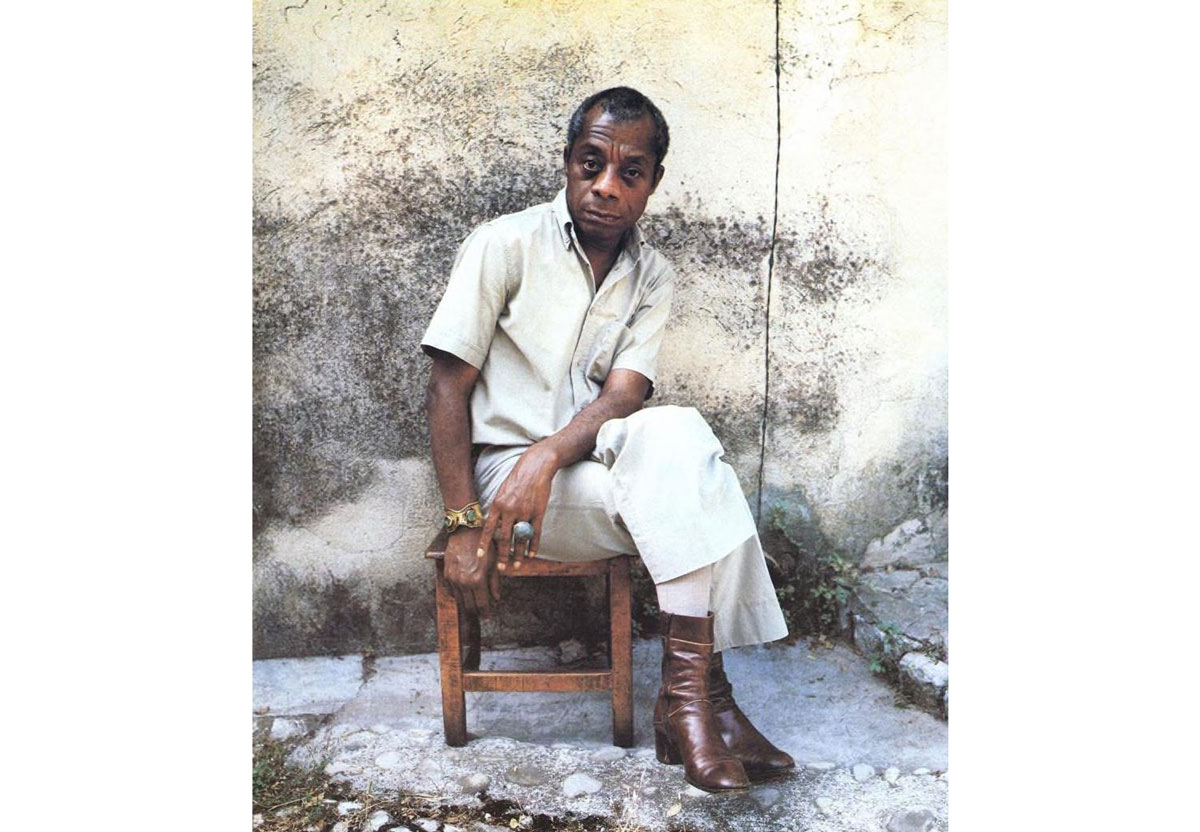

The most provocative black author of our time examines the education of our children, the actions of their elders, and the prospects for our future

by James Baldwin

I hit the streets when I was seven. It was the middle of the Depression and I learned how to sing out of hard experience. To be black was to confront, and to be forced to alter, a condition forged in history. To be white was to be forced to digest a delusion called white supremacy. Indeed, without confronting the history that has either given white people an identity or divested them of it, it is hardly possible for anyone who thinks of himself as white to know what a black person is talking about at all. Or to know what education is.

Not one of us—black or white—knows how to walk when we get here. Not one of us knows how to open a window, unlock a door. Not one of us can master a staircase. We are absolutely ignorant of the almost certain results of falling out of a five-story window. None of us comes here knowing enough not to play with fire. Nor can one of us drive a tank, fly a jet, hurl a bomb, or plant a tree.

We must be taught all that. We have to learn all that. The irreducible price of learning is realizing that you do not know. One may go further and point out—as any scientist, or artist, will tell you—that the more you learn, the less you know; but that means that you have begun to accept, and are even able to rejoice in, the relentless conundrum of your life.

