The subject of sex is so surrounded by superstitions and taboos that I approach it with trepidation. I fear lest those readers who have hitherto accepted my principles may suspect them when they are applied in this sphere; they may have admitted readily enough that fearlessness and freedom are good for a child, and yet desire, where sex is concerned, to impose slavery and terror. I cannot so limit principles which I believe to be sound, and I shall treat sex exactly as I have treated the other impulses which make up a human character.

There is one respect in which, quite independently of taboos, sex is peculiar, and that is the late ripening of the instinct. It is true, as the psycho-analysts have pointed out (though with considerable exaggeration), that the instinct is not absent in childhood. But its childish manifestations are different from those of adult life, and its strength is much less, and it is physically impossible for a boy to indulge it in the adult manner. Puberty remains an important emotional crisis, thrust into the middle of intellectual education, and causing disturbances which raise difficult problems for the educator. Many of these problems I shall not attempt to discuss 5 it is chiefly what should be done before puberty that I propose to consider. It is in this respect that educational reform is most needed, especially in very early childhood. Although I disagree with the Freudians in many particulars, I think they have done a very valuable service in pointing out the nervous disorders produced in later life by wrong handling of young children in matters connected with sex. Their work has already produced wide-spread beneficial results in this respect, but there is still a mass of prejudice to be overcome. The difficulty is, of course, greatly increased by the practice of leaving children, during their first years, largely in the hands of totally uneducated women, who cannot be expected to know, still less to believe, what has been said by learned men in the long words necessary to escape prosecution for obscenity.

Taking our problems in chronological order, the first that confronts mothers and nurses is that of masturbation. Competent authorities state that this practice is all but universal among boys and girls in their second and third years, but usually ceases of itself a little later on. Sometimes it is rendered more pronounced by some definite physical irritation which can be removed. (It is not my province to go into medical details.) But it usually exists even in the absence of such special reasons. It has been the custom to view it with horror, and to use dreadful threats with a view to stopping it. As a rule these threats do not succeed, although they are believed; the result is that the child lives in an agony of apprehension, which presently becomes dissociated from its original cause (now repressed into the unconscious), but remains to produce nightmares, nervousness, delusions and insane terrors. Left to itself, infantile masturbation has, apparently, no bad effect upon health1, and no discoverable bad effect upon character; the bad effects which have been observed in both respects are, it seems, wholly attributable to attempts to stop it. Even if it were harmful, it would be unwise to issue a prohibition which is not going to be observed; and from the nature of the case, it is impossible to make sure that the child will not continue after you have forbidden him to do so. If you do nothing, the probability is that the practice will soon be discontinued. But if you do anything, you make it much less likely that it will cease, and you lay the foundation of terrible nervous disorders. Therefore, difficult as it may be, the child should be let alone in this respect. I do not mean that you should abstain from methods other than prohibition, in so far as they are available. Let him be sleepy when he goes to bed, so that he will not lie awake long. Let him have some favourite toy in bed, which may distract his attention. Such methods are quite unobjectionable. But if they fail, do not resort to prohibition, or even call his attention to the fact that he indulges in the practice. Then it will probably cease of itself.

Sexual curiosity normally begins during the third year, in the shape of an interest in the physical differences between men and women, and between adults and children. By nature, this curiosity has no special quality in early childhood, but is simply a part of general curiosity. The special quality which it is found to have in children who are being conventionally brought up is due to the grown-up practice of making mysteries. When there is no mystery, the curiosity dies down as soon as it is satisfied. A child should, from the first, be allowed to see his parents and brothers and sisters without their clothes whenever it so happens naturally. No fuss should be made either way; he should simply not know that people have feelings about nudity. (Of course, later on he will have to know.) It will be found that the child presently notices the differences between his father and mother, and connects them with the differences between brothers and sisters. But as soon as the subject has been explored to this extent, it becomes uninteresting, like a cupboard that is often open. Of course, any questions the child may ask during this period must be answered just as questions on other topics would be answered.

