by Rolando Caputo

“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the Past.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

1935. “Noodles” (Robert De Niro) enters a Chinese theatre through a second-storey side-door. He pauses briefly to glance at the shadow puppet play below, then moves on to the opium den. A Chinaman takes his overcoat as Noodles sits on a shabby mattress, his face seemingly expressionless. As he toys with the ring on his finger, the Chinaman prepares the opium pipe. Noodles stretches out on the mattress, lying on his side, tie pulls a hemp mat under his head, takes the pipe and inhales, and. after several puffs, rolls on to his back. There is a change of camera angle to a high-angle, medium close-up; still expressionless, the face is finally broken open by a smile. Freeze frame. Seconds later, the end credits begin rolling, superimposed on De Niro’s smiling face. Approximately seven minutes of screen time, it is one of the most beautiful scenes ever produced by the cinema, and the last shot is as symbolically suggestive and mystifying as the famous close-up of Greta Garbo’s face at the end of Queen Christina (1933).

In the dozen or so film reviews I have read, this scene barely registers meaning. For Neil Jillett, the scene is surely proof of what he calls the film’s “pointless cleverness”1. For Meaghan Morris, the scene doesn’t exist at all; the ending for her comes in a prior sequence.

Still, even at the end Leone can combine De Niro with a garbage truck to create a few minutes of claustrophobic terror. It’s a fine conclusion for a pulp film saved only by its splendid flourishes of violence from its fate as a mere failed art.2

Even better, for Lyn McCarthy, the film “. . . begins and ends with an opium-induced dream sequence”3. The fact that the film does not begin with Noodles in the opium den or that there are no narrative shifters which indicate the dream mode seems irrelevant to McCarthy’s understanding of the film. Without being unfair, one could say then that the last scene of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America remains, for most reviewers, either unacknowledged or a bizarre coda, artlessly tacked on to a film with a less than conventional narrative structure.

The film’s narrative structure — the temporal interplay between the periods 1923, 1933 and 1968 — has itself come under significant criticism: “…. the unnecessary complications which the time shifts impose on the plot”4 or:

…there never seems to be arty special reason for any particular shift except pure art-effect — so it all becomes increasingly irksome and silly. It also makes the film fall apart into an array of loosely connected chunks.5

Much of the confusion about Once Upon a Time in America stems from a certain critical inability to understand why the film is structured the way it is, and why Leone chooses to conclude the fiction with such a supposedly enigmatic scene.

To address the issue of the film’s narrative structure and mise-en-scène first: Meaghan Morris, to her credit, is one of the few who attempts to set out cerrain literary antecedents for the film’s narrative presentation:

It is a type of narrative which almost forms a genre in itself as a broken-down version of the nineteenth century novel-saga of social and personal genesis, Its main literary practitioners today write high-class pot-boilers, like William Styron or John Fowles — and so it promised to be the perfect style for Leone to choose for a gangster dynasty story with a forty year span.6

The reference to Styron and Fowles implicitly connects Leone’s film to the pseudo-modernist narrative dramas of Sophie’s Choice and The French Lieutenant’s Woman, It would be more accurate to say that Leone’s film is an attempt to combine two distinct, but at limes interconnected, literary traditions represented within the American novel of the early 20th Century. One tradition is that associated with authors such as Jack London, Frank Norris and Thomas Wolfe: they wrote sagas about America’s birth as a nation, fictions poised between the old frontiers and the encroachment of civilization, the emergence of the great metropolises, of urban expansionism, commerce and the ethnic city dwellers. Given the magnitude of narrative scope, the novels are heavily plotted and excessively descriptive and, like the novels of John Dos Passos, there is always more or less a sense of social history inscribed within their fictions.

Within this context, it should be remembered that Leone’s original script of 10 or more years ago was entitled “Once Upon a Time, There Was America”; “America”, therefore, was to be the central character of the film. The above-mentioned authors, together with others such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, and the American cinema would furnish Leone with the visions necessary for him to orchestrate his own imaginary America. The eventual revision in the title suggests the partial displacement from the obsession with America to other themes.