What happens, black poet Langston Hughes asks, to a dream deferred? What happens, one may now ask, when a reality finds itself on a collision course with a fantasy? For the white people of this country have become, for the most part, sleepwalkers, and their somnambulation is reflected in the caliber of U.S. politics and politicians. And it helps explain why the blacks, who walked all those dusty miles and endured all that slaughter to get the vote, are now not voting.

Education occurs in a context and has a very definite purpose. The context is mainly unspoken, and the purpose very often unspeakable. But education can never be aimless, and it cannot occur in a vacuum.

I went to school in Harlem, quite a long time ago, during a time of great public and private strain and misery. Yet I was somewhat luckier than the Harlem children are today. I was going to school in the Thirties, after the stock market crash. My family lived on Park Avenue, just above the uptown railroad tracks. The poverty of my childhood differed from poverty today in that the TV set was not sitting in front of our faces, forcing us to make unbearable comparisons between the room we were sitting in and the rooms we were watching; neither were we endlessly being told what to wear and drink and buy. We knew that we were poor, but then, everybody around us was poor.

The stock market crash had very little impact on our house. We had made no investments, and we wouldn’t have known a stockbroker if one had patted us on the head. The market was part of the folly that always seemed to be overtaking white people, and it was always leading them to the same end. They wept briny tears, they put pistols to their heads or jumped out of windows. That’s just like white folks, was my father’s contemptuous judgment, and we took our cue from him and felt no pity whatever. You reap what you sow, Daddy said, grimly, carrying himself and his lunch box off to the factory, while we carried our lunch boxes off to school and, soon, into the streets, where my brother and I shined shoes and sold shopping bags. Mama went downtown or to the Bronx to clean white ladies’ apartments.

Yet there is a moment from that time that I remember today and will probably always remember—a photograph from the center section of the Daily News. We were starving, people all over the country were starving. Yet here were several photographs of farmers, somewhere in America, slaughtering hogs and pouring milk onto the ground in order to force prices up (or keep them up), in order to protect their profits. I was much too young to know what to make of this beyond the obvious. People were being forced to starve, and being driven to death, for the sake of money. One might say that my recollection of this photograph marks a crucial moment in my education; but one must also say that my education must have begun long before that moment, and dictated my reaction to the photograph. My education began, as does everyone’s, with the people who towered over me, who were responsible for me, who were forming me. They were the people who loved me, in their fashion—whom I loved, in mine. These were people whom I had no choice but to imitate and, in time, to outwit. One realizes later that there is no one to outwit but oneself.

When I say that I was luckier than the children are today, I am deliberately making a very dangerous statement, a statement that I am willing, even anxious, to be called on. A black boy born in New York’s Harlem in 1924 was born of southerners who had but lately been driven from the land, and therefore was born into a southern community. And this was incontestably a community in which every parent was responsible for every child. Any grown-up, seeing me doing something he thought was wrong, could (and did) beat my behind and then carry me home to my Mama and Daddy and tell them why he beat my behind. Mama and Daddy would thank him and then beat my behind again.

I learned respect for my elders. And I mean respect. I do not mean fear. In spite of his howling, a child can tell when the hand that strikes him means to help him or to harm him. A child can tell when he is loved. One sees this sense of confidence emerge, slowly, in the conduct of the child—the first fruits of his education.

Every human being born begins to be civilized the moment he or she is born. Since we all arrive here absolutely helpless, with no way of getting a decent meal or of moving from one place to another without human help (and human help exacts a human price), there is no way around that. But this is civilization with a small c. Civilization with a large C is something else again. So is education with a small e different from Education with a large E. In the lowercase, education refers to the relations that actually obtain among human beings. In the uppercase, it refers to power. Or, to put it another way, my father, mother, brothers, sisters, lovers, friends, sons, daughters civilize me in quite another way than the state intends. And the education I can receive from an afternoon with Picasso, or from taking one of my nieces or nephews to the movies, is not at all what the state has in mind when it speaks of Education.

