Cultural Trauma and “The Will to Myth”

by Gaylyn Studlar and David Desser

“History is what hurts,” writes Fredric Jameson in The Political Unconscious, “It is what refuses desire and sets inexorable limits to individual as well as collective praxis.” (102) The pain of history, its delimiting effect on action, is often seen as a political, a cultural, a national liability. Therefore, contemporary history has been the subject of an ideological battle which seeks to rewrite, to rehabilitate, controversial and ambiguous events through the use of symbols. One arena of on-going cultural concern in the United States is our involvement in Vietnam. It seems clear that reconstituting an image —a “memory”—of Vietnam under the impetus of Reaganism appears to fulfill a specific ideological mission. Yet the complexity of this reconstitution or rewriting has not been fully realized, either in film studies or in political discourse. Neither has the manner in which the Reaganite right coopted often contradictory and competing discourses surrounding the rehabilitation of Vietnam been adequately addressed. A string of “rightwing” Vietnam films has been much discussed, but their reliance on the specific mechanism of displacement to achieve a symbolic or mythic reworking of the war has not been recognized. Also insufficiently acknowledged is the fact that, far from being a unique occurrence, the current attempt to rewrite Vietnam, and the era of the 1960s more broadly, follows a well-established pattern of reworking the past in postwar Japan and Germany. Although it would be naive to advance a simple parallelist conception of history that foregrounds obvious analogies at the expense of important historical differences, the rewriting of the Vietnam war evidences a real, if complicated, link to previous situations where nations have moved beyond revising history to rewriting it through specific cultural processes.

That America’s “rewriting” of the Vietnam war is ideological in nature, of a particular political postwar moment, is clear a priori. But the site at which it is occurring is perhaps less clear and therefore more significant. For what is being rewritten might justifiably be called a “trauma,” a shock to the cultural system. Commonly used phrases such as “healing the wounds of Vietnam” are quite revelatory of this idea, but do not grasp the difficulty of any cultural recuperation from shock. In reality, the attempt to cope with the national trauma of Vietnam confronts less a physical than a psychic trauma. The mechanisms through which healing can occur, therefore, are more devious, more in need, if you will, of “analysis.”

The central question in the problem of the Vietnam war in history is: How can the US deal with not only its defeat in Vietnam, but with the fact that it never should have been there in the first place? By answering this question, the United States would confront the potentially painful revelations of its involvement in Vietnam, which is reminiscent of those questions faced by other nations: How can Japan cope with its role in the Pacific aggression of WWII? How can the West Germans resolve the Nazi era? These questions are virtually unanswerable without admission of guilt. But if, as Freud maintained, individuals find guilt intolerable and attempt to repress it, why should cultures be any different? (“Repression” 112) And if guilt, in spite of repression, always finds an unconscious avenue of expression in the individual’s life, we must similarly mark a return of the repressed in cultural discourse as well.

In one respect, the return of the repressed explains the number of Vietnam films appearing simultaneously, or at least in waves of films during the 1980s. Given the nature of film production, the box-office success of any individual film cannot account for so many Vietnam films appearing within a short period of time. Nor can the popularity of such films, left and right, automatically be taken as an indicator of psychic healing. On the contrary, their coexistence might be read as a register of the nation’s ambivalent feelings over the war, and ambivalence, Freud tells us, is one of the necessary ingredients in the creation of guilt feelings. (“Repression” 114-5)

Psychoanalytic therapy maintains that to be healed, one must recall the memory of the trauma which has been repressed by a sense of guilt. Otherwise, a “faulty” memory or outright amnesia covers the truth, which lies somewhere deep in the unconscious. The more recent the trauma, the more quickly the memory can be recalled; the more severe the original trauma, the more deeply the memory is buried, the more completely it is repressed. In this respect, cultures can be said to act like individuals—they simply cannot live with overwhelming guilt. Like individual trauma, cultural trauma must be “forgotten,” but the guilt of such traumas continues to grow. However, as Freud notes, the mechanism of repression is inevitably flawed: the obstinately repressed material ultimately breaks through and manifests itself in unwelcome symptoms. (112-3) In 1959 Theodor Adorno, calling upon the psychoanalytic explanation of psychic trauma in his discussion of postwar Germany, observed that the psychological damage of a repressed collective past often emerges through dangerous political gestures: defensive overreaction to situations that do not really constitute attacks, “lack of affect” in response to serious issues, and repression of “what was known or half-known.” (Adorno 116) Popular discourse often equates forgetting the past with mastering it, says Adorno, but an unmastered past cannot remain safely buried: the mechanisms of repression will bring it into the present in a form which may very well lead to “the politics of catastrophe.” (ibid. 128)