Answering questions is a major part of sex education. Two rules cover the ground. First, always give a truthful answer to a question; secondly, regard sex knowledge as exactly like any other knowledge. If the child asks you an intelligent question about the sun or the moon or the clouds, or about motor-cars or steam- engines, you are pleased, and you tell him as much as he can take in. This answering of questions is a very large part of early education. But if he asks you a question connected with sex, you will be tempted to say, “hush, hush”. If you have learnt not to do that, you will still answer briefly and dryly, perhaps with a trifle of embarrassment in your manner. The child at once notices the nuance, and you have laid the foundations of prurience. You must answer with just the same fulness and naturalness as if the question had been about something else. Do not allow yourself to feel, even unconsciously, that there is something horrid and dirty about sex. If you do, your feeling will communicate itself to him. He will think, necessarily, that there is something nasty in the relations of his parents; later on, he will conclude that they think ill of the behaviour which led to his existence. Such feelings in youth make happy instinctive emotions almost impossible, not only in youth, but in adult life also.

If the child has a brother or sister born when he is old enough to ask questions about it, say after the age of three, tell him that the child grew in his mother’s body, and tell him that he grew in the same way. Let him see his mother suckling the child, and be told that the same thing happened to him. All this, like everything else connected with sex, must be told without solemnity, in a purely scientific spirit. The child must not be talked to about “the mysterious and sacred functions of motherhood”; the whole thing must be utterly matter-of-fact.

If no addition to the family occurs when the child is old enough to ask questions about it, the subject is likely to arise out of being told “that happened before you were born”. I find my boy still hardly able to grasp that there was a time when he did not exist; if I talk to him about the building of the Pyramids or some such topic, he always wants to know what he was doing then, and is merely puzzled when he is told that he did not exist. Sooner or later he will want to know what “being born” means, and then we shall tell him.

The share of the father in generation is less likely to come up naturally in answer to questions, unless the child lives on a farm. But it is very important that the child should know of this first from parents or teacher, not from children whom bad education has made nasty. I remember vividly being told all about it by another boy when I was twelve years old 5 the whole thing was treated in a ribald spirit, as a topic for obscene jokes. That was the normal experience of boys in my generation. It followed naturally that the vast majority continued through life to think sex comic and nasty, with the result that they could not respect a woman with whom they had intercourse, even though she were the mother of their children. Parents pursued a cowardly policy of trusting to luck, although fathers must have remembered how they gained their first knowledge. How it can have been supposed that such a system helped sanity or sound morals, I cannot imagine. Sex must be treated from the first as natural, delightful and decent. To do otherwise is to poison the relations of men and women, parents and children. Sex is at its best between a father and mother who love each other and their children. It is far better that children should first know of sex in the relations of their parents than that they should derive their first impressions from ribaldry. It is particularly bad that they should discover sex between their parents as a guilty secret which has been concealed from them.

If there were no likelihood of being taught badly about sex by other children, the matter could be left to the natural operation of the child’s curiosity, and parents could confine themselves to answering questions—always provided that everything became known before puberty. This, of course, is absolutely essential. It is a cruel thing to let a boy or girl be overtaken by the physical and emotional changes of that time without preparation, and possibly with the feeling of being attacked by some dreadful disease. Moreover, the whole subject of sex, after puberty, is so electric that a boy or girl cannot listen in a scientific spirit, which is perfectly possible at an earlier age. Therefore, quite apart from the possibility of nasty talk, a boy or girl should know the nature of the sexual act before attaining puberty.

How long before this the information should be given depends upon circumstances. An inquisitive and intellectually active child must be told sooner than a sluggish child. There must at no time be unsatisfied curiosity. However young the child may be, he must be told if he asks. And his parents’ manner must be such that he will ask if he wants to know. But if he does not ask spontaneously, he must in any case be told before the age of ten, for fear of being first told by others in a bad way. It may therefore be desirable to stimulate his curiosity by instruction about generation in plants and animals. There must not be a solemn occasion, a clearing of the throat, and an exordium: “Now, my boy, I am going to tell you something that it is time for you to know.” The whole thing must be ordinary and every-day. That is why it comes best in answer to questions.

