by Stephen Zito

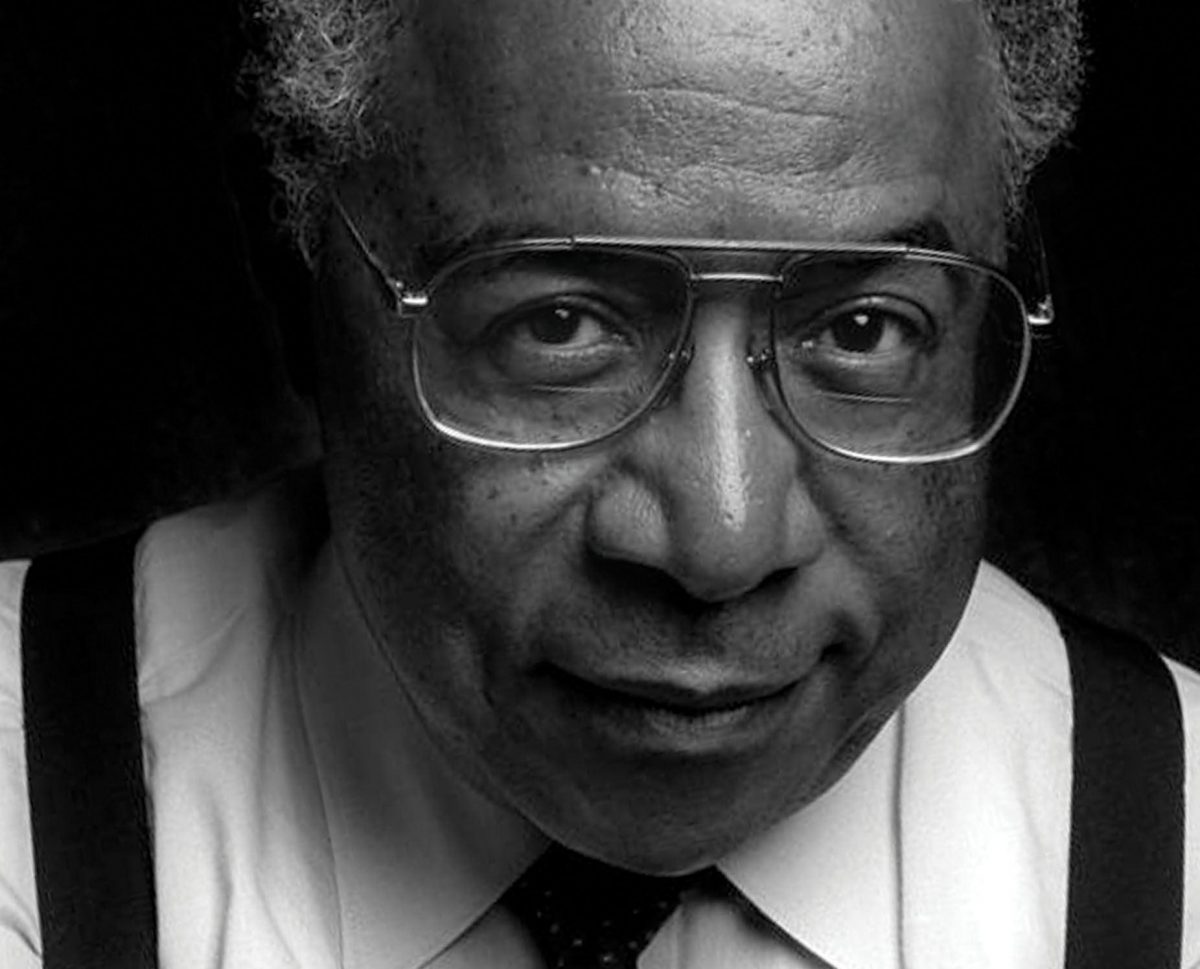

In an African village, an old man had said: “We have been told by the forefathers that there are many of us from this place who are in exile in a place called America.” These words were spoken to Alex Haley, a black American writer, in the village of Juffure in Gambia. The speaker was an ancient griot (or oral historian) who knew by memory, and was to recite that evening, the history of Juffure and of the Kinte family that had lived in that village for centuries. One of the Kinte family, many years before, had been stolen by slavers and taken to the United States.

It was the revelatory evening of his life, Haley remembers, and the culmination of one of the most intriguing and remarkable detective stories of our times. A decade before, Haley had decided to find out everything possible about the origins and history of his family. All he had to go on were his memories of the family stories he had heard as a child in Henning, Tennessee, when he would listen to his grandmother and his aunts talk together on the porch after dinner.

They had told of his great-grandfather, a blacksmith who had been born in slavery and, set free after the Civil War, had traveled by wagon train to Henning: of his grandfather, a hardworking man who had been the first black to own an important business there; and of his father who taught at various agricultural colleges in the South. There were also tales, vaguer and slight, of more distant relatives—slaves who had worked on Virginia and North Carolina plantations in the antebellum South. And there was a treasured family story of the farthest-back person, “The African,” who had been captured by white slavers while he was away from his village cutting wood for a drum; there were even a few African words that had been passed down from generation to generation.