One example of the politics of catastrophe was Germany’s own unmastered response to World War I. Although Hitler’s rise to power was complex (as is America’s rewriting of the Vietnam War), there was a crucial element of psychic trauma that enabled Hitler to step in and “heal” the nation. In The Weimar Chronicle, Alex de Jonge offers a telling account of an element of this trauma. At the end of the war, the Germans were unable to comprehend that their army, which proudly marched through the Brandenburg gate, had been defeated. Instead of blaming the enemy, or the imperial regime’s failed policy of militarism, the Germans embraced the myth of the “stab in the back.” Defeat was explained as a conspiracy concocted by those Germans who signed the surrender. (32) William Shirer has noted that the widespread “fanatical” belief in this postwar myth was maintained even though “the facts which exposed its deceit lay all around.” (55-6) This act of “scapegoating” evidences both the desire to rewrite history and to repress collective cultural guilt and responsibility. Resistance to the truth meant that, for Nazi Germany, ideology functioned as “memory,” fantasy substituted for historical discourse, and the welcome simplicity of myth replaced the ambiguity of past experience. While WWI should have logically signalled an end to German militarist impulses, it served as merely a prelude to a “founding myth” for its most virulent expression. (de Jonge 32)

This example, replayed in many more contemporary realms, including the current discourse surrounding Vietnam, allows us to posit a “will to myth”—a communal need, a cultural drive—for a reconstruction of the national past in light of the present, a present which is, by definition of necessity, better. Claude Levi-Strauss has suggested that primitive cultures which have no past (i.e., do not conceive of or distinguish between a past and present) use myth as the primary means of dealing with cultural contradictions. Modern societies, of course, are cognizant of a past, but frequently find it filled with unpleasant truths and halfknown facts, so they set about rewriting it. The mass media, including cinema and television, have proven to be important mechanisms whereby this rewriting—this re-imaging—of the past can occur. Indeed, it was Hitler’s far-reaching use of the media that allowed him to solidify the National Socialist state and set his nation on its monstrous course in a carefully orchestrated exploitation of the will to myth. (Herzstein)

A common strategy by which “the will to myth” asserts itself is through the substitution of one question for another. This mechanism is invoked by Levi-Strauss as he notes how frequently one question, or problem, mythically substitutes for another concept by the narrative patterns of the myths. In dream interpretation, psychoanalysis calls this strategy “displacement.” If we allow the notion that cultures are like individuals (and recall the commonplace analogy that films are “like” dreams), we should not be surprised to find displacement occurring in popular discourse. Displacement accounts for the phenomenon of “scapegoating,” for instance, on both individual and cultural levels. But there are more devious examples, more complex situations in which the displacement goes almost unrecognized, as has been the case thus far with the current wave of Vietnam films and the project of rewriting the image of the war.

In the case of the recent rightwing Vietnam war films, the fundamental textual mechanism of displacement that has not been recognized is that the question “Were we right to fight in Vietnam?” has been replaced (displaced) by the question “What is our obligation to the veterans of the war?” Responsibility to and validation of the veterans is not the same as validating our participation in the conflict in the first place. Yet answering the second question “mythically” rewrites the answer to the first.

One of the key strategies in this displacement of the crucial question of America’s Vietnam involvement is that of “victimization.” The Japanese have used this method of coping with their role as aggressor in World War II, just as the Nazis used it to rewrite WWI. The Japanese soldiers who fought in the war now are regarded as victims of a military government that betrayed the soldiers and the populace. The Japanese do not try to justify their actions in the war nor even deal with the fact that their policies started the war in the first place. Rather, they try to shift (displace) blame for the war onto wartime leaders who are no longer alive. Contemporary Germany, too, relies on this strategy in an attempt now to rehabilitate West Germany’s Nazi past. Strangely enough, its appropriation was given public sanction by President Reagan in his visit to Bitburg cemetery.