I suppose it is unnecessary at this date to argue that boys and girls must be treated alike. When I was young, it was still quite common for a “well-brought-up” girl to marry before knowing anything about the nature of marriage, and to have to learn it from her husband; but I have not often heard of such a thing in recent years. I think most people recognize nowadays that a virtue dependent upon ignorance is worthless, and that girls have the same right to knowledge as boys. If there are any who still fail to recognize this, they are not likely to read the present work, so that it is not worth while to argue with them.

I do not propose to discuss the teaching of sexual morality in the narrower sense. This is a matter as to which a variety of opinions exist. Christians differ from Mohammedans, Catholics from Protestants who tolerate divorce, freethinkers from medievalists. Parents will all wish their children taught the particular brand of sexual morality in which they believe themselves, and I should not wish the State to interfere with them. But without going into vexed questions, there is a good deal that might be common ground.

There is first of all hygiene. Young people must know about venereal disease before they run the risk of it. They should be taught about it truthfully, without the exaggerations which some people practise in the interests of morals. They should learn both how to avoid it, and how to cure it. It is a mistake to give only such instruction as is needed by the perfectly virtuous, and to regard the misfortunes which happen to others as a just punishment of sin. We might as well refuse to help a man who has been injured in a motoring accident, on the ground that careless driving is a sin. Moreover, in the one case as in the other, the punishment may fall upon the innocent; no one can maintain that children born with syphilis are wicked, any more than that a man is wicked if a careless motorist runs over him.

Young people should be led to realize that it is a very serious matter to have a child, and that it should not be undertaken unless the child has a reasonable prospect of health and happiness. The traditional view was that, within marriage, it is always justifiable to have children, even if they come so fast that the mother’s health is ruined, even if the children are diseased or insane, even if there is no prospect of their having enough to eat. This view is now only maintained by heartless dogmatists, who think that everything disgraceful to humanity redounds to the glory of God. People who care for children, or do not enjoy inflicting misery upon the helpless, rebel against the ruthless dogmas which justify this cruelty. A care for the rights and importance of children, with all that is implied, should be an essential part of moral education.

Girls should be taught to expect that one day they are likely to be mothers, and they should acquire some rudiments of the knowledge that may be useful to them in that capacity. Of course both boys and girls ought to learn something of physiology and something of hygiene. It should be made clear that no one can be a good parent without parental affection, but that even with parental affection a great deal of knowledge is required as well. Instinct without knowledge is as inadequate in dealing with children as knowledge without instinct. The more the necessity of knowledge is understood, the more intelligent women will feel attracted to motherhood. At present, many highly educated women despise it, thinking that it does not give scope for the exercise of their intellectual faculties 5 this is a great misfortune, since they are capable of being the best mothers, if their thoughts were turned in that direction.

One other thing is essential in teaching about sex-love. Jealousy must not be regarded as a justifiable insistence upon rights, but as a misfortune to the one who feels it and a wrong towards its object. Where possessive elements intrude upon love, it loses its vivifying power and eats up personality 5 where they are absent, it fulfils personality and brings a greater intensity of life. In former days, parents ruined their relations with their children by preaching love as a duty; husbands and wives still too often ruin their relations to each other by the same mistake. Love cannot be a duty, because it is not subject to the will. It is a gift from heaven, the best that heaven has to bestow. Those who shut it up in a cage destroy the beauty and joy which it can only display while it is free and spontaneous. Here, again, fear is the enemy. He who fears to lose what makes the happiness of his life has already lost it. In this, as in other things, fearlessness is the essence of wisdom.