Alex Haley’s difficult search for his roots became an obsession, and he spent twelve years—several of them in debt and plagued by self-doubt—discovering everything he could about the seven American generations of his family. He extensively researched Afro-American life and culture. He read all that he could find on Africa, the history of the slave trade and of slave-ship crossings, and the lives of slaves in America. It was an enlightening period for Haley, a gentle man in his fifties who was then leading a comfortable existence as a free-lance journalist.

“Most people had amorphous ideas about the backgrounds of blacks…including blacks,” Haley observes. “When I first got the concept of going back to Africa to try and find my family, it just rocked me to realize that up until that time—and I was a grown man—my whole image of Africa was gathered very largely from Tarzan movies. When I got my research materials together, I realized that I had much more than the story of a family…I had the story of a people.”

It is an epic saga that Alex Haley has retold in Roots, a 569-page narrative that is being published by Doubleday this month with the largest prepublication printing—200,000—in the company’s history.

Roots begins with the birth of Kunta Kinte in Gambia in 1750. Grown to manhood in freedom and dignity, Kunta is captured by white slavers and brought to America. His foot is cut off during one of several attempts to escape from bondage. He marries a cook on his plantation and has a daughter, Kizzy. She is sold off to another plantation where she is raped by her owner; her mulatto son, Chicken George, becomes one of the premiere cockfighters in the South; and his son, Tom the blacksmith, is freed by the Murray family after Lee surrenders at Appomattox, and he eventually settles in Henning, Tennessee. Other generations are born and die, and the final chapter ends with the recent death of Haley’s father. Roots is the story of an American family that freely mixes documented fact and fiction based on fact. It is a chronicle of America as told by the losers—by what Haley regards as the American serfs: a story of the large miseries and small joys of black existence in hard times. It is also a narrative of success, of freedom rewon, of the achievements of the Haley family in this country, of descendants who became lawyers and architects and writers and businessmen and teachers.

Roots was bought by David L. Wolper and is now the basis for one of the most ambitious and expensive productions ever underwritten by a commercial television network. Wolper Productions is currently completing work on a twelve-hour adaptation of Haley’s novel that will be telecast by the ABC television network with a premiere in January to be followed by weekly installments. “Roots” is the latest in a series of ABC novels for television that began with the six hours of Leon Uris’s “QB VII” and continued last year with the highly successful “Rich Man. Poor Man,” twelve hours of highly polished soap opera mystery from the pen of Irwin Shaw. A long-form version of James Michener’s Hawaii is in the planning stages.

Wolper and ABC are very high on the project and have taken every precaution to safeguard an investment of almost $6 million. Wolper has employed a fair percentage of the top talent in television: writers William Blinn, Ernest Kinoy, James Lee, M. Charles Cohen; directors David Green, Marvin Chomsky, and John Erman; and the cast reads like a broadcasting who’s who. John Amos (“Good Times”) plays Kunta Kinte; Edward Asner (“Mary Tyler Moore Show”) is the Christian ship captain tormented by his involvement with the slave trade; Ralph Waite (“The Waltons”) does a nasty turn as a first mate who uses thumbscrews and black women with equal pleasure; Lorne Green, Vic Morrow, Chuck Connors, John Schuck, and Robert Reed (all TV veterans) are white slave owners or overseers.

Cicely Tyson is Kunta’s mother; Thalmus Rasulala, his father. Lou Gossett is Fiddler, the ebullient slave musician and cynic who is Kunta’s only real friend. Ben Vereen plays Chicken George, the womanizing cockfighter who sports a black derby and a green scarf; Georg Stanford Brown is Tom Murray, the blacksmith; Madge Sinclair, a lovely, dignified Jamaican actress, is Bell, the big house-cook whom Kunta marries; and Leslie Uggams is her daughter.

LeVar Burton, an unknown “discovered” in a sophomore acting class at the University of Southern California drama school, is the young Kunta Kinte. But famous or not, performers wanted very badly to be a part of this production. Sandy Duncan, an established TV star who once had a show of her own, approached Wolper for a part in the series and was even willing to test for a small role as the slaveowner’s daughter who befriends and then betrays a slave girl. It meant that much to her.

The first three hours of “Roots” were shot on location in and around Savannah, Georgia. The last nine hours are being filmed at the Samuel Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood and at Hunter Ranch in Malibu Canyon. It is on stage seven at Goldwyn that director Marvin Chomsky is shooting hours four, five, and six with John Amos, Lou Gossett, Madge Sinclair, and Robert Reed.

The interior of an antebellum mansion occupies most of one end of the stage, and there are other, smaller sets scattered about that represent the interiors of several slave cabins and a kitchen. It is in one of these smaller sets that John Amos is lying on a prop bed. The air is hot under the arcs, and a makeup man sprays Amos’s face and massive naked chest with water to simulate sweat. The Virginia countryside glimpsed outside the window of the jerry-built set is a painted backdrop.

The director Marvin Chomsky gives the command to roll. A group of technicians, black and white, intently watches as Amos does a retake from the previous episode. Kunta Kinte has been captured after an attempt to escape, and cracker slavecatchers have cut off his foot at the arch, crippling him and ending finally his chance to find freedom in the North. Kunta looks away from the bloody cloth covering the stump and agonizingly asks, “What kind of a man do somethin’ like dat to ’nother man?” There is no answer to a question like that.

