While Wim Wenders’ latest film, Perfect Days, is still in theaters, it’s certainly worth revisiting a nearly forty-year-old work of his, a documentary that is also a journey of revelation and discovery into Japanese culture, specifically its capital Tokyo, through the eyes of an attentive, respectful traveler, always ready to open up to new worlds. And, on that path, to delve into the deepest sense, be it artistic, personal, or philosophical-religious, of the figure of Ozu Yasujiro, a director who for Wenders has been and is a true Father. If Perfect Days struck a chord with you, then Tokyo-ga is a must-watch, promising to be a delightful experience. Meanwhile, we re-present the review that Adriano Piccardi once wrote for the Italian film magazine “Cineform” in April 1986.

* * *

There Was a Father

by Adriano Piccardi

Tokyo-ga is a part of a series of diary-like films that Wim Wenders has created in recent years, offering his impressions of the Japanese capital and director Yasujiro Ozu. While visiting places and people in Tokyo, Wenders speaks about Ozu: “His films always tell, with means reduced to the bare essentials, about the same people in the same city: Tokyo. This chronicle, covering the last forty years, records the metamorphosis of life in Japan.”

Tokyo-ga unfolds and moves within a question of fundamental importance in the history of art, and culture in general: What is the boundary (a point of separation but equally, of contact) between love (devotion, gratitude: “filial” love) and betrayal? The idea that betrayal is an undoubtedly necessary step in the formation of any tradition might now be a well-acknowledged truth. However, it is equally beneficial to explore the conditions that determine its clear manifestation in various fields (such as in expression). Cinema, by its very nature, binds the universe of its symbols to the materiality of the real world. Even when it is artfully molded within those thrilling construction boxes known as studios and soundstages, it cannot be denied that: 1) it is the elements of a “reality” (recognizable, conventionally accepted even in its most idealized forms or, conversely, distorted) that are reconstructed; 2) it is materially the things, the objects, reality or its reconstructed double that transform, through the impression on film, into symbols, and thus into signs of a language. The extent of betrayals that make up, in their succession, the tradition, and hence the history, of cinema as a potential map of authors, should always be traced also through the changes in reality (geographical, urban, social, media-related, familial, etc.) that have characterized its generational progression.”

The fact that one of these authors, yet again in his filmography, embraces this quest only reaffirms the innate passion of his reflection, and the consciousness shaping the progression of his phases. Wim Wenders’ body of work mirrors a dual “settling of scores”, offering evidence of a double, affectionate patricide: the culture (and cinema) of yesteryear’s Germany and, more significantly, of post-war USA are its targets. Regarding the latter, it’s the encounter between Wim Wenders and Nicholas Ray that marks the pinnacle (and certainly the most tragic) of this confrontation. However, until now, the opportunity for the German director to confront another looming “presence” intertwined with his cinema was missing: that of Yasujiro Ozu. A true presence/absence, since only after creating The Goalkeeper’s Fear of the Penalty could Wenders ascertain the closeness of his cinematic vision to that of the great Japanese director, who had passed away almost a decade earlier and whose work he had, until then, not seen.

The paradox at the heart of Ozu’s cinema is that it’s possible, through a meticulous crafting of cinematic signs that leaves nothing to chance and often bends “reality” to the will of a god-like director, to transform a narrative into an ongoing “documentary” (progressing film by film) about the cultural, ethical, and social upheavals that Japan faced from the decade before World War II up to the early 1960s. This ability to use the phantom of a story to ultimately deny it any chance of realization is also foundational to Wenders’ cinema. He, in turn, consciously pursues a blend of fiction and documentary, in a delicate and continuous unveiling of the shadowy zone that traditional narratives prefer to conceal, tending to deny its obviousness.

“If there were anything sacred in cinema, it would be for me the work of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. […] Ozu’s work doesn’t need my acknowledgment, and, besides, such a notion of cinema’s sacredness exists only in the imagination. My trip to Tokyo, therefore, had nothing to do with a pilgrimage. I was curious to see if I could still discover something from that era and if anything remained of that work, maybe some images or people; or if, in the twenty years since Ozu’s death, so much had changed in Tokyo and Japan that nothing of it could be found” (excerpt from the film’s script). So, it was about feeling the terrain. The quest undertaken in unfamiliar territory, based not on a remote experience of it, but on the acquaintance with an idea of it, provided by a defined repertoire of images. Like the protagonist of Alice in the Cities searching for a match between his imagination and a tangible reality, Wenders immersed himself in the city of Tokyo, armed with a camera to take notes and draw comparisons.

Capturing images from the given reality (places, objects, people, gestures) is to understand how much it has changed, and to recognize in this transformation the tangible necessity of betrayal. A “surface-level” endeavor? Wenders isn’t trying to say anything new about the Japanese megalopolis, but rather to filter through his own sensitivity and, above all, his motivations, images similar to those already familiar to him and us, in the direct experience of the reality underlying them.

Tokyo Chorus – A retranscription of certain signs was necessary to weave the narrative proposed in Tokyo-ga. A narrative that doesn’t aim to peak in the exemplarity of a reportage that enriches our knowledge about that distant, magmatic, and still, all things considered, enigmatic country, but is constructed in the reshuffling of these personal “postcards” with other images: frames from Tokyo Story (the indispensable presence of Ozu’s eye); shots that overtly seek the revelation of a return in certain urban landscape views; encounters with people whose lives have been irrevocably shaped by the Master; the striking moment when Wenders wants to experience and demonstrate in the practicality of practice the limit, the unsustainability of a total adaptation to the view of things that Ozu’s cinema embodied.

