Marcello Veneziani’s article explores the century-old discussion about the West’s decline, initiated by Oswald Spengler’s significant yet misleading work, The Decline of the West. Veneziani challenges the idea that the West, especially after World War I, was in decline, instead suggesting that this era heralded the onset of what became known as the American Century, marked by the Westernization and, later, the Americanization of the world. However, as the 20th century ended, globalization emerged as the successor to Westernization, now showing signs of disintegration amid advancements in technology, economic conflicts, and a retreat into a new form of cold war on the political-military front. Veneziani revisits Spengler’s forecasts and insights into the dynamics of civilizations, the supremacy of technology, and the eventual clash between financial systems and political will, offering a thoughtful examination of history’s cyclical nature and Spengler’s lasting influence on the narrative of Western civilization’s path and its interplay with globalization.

* * *

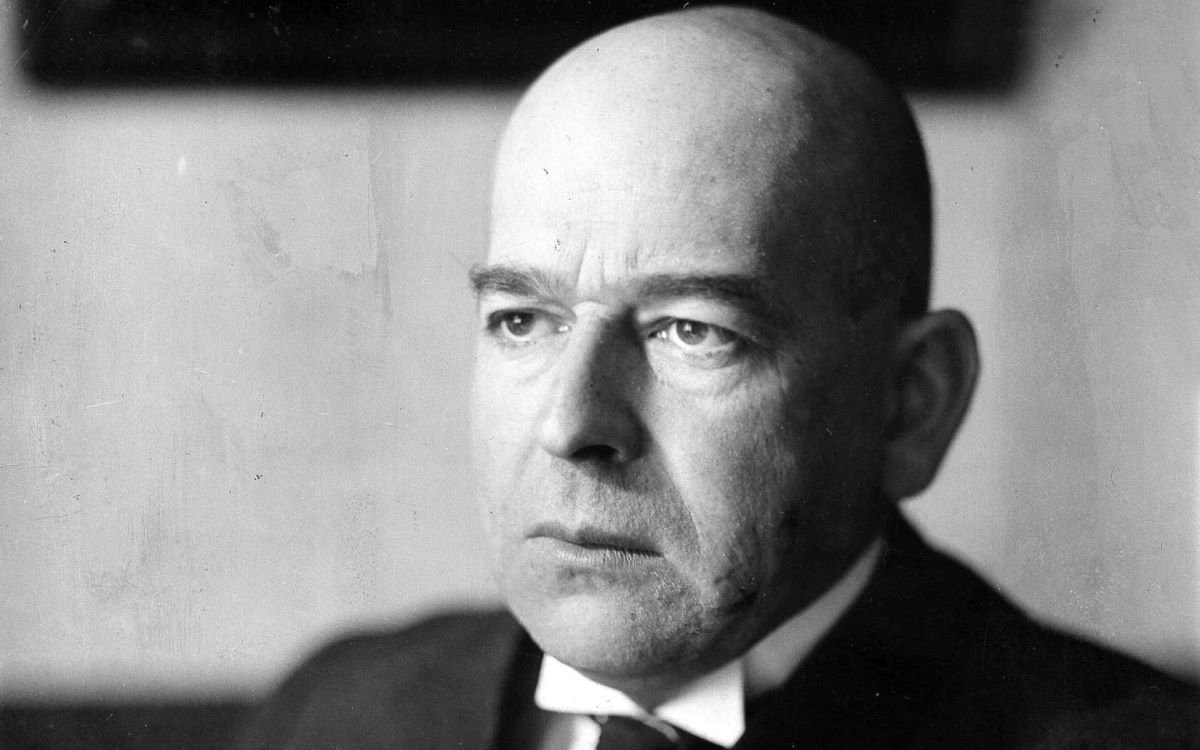

The claim of the West’s decline, proclaimed for a century now, originated from a work with a grandiose and misleading title, The Decline of the West. Its grandeur lay not just in its success or its timely publication after World War I, but in its world vision, historical and dramatic framework, analogies and comparisons, and the broad morphology of civilizations sketched by its author, Oswald Spengler.

However, the title was misleading because the West did not decline after World War I; Europe as the world’s center did, as did the Central Empires, but the West did not. Instead, what later came to be known as the American Century began, marked by two wars and pervasive cultural and commercial colonization of the planet, ahead of any military presence. The 20th century was the era of the world’s Westernization, which essentially meant the Americanization of the globe. With the end of the 20th century, globalization replaced Westernization. Today, there’s a perception that globalization is crumbling: continuing in technology, fracturing in the marketplace amid economic conflicts, and retreating politically and militarily into a multipolar cold war among various powers and impotencies.