During the scene, Chomsky crouches at the end of the bed just out of the camera’s range. He whispers directions and, at one point, unexpectedly grabs Amos’s foot and gives it a twist. A flash of pain crosses the actor’s face. (Watching dailies later in the screening room, Chomsky will say, “I almost twisted his damn foot off.”) Amos blows a line, and Chomsky sharply orders him to keep going. Amos repeats the line, and the scene is over. He is emotionally drained— acting does not come easily to him, but he can be good at it. Pleased with the take. Chomsky gives Amos a hug and congratulates him. Amos goes looking for his bathrobe.

Chomsky is a slight man in his late forties, a proponent of living well casually. He arrives on location in a Mercedes and is dressed in old denims and a yellow T-shirt with a picture on it of the “Texas Opry House.” He is a TV veteran. He began as a set designer in the days of live drama on CBS in the fifties and later became a director. Like several others of his TV generation, he alternates between quality TV programs, made-for-television movies (Mrs. Sundance, Little Ladies of the Night), and modest feature films (The Bubble, Evel Knievel, and MacKintosh and T.J., a recent Western starring Roy Rogers on the comeback trail). Chomsky is low-keyed and effective on the set and is surprisingly philosophical and calm in the midst of chaos, settling for the best he can get under the circumstances.

“Everything is a compromise,” he says evenly. “Ido the best I can in the time I have. Television is like a cauldron, a forge. You try for steel and sometimes you end up with gold.” Trained as a set designer, Chomsky sets up all his own camera shots. He is not looking for beauty but for truth. “I try to simplify my camera movements, so my crew doesn’t screw up,” he says. “I set up my shots to preserve the continuity of dramatic relationships between my characters.”

It is performance that counts with Marvin Chomsky. Easy and quiet with his actors, he smiles only for them. When John Amos has trouble with his lines, Chomsky is patient, looking away discreetly when Amos blows a take. He is a very physical director and stands close to Amos during rehearsals and between takes, a hand on Amos’s shoulder. Chomsky is happy with all his actors. “In television you select actors who can give you what you need,” Chomsky explains. “You guide, pull, poke, point out things. But they are not robots, and I am not Svengali. ”

Amos is a big man (240 pounds) who once played professional football for the Kansas City Chiefs and is a veteran of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show.” Amos has just quit the cast of the Norman Lear sitcom “Good Times,” and “Roots” is a test of his serious dramatic talent and ambition. It has also been something of an ordeal for him. He believes that “Roots” is the most meaningful thing he has ever done; meaningful, but not easy. There are subtle shadings to Kunta’s character that elude him, and he is not a quick study. He ruins some takes with small mistakes in line readings, but he always manages at least one good one. Chomsky recognizes that this is a crisis time in Amos’s career and is patient and understanding.

“John worked hard to get where he is,” Chomsky remarks. “He has so much energy, I can’t drain it out of him sometimes. He’s very proud, but very cooperative.” Looking over at the stolid, unpliable Amos, Chomsky deadpans, “Actually, he’s like putty in my hands.”

Talk to the other actors on the show, and they will tell you that “Roots” means something special to them, that it is more than just another job. It is a prestige project, and some of these people will be rightfully nervous at Emmy time. Robert Reed, who plays the kindly doctor and Kunta Kinte’s second master, is steady and reliable. He keeps to himself on the set and tirelessly reads a newspaper between takes. He is sure of his lines and character, and during rehearsals adds bits of actory business for Chomsky’s approval.

Lou Gossett, who is wrapping up his work on the show and is leaving the following week for Bermuda, where he is in the cast of The Deep, is turning in one of the finest performances of a career that includes years of work in television and in films like A Raisin in the Sun, Skin Game, Travels With My Aunt, and The Laughing Policeman. He is very sure of the character of Fiddler and plays him with broad gestures, funky actor’s tricks, and cynical high good humor. Gossett is the perfect foil for the impassive Amos.

“Roots” is particularly meaningful for the black performers. It is the challenge that Amos wanted as an actor, and Gossett remarks that, for one of the few times in his career, he will be billed under his full name, Louis Gossett, Jr. Perhaps Madge Sinclair, who plays Bell, puts it best when she says, “ ‘Roots’ is a huge project on which a lot of good black actors get to work, a good showing for black people in the industry. It also means a lot to me that someone thought enough of a black man’s life to film it.”

The role of Bell is a pleasure for Sinclair. “I’m tickled to death to be working with John Amos and playing his wife,” she says. “I’ve always played all these older, sexless women before, and I have always wanted to play a woman who has feelings of warmth and love. Now at last I get to fall in love with somebody.”

