fundamental action (the basic “moves” enumerated in an earlier section) this technique of the aimless glance is decisively abandoned. The moments of descriptive reflection, particularly attractive because sustained by polished and effective language, seem to sustain the poles of Luxury and Planning, while those of rash action express the moments of Discomfort and of Chance.

Thus the opposition of the two techniques (or the technique of this opposition of styles) is not accidental. If Fleming’s technique were to interrupt the suspense of a vital action, such as frogmen swimming towards a mortal challenge, to linger over descriptions of submarine fauna and coral formations, it would be like the ingenuous technique of Salgari, who is capable of abandoning his heroes when they stumble over a great root of Sequoia during their pursuit in order to describe the origins, properties, and distribution of the Sequoia in the North American continent.

In Fleming the digression, instead of resembling a passage from an encyclopaedia badly rendered, takes on a twofold shape: first of all it is rarely a description of the unusual—such as occurs in Salgari and Verne—but a description of the already known; in the second place it occurs not as encyclopaedic information but as literary suggestion, which calls for much greater skill.

Let us examine these two points, because they reveal the secret of Fleming’s stylistic technique.

Fleming does not describe the Sequoia that the reader has never had a chance to see. He describes a game of canasta, an ordinary motor-car, the control panel of an aeroplane, a railway carriage, the menu of a restaurant, the box of a brand of cigarettes available in any tobacconist. Fleming describes in a few words an assault on Fort Knox because he knows that none of his readers will ever have occasion to rob Fort Knox; and he expands in explaining the gusto with which a steering- wheel or a golf-club can be gripped, because these are acts that each of us has accomplished, may accomplish, or would like to accomplish. Fleming takes time to convey the familiar with photographic accuracy, because it is upon the familiar that he can solicit our capacity for identification. We identify ourselves not with the one who steals an atom bomb but with the one who steers a luxurious motor-launch; not with the one who explodes a rocket but with the one who accomplishes a lengthy ski descent; not with the one who smuggles diamonds but with the one who orders breakfast in a restaurant in Paris. Our credulity is solicited, blandished, directed to the region of possible and desirable things. Here the narration is realistic, the attention to detail intense; for the rest, so far as the unlikely is concerned, a few pages suffice and an implicit wink of the eye. No one has to believe them.

And, again, the pleasure of reading is not given by the incredible and by the unknown but by the obvious and the usual. It is undeniable that Fleming, in exploiting the obvious, uses a verbal strategy of a rare kind, because this strategy which attracts us is incidental, not informative. The language performs the same function as the plots. The greatest pleasure arises not from excitement but from relief. The minute descriptions constitute not encyclopaedic information but literary evocation. Indubitably, if an underwater swimmer swims towards his death and I glimpse above him a sea that is milky and calm and vague shapes of phosphorescent fish which skim by him, his act is inscribed between a cornice of nature and eternity, ambiguous and indifferent, which invokes in me a kind of profound and moral conflict. The impact of apathetic, gorgeous nature expands, and the die is cast. Usually the report when a diver is devoured by a shark says that, and it is enough: if someone embellishes this death with three pages of description of coral, then what would this have to do with Literature?

This reportage, which is not new and is sometimes identified as Midcult or as Kitsch, here finds one of its most efficacious manifestations—we might say the least irritating, through the ease and skill with which its operation is conducted; if it were not that the artifice forces one to praise in Fleming not the shrewd elaboration of the different stories but a feature of stylistic invention.

The play of Midcult in Fleming sometimes shows through (even if none the less efficacious). Bond enters Tiffany’s cabin and shoots the two killers. He kills them, comforts the frightened girl, and gets ready to leave.

“At last, an age of sleep, with her dear body dovetailed against his and his arms around her forever.

“Forever?

“As he walked slowly across the cabin to the bathroom, Bond met the blank eyes of the body on the floor.

“And the eyes of the man whose blood-group had been F spoke to him and said, ‘Mister, nothing is forever. Only death is permanent. Nothing is forever except what you did to me’.”

The brief phrases, in frequent short lines like verse, the indication of the man through the leitmotiv of his blood- group, the biblical figure of speech of the eyes which “talk”; the rapid solemn meditation on the fact—obvious enough—that the dead remain so. . . . The whole outfit of a “universal” fake which MacDonald had already distinguished in the later Hemingway. And, notwithstanding this, Fleming would still be justified in evoking the spectre of the dead man in a manner so synthetically literary if the improvised meditation upon the eternal fulfilled the slightest function in the development of the plot. What will he do now, now that he has been caressed by a shudder for the irreversible, this James Bond? He does absolutely nothing. He steps over the corpse and goes to bed with Tiffany.

5. Literature as Montage

Hence Fleming composes plots that are elementary and violent, played against fabulous opposition, with a technique of novels “for the masses”. Frequently he describes women and scenery, marine depths and motorcars, with a literary technique of reportage, bordering closely upon Kitsch and sometimes failing badly. He blends proper attention to the narrative with an unstable montage, alternating Grand Guignol and nouveau roman, with such broadmindedness in the choice of material as to be numbered, for good or for ill, if not among the inventors at least among the cleverest exploiters of an experimental technique.