The film most clearly invokes its literary antecedents in its meticulous recreation of the Jewish quarter in the Lower Fast side of New York in the 1920s. The art direction and photography combine to produce a mise-en-scène effect similar to that of a certain literary pictorial naturalism, dependent as it is on a highly descriptive style Linguistics makes it easy for literary theory to formulate a difference between the activity of description and narration (there is a whole literary practice based upon this difference; e.g., the novels of Alain Robbe-Grillet), Not so in the cinema, given that the image has the capacity to simultaneously render narration and description (when is an image solely narrational and non-descriptive?), and much of the descriptive potential of film resides in the area of art direction and mise-en-scène generally.

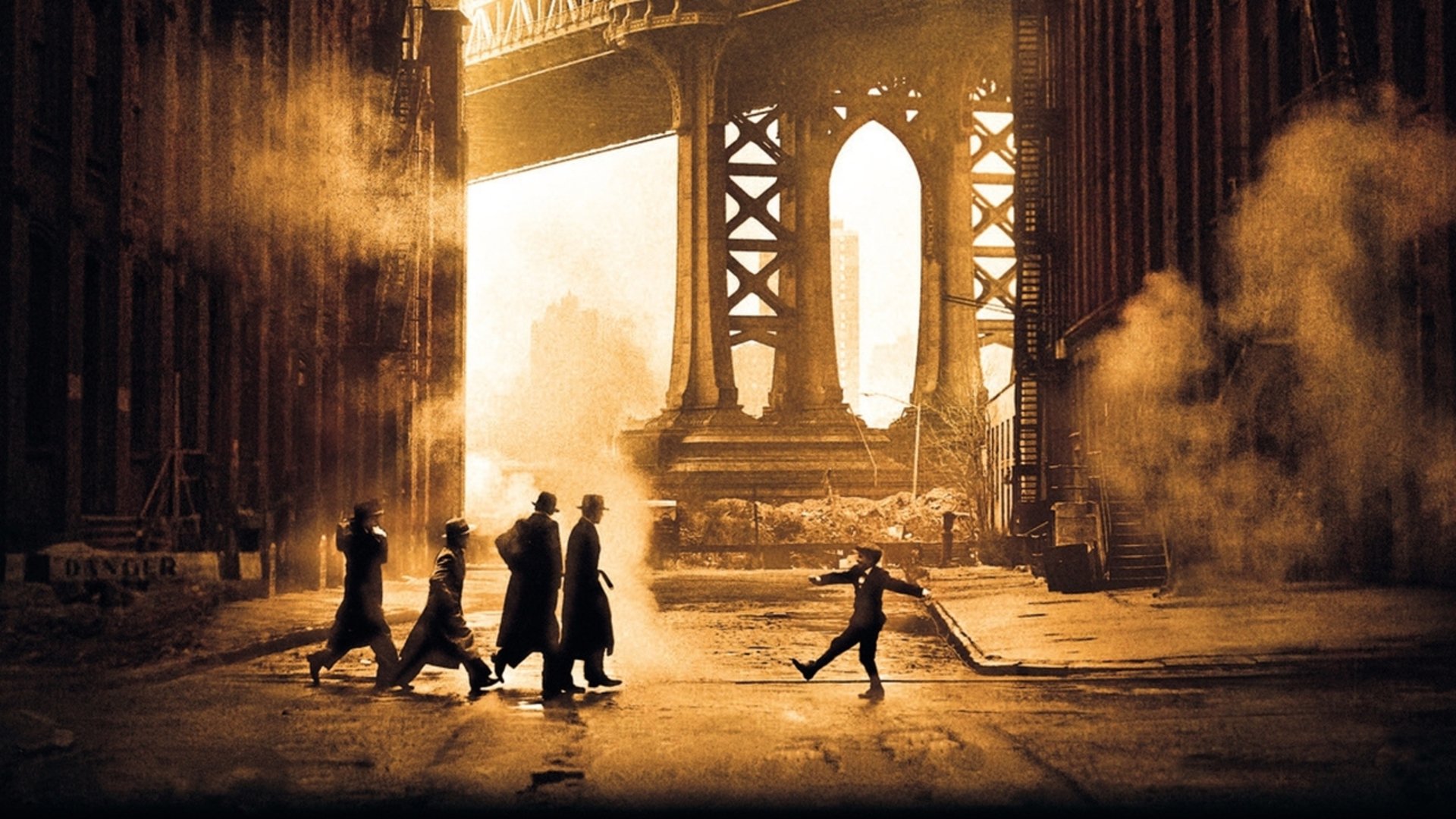

Leone wants to make full descriptive use of the extravagant art direction. The photography, therefore, is pushed to capture a grand-scale pictorialism through the repeated use of the wide-angle long shot, a framing device which places the childhood gang in the lower forefront of screen and, stretching behind them in depth of field the crowded streets and apartment buildings of the Jewish quarter or, in the now famous image of the film, places the gang, dwarf-like in scale, with the Brooklyn bridge in the background.

It is within the childhood sequence of the film that one feels the grand scale of the image composition is disproportionate, given the not-too- significant narrative events. While acknowledging that the art direction and set designs are of the highest standard, they only ever function as a descriptive backdrop to the narrative events: the characters’ movements are rarely orchestrated so as to make use of the spatial dimensions of the set designs (notice the absence of dolly shots which would allow the penetration of screen space). Finally, it should be noted that the 1920s’ period is the only temporally autonomous sequence in the film: that is, there are no temporal shifts to the other time periods within its 54-minute duration.