That America’s problem of/with the Vietnam War might be related to Germany’s Nazi past and the controversy over Reagan’s visit to Bitburg is addressed in an interesting, if disturbing way, in a letter quoted by Alvin Rosenfeld. The letter writer claimed that Reagan’s trip to Bitburg signified “that we are beginning to forgive the German people for their past sins, in much the same way that American has begun to seek forgiveness for Vietnam.” (96) But is America (or, for that matter, West Germany) actually seeking “forgiveness” for the past? Reagan told the Germans at Bigburg what they wanted to hear, that the German soldiers buried in the military cemetery were themselves victims of the Nazis “just as surely as the victims of the concentration camps.” (ibid 94) The American resistance to admitting culpability for Vietnam, like the Bitburg affair, revolves around a collective cultural drama of memory and forgetting. In essence, what we find in Japan’s revision of its wartime history, Reagan’s Bitburg speech, and many of the Vietnam films of the 1980s, is that the appeal to victimization via “the will to myth” is a powerful rhetorical tool to apply to the problem of guilt. To be a victim means never having to say you’re sorry.

MIAs; or I am a Fugitive from Bureaucracy

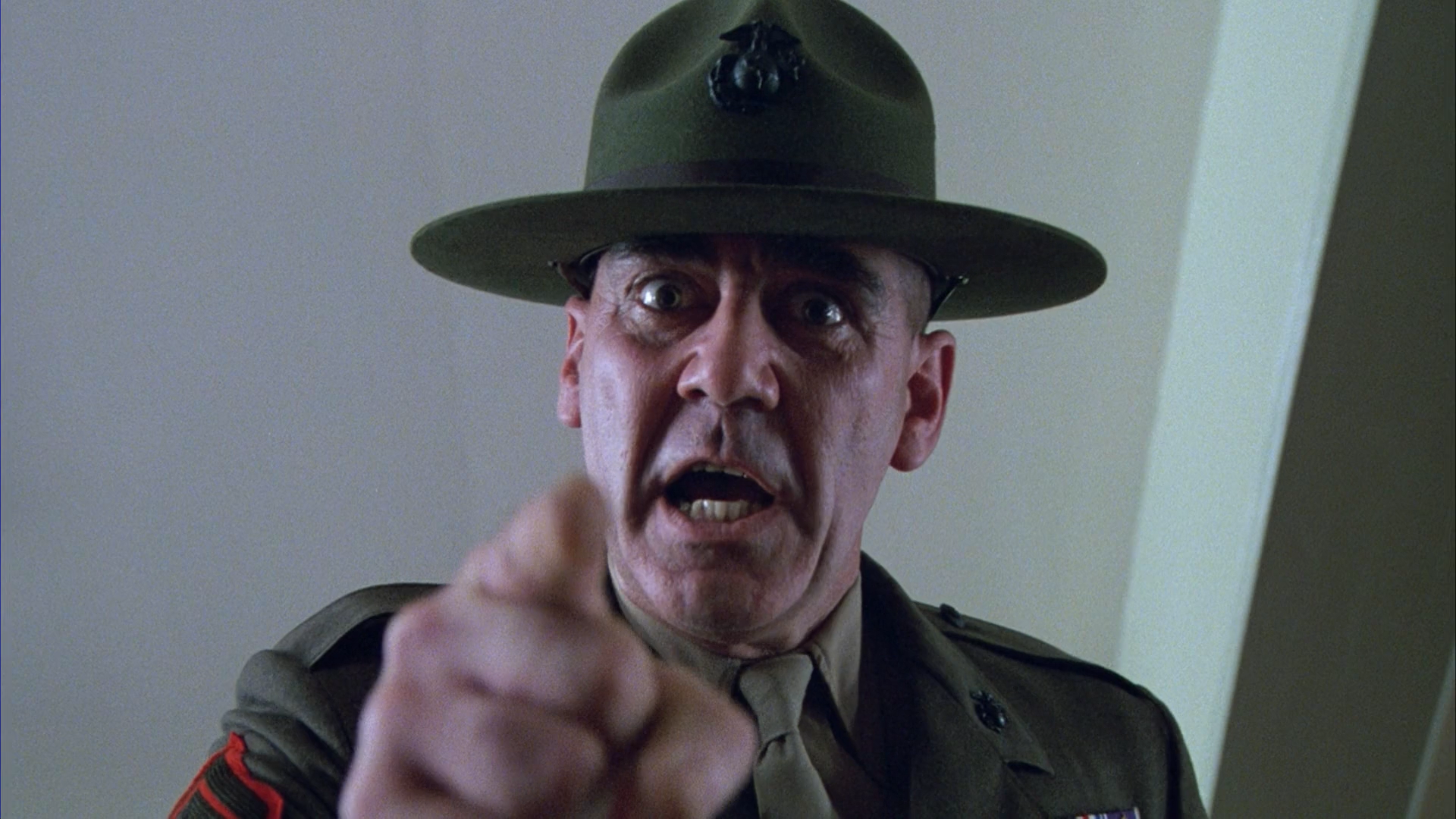

As of this writing, two waves of Vietnam war films in the 1980s have been claimed: the rightwing revisionism of Uncommon Valor (1983), Missing in Action (1984), and Rambo: First Blood II (1985); and the ostensibly more realistic strain of Vietnam films emerging with Platoon (1986), Hamburger Hill (1987), and Full Metal Jacket (1987). At first glance, the comic-book heroics of the earlier films seem antithetical to the “realism” of the later ones, but in spite of such differences the films are actually very much alike in their dependence on the strategy of victimization. The films all work to evoke sympathy for the American GI (today’s veteran) and pay tribute to the act of remembering the war as private hell. While the right wing films, especially Rambo, justify a private war of national retribution for the personal sacrifice of vets, the realist films demonstrate the process of victimization of the draftee or enlisted man. Platoon even goes so far as to transpose its conflict from the specificity of Vietnam into the realm of the transcendental: the two sergeants, Barnes and Elias, become mythic figures, warrior archetypes, battling for the soul of Chris (Christ?). The crucifixion image as Barnes kills Elias is too clear to miss, while Chris becomes the sacrificial victim who survives.