It is very difficult, when reading these novels, after their initial diverting impact has passed, to perceive to what extent Fleming simulates literature by pretending to write literature, and to what extent he creates literary fireworks with cynical mocking relish by montage.

Fleming is more literate than he gives one to understand. He begins Chapter 19 of Casino Royale with: “You are about to awake when you dream that you are dreaming.” It is a familiar idea, but it is also a phrase of Novalis. The long meeting of diabolical Russians who are planning the damnation of Bond in the opening chapter of From Russia with Love (and Bond enters the scene unawares, only in the second part) reminds one of a “prologue to inferno” in a memory of Goethe.

We might think that such influences, part of the reading of well-bred gentlemen, may have worked in the mind of the author without emerging into consciousness. Probably Fleming remained bound to an eighteenth- century world, of which his militaristic and nationalistic ideology, his racialist colonialism and his Victorian isolationism are all hereditary traits. His love of travelling, by grand hotels and luxury trains, is completely of the belle époque. The very archetype of the train, of the journey on the Orient Express (where love and death await him), derives from romantic writers, great and small, from Tolstoy by way of Dekobra to Cendrars. His women, as has been said, are Richardsonian Clarissas and correspond to the archetype brought to light by Fiedler (see Amore e morte nella letteratura Americana, Milan, 1964).

But what is more, there is the taste for the exotic, which is not contemporary, even if the islands of sleep are reached by jet. In You Only Live Twice we have a garden of tortures which is very closely related to that of Mirbeau in which the plants are described in a detailed inventory that implies something like the Traite des poisons by Orfila, reached possibly by way of the meditation of Huysmans in La-bas. But You Only Live Twice, in its exotic exaltation (three-quarters of the book is dedicated to an almost mystical initiation to the Orient), in its habit of quoting from ancient poets, recalls also the morbid curiosity with which Judith Gauthier, in 1869, introduced the reader to the discovery of China in Le dragon imperial. And if the comparison appears farfetched—well, then, let us remember that Ko-Li-Tsin, the revolutionary poet, escaped from the prisons of Peking clinging to a kite and Bond escaped from the infamous castle of Blofeld clinging to a balloon (which carried him a long way over the sea where, already unconscious, he was collected by the gentle hands of Kissy Suzuki). It is true that Bond hung on to the balloon remembering having seen Douglas Fairbanks do so, but Fleming is undoubtedly more cultured than his character. It is not a matter of seeking out analogies and of suggesting that there is in the ambiguous and evil atmosphere of Piz Gloria an echo of the magic mountain. Sanatoria are in mountains, and in the mountains it is cold. It is not a question of seeing in Honeychile, who appears to Bond among the foam of the sea, like Anadiomene, the “bird girl” of Joyce. Two bare legs bathed by the waves are the same everywhere. But sometimes the analogies do not concern the simple psychological atmosphere. They are structural analogies. Thus it happens that one of the stories in For Your Eyes Only, “Quantum of Solace”, represents Bond seated upon a chintz sofa of the governor of the Bahamas, listening to him tell, after a lengthy and rambling preamble, in an atmosphere of rarefied discomfort, the long and apparently inconsistent story of an adulterous woman and a vindictive husband; a story without blood and without dramatic action, a story of personal and private actions, after which Bond feels himself strangely upset, and inclined to see his own dangerous activities as infinitely less romantic and intense than certain private and commonplace lives. Now the structure of this tale, the technique of description and the introduction of characters, the disproportion between the preamble and the inconsistency of the story, and between this and the effect it produces, recall strangely the habitual course of many stories by Barbey d’Aurevilly.

And we may also recall that the idea of a human body covered with gold appears in Demetrio Merezkowski (except that in this case the culprit is not Goldfinger but Leonardo da Vinci).

It may be that Fleming had not pursued such varied and sophisticated reading, and in that case one must only assume that, bound by education and psychological make-up to the world of today, he had copied solutions without being aware of them, re-inventing devices that he had smelt in the air. But the most likely theory is that, with the same effective cynicism with which he had constructed his plots according to archetypal oppositions, he had decided that the paths of invention, for the readers of our century, can return to those of the great eighteenth-century serial stories; that as against the homely normality, I do not say of Hercule Poirot, but rather of Sam Spade and Michael Shayne, priests of an urbane and foreseeable violence, he revised the fantasy and the technique that had made Rocambole and Rouletabulle, Fantomas and Fu Manchu famous. Perhaps he has gone further, to the cultured roots of truculent romanticism, and thence to their more morbid affiliations. An anthology of characters and situations treated in his novels would appear like a chapter of The Flesh, Death and the Devil by Praz.

To begin with his evil characters, the red gleams of whose looks and pallid lips recall the archetype of Milton’s Satan, from whom sprang up the romantic generation of darkness:

“In his eyes where sadness lodged and death

Light flashed turbid and Vermillion.

The oblique looks and twisted glares

Were like comets, and like a lamp his lashes

And from the nostrils and pallid lips . . .”