For this reason, in teaching my own children, I shall try to prevent them from learning a moral code which I regard as harmful. Some people who themselves hold liberal views are willing that their children shall first acquire conventional morals, and become emancipated only later, if at all. I cannot agree to this, because I hold that the traditional code not only forbids what is innocent, but also commends what is harmful. Those who have been taught conventionally will almost inevitably believe themselves justified in indulging jealousy when occasion arises; moreover they will probably be obsessed by sex either positively or negatively. I shall not teach that faithfulness to our partner through life is in any way desirable, or that a permanent marriage should be regarded as excluding temporary episodes. So long as jealousy is regarded as virtuous, such episodes cause grave friction ; but they do not do so where a less restrictive morality is accepted on both sides. Relations involving children should be permanent if possible, but should not necessarily on that account be exclusive. Where there is mutual freedom and no pecuniary motive, love is good; where these conditions fail, it may often be bad. It is because they fail so frequently in the conventional marriage that a morality which is positive rather than restrictive, based upon hope rather than fear, is compelled, if it is logical, to disagree with the received code in matters of sex. And there can be no excuse for allowing our children to be taught a morality which we ourselves believe to be pernicious.

Finally, the attitude displayed by parents and teachers towards sex should be scientific, not emotional or dogmatic. For example, when it is said of a mother speaking to her daughter; “Let her tell nature’s plan, in a spirit of reverence”; and of a father instructing his son: “The father should, in a spirit of reverence, explain nature’s plan for the starting of a new life”—such sayings may be passed over by the reader as embodying nothing questionable. But to my mind there should be no more occasion for “reverence” than in explaining the construction of ’a steam-engine. “Reverence” means a special tone of voice from which the boy or girl infers that there is some peculiar quality about sex. From this to prurience and indecency is only a step. We shall never secure decency in matters of sex until we cease to treat the subject as different from any other. It follows that we must not advance dogmas for which there is no evidence, and which most impartial students question, such as: “After maturity is reached the ideal social relationship of the sexes is monogamous wedlock, to which relationship both parties should live in absolute fidelity” (ib. p. 310). This proposition may or may not be true; at present there is certainly no evidence sufficient to prove it true. By teaching it as something unquestionable, we abandon the scientific attitude, and do what we can to inhibit rational thought upon a most important matter. So long as this dogmatism persists in teachers, it is not to be hoped that their pupils will apply reason to any question upon which they feel strongly. And the only alternative to reason is violence.

NOTES

1 In very rare instances, it does a little harm, but this is easily cured and is not more serious than the results of thumb-sucking.