The right wing films, especially Rambo, most clearly demonstrate the strategy of mythic substitution or displacement in the use of an oft-repeated rumor: that American MIAs are still being held captive in southeast Asia. That Rambo was not only the most commercially successful of all the Vietnam films thus far, but also became culturally ubiquitous (a television cartoon series, formidable tie-in merchandise sales, and, like Star Wars, becoming part of political discourse) speaks to the power of the will to myth. The need to believe in the MIAs gives credence to the view that the Vietnamese are now and therefore have always been an inhuman and cruel enemy. Vietnam’s alleged actions in presently holding American prisoners serves as an index of our essential rightness in fighting such an enemy in the past. Moreover, our alleged unwillingness to confront Vietnam on the MIAs issue is taken to be an index of the government’s cowardice in its Vietnam policy: Confrontation would mean confirmation. The American bureaucracy remains spineless: They didn’t let us win then, and they won’t let us win again.

Consequently, while it appears to embrace the militaristic ideology of the radical right, Rambo simultaneously delegitimizes governmental authority and questions the ideological norms of many other Vietnam films. Within its formula of militaristic zeal, Rambo sustains an atmosphere of post-Watergate distrust of government. The MIAs, John Rambo’s captive comrades, are regarded only as “a couple of ghosts” by the cynical official representative of the government, Murdock, who lies about his service in Vietnam. He is willing to sacrifice the MIAs to maintain the status quo of international relations. President Reagan’s portrait graces the wall behind Murdock’s desk, but Murdock is a “committee” member, aligned, it seems, with Congress, not with the avowed conservatism of the executive branch. Colonel Trauptman, Rambo’s Special Forces commander and surrogate father-figure, reminds Murdock that the United States reneged on reparations to the Vietnamese, who retaliated by keeping the unransomed captive Americans. Failure to rescue the MIAs is the direct result of their economic expendability. Murdock says the situation has not changed; Congress will not appropriate billions to rescue these “ghosts.”