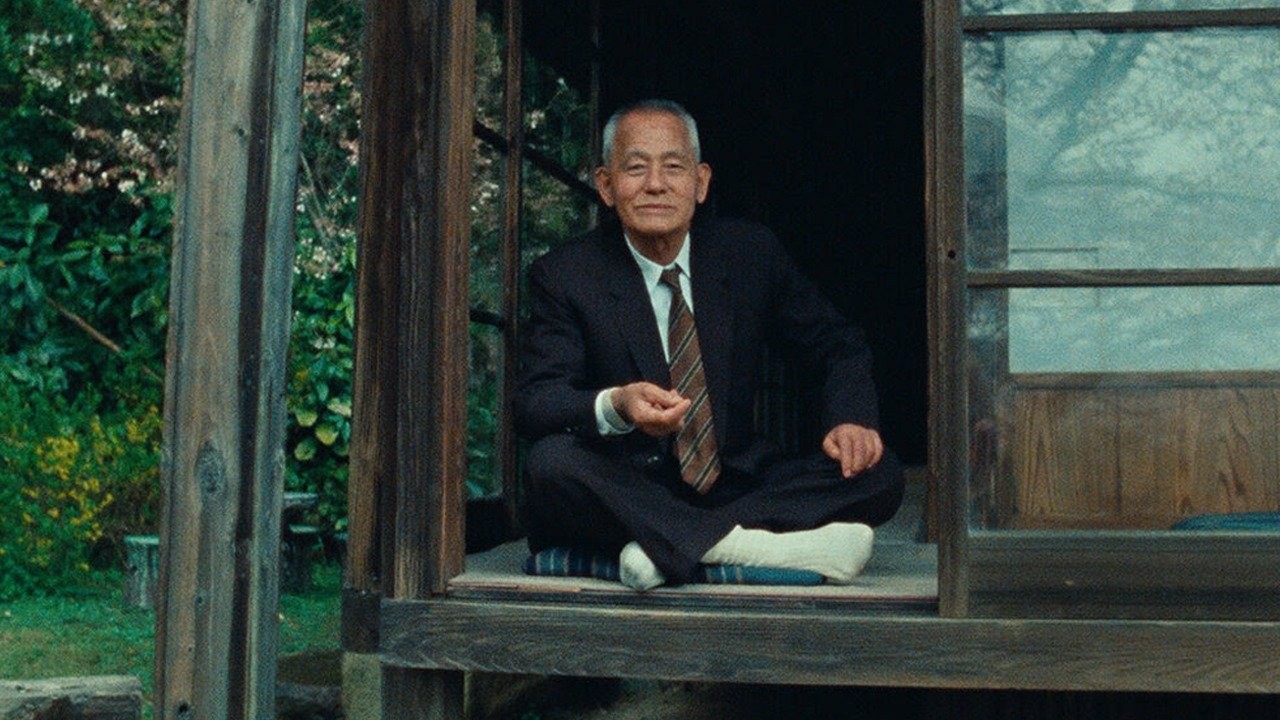

In the interplay of these diverse elements, a meta-cinematic meaning emerges, a “dialogue” between Wenders and the creator of the cinematic form whose enduring principles he sought to test. Once again, death is a constant presence, shadowing the establishment of this journey, as it did in the making of Nick’s Film. But whereas there the event was, so to speak, ongoing, only reaching its conclusion as the end of a boundary-pushing experience, here it is a given fact from the start, shaping the moves, the need for a detour that, through objects and people, tries to compensate for a fundamental absence: the missing “father” one wishes to personally interrogate. Accompanied by another “son” (and thus, for him, a kind of elective brother, an elder brother), Chishu Ryu, Wenders can only pause before a grave adorned with an “empty” symbol, like a gesture of reconciliation (or a hint in a certain direction) offered to his restless search. However, the stillness suggested by this symbol is not (and has never been) the subject of Wim Wenders’ cinema, starting from that decisive transgression of Peter Handke’s text, with which he concluded his version of The Goalkeeper’s Fear of the Penalty.

In Tokyo-ga, the meeting and dialogue with Werner Herzog affirm this inner condition, revealing the distinct relationship each director has with vision that nourishes their cinema. While Herzog seems now inclined towards a possibility of cinema only in the most ethereal atmosphere, in an absolute transparency that preserves the eye’s (the lens’s) adherence to the object of vision, Wenders, on the contrary, finds that the search for images can also unfold in the city, amid the teeming overlay of moving signs, where transparency (both of symbols and, materially, atmospheric) is but a vague memory, an aspiration, whose traces lead nowhere: yet it’s still important to go.

Then, Atsuta’s tears, while on one hand a moment of intense emotion, on the other measure the distance between the devoted cameraman and the German director: the former steadfast in his monastic vow that led him to refuse working with anyone else after the death of the author-father; the latter firmly resolved not to settle in any form of crystallized veneration, and to strengthen his love through repeated betrayal. It’s evident that, from this perspective, Wenders and Ryu are much closer, when the latter, Ozu’s manipulated fetish actor in about twenty films, confesses that now people recognize and stop him on the street because he’s the protagonist of a television series.

Wim Wenders’ cinema has always proceeded in response to its internal prompts, both formal and moral. In this respect, Tokyo-ga is not a “minor” work, despite certain characteristics (its placement in the author’s filmography, the reduced duration, the abandonment of even the slightest pretext of fiction in favor of pure documentary). This “notebook” of Japanese reflections is, on the contrary, an essential constitutive moment to the coherence of a production in perpetual motion, constantly seeking new boundaries to measure against, and equally engaged in continuous reflection on the motives of its own identity.

Cineforum, 253, April 1986