Sinclair is a beautiful woman who speaks with a singer’s clarity and range. She is tall and dignified, a woman sure of herself and letter-perfect in her work. She has a lovely smile full of teeth, full lips, and almost almond-shaped eyes. Jamaican by birth, she was originally trained for the stage. She performed in the Public Theater in New York for several years and appeared in several of Joseph Papp’s workshops and plays—Ti-Jean and His Brothers, The Wedding of Ipheginia, and The Mod Donna. She had a few bit parts in movies that she refuses to mention by name and then received her first significant movie role in Conrack. After that she moved to Los Angeles and found parts in Cornbread, Earl and Me, Leadbelly, and I Will, I Will…for Now. Between films, she has appeared in several unsold TV pilots.

A thoughtful actress, Sinclair, like many performers from the stage, has some difficulty in adjusting to the tight schedules and unique procedures of making films for television. “They have to shoot it out of sequence and it’s hard on me because I am not used to doing things that way. I’m coming in from left field in every scene; I have no concept of my performance; I don’t know what I’m doing most of the time. I just go for it. I make allowances for the variables—the equipment, the other actors. With John Amos, I just hang in there and wait for his good take. I know it will happen. It is a harrowing business. I get myself as prepared as possible and then wait.”

The short schedule of “Roots” does not allow for much rehearsal time. Madge Sinclair comes on the set in the morning with her lines down cold. But she does more than recite words. Her Bell, the housecook, is a woman of dignity and strong character, the very opposite of the traditional Hollywood cook and slave. Sinclair admits that at times playing a mammy has made her uncertain and uneasy. As deeply as she is committed to “Roots,” Sinclair is disturbed that the blacks who appear in the series, like so many of the blacks who have appeared in American movies since the antebellum fantasies of D. W. Griffith, are still slaves.

“I was among those actresses who fought the stereotypes for blacks and women,” Sinclair proudly states. “I wouldn’t do prostitutes, didn’t want to do mammies. But now I am changing Bell from the stereotype of Mammy in Gone With the Wind, because I don’t weigh two hundred pounds and I’m not going to eat myself into a frazzle because that’s the way somebody sees a mammy.” Sinclair then will look you in the eye and say with wry immodesty, “After all. I have two sons, and I’m thin and gorgeous.”

It makes you mad that there aren’t more good roles for women like Madge Sinclair, that she is still walking in the footsteps of Hattie McDaniel. It sometimes makes Sinclair bitter. “Times have not changed all that much,” she insists. “Whatever guise you put it under, people want to see the things that they are familiar with. The fact that Alex Haley’s book approaches slavery from a historical, documentary viewpoint does not excuse the fact that we are dressed in these slave costumes and still saying ‘Yas-suh, Massuh’ and ‘n i g g e r,’ and that little white girl is calling me, ‘Mammy Bell, Mammy Bell.’ ”

Century City is a dark glass and steel phoenix that has risen out of the ashes of what was once the Twentieth Century-Fox back lot. There, in a frigid high rise on the Avenue of the Stars, are located the offices of ABC Television on the West Coast. On a clear day, you can see most of downtown Los Angeles from the forty feet of glass wall along one side of Brandon Stoddard’s deliberately impressive office. Stoddard is a short, immaculately dressed man of enormous energy and enthusiasm. He is the ABC vice president for motion pictures for television and limited series, and he was the guiding force behind “Rich Man, Poor Man,” one of the greatest successes in television history. The Nielsen ratings were massive, and some nights the show had more than a fifty-percent share of the audience.

Stoddard speaks a little nostalgically about “Rich Man”: “It ain’t Shakespeare, but it was a very, very successful novel for TV for ABC.” And he wants the same success for “Roots.” He is not afraid of the critics, for mixed notices did not harm “Rich Man, Poor Man.” He is afraid that viewers may turn the channel for something less demanding.

Stoddard is well aware of the problems that may face “Roots” in terms of public acceptance. He is worried about audience identification and empathy, because the protagonist of “Roots” is not a single man or woman but rather four generations of an American family. And he is also concerned about the reaction of white America to a story that deals candidly, and at length, with black lives and with the savage facts of slavery in America.

“We’ve never been concerned about reaching a black audience,” Stoddard insists. “They’ll watch it no matter what happens. The question is, will we reach a white audience, because there never, never has been a successful black drama series.” Stoddard repeatedly emphasizes in conversation that Roots is a story of universal human appeal. “We did not buy Roots as a project that would deal with black history,” Stoddard states. “It is primarily a story that deals with a family, a very human story. It’s brothers and sisters, greed and lust and fear, and all the things that make real drama. ”

Stoddard knows his audience and that worries him. “We are in a commercial business. When you are plunking down the kind of money we are talking about—which is in excess of $6 million—we don’t want “Roots” mistaken for an educational television venture into the origins of blacks in the U.S.”

ABC is doing everything possible to ensure the success of “Roots.” It recently prepared a half-hour demonstration reel that was presented at a meeting of ABC affiliates (there is concern about some Southern stations pulling out) and is now being shown to journalists visiting the set. The reel is a curious item. There is a brief introduction spoken by Edward Asner, and Asner, along with Ralph Waite, is very prominently featured in the scenes chosen for the reel. LeVar Burton, the much touted USC drama student who is the key character in the episode from which these scenes were culled, is very little in evidence and has almost no dialogue scenes. Judging solely by this assembly. you might infer that “Roots” is really the story of a white slave-ship captain who is tormented by his licentious first mate and by a Christian conscience.