Only that in Fleming an unconscious dissociation is performed, and the characteristics of the fine dark one, fascinating and cruel, sensual and ruthless, are subdivided between the Villain and Bond.

Between these two characters are distributed the traits of the Schedoni of Radcliffe and of the Ambrosio of Lewis, of the Corsair and of the Giaour of Byron; to love and suffer is the fate that pursues Bond like Rene de Chateaubriand, “everything in him turned fatal, even happiness itself. . . But it is the Villain that, like Rene, is “cast into the world like a great disaster, his pernicious influence extended to the beings that surrounded him.”

The Villain, who combined the charm of a great controller of men with great wickedness, is the Vampire, and Blofeld has almost all the characteristics of the Vampire of Merimee (“Who could escape the charm of his glance? . . . His mouth is bleeding and smiles like that of a man drugged and tormented by odious love”).

The philosophy of Blofeld, especially as preached in the poisoned garden of You Only Live Twice, is that of the Divine Marquis in his pure state, perhaps transferred into English by Maturin in Melmoth: “It is quite possible to become lovers of suffering. I have heard of men who have journeyed in countries where every day they are able to attend horrible executions to enjoy the excitement which the sight of the suffering never fails to give. . . And the exposition of the pleasure that Red Grant derives from murder is a minor treatise of sadism. Except that both Red Grant and Blofeld (at least when in the last book he commits evil not for profit but from pure cruelty) are presented as pathological cases. This is natural enough, the times demand compliance, Freud and Kraft-Ebbing have not lived in vain.

It is pointless to linger over the taste for torture except to recall the pages of the Journaux Intimes in which Baudelaire comments on their erotic potentiality; it is pointless perhaps to compare finally the model of Goldfinger, Blofeld, Mr. Big and Dr. No with that of various Supermen of literature. But it cannot be denied that of all such even Bond “wears” several characteristics, and it will be opportune to compare the various physical descriptions of the hero—his ruthless smile, the cruel handsome face, the scar on his cheek, the lock of hair that fell rebelliously over his brow, the taste for display—with this description of a Byronic hero concocted by Paul Feral in Les mystères de Londres:

“He was a man of some thirty years at least in appearance, tall in stature, elegant and aristocratic. . . . As to his face, he offered a notable type of good looks: his brow was high, wide without lines, but crossed from top to bottom by a light scar that was almost imperceptible. … It was not possible to see his eyes; but, under his lowered eyelids, their power could be divined. . . . Girls saw him in dreams with thoughtful eye, brow ravaged, the nose of an eagle, and a smile that was devilish, but divine. … He was a man entirely sensual, capable at the same time of good and of evil; generous by nature, frankly enthusiastic by nature, but selfish on occasion; cold by design, capable of selling the universe for a quarter of gold at his pleasure. … All Europe had admired his oriental magnificence; the universe, after all, knew that he spent four millions every season. . . .”

The parallel is disturbing, but does not prove verbal derivation: the prototype is scattered in hundreds of pages of a literature at first and second hand, and after all a whole vein of British decadence could offer Fleming the glorification of the fallen angel, of the monstrous torturer, of the vice anglais; Wilde, in two passages, accessible to any educated gentleman, was ready to suggest the head of John the Baptist, upon a plate, as a model for the great grey head of Mr. Big floating on the water. As to Solitaire, who withheld herself from him though exciting him, it is Fleming himself who uses, as the title of a chapter, the name of “allumeuse” (tease); her prototype reappears time and again in D’Aurevilly, in the princess d’Este of Péladan, in the Clara of Mirbeau, and in the Madone des Sleepings of Dekobra.

On the other hand, for woman Fleming cannot accept the decadent archetype of the belle dame sans merci, which agrees little with the modern idea of femininity, and he equates her with the model of the persecuted virgin.

However, we are not here concerned with a psychological interpretation of the man Fleming but an analysis of the structure of his text, the relationship between the literary inheritance and the crude chronicle, between eighteenth-century tradition and science fiction, between adventurous excitement and hypnosis which are mingled like the discordant elements of a building that is charming in parts; which often comes to life really by grace of this hypocritical tinkering and often hides its ready-made nature by presenting itself as literary invention. To the extent to which it yields engrossing reading, the work of Fleming represents a successful means of escape, the result of a highly workmanlike narrative; to the extent that he provides to anyone the thrill of poetic emotion, he is yet another exponent of Kitsch; to the extent that he provokes elementary psychological reactions in which ironic detachment is absent, it is only a more subtle but not less mystifying operation of the industry of escape.

And, again, a message does not really end except in a concrete and local reception which qualifies it. When an act of communication provokes a response in public opinion, the definitive verification will take place not within the ambit of the book but in that of the society that reads it.

SOURCE: Eco, Umberto. “The Narrative Structure in Fleming.” In The Bond Affair, edited by Oreste Del Buono and Umberto Eco, translated by R. A. Downie, pp. 35-75. London: Macdonald, 1966.

Twentieth-Century literary criticism, n. 193

1 thought on “UMBERTO ECO: THE NARRATIVE STRUCTURE IN IAN FLEMING”

Pingback: The Failures That Made Ian Fleming - Maltese Puppies For Sale