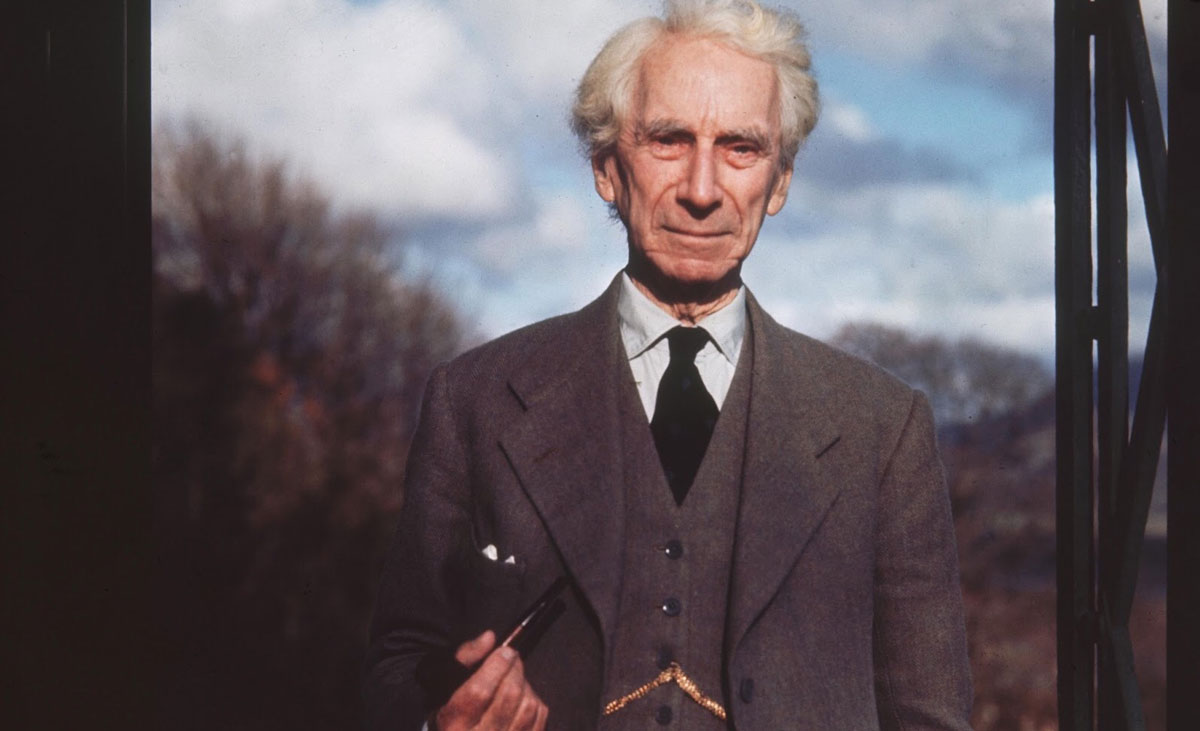

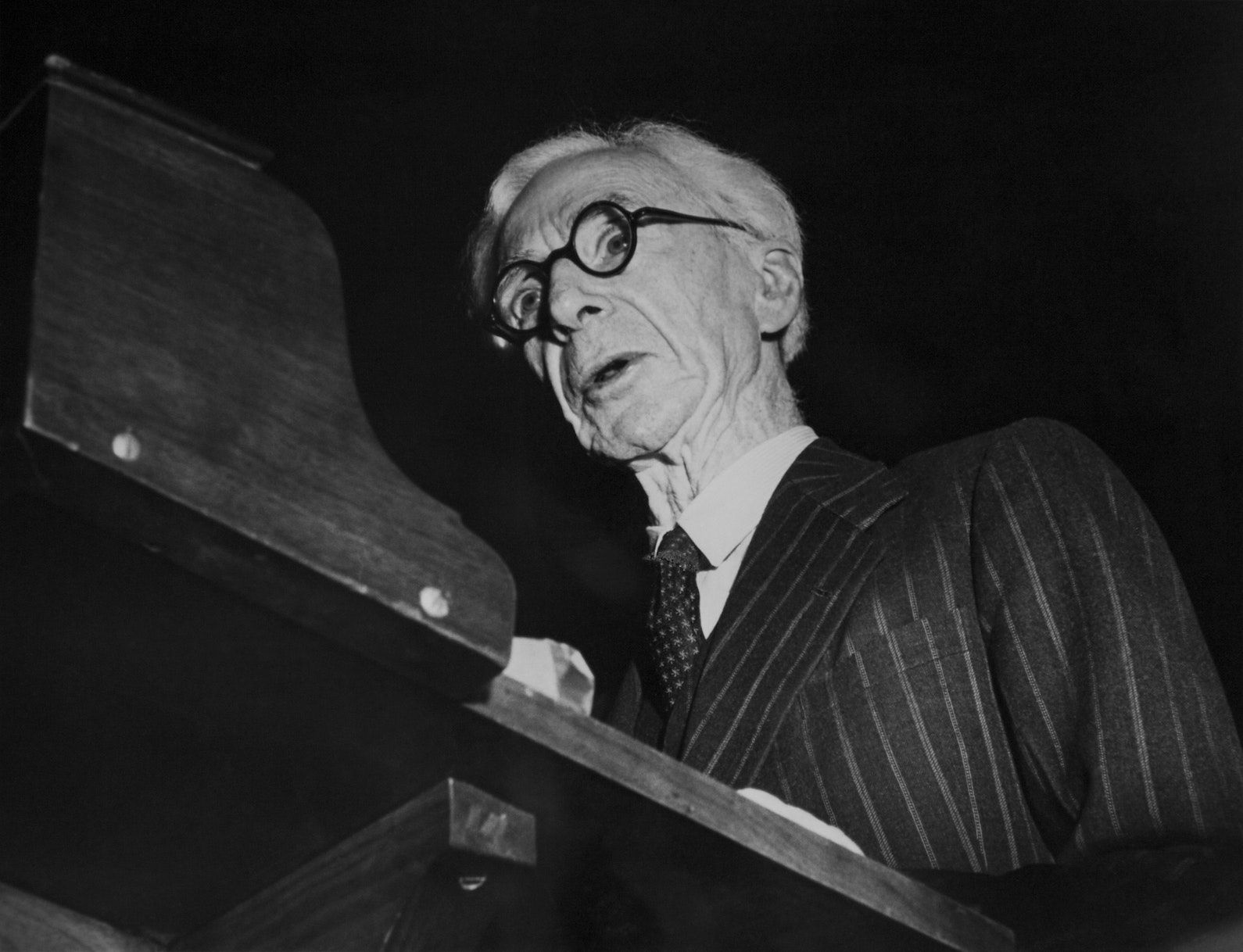