Alex Haley has seen the ABC reel and is philosophical about it. “I understand exactly what they are doing from the network’s point of view,” Haley says evenly. “ABC is putting in all possible big white names, which implies it is not a black story but rather a drama. That’s smart programming. The important thing is to keep every possible person looking at that first show.” Haley, who has a very precise, understated sense of humor that at first goes unnoticed, is a master of the delayed joke. “That reel was put together for presentation to writers and,” he adds wryly, “after all, you wouldn’t want them thinking that this is a black show.”

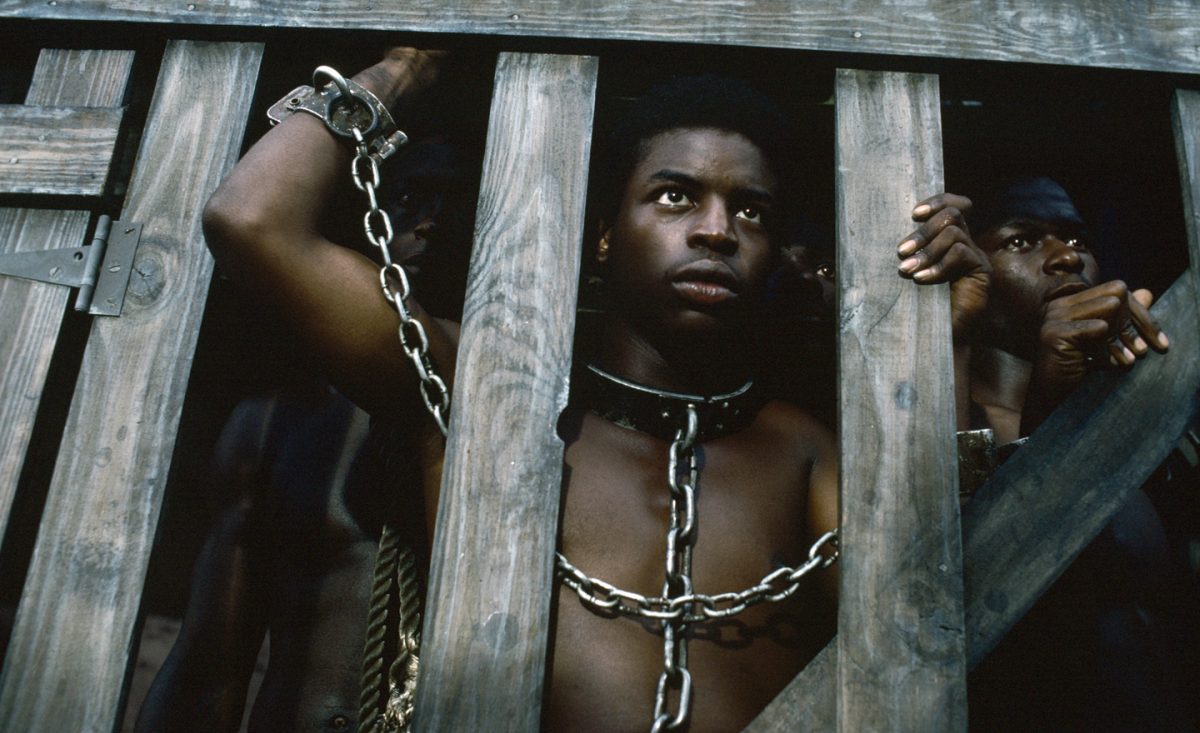

Brandon Stoddard is also concerned about viewer reaction to violence and suffering, for the dramatic continuity of “Roots” is punctuated by scenes of rape, flogging, and mutilation. There is also an extended sequence on board the slave ship Lord Ligoner that is, according to Stoddard, one of the most harrowing moments in the history of TV drama. The claustrophobic hold was re-created in a warehouse in Savannah, Georgia, where a hundred sweating extras were crowded into rough wooden shelves. The degree of realism in these scenes was so strong that it overwhelmed some of those working on the show.

“When we asked the actors to get into the slave-ship hold, it was truly traumatic,” recalls producer Stan Margulies. “You had sixty blacks manacled hand and foot, and we put slop on them and on the floor. It was dark and messy. There is such a thing as ethnic memory, racial memory. After the first day, ninety percent of the extras were reluctant to come back the second day. Burton, who plays the young Kunta, was wiped out. He was emotionally distraught. He went to his motel and didn’t stir because of what it created within.”

Stan Margulies is a Hollywood veteran. He was the producer of Wolper features like Visions of Eight and If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium. More recently, he has worked on several “Movies of the Week” and the TV fact dramas, “I Will Fight No More Forever” and “Collision Course.” Margulies has lived with “Roots” for two years and perhaps better than anyone else knows the logistical, political, and artistic problems of putting on twelve hours of entertaining television that will still be true to Haley’s vision.

Immediately after the novel was bought by Wolper, Margulies went to work with the white writer, William Blinn (Brian’s Song) in order to develop the continuity for the twelve hours of the project. Their work provides an intriguing example of collaborative adaptation. They altered Haley’s book, sometimes significantly, but it was always with the author’s advice and consent. It was, in fact, a condition of the sale of his novel to Wolper that Haley continue through on the project from beginning to end.

