Master filmmaker Raoul Peck envisions the book James Baldwin never finished, Remember This House. The result is a radical, up-to-the-minute examination of race in America, using Baldwin’s original words and flood of rich archival material. I Am Not Your Negro is a journey into black history that connects the past of the Civil Rights movement to the present of #BlackLivesMatter. It is a film that questions black representation in Hollywood and beyond. And, ultimately, by confronting the deeper connections between the lives and assassination of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., Baldwin and Peck have produced a work that challenges the very definition of what America stands for.

* * *

In June 1979, acclaimed author James Baldwin commits to a complex endeavor: tell the story of America through the lives of three of his murdered friends: Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr, Malcolm X. Baldwin never got past his 30 pages of notes entitled: Remember this House.

[The Dick Cavett Show – 1968]

Dick Cavett: Mr. Baldwin, I’m sure you still meet the remark that: “What are the Negroes… why aren’t they optimistic? Um… They say, “But it’s getting so much better. There are negro mayors, there are negroes in all of sports.” There are negroes in politics. They’re even accorded the ultimate accolade of being in television commercials now.

(audience laugh)

I’m glad you’re smiling.

(audience laugh)

Is it at once getting much better and still hopeless?

James Baldwin: I don’t think there’s much hope for it, you know, to tell you the truth, as long as people are using this peculiar language. It’s not a question of what happens to the Negro here, or to the black man here, that’s a very vivid question for me, you know, but the real question is what’s going to happen to this country. I have to repeat that.

[Buddy Guy “Damn Right, I’ve Got The Blues” (1991) playing]

♪ You’re damn right, I’ve got the blues, ♪

♪ From my head down to my shoes ♪

♪ You’re damn right, I’ve got the blues, ♪

♪ From my head down to my shoes ♪

♪ I can’t win ♪

♪ ‘Cause I don’t have a thing to lose ♪

♪ I stopped by my daughter’s house ♪

♪ You know I just want to use the phone ♪

♪ I stopped by my daughter’s house ♪

♪ You know I just want to use the phone ♪

(James Baldwin narrating)

To Jay Acton

Startan Literary Agency

June 30th, 1979

My dear Jay,

I’ll confess to you that I am writing the enclosed proposal in a somewhat divided frame of mind.

(siren blaring)

The summer has scarcely begun, and I feel already that it’s almost over. And I will be 55. Yes, 55, in a month. I am about to undertake the journey. And this is a journey, to tell you the truth, which I always knew that I would have to make, but had hoped, perhaps, certainly had hoped, not to have to make so soon.

I am saying that a journey is called that because you cannot know what you will discover on the journey, what you will do with what you find, or what you find will do to you.

[THE MONTGOMERY BUS BOYCOTT, ALABAMA – 1955/1956]

Martin Luther King Jr: Not only have a right to be free, we have a duty to be free.

Crowd: Yeah.

Martin Luther King Jr: When you sit down on the bus and you sit down in the front, or sit down by a white person, you are sitting there because you have a duty to sit down, not merely because you have a right.

Baldwin: The time of these lives and deaths, from a public point of view, is 1955, when we first heard of Martin, to 1968, when he was murdered. Medgar was murdered in the summer of 1963. Malcolm was murdered in 1965.

♪ Here, take my hand, Precious Lord ♪

♪ Lead me on ♪

♪ Let me stand ♪

♪ I am tired ♪

♪ I’m weak ♪

♪ I am worn ♪

♪ Through the storm ♪

Baldwin: The three men, Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin, were very different men. Consider that Martin was only 26 in 1955. He took on his shoulders the weight of the crimes, and the lies, and the hope of a nation. I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other, as in truth, they did and use their dreadful journey as a means of instructing the people whom they loved so much, who betrayed them, and for whom they gave their lives.

(train rattles)

PAYING MY DUES

[LEANDER PEREZ, WHITE CITIZENS COUNCIL]

Leander Perez: The moment a negro child walks into the school, every decent, self-respecting, loving parent should take his white child out of that broken school.

(indistinct chatter)

[CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL, LITTLE ROCK, ARK – 1957]

Go back to your own school.

God forgives murder and he forgives adultery. But He is very angry and He actually curses all who do integrate.

(crowd shouting)

(whistles blowing)

Baldwin: That’s when I saw the photograph. On every newspaper kiosk on that wide, tree-shaped boulevard in Paris, were photographs of 15-year-old Dorothy Counts being reviled and spat upon by the mob as she was making her way to school in Charlotte, North Carolina. There was unutterable pride, tension and anguish in that girl’s face as she approached the halls of learning, with history jeering at her back. It made me furious, it filled me with both hatred and pity. And it made me ashamed. Some one of us should have been there with her! But it was on that bright afternoon that I knew I was leaving France. I could simply no longer sit around Paris, discussing the Algerian and the Black American problem. Everybody else was paying their dues, and it was time I went home and paid mine.