For I still remember, lucky though I was, that reality altered when I started school. My mother asked me about one of my teachers: was she white or colored? My answer, which was based entirely on a child’s observation, was that my teacher was “a little bit colored and a little bit white.” My mother laughed. So did the teacher. I have no idea how she might react today. In fact, my answer had been far more brutally accurate than I could have had any way of knowing. But I wasn’t penalized or humiliated for my unwitting apprehension of the Faulknerian torment.

Harlem was not an all-black community during the time I was growing up. It was only during the Second World War that Harlem began to become entirely black. This transformation had something to do, in part, with the relations between black and white soldiers called together under one banner. These relations were so strained and volatile that, however equal the soldiers might be deemed, it was thought best to keep them separate when off the base. And Harlem, officially or not, was effectively off limits for white soldiers.

Harlem’s transformation relates to the military in another way. The Second World War ended the Depression by throwing America into a war economy. We are in a war economy still, and we are only slightly embarrassed by the difficulty of officially declaring a Third World War. But where there’s a will, I hate to suggest, there’s often a way.

When I was growing up there were Finns, Jews, Poles, West Indians, and various other exotics scattered all over Harlem. We could all be found eating as much as we could hold in Father Divine’s restaurants for fifteen cents. I fought every campaign of the Italian-Ethiopian War with the oldest son of the Italian fruit and vegetable vendor who lived next door to us. I lost. Inevitably. He knew who had the tanks.

The new prosperity caused many people to pack their bags and go. Some blacks got as far as Queens. Jamaica, or the Bronx. One might say that a certain rupture began during this time. We began to lose each other. The whites who left moved directly into the American mainstream, as we like to say, without the complexity of the smallest regret and without a backward look. The blacks moved into limbo. The doors opened for white people and (especially) for their children. The schools, the unions, industry, and the arts were not opened for blacks. Not then, and not- now.

This meant—means—that the black family had moved onto yet another sector of a vast and endless battlefield. The people I am speaking of came mainly from the South. They had been driven north by the sheer impossibility of remaining in the South. They came with nothing. And the good Lord knows it was a hard journey. Their children had never seen the South; their challenges came from the hard pavements of a hostile city, and their parents had no arms with which to protect them from its devastation.

When I went to work as a civilian for the Army in 1942, I earned about three times as much in a week as my father ever had. This was not without its effect on my father. His authority was being eroded, he was being cheated of the reality of his role. And I, of course, had absolutely no way of understanding the ferocious complexity of his reaction. I did not understand the depth and power and reality of his pain.

The blacks who moved out of Harlem were not received with open arms by their countrymen. They were mocked and despised. and their children were in greater danger than ever. No friendly neighbor was likely to correct the child. The child would either rise up into a seeming responsibility and respectability, one step ahead of paranoia, or drop down to the needle and the prison. And since there is not a single institution in this country that is not a racist institution—beginning with the churches, and by no means ignoring the unions—blacks were unable to seize the tools with which they could forge a genuine autonomy.

The new prosperity also brought in the blight of housing projects to keep the n*gger in his place. Whites, thinking “If you can’t beat them, stone them,” dumped drugs into the ghetto, and what had once been a community began to fragment. The space between people grew wider. The question of identity became a paralyzing one. Being “accepted” could cause even greater anguish, and was a more deadly danger, than being spat on as a n*gger.

I was luckier in school than the children are today. My situation, however grim, was relatively coherent. I was not yet lost. Though most of my teachers were white, many were black. And some of the white teachers were very definitely on the Left. They opposed Franco’s Spain, and Mussolini’s Italy, and Hitler’s Third Reich. For these extreme opinions, several were placed on blacklists and drummed out of the academic community—to the everlasting shame of that community.

The black teachers, paradoxically, were another matter. They were laconic about politics but single-minded about the future of black students. Many of them were survivors of the Harlem Renaissance and wanted us black students to know that we could do, become, anything. We were not, in any way whatever, to be limited by the Republic’s estimation of black people. They had refused to be defined that way, and they had, after all, paid some dues.