Bill Blinn enjoyed working on the show—“It has more merit than a goddamned car chase”—and he found Haley an excellent collaborator. It was, Blinn states, “a mature and adult give-and-take between a writer and the people doing an adaptation of his book. Alex was not coming up with the paranoia of ‘what is Hollywood doing to my book.’ Alex has sometimes stopped us on the basis of inaccuracy—historical or emotional. But he has been open and giving and helpful and willing to trust people. Let’s just say that he has been properly protective of the tone of his work but realistically appreciative of the changes that have been made.”

Margulies and Blinn attempted to be true to the novel and to create a dramatic continuity that would balance the demands of truth and audience appeal. “If I were asking you to watch twelve hours of unrelieved horror—nine hours on board a slave ship and three hours watching people getting whipped on a plantation— that would be a bit much,” says Margulies. “We are also giving you the joyous moments—getting married, having children, passing on the heritage through the children, the eventual reunion of the family, and the moving on as a free people to a new land.”

Margulies has fought to make “Roots” to the highest artistic standard, but there have been times he has been forced to work within the limits of TV drama. He bends the pressure from the ABC Office of Broadcast Standards and Practice and cuts down the number of times the word “n i g g e r” is used in the scripts. ABC has approved some nudity in the African scenes, but Margulies must make sure that no bared female breast is closer to the camera than eighteen feet or larger than a size thirty-two. He accepts the fact that Skidaway Island, off the coast of Georgia near Savannah, must double for Africa. (“How can you do a film about Africa without zebras and alligators?” asks David Green, the director of that segment “We might just slip them into the film by means of a little sleight of hand.”) A movie ranch in Malibu Canyon (where M*A*S*H was shot) must serve as a Southern plantation. A small white house has been constructed that will, with a few changes of potted trees and removable picket fence, be used for several different homes. The cabbages in the garden are plastic.

Margulies is philosophical about working in television: “I wish we had the time,” he says a little wistfully, “to make it as truly fantastic as it can be made. We are dealing with material that’s never been on prime-time television before, and we are dealing with it as authentically and honestly as we know how—not forgetting to make it entertaining. But we must do it on a TV budget and schedule.” Margulies, who speaks slowly, carefully picking his words, sometimes drawing them out unnaturally, is a realist. “As David Wolper frequently reminds me,” he says, “if we were to win every Emmy for ‘Roots,’ we would not get a nickel more for having made it. Half my job is restraining my directors from saying that they need more time for a scene. That’s ultimately the pain in the heart.”

There has been no compromise on hiring the crew for “Roots.” The Wolper organization decided at the beginning of the project to hire as many blacks as possible to work on the series, and it is perhaps the blackest crew ever assembled for a network television series. There are eighteen blacks (forty percent of the crew), and many of them are in key positions of responsibility like Joe Wilcot, the director of photography, and Willie Burton, the lead ma on an all-black sound crew.

Haley remembers vividly a meeting with Wolper in which the subject of black protest and black hiring came up. “Everybody was suddenly looking at me,” he recalls, “My feeling is that Roots is an extremely important story to blacks. I said then that I’d like to see blacks given preference in hiring if a particular black is demonstrably good at what he did. As a result we have a crew that is thrilling to watch in operation. Blacks are doing their jobs superbly and everyone says so.” There are no black writers on the show, but, Haley remarks, “I didn’t care about black writers because I was discussing every script and seeing every draft and revision. I know more about this story than anybody—black, white, or polka dot.”

Writer Bill Blinn recalls a similar discussion. “When I first came onto this project, I said, ‘Well, this is a landmark in black literature. You have to get a black writer.’ And then Alex said, ‘Let me take care of black integrity.’ ” In fact, almost everyone else feels that way about Alex Haley, who is, according to Margulies, “black enough for us all.”

Margulies repeatedly expresses himself satisfied with the crew and regrets not being able to hire more blacks. “Our aim was not to get blacks for the sake of having blacks,” Margulies says, “but it was obviously a project where you wanted a maximum number of blacks. In a couple of cases, we were turned down by blacks to whom we offered jobs because they were making more money doing other things. There was a black art director who said, ‘I’m past doing slave pictures. I’m out doing big expensive white pictures.’ ”

Margulies wanted a black director but it didn’t work out at first. Gordon Parks, Sr., turned down an offer to direct because he was not accustomed to the murderously short TV schedules (twenty-one days to prepare, shoot, and rough-cut an hour segment), and Michael Schulz, the director of Cooley High and Car Wash, was too busy with feature film projects to direct even an hour of “Roots.” A black director, Gilbert Moses (Willie Dynamite), was eventually signed, however.