Abandoned once by their country (or rather, “government”), the POWs/MIAs are abandoned yet again in a highly symbolic scene: airdropped into Vietnam to find and photograph any living MIAs/POWs, Rambo locates an American; the rescue helicopter hovers above them as Vietnamese soldiers close in. Murdock abruptly aborts the mission. Rambo is captured and submitted to shocking (literally) tortures. His Russian interrogators taunt him with the intercepted radio message in which he was ordered abandoned. Rambo escapes, but not before he swears revenge against Murdock.

The mythical MIA prisoners may represent the ultimate American victims of the war, but Rambo: First Blood II also draws on the victimization strategy on yet another level, through the continued exploitation of its vet hero, John Rambo. The film opens with an explosion of rock at a quarry. A tilt down reveals inmates at forced labor. Colonel Trauptman arrives to recruit Rambo for a special mission. Separated by an imposing prison yard fence, Rambo tells Trauptman that he would rather stay in prison than be released because “at least in here I know where I stand.” The Vietnam vet is the eighties version of the World War I vet, the “forgotten man” of the Depression era. Like James Allen in Warner Brothers most famous social consciousness film, I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932), Rambo is a Congressional Medal of Honor winner who feels “out of step” with a society that has used and discarded him. Condemned as a common criminal, Rambo is released from military prison and promised a pardon because his unique combat skills are again required by the government. He does not realize that he is also needed for political purposes. He will provide the gloss of a veteran’s testimonial to the mission’s findings, which have been predetermined: no Americans will be found.

As far removed from an appeal to victimization as Rambo’s aggressive received myth-image might appear to be, his personal mission of victory and vengeance crucially hinges on his status as present and past victim, as neglected, misunderstood, and exploited veteran. Ironically, in a film that has no memory of the historical complexities of the Vietnam war, Rambo’s personal obsession with the traumatic past of Vietnam is cited as the truest measure of his unswerving patriotism. Even Colonel Trauptman feels compelled to tell him to forget the war. Rambo replies: “. . . as long as I’m alive—it’s still alive.”

Stallone explained the film in an interview: “I stand for ordinary Americans, losers a lot of them. They don’t understand big, international politics. Their country tells them to fight in Vietnam? They fight.” (Grenier) Rambo and the captive MIAs are the innocent victims of wartime and postwar government machinations that preclude victories. By implicating American policy and government bureaucracy in past defeat and current inaction, the film exonerates the regular soldier from culpability in American defeat as it pointedly criticizes a technologically obsessed, mercenary American military establishment. This echoes both the Japanese strategy of blaming dead leaders for WWII and Reagan’s declaration at Bitburg that the Holocaust was not the responsibility of a nation or an electorate, but an “awful evil started by one man.” (Reagan 131) Similarly, in his statements on Vietnam, Reagan has employed a strategy of blaming Vietnam defeat on those who cannot be named: “We are just beginning to realize how we were led astray when it came to Vietnam.” (Clines)

“Are they going to let us win this time?” Rambo first asks Trauptman when the colonel comes to pull Rambo out of the stockade rock pile for sins committed in the presequel. Trauptman says that it is up to Rambo, but the colonel is unaware that Murdock is merely using Rambo to prove to the American public that there are no POWs. As the film’s ad proclaims: “They sent him on a mission and set him up to fail.” Rambo, setting the ideological precedent for Ollie North, is the fall guy forced into extraordinary “moral” action by the ordinary immoral inaction of bureaucrats. According to official standards, Rambo is an aberration, the loose cannon on the deck who subverts the official system, but in doing so he affirms the long-cherished American cult of the individual who goes outside the law to get the job done. He ignores the “artificial” restraints of the law to uphold a higher moral law, but (unlike Ollie) Rambo manages to avoid the final irony of conspiracy-making.