I did not, then, obviously, really know who some of these people were. Gertrude E. Ayers, for example, my principal at RS. 24, was the first black principal in the history of New York City schools. I did not know, then, what this meant. Dr. Kenneth Clark informed me in the early Sixties that Ayers was the only one until 1963. And there was the never-to-be-forgotten Mr. Porter, my black math teacher, who soon gave up any attempt to teach me math. I had been born, apparently, with some kind of deformity that resulted in a total inability to count. From arithmetic to geometry, I never passed a single test. Porter took his failure very well and compensated for it by helping me run the school magazine. He assigned me a story about Harlem for this magazine, a story that he insisted demanded serious research. Porter took me downtown to the main branch of the public library at Forty- second Street and waited for me while I began my research. He was very proud of the story I eventually turned in. But I was so terrified that afternoon that I vomited all over his shoes in the subway.

The teachers I am talking about accepted my limits. I could begin to accept them without shame. I could trust them when they suggested the possibilities open to me. I understood why they changed the list of colleges they had hoped to send me to, since I was clearly never going to become either an athlete or a businessman.

I was an exceedingly shy, withdrawn, and uneasy student. Yet my teachers somehow made me believe that I could learn. And when I could scarcely see for myself any future at all. my teachers told me that the future was mine. The question of color was but another detail, somewhere between being six feet tall and being sue feet under. In the long meantime, everything was up to me.

Every child’s sense of himself is terrifyingly fragile. He is really at the mercy of his elders, and when he finds himself totally at the mercy of his peers, who know as little about themselves as he, it is because his peers’ elders have abandoned them. I am talking, then, about morale, that sense of self with which the child must be invested. No child can do it alone.

But children, I submit, cannot be fooled. They can only be betrayed by adults, not fooled—for adults, unlike children, are fooled very easily, and only because they wish to be. Children—innocence being both real and monstrous—intimidate, harass, blackmail, terrify, and sometimes even kill one another. But no child can fool another child the way one adult can fool another. It would be impossible, for example, for children to bring off the spectacle—the scandal—of the Republican or Democratic conventions. They do not have enough to hide—or, if you like, to flaunt.

I remember being totally unable to recite the Pledge of Allegiance until I was seven years old. Why? At seven years old I was certainly not a card-carrying Communist, and no one had told me not to recite “with liberty and justice for all.” In fact, my father thought that I should recite it for safety’s sake. But I knew that he believed it no more than I, and that his recital of the pledge had done nothing to contribute to his safety, to say nothing of the tormented safety of his children.

How did I know that? How does any child know that? I knew it from watching my father’s face, my father’s hours, days, and nights. I knew it from scrubbing the floors of the tenements in which we lived, knew it from the eviction notices, knew it from the bitter winters when the landlords gave us no heat, knew it from my mother’s face when a new child was born, knew it by contrasting the kitchens in which my mother was employed with our kitchen, knew it from the kind of desperate miasma in which you grow up learning that you have been born to be despised. Forever.

It remains impossible to describe the Byzantine labyrinth black people find themselves in when they attempt to save their children. A high school diploma, which had almost no meaning in my day, nevertheless suggested that you had been to school. But today it operates merely as a credential for jobs—for the most part nonexistent—that demand virtually nothing in the way of education. And the attendance certificate merely states that you have been through school without having managed to learn anything.

The educational system of this country is, in short, designed to destroy the black child. It does not matter whether it destroys him by stoning him in the ghetto or by driving him mad in the isolation of Harvard. And whoever has survived this crucible is a witness to the power of the Republic’s educational system.

It is an absolute wonder and an overwhelming witness to the power of the human spirit that any black person in this country has managed to become, in any way whatever, educated. The miracle is that some have stepped out of the rags of the Republic’s definitions to assume the great burden and glory of their humanity and of their responsibility for one another. It is an extraordinary achievement to be trapped in the dungeon of color and to dare to shake down its walls and to step out of it, leaving the jailhouse keeper in the rubble.

But for the black man with the attaché case, or for the black boy on the needle, it has always been the intention of the Republic to promulgate and guarantee his dependence on this Republic. For although one cannot really be educated to believe a lie, one can be forced to surrender to it.

And there is, after all, no reason not to be dependent on one’s country or, at least, to maintain a viable and fruitful relationship with it. But this is not possible if you see your country and your country does not see you, it is not possible if the entire effort of your countrymen is an attempt to destroy your sense of reality.

This is an election year, I am standing in the streets of Harlem. Newark, or Watts, and I have been asked a question.