Relations on the “Roots” sets have been mostly harmonious. Only once, when David Green was shooting on location in Georgia, was there open conflict between blacks on the crew and a white director. Green is an articulate, sometimes abrasive, slightly eccentric English director who is an alumnus of “Rich Man, Poor Man. ”

“At first I felt very self-conscious about being white,” Green recalls. “I realized that this is a black subject and that in another five years it will probably be a black director doing it. But right at this moment it is not considered there are enough black directors with the experience to direct within our tight schedule.” According to the actor Thalmus Rasulala, Green had a remarkable rapport with his actors, but not always with his crew. “We did have on the crew one or two black militants,” Green says. “Those are people who see every manifestation of life in political terms. They questioned one or two things I was doing and imputed white motives to it. I really lammed into them: ‘Just get all that black and white shit off your back,’ I said. ‘I’ve come through it, so let’s get together and get past it. It’s just crap. It just hangs on you and slows you down.’ In the end they did, and it was just fine

People on the set at Goldwyn speak openly and proudly of the rapport between the black and white members of the crew. It seems that times have changed a little—blacks are slowly being accepted by the unions and are finding work. “Blacks are entering a new phase,” Madge Sinclair states. “This is the second part of the revolution that a lot of people are overlooking. The fires and the arrogance and the violence were warnings. But once you’ve burned, you’ve got to build. This crew was not hired just because they were black but because they were good. They were busy studying at the time the others were burning. And now they are equipped. The doors are open, and we are ready to come in.”

Anyone who has been on the set of “Roots” for more than a few hours has met Alex Haley. It is his custom to come by almost every day and speak with the actors and the crew, unobtrusively watching the saga of his family being filmed. It is, Haley admits, a strange feeling—“For years I sat in a room and all I did was type…type…and now all this. I just can’t get used to it.”

It is clear that he is enjoying to the fullest the celebrity and the money that the novel and the TV series are bringing hi.s way. No longer in hock to the credit card companies, he has bought a house in Los Angeles and is spending his days keeping an eye on the progress of the series and talking with journalists. He is a happy man, and you can’t help thinking that it couldn’t happen to a nicer guy. He did, after all, give up twelve years of his life to this project, enduring both the wrath of his creditors and the jokes of his friends about “this endless book.” It was, in the end, all a matter of faith.

Alex Haley was born in Ithaca, New York, in 1922. He spent the first years of his life in Henning, Tennessee, and they were happy years. “I loved boyhood,” Haley says. “One of my great regrets is I ever got grown, ’cause I had such a great life as a boy. I had a good family, loving parents. I just had a ball.” Haley always speaks of his family with great feeling and has plans to write a book called “Henning, Tennessee.”

Haley’s family left Henning in 1929, and Haley grew up elsewhere. He dropped out of college to enlist in the Coast Guard during the Second World War. After twenty years of service, first as a cook and later as a journalist, Haley left the service to continue his career as a free-lance writer, begun while in the Coast Guard. He published a number of sea stories in adventure magazines; he also wrote for Harper’s, The Atlantic, and the New York Times Magazine. And in 1962, his long conversation with jazz trumpeter Miles Davis became the first Playboy interview. Haley continued to write interviews for that magazine over the next four years and spent more than a year taping a series of conversations with the black religious leader, Malcolm X, that became The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

In 1964, Haley went to London to tape an interview with Julie Christie. The interview never took place, and Haley decided to see the sights; he went to the British Museum and chanced upon the Rosetta stone. Fascinated, he bought a book about the methods that British archeologists had used to learn the secrets of the ancient hieroglyphics. The stone was symbolic for Haley, and he began to wonder if he could trace his own African heritage.

He began by checking census records at the National Archives and, with the help of linguists who could identify the few African words—including a family name—still remembered by the Haley family, managed to locate the African tribe in Gambia from which his ancestor had been kidnapped. Haley traveled to the village of Juffure and found a griot who knew the geneologies of that village going back centuries. That evening in Africa, Haley had come full circle. The griot recited for hours until he came to the fate of the oldest son of Omoro Kinte—“About that time the king’s soldiers came, the eldest of his four sons, Kunta, went away from the village to chop wood…and he was never seen again.” Alex Haley had come home.

For a man who loves to talk, Haley is a good listener and is more than likely to flatter the journalists who come to interview him, telling them, “Oh, I just love writers.” But then, he does love writers because he is one himself and has the highest regard for the craft and discipline and profession of writing.

Haley is a wonderful teller of tales. There are few stories as gripping as his rendition of the search for roots. He tells fragments of it during his interviews, and has, for a number of years, made a portion of his living on the college lecture circuit telling the full, all-stops-out, edge-of-the-chair version. He estimates that he has given the lecture a thousand times. Bill Blinn. who accompanied Haley on a lecture tour to a dozen predominantly black colleges in the deep South, speaks of the fervent response to Haley’s chronicle and compares it to a religious experience.

“Haley tailors it to the audience,” Blinn recalls. “White audiences get the same story, but they get more of his gentleness as a human being along with it. I don’t think that’s conscious manipulation but to let them know he’s not out to threaten anyone or put them through an artificial guilt trip. He’s worked his way past all that and is very impatient with it.” Blinn remembers that one of Haley’s problems on the tour was that he couldn’t keep up with the black students’ variety of handshakes —“He’d offer has hand, and instead they’d slap his palm and hit his hip.”