Confronting the Otherness of Frontier Asia

In rewriting the Vietnam defeat, Rambo attempts to solve the contradiction posed by its portrayal of the Vietnam vet as powerless victim and suprematist warrior by reviving the powerful American mythos of a “regeneration through violence.” Identified by Richard Slotkin as the basis of many frontier tales, this intertext illuminates the way in which Rambo’s narrative structure resembles that of the archetypal captivity narrative described by Timothy Flint, whose Indian Wars of the West, Biographical Memoir of Daniel Boone (1828-33) typified this form of early frontier story. In this formula, a lone frontier adventurer is ambushed and held captive by Indians. They recognize his superior abilities and wish to adopt him, but he escapes, reaches an outpost, and with the help of a handful of other settlers wins a gruesome siege against hundreds of his former captors (Slotkin 421). Sanctified by the trial of captivity, the hunter confronts an Otherness, represented by the wilderness and the Indians, that threatens to assimilate him into barbarism. Through vengeance, he finds his identity—as white, civilized, Christian male.

Rambo’s war of selective extermination inverts the wartime situation of Vietnam into a hallucinated frontier revenge fantasy that liter-alizes Marx’s description of ideology: “circumstances appear upside down . . (37-8). Rambo is an imperialist guerrilla, an agent of technocrats, who rejects computer-age technology to obliterate truckloads of the enemy with bow and arrow. Emerging from the mud of the jungle, from the trees, rivers, and waterfalls, Rambo displays a privileged, magical relationship to the Third World wilderness not evidenced even by the Vietnamese. As Trauptman remarks: “What others call hell, he calls home.”

Charmed against nature and enemy weapons, Rambo retaliates in Indian-style warfare for the captivity of the POWs, the death of his Vietnamese love interest, and his own wartime trauma. He stands against a waterfall, magically immune to a barrage of gunfire. His detonator-tipped arrows literally blow apart the enemy— who is subhuman, the propagandist’s variation on the Hun, the Nip, the Nazi. Held in contempt even by their Russian advisors, the Vietnamese are weak, sweating, repulsive in their gratuitous cruelty and sexual lasciviousness. Rambo annihilates an enemy whose evil makes American culpability in any wartime atrocities a moot point. In The Searchers, Ethan Edwards says: “There are humans and then there are comanch.” In Rambo, there are humans and then there are gooks who populate a jungle which is not a wildnerness to be transformed into a garden, but an unredeemable hell which automatically refutes any accusation of America’s imperialist designs.

With regard to the captivity narrative, it is also significant that Rambo is described as a half-breed, half German and half American Indian, a “hell of a combination,’’ says Murdock. The Vietnam’s vet’s otherness of class and race is displaced solely onto race. The In-dianness of costume signifiers: long hair, bare chest, headband, and necklace/pendant ironically reverse the appropriation of the iconography of Native Americans by the sixties counterculture as symbolic of a radical alternative to oppressive cultural norms (Slotkin 558). Ironically, the film’s appropriation of the iconography of the noble savage also permits Rambo to symbolically evoke the Indian as the romanticized victim of past government deceitfulness disguised as progress (i.e., genocide). These invocations of Indianness should not overshadow the fact that Rambo is a white male, as are most of the men he rescues. Thus the film elides the other question of color—the fact that “half the average combat rifle company . . . consisted of blacks and Hispanics.’’ (Kolko 360) American racism, and the class bias of the culture found the US armed services in Vietnam consisting of a majority of poor whites and blacks, especially among the combat soldiers, the “grunts.” The captivity narrative overshadows the historical narrative of rebellion in the ranks of the grunts (fragging—the killing of officers) and the feeling of solidarity that soldiers of color felt for their Vietnamese opponents.

The reliance on the captivity narrative and Indian iconography evidences a desperate impulse to disarticulate a sign—the Vietnam veteran—from one meaning (psychopathic misfit, murderer of women and children to another, the noble savage. Stallone admitted in an interview that the rushes of the film made Rambo look “nihilistic almost psychopathic” (Grenier). The film cannot repress an ambivalence toward the Vietnam veteran, in spite of the noble-savage iconography. By emphasizing the efficiency of Rambo as a “killing machine” created by Trauptman, Stallone’s protagonist becomes an American version of Frankenstein’s monster. He begins to evoke figures from genre films such as the Terminator, or Jason in Friday the 13th, in his sheer implacability and indestructibility. One critic has written that Michael, the hero of The Deer Hunter, confronts the perversity of Vietnam’s violence “with grace.” (Kinney 40) Rambo, as the embodiment of the return of the repressed, can only confront perversity with perversity.