It was 1914 when Oswald Spengler concluded The Decline of the West; the title then became a post-war epitaph and the backdrop for cultural pessimism or crisis thought. The work was published towards the end of World War I and was a triumph in sales and commentary. Delayed by the war, this allowed Spengler to revise the text. For the future, Spengler predicted the final conflict between the dictatorship of money, technology, and finance, and the civilization of blood, labor, and socialism. Eventually, he prophesied, the sword would triumph over money because only a power can overturn another power. His prophecy was accurate in the short term: soon after, communism, fascism, and national socialism came to power. Spengler had foresight, but not the longest view. The revolt of blood against gold, of labor against capital, was swept away in the West by wars, tragedies, and failures. After the conflict between politics and economy, money continued to reign supreme. But behind money, Spengler noted, it’s technology that initially serves the Faustian man but then subjugates him. The dominance of technology, Spengler predicted, “will also dethrone God.” To man and technology, Spengler dedicated an insightful essay, parallel and diverging from Ernst Jünger’s The Worker which appeared shortly after, and from Heidegger’s reflections on technology. Spengler was prophetic when he foresaw a final conflict between the dictatorial financial system and the caesarism of political will, yet he did not hide his admiration for technical-financial caesarism and its soldiers: engineers, inventors, entrepreneurs, financiers. He believed philosophers were pitiful compared to managers and financial lords; “any line not written for action seems superfluous to me.” He went as far as preferring “a Roman aqueduct over all the temples and statues of Rome.”

For Spengler, history is a constellation of concluded worlds called civilizations, each obeying its value system and fate in strict determinism; but each system is relative to others and to times; and has a trajectory: dawn, zenith, and twilight. A civilization is absolute within itself, but not eternal. Thus, the sense of destiny flips into its opposite, into historical relativism and social Darwinism, the ethics of loyalty turn into titanism, anti-rationalist vitalism becomes pure activism, and caesarism, detached from the sacred empire, becomes mere will to power.

Like the Marxists, for Spengler theory served practice, thought served history. The common matrix lies in Goethe’s Faust: “In the beginning was the deed.” In Marx, revolutionary subjectivism takes shape in the name of Prometheus, in Spengler heroic subjectivism in the name of Faust and his civilization. But when the revolt of blood against gold took shape in Germany with National Socialism, Spengler distanced himself from Hitler and his party: “We wanted to rid ourselves of parties, but the worst remained.” He saw racism as “an ideology of resentment towards Jewish superiority” and indicative of “spiritual poverty,” and criticized Rosenberg’s work. He lost his following because he died in ’36. In turn, Hitler did not profess to be a follower of Spengler and rejected the idea of the Decline of the West. The Nazi regime, on Goebbels’ orders, opposed the philosopher. Meanwhile, Spengler received great reception in Fascist Italy, for which he had a positive view expressed also in admired dedications to its leader. Mussolini read Spengler, reviewed him, had Years of Decision translated, and, as Renzo De Felice noted, became increasingly Spenglerian even in controversy with Nazi Germany. He found in Spengler the praise of young peoples, the Mediterranean spirit, and Romanity.

Spengler reminded his critics that “Decline” meant not apocalypse but fulfillment: the West sets in its fulfillment, in the arms of globalization. He concluded his work in the spirit of heroic fatalism (ducunt fata volentem, nolentem trahunt,* are the concluding words of the Decline). Memorable remains the figure of the Pompeii sentinel Spengler evoked in Man and Technics, who dies in the eruption of Vesuvius because he was not relieved from his post. Spengler sought to translate Nietzsche’s thought and Goethe’s vision into historical terms; he took Zarathustra to battle, bringing into history the Will to Power, the Eternal Return, the Superman, Faust, and the amor fati.

“Nietzsche’s cunning monkey,” “the ingenious charlatan,” “the dilettante,” “the gloomy one,” “the hyena,” “the prophet of doom”: these derogatory definitions of Spengler were by Thomas Mann, Benedetto Croce, Ernst Cassirer, György Lukács.

Spengler was a tragic thinker, and to pessimism, he dedicated an intense essay; a historical pessimism prelude to heroic fatalism. Spengler was a pessimist in disposition before thought. Behind the Prussian hardness and the praise of steel beat a delicate heart, prone to tears, of frail health, as revealed in his autobiographical writing A Me Stesso** [To Myself]. Spengler remained the prophet of the West’s decay, sang the glory of sunsets and the honor of defeats.

La Verità, April 5, 2024

* Fate leads the willing and drags the unwilling

** Published for the first time in Italy by Adelphi in 1993. It is unpublished even in German.