♪ If you was white, You’d be alright ♪

♪ If you was brown, Stick around ♪

♪ But as you’s black ♪

♪ Oh, brother ♪

♪ Get back, get back, get back ♪

♪ I went to an employment office ♪

♪ I got a number and I got in line ♪

♪ They called everybody’s number ♪

♪ But they never did call mine ♪

♪ I said, if you was white, You’d be alright ♪

♪ If you was brown, Stick around ♪

♪ But as you’s black ♪

♪ Oh, brother… ♪

(sirens blaring)

(indistinct speech)

Baldwin: I had at last come home. If there was, in this, some illusion, there was also much truth. In the years in Paris, I had never been homesick for anything American. Neither waffles, ice cream, hot dogs, baseball, majorettes, movies, nor the Empire State Building, nor Coney Island, nor the Statue of Liberty, nor the Daily News, nor Times Square. All of these things had passed out of me. They might never had existed, and it made absolutely no difference to me if I never saw them again.

But I missed my brothers and sisters, and my mother. They made a difference. I wanted to be able to see them, and to see their children. I hoped that they wouldn’t forget me. I missed Harlem Sunday mornings and fried chicken, and biscuits, I missed the music, I missed the style… that style possessed by no other people in the world. I missed the way the dark face closes, the way dark eyes watch, and the way, when a dark face opens, a light seems to go everywhere. I missed, in short, my connections, missed the life which had produced me and nourished me and paid for me. Now, though I was a stranger, I was home.

(music playing)

[DANCE, FOOLS, DANCE H. BEAUMONT – 1931]

Baldwin: I am fascinated by the movement on and off the screen. I am about seven. I’m with my mother, or my aunt. The movie is Dance, Fools, Dance.

I was aware that Joan Crawford was a white lady. Yet, I remember being sent to the store sometime later, and a colored woman who, to me, looked exactly like Joan Crawford, was buying something. She was incredibly beautiful. She looked down at me with so beautiful a smile that I was not even embarrassed, which was rare for me.

(applause)

HEROES

Baldwin: By this time, I had been taken in hand by a young white schoolteacher named Bill Miller, a beautiful woman, very important to me. She gave me books to read and talked to me about the books, and about the world: about Ethiopia, and Italy, and the German Third Reich, and took me to see plays and films, to which no one else would have dreamed of taking a ten-year-old boy.

(indistinct singing)

(shouting)

(drums playing)

[KING KONG, M.C. COOPER – 1933]

Baldwin: It is certainly because of Bill Miller, who arrived in my terrifying life so soon, that I never really managed to hate white people. Though, God knows, I’ve often wished to murder more than one or two.

(shouting and jeering)

Therefore, I begin to suspect that white people did not act as they did because they were white, but for some other reason.

(whimpering)

I was a child of course, and therefore unsophisticated. I took Bill Miller as she was, or as she appeared to be to me. She too, anyway, was treated like a n*gger, especially by the cops, and she had no love for landlords.

[RICHARD’S ANSWER, W. FOREST CRUNCH – 1945]

♪ Richard! Can’t get him up! ♪

♪ Richard! Can’t get him up! ♪

♪ Richard! Can’t get him up! ♪

♪ Lazy Richard! Can’t get him up! ♪

♪ Richard! ♪

Baldwin: In these days, no one resembling my father has yet made an appearance on the American cinema scene.

♪ Can’t get him up! ♪

♪ We’ll try to get him on the phone ♪

♪ I was laying down dreamin’… ♪

Baldwin: No, it’s not entirely true. There were, for example, Stepin Fetchit and Willie Best and Mantan Moreland, all of whom, rightly or wrongly, I loathed. It seemed to me that they lied about the world I knew, and debased it, and certainly I did not know anybody like them, as far as I could tell. For it also possible that their comic, bug-eyed terror contained the truth concerning a terror by which I hoped never to be engulfed.

[THE MONSTER WALKS, F.R. STRAYER – 1932]

Yet, I had no reservations at all concerning the terror of the Black janitor in They Won’t Forget.

[THEY WON’T FORGET, M. LEROY – 1937]

Give me police! Give me police! Give me… Give me police!

Baldwin: I think that it was a black actor named Clinton Rosemond who played this part, and he looked a little like my father.

I didn’t do it. I didn’t do it! I didn’t do it! I didn’t do it!

Baldwin: He is terrified because a young white girl in this small Southern town has been raped and murdered, and her body has been found upon the premises of which he is the janitor.

Good morning, Tump.

Baldwin: The role of the janitor is small, yet the man’s face bangs in my memory until today.

I have done nothing.

Nobody says you have, Tom. But they might.

Baldwin: The film’s icy brutality both scared me…

What for?

…and strengthened me.

[UNCLE’S TOM’S CABIN, H.A. POLLARD – 1927]

(whipping)

(inaudible)

(whipping)

“He’s done fo’ Massa.”

“Take him out!”

Baldwin: Because Uncle Tom refuses to take vengeance in his own hands, he was not a hero for me.