Before the filming of each of the major segments of the TV series, Haley has told this story of his search to the new cast and crew—the few African words he learned from his grandmother; the twelve-year search; the remarkable providence that led him to a small village in Gambia. To hear Haley talk is to become a true believer. “The actors feel in awe of the book,” Blinn says, “and having Alex say to them that he likes the scripts gives them the freedom to change. All Alex would have to do is walk on the set one day and say, ‘It’s not what I had in mind but I guess it will do,’ and you’d be there till midnight.”

Haley enjoys being on the set during production and believes that it has its benefits for him as well as for the show. He is also intrigued by the subtle changes that have been wrought in his characters. “My Fiddler in the book is a cunning character. Lou Gossett has broadened and deepened the character, and I almost prefer Lou’s Fiddler. And my Bell is an older, more solid character, an incipient mammy. I find myself falling in love with the actors’ characters. There they are. They become real because they are there.” And the actors love him. Leaving the set one day he remarked to his companion. “Hey, let’s go around the long way so I can get hugs from two or three pretty girls.” He wasn’t joking.

The night John Amos heard Haley tell the search story the actor was profoundly moved. He embraced Haley afterward and told him that it was a privilege to be acting in the series. John Amos has not lost that sense of dedication, but, as Haley knows, it has been difficult for him. “John had been working on ‘Good Times,’ and I gather from the other actors that it was not as demanding. I have the feeling that John found himself in something that he hadn’t anticipated— the wrenching necessity to go out there and act. Besides, anybody caught between Lou Gossett and Madge Sinclair has got a problem. My friend, the actress Denise Nicholas, just chuckles and says, ‘Lou and Madge will put a hurting on you.’ John has been in a test of major proportions. He has to wrench himself out of just saying lines and act.”

Haley wants to keep close to the action. He genuinely seems to like television work and has moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles in order to be near it. Haley is already talking to Wolper about his participation in a TV documentary based on his next book, which is to be called, not surprisingly, “The Search for Roots.” Haley would also like to produce a series for television. He has already spoken to Brandon Stoddard about the development of a series for ABC that would be based on the life of a family. This may seem a little strange for a man who does not own a TV set and watches, by his own estimate, only a few hours a year.

Haley finds television distracting, and he is very intolerant of anything that distracts him from his work. His only regret about his coming celebrity is that the interviews and the travel will keep him from his work. He is a dedicated researcher and a prodigious writer. Much of his conversation is filled with anecdotes culled during the years of his research. As a former sailor. Haley is fond of sea lore, and some of his slave-ship stories are remarkably chilling.

“There was one kind of disease that the crew lived in dread of,” he will tell you. “The people who were feeding the slaves would notice that one of the slaves was seemingly unable to see, and the slave would be snatched up and tossed overboard, still alive. But once the disease was noticed, it was too late. It started in the hold and then it would spread to the feeders—and they would go overboard, but it was too late. There were cases where slave ships were discovered foundering in the ocean and every soul on board was blind.”

There were times when Haley’s research was harrowing and difficult for him. When he reached the part of his story where the African is chained in the black hold, Haley found that he was unable to imagine what it really must have been like and there was nothing in books that would tell him what he needed to know. “I had this haunting feeling then that I wasn’t fit to write that section. Just researching in documents wasn’t enough qualification.” Haley went to Africa and booked passage to the United States on a freighter, The African Star. It was then that Haley’s research began for real.

“Every evening after dinner,” Haley recalls, “I went down into the deep, dark, cavernous hold. It was uncomfortably cold. I had located a rough-hewn timber and, after I took my clothes off to my underwear, I lay on that dunnage and imagined how it would be for Kunta—what he feels, what does it sound like, what is he thinking.”

It was a method of research that was not without its hazards, and the psychological toll on Haley was high. Midway through the voyage, Haley did not want to return to the hold. “I felt like I was about to go crazy,” Haley said. “I walked out onto the stern and I watched the sunset… I felt terrible. And I looked down at the wake and a quiet thought came into my head—slip under the rail, and all the mess would be over. I wouldn’t owe on no more credit cards. No more publishers bothering me. It was the closest to death I have ever come. It was at this point that I began to hear voices—my grandmother, Chicken George, Kunta. They were all saying, No! No! You must go on and write the book.”

The experience gave Haley the courage to complete his work. “That night was my catharsis. That was the night I felt I was qualified to write, that I deserved to be writing this chronicle. From that time forward, I never doubted that I was fit. I had strength in the telling.”

Alex Haley has a sense of his own destiny. “I feel that I have been chosen,” he says. “The American blacks have traditionally been portrayed as the least among the peoples of the earth. Somehow, when from among us comes this thrust into the past, this dignity and pride and heritage and grasp of self, then it is gripping to everyone else.

The twelfth hour of “Roots” that will be aired next year will end with Alex Haley on camera. “I should imagine that it will be a very dramatic moment when a baby is talked of and I come on camera and I say that I was that baby and I heard this story from my grandmother and she drummed it into me and I knew it as indelibly as I knew the biblical parables and then some thirty years later I got curious and went into the National Archives and found documents and that began twelve years of research, half a million miles, three continents….”

Stephen Zito is a contributing editor of American Film.

American Film, October 1976, pp. 8–17