There is much in Leone’s excessive pictorialism, narrative duration, grand scale compositions, overt symbolism and stylistically baroque flourishes which remind one of Erich von Stroheim, certainly the von Stroheim of Greed (1923). Both directors refuse to sacrifice material for the sake of narrative economy.

Although the film can be faulted at times at the level of mise-en-scène, it succeeds, in turn, almost fully at the level of the narrative structuring of events. To invoke the second literary tradition drawn upon the film, its narrative structure can be called Faulknerian. William Faulkner’s novelistic devices such as narrative fragmentation, the non-linearity of story events, and the parallel articulation of past and present narrative tenses find a kind of filmic equivalent in Once Upon a Time in America. But, more important, is Faulkner’s use of repetition as a means through which characters and events acquire a progressively layered significance, just as in Leone’s film the repetition of events and objects produces a progressive addition of meaning. Given that the film is also a mystery story, it is another way to prevent the enigmas from being resolved until the very end. Given Leone’s comments on the film, it is clear that the narrative is as much of thematic concern as it is of structural concern:

Time and the years are an essential element in the film. In the course of them, the characters have changed, some rejecting their past identities and even their names. And yet, in spite of themselves, they have remained bound to the past and to the people they knew and were. They have gone separate ways. But, growing from the same embryo, as it were, after the careless self- confidence of youth, they are united again by the force that had made them enemies and driven them apart — time.7

Given the film’s epic dimension and Leone’s ambitiousness, one expects Once Upon a Time in America to be cluttered with grand themes and so it is: time, the past, and memory offer one duster of themes; the criminal underbelly of American capitalism, gangsterism, corruption and politics form another cluster; and so forth. But, finally, it seems these grand themes drift out of the film, as if they could never be fully integrated. The film settles (in the last hour) into its true themes: the shedding of innocence and how an individual lives with grief.