Through the castrated/castrating dialectic of sacrifice and sadistic violence, Rambo redeems the MIAs and American manhood, but in spite of his triumph of revenge, he has not been freed of his victim status at the end of the film. Trauptman tells him: “Don’t hate your country .. .” Rambo’s impassioned final plea states that all he wants is for his country to love the vets as much as they have loved their country. Trauptman asks, “How will you live, John?” Rambo replies, “Day by day.” The ending suggests that the screenwriters absorbed much from Warner Brothers’ I am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang in which veteran Allen, duped by bureaucrats, is returned to prison and denied his promised pardon. He escapes a second time to tell his fiancee, “I hate everything but you …” She asks, “How do you live?” Allen: “I steal.” While Allen disappears into darkness, Rambo’s walk into the Thai sunset also serves to recall the ending of numerous Westerns in which the hero’s ambivalence toward civilization and the community’s ambivalence toward the hero’s violence precludes their reconciliation. Like Ethan Edwards, Rambo is doomed to wander between the two winds, but to a 1980s audience, no doubt, the ending does not signal the awareness of the tragic consequences of unreasoning violence and racial hatred as in Ford’s film, but the exhilarating possibility of yet another Stallone sequel.

Luxuriating in Their Patriotic Symptoms

Like populist discourses such as Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA,” Rambo plays upon a profound ambivalence toward the Vietnam vet, the war, and the US government but, like Springsteen’s song, Rambo has been incorporated into the popular discourse as a celebration of Americanism. In its obvious preferred reading, the film is decoded by its predominantly post-Vietnam, male audience as a unified, noncontradictory system. (Ellis) This kind of integration into the cultural discourse is possible because the will to myth overrides the ideological tensions that threaten the coherence of the film’s textual system. The film does not require a belief in history, only a belief in the history, conventions, and mythmaking capacity of the movies.

In a challenging essay in Postmodernism and Politics, Dana Polan speaks of cinema’s “will-to-spectacle,” the banishment of background, the assertion that “a world of foreground is the only world that matters or is the only world that is.” (60—emphasis in original) If one eliminates the past as background, events can be transformed into satisfying spectacle, hurtful history into pleasurable myth. Drawing on this will-to-spectacle, the mythogenesis of Rambo lies, not in history, but in the «r-texts of fiction that provide its mythic resonance as a genre film and its vocabulary for exercising the will to myth.

In fact, virtually all background is eliminated in Rambo, and the spectacle becomes the half-clad, muscle-bound body of Sylvester Stallone: the inflated body of the male as the castrated and castrating monster. John Rambo is the body politic offered up as the anatomically incorrect action doll—John Ellis describes an ad for the film showing Rambo holding “his machine gun where his penis ought to be.’’ (15) Rambo declares that “the mind is the best weapon,” but Stallone’s glistening hypermasculinity, emphasized in the kind of languid camera movements and fetishizing close-up usually reserved for female “flashdancers,” visually insists otherwise.

Rambo‘s narcissistic cult of the fetishized male body redresses a perceived loss of personal and political power at a most primitive level, at the site of the body, which often defined the division of labor between male and female in pretechnological, patriarchal societies. The male body as weapon functions as a bulwark against feelings of powerlessness engendered by technology, minority rights, feminism—this helps explain the film’s popularity not only in the US but overseas as well, where it similarly appealed to working-class, male audiences. (Ellis) Most of all, however, the film speaks to post-Vietnam/post-Watergate America’s devastating loss of confidence in its status as the world’s most powerful, most respected, most moral nation. Our judgment and ability to fight the “good” war as a total war of commitment without guilt has been eroded by our involvement in Vietnam, as surely as a sense of personal power has been eroded by a society increasingly bewildering in its technological complexity.