[STAGECOACH, J. FORD – 1939]

(gunshot)

(screaming)

Baldwin: Heroes, as far as I could see, where white, and not merely because of the movies, but because of the land in which I lived, of which movies were simply a reflection. I despised and feared those heroes because they did take vengeance into their own hands. They thought vengeance was theirs to take. And, yes, I understood that: my countrymen were my enemy.

(screaming)

Baldwin: I suspect that all these stories are designed to reassure us that no crime was committed. We’ve made a legend out of a massacre.

[CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY DEBATE – 1965]

Baldwin: Leaving aside all the physical facts which one can quote. Leaving aside rape or murder. Leaving aside the bloody catalog of oppression, which we are, in one way, too familiar with already, what this does to the subjugated is to destroy his sense of reality. This means, in the case of an American negro, born in that glittering republic, and in the moment you are born, since you don’t know any better, every stick and stone and every face is white, and since you have not yet seen a mirror, you suppose that you are too. It comes as a great shock around the age of five, or six, or seven, to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you.

(crowd murmur)

Baldwin: It comes as a great shock to discover the country, which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not, in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you.

To Jay Acton

Spartan Literary Agency

My dear Jay,

You must, it is to be hoped, be as curious as I am concerning the execution of this book project.

Baldwin: I know how to do it, technically. It is a matter of research and journeys. And with you or without you, I will do it anyway. I begin in September, when I go on the road. “The road” means my return to the South. It means briefly, for example, seeing Myrlie Evers, and the children. Those children who are children no longer. It means going back to Atlanta, to Selma, to Birmingham. It means seeing Coretta Scott King, and Martin’s children. I know that Martin’s daughter, whose name I don’t remember, and Malcolm’s oldest daughter, whose name is Attalah are both in the theatre, and apparently are friends. It means seeing Betty Shabazz, Malcolm’s widow, and the five younger children. It means exposing myself as one of the witnesses to the lives and deaths of their famous fathers. And it means much, much more than that. “A clod of witnesses,” as old St. Paul once put it.

WITNESS

I first met Malcolm X.

Baldwin: I saw Malcolm before I met him. I was giving a lecture somewhere in New York. Malcolm was sitting in the first row of the hall, bending forward at such an angle that his long arms nearly caressed the ankles of his long legs, staring up at me. I very nearly panicked. I knew Malcolm only by legend, and this legend, since I was a Harlem street boy, I was sufficiently astute to distrust. Malcolm might be the torch that white people claim he was, though, in general, white America’s evaluations of these matters would be laughable and even pathetic did not these evaluations have such wicked results. On the other hand, Malcolm had no reason to trust me either. And so I stumbled through my lecture, with Malcolm never taking his eyes from my face.

♪ Don’t know why ♪

♪ There’s no sun up in the sky ♪

♪ Stormy weather ♪

♪ Since my man and I ain’t together ♪

♪ Keeps rainin’ all the time ♪

Baldwin: As a member of the NAACP, Medgar was investigating the murder of a black man, which had occurred months before, had shown me letters from black people asking him to do this, and he had asked me to come with him.

♪ Raise up! ♪

♪ Get yourself together, And drive that funky soul ♪

Baldwin: I was terribly frightened, but perhaps that fieldtrip will help us define what I mean by the word “witness”. I was to discover that the line which separates a witness from an actor is a very thin line indeed. Nevertheless, the line is real. I was not, for example, a Black Muslim, in the same way, though for different reasons, that I never became a Black Panther. Because I did not believe that all white people were devils, and I did not want young black people to believe that. I was not a member of any Christian congregation because I knew that they had not heard and did not live by the commandment, “Love one another as I love you.” And I was not a member of the NAACP because in the North, where I grew up, the NAACP was fatally entangled with black class distinctions, or illusions of the same, which repelled a shoe-shine boy like me.

I did not have to deal with the criminal state of Mississippi, hour by hour and day by day, to say nothing of night after night. I did not have to sweat cold sweat after decisions involving hundreds of thousands of lives. I was not responsible for raising money, or deciding how to use it. I was not responsible for strategy controlling prayer-meetings, marches, petitions, voting registration drives. I saw the Sheriffs, the Deputies, the Storm Troopers, more or less in passing. I was never in town to stay. This was sometimes hard on my morale, but I had to accept, as time wore on, that part of my responsibility, as a witness, was to move as largely and as freely as possible. To write the story, and to get it out.

March, 1966

FBI MEMORANDUM

INFORMATION CONCERNING JAMES ARTHUR BALDWIN

To assistant FBI director Alan Rosen

Bereau files reveal that Baldwin, a negro author, was born in NYC and has lived and travelled in Europe.

He has become rather well-known due to his writing dealing with the relationship of white and negroes.

It has been heard that Baldwin may be an homosexual and he appeared as if he may be one.

J. Edgar Hoover, Head of the FBI: We should all be concerned with but one goal, the eradication of crime. The Federal Bureau of Investigation is as close to you as your nearest telephone. It seeks to be your protector in all matters within its jurisdiction. It belongs to you.

Information collected clearly depicted the subject as a dangerous individual who could be expected to commit acts inimical to the national defense and public