Loss of innocence (which does not mean the absence of guilt) for David “Noodles” Aaronson has to do with the clarity of understanding which the individual has acquired about his existence within a corrupt world. Perversely enough, Noodles’ innocence is manifested in his violent relation to people and events. He acts but does not think and, therefore, commits violence without moral culpability: for example, his stabbing of the police officer and his rape of Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern) and Carol (Tuesday Weld). Noodles’ innocence is fostered by an unquestioning, childish belief in the codes of masculine bonding — friendships cannot be betrayed — and this prevents him from realizing in advance Max’s (James Woods) twisted ambitions. The 1968 scenes with Deborah and Secretary Bailey (alias Max) mark the shedding of innocence about life and the past, the acquisition of knowledge and a kind of maturity which is affirmed in his denial of the past to Secretary Bailey. Noodles now understands and, in that understanding, he outstrips the possible violent response which the revelations demand. Which is not to say that Noodles forgives, but, as the scene with Secretary Bailey clearly indicates, Noodles is progressively detaching, withdrawing, from the emotional pull of the past — not easily, one must add, because there is much suppressed anguish in that scene.

There is much in De Niro’s characterization of the old Noodles which evokes a somnambulist’s behaviour. One can trace through the fiction a set of metaphors and motifs about sleep and death which traverse the character’s destiny. Most are obvious, given Leone’s predilection for overt symbolism: the outline of his body bullet-holed into the bed; Noodles’ making love in a coffin in the back of a hearse (driven by Max!); and, soon after his return to New York in 1968, Noodles is framed below a rising tombstone supported by a bulldozer. The torn-up gravestones are only another symbol of the return of the repressed, the past and reawakened memories.

If one thinks back to the 1933 scene, the viewer never sees Noodles leave New York; after buying a ticket to Buffalo, he pauses to contemplate his reflection and from that reflection emerges the Noodles of 1968. That single shot produces a temporal transition marking a 35-year ellipse. Diegetically, of course, Noodles does leave, but, metaphorically, the shot indicates a ‘time freeze’. Nothing of those 35 years is ever represented. It is as if he went nowhere and did nothing; a life without meaning is also a symbolic form of death. The metaphor of ‘frozen time’ also finds iconic representation: Noodles’ first words to “Fat” Moe on his return in 1968 are, “I brought back the keys to your clock.” Moe’s clock has not marked time for 35 years; the clock hands have remained frozen. Moe eventually rewinds the dock as if, with Noodles’ return, time can begin again.

The film’s coda — the final scene of Noodles in the opium den – offers a scene of purely metaphoric association and reveals fully the fate of Noodles in (hose 35 years of absence, the “dead time” in his life and in the film. The (mistaken) guilt and grief Noodles feels after the death of his friends can only but turn him into a “sleeping corpse” — a retreat from life into oblivion. Time and grief have made a sleepwalker of Noodles, and that is the Noodles summoned to New York in 1968. In an exchange of dialogue which can be taken as more than a pun, Fat Moe asks, “Noodles, what you been doin’ all these years?” “Going to bed early” is the reply.

Finally, the coda transcends the temporal relations of the film’s events (the mise-en-scène of 1933): the last image is a kind of forever Noodles. In that last close-up a fine netting is placed between the character and the camera’s point-of-view: It is a veil — the garment of the dead wrapped around a corpse — and with the use of the freeze-frame, the image produces an almost shroud-like effect, the impression left on cloth of a dead figure’s features, Finally, for Noodles, there is oblivion; the smile is the last sign of the withdrawal from life and its memories, Metaphorically, it is the arrival of a sweet death, the kind of death Raymond Chandler once called “the big sleep”.

Deborah’s words to Noodles; “You can’t live in the past … or the future,” But, between the past and future, is the opium den. The past can never fully be exorcised; one must understand it and, in understanding it, find a kind of peace within its memories.

For all its faults — and the film has many — the last scene totally redeems it.

Notes:

1. The Age, 8 October 1984.

2. The Australian Financial Review, 12 October 1984.

3. Rolling Stone, No. 380, October 1984.

4. Neil Jillett. The Age. op.cit.

5. Meagban Morris, The Australian Financial Review, op.cit.

6. ibid.

7. Film Illustrated, Vol. 11, No. 124, January 1982.

Cinema Papers, December 1984; pp. 458-459