Now, what am I to say concerning the presidential candidates, season after ignoble season? Carter has learned to sing Let my people go, speaking of the hostages in Iran, while taking no responsibility at all for the political prisoners all over his home state of Georgia. He is prepared for massive retaliation against the Ayatollah Khomeini but, after Miami, can only assure the city’s blacks that violence is not the answer. This despite the fact that in the event of “massive retaliation,” blacks will assuredly be sent to fight in Iran—and for what? Despite the news of the acquittal of the four Miami policemen who beat the black man McDuffie to death. That news made page 24 of The New York Times. The uprising resulting from the acquittal made page one.

The ghetto man, woman, or child who may already wonder why curbing inflation means starving him out of existence (or into the Army) may also wonder why violence is right for Carter, or for any other white man, but wrong for the black man. The ghetto people I am talking to, or about, are not at all stupid, and if I lie to them, how can I teach them?

Dark days. Recently I was back in the South, more than a quarter of a century after the Supreme Court decision that outlawed segregation in the Republic’s schools, a decision to be implemented with “all deliberate speed.” My friends with whom I had worked and walked in those dark days are no longer in their teens, or even their thirties. Their children are now as old as their parents were then, and, obviously, some of my comrades are now roughly as old as I, and I am facing sixty. Dark days, for we know how much there is to be done and how unlikely it is that we will live another sixty years. We know, for that matter, how utterly improbable it is—indeed, miraculous—that we can still have a drink, or a pork chop, or a laugh together.

I walked into an Alabama courtroom, in Birmingham, where my old friend the Reverend Fred Shultlesworth was sitting. I had not seen him in more than twenty years: his church was bombed shortly after I last saw him. Now, something like twenty-two years later, the man accused of bombing the church was on trial. The Reverend Shuttlesworth was very cool, much cooler than I, given that the trial had been delayed twenty- two years. How slowly the mills of justice grind if one is black. What in the world can possibly happen in the mind and heart of a black student, observing, who must stumble out of this courtroom and back to Yale?

It was a desegregated!!) courtroom, and it was certainly a mock trial. The only reason the defendant, J. B. Stoner, was not legally, openly acquitted was that the jury—mostly women, and one exceedingly visible black man dressed in a canary-colored suit (I had the feeling that no one ever addressed a word to him)—could not quite endorse Stoner’s conviction (among his many others about blacks) that being born a Jew should be made a crime “punishable by death—legally .”(He hastened to add, “I’m against illegal violence.”) Forced to admit—by the reading of newspaper quotes—that he had crowed, upon hearing of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.. “Well, he’s a good n*gger now,” Stoner said. “Hell, that ain’t got nothing to do with violence. The man was already dead.”

He was not acquitted, but he received the minimum sentence—ten years—and is free on bail.

If I put this travesty back to back with the case of—for example—the Wilmington Ten. I will begin to suggest to my students the meaning of education.

On the first day of class last winter at Bowling Green State University, where I was a visiting writer-in-residence, one of my white students, in a racially mixed class, asked me, “Why does the white hate the n*gger?”

I was caught off guard. I simply had not had the courage to open the subject right away. I underestimated the children, and I am afraid that most of the middle-aged do. The subject. I confess, frightened me, and it would never have occurred to me to throw it at them so nakedly. No doubt, since I am not totally abject, I would have found a way to discuss what we refer to as interracial tension. What my students made me realize (and I consider myself eternally in their debt) was that the notion of interracial tension hides a multitude of delusions and is, in sum, a cowardly academic formulation. In the ensuing discussion the children, very soon, did not need me at all, except as a vaguely benign adult presence. They began talking to one another, and they were not talking about race. They were talking of their desire to know one another, their need to know one another: each was trying to enter into the experience of the other. The exchanges were sharp and remarkably candid. but never fogged by an unadmitted fear or hostility. They were trying to become whole. They were trying to put themselves and their country together. They would be facing hard choices when they left this academy. And why was it a condition of American life that they would then be forced to be strangers?

The reality, the depth, and the persistence of the delusion of white supremacy in this country causes any real concept of education to be as remote, and as much to be feared, as change or freedom itself. What black men here have always known is now- beginning to be clear all over the world. Whatever it is that white Americans want, it is not freedom—neither for themselves nor for others.

It’s you who’ll have the blues. Langston Hughes said, not me. Just wait and see.

Esquire, October 1980