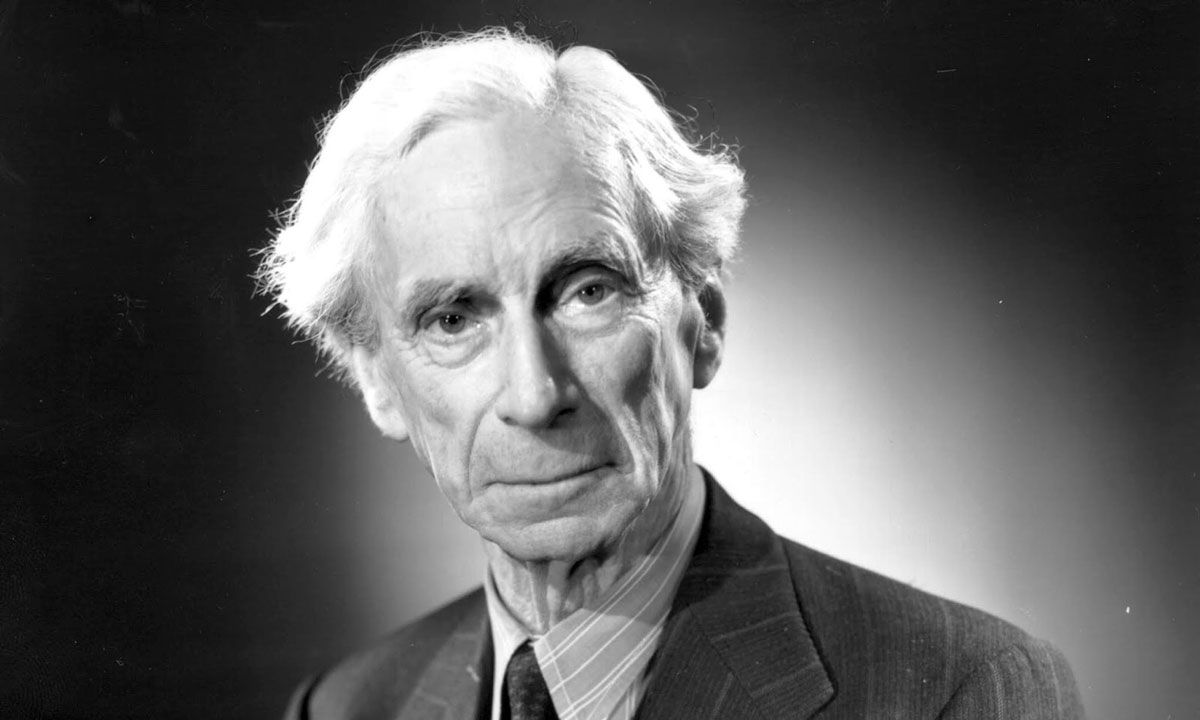

SOURCE: Bertrand Russell, Education and the Good Life (1926); pp. 209-223