Attempting to deliver its audience from the anxiety of the present, Rambo would seek to restore an unreflective lost Eden of primitive masculine power. Yet Rambo must supplement his physical prowess with high-tech weapons adapted to the use of the lone warrior-hero. A contradictory distinction is maintained between his more “primitive” use of technology and that of the bureaucracy. Rambo’s most hysterical, uncontrollable act of revenge is against Murdock and Murdock’s technology. He machine-guns the computers and sophisticated equipment in operations headquarters. Uttering a primal scream, he then turns his weapon to the ceiling in a last outburst of uncontrollable rage. Such an outburst is the predictable result of the dynamics of repression, for the film cannot reconstitute institutional norms except through the mythological presence of the super-fetishized superman, who functions as the mediator between the threatened patriarchal ideology and the viewer/subject desperately seeking to identity with a powerful figure. As a reaction formation against feelings of powerlessness too painful to be admitted or articulated, Rambo’s violent reprisals, dependent on the power of the over-fetishized male body, may be read as a symptomatic expression, a psychosomatic signifier of the return of the repressed, suggesting profound ideological crisis in the patriarchy.

Freud warned that within the context of repression and unconscious acting out, the young and childish tend to “luxuriate in their symptoms.” (12:152) Rambo demonstrates a cultural parallel, a luxuriating in the symptoms of a desperate ideological repression manifested in the inability to speak of or remember the painful past, a cultural hysteria in which violence must substitute for understanding, victimization for responsiblity, the personal for the political. While Rambo reflects ambiguous and often inchoate drives to rewrite the Vietnam war, it also shows how in the will to myth the original traumatic experience is compulsively acted out in a contradictory form that leaves the origins of ideological anxiety untouched: the need to reconcile repressed material remains.

WORKS CITED

Adorno, Theodor W. “What Does Coming to Terms with the Past Mean?” Bitburg in Moral and Political Perspective, Ed. Geoffrey H. Hartman. Bloomington, IN: Indiana UP, 1986. 114-29.

Clines, Francis X. “Tribute to Vietnam Dead: Words, A Wall.” New York Times 11 Nov., 1982: B15.

Ellis, John. “ ‘Rambollocks’ is the Order of the Day,” New Statesman 8, Nov. 1985: 15.

Freud, Sigmund. “Remembering, Repeating, and Working-Through.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works, Ed. and Trans. James Strachey. 23 vols. London: Hogarth P., 1953-66. 12: 147-56.

——-“Repression.” General Psychological Theory. Ed. Philip Rieff. New York: Macmillan-Collier, 1963. 104-15.

Grenier, Richard. “Stallone on Patriotism and ‘Rambo.’ ” New York Times 6 June, 1985: C21.

Herzstein, Robert Edwin. The War that Hitler Won: The Most Infamous Propaganda Campaign in History. New York: Putnam’s, 1978.

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1981.

Jonge, Alex de. The Weimar Chronicle. London: Paddington P, 1978.

Kinney, Judy S. “The Mythical Method: Fictionalizing the Vietnam War.” Wide Angle 7, 4 (1985): 35-40.

Kolko, Gabriel. Anatomy of a War: Vietnam, the United States, and the Modern Historical Experience. New York: Pantheon, 1985.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. Vol. 1. Trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. New York: Basic Books, 1963.

Marx, Karl, and Frederick Engels. The German Ideology. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1965.

Polan, Dana. “ ‘Above All Else to Make You See’: Cinema and the Ideology of Spectacle.” Postmodernism and Politics. Ed. Jonathan Arac. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1986. 55-69.

Reagan, Ronald. “Never Again . . .” in Bitburg and Beyond. Ed. Ilya Levkov. New York: Shapolsky, 1987. 131-34.

Rosenfeld, Alvin H. “Another Revisionism: Popular Culture and the Changing Image of the Holocaust.” Hartman 90-102.

Shirer, William. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett, 1960.

Slotkin, Richard. Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600-1860. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP, 1973.

Film Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 1. (Autumn, 1988), pp. 9-16.

Also published in From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film, edited by Linda Dittmar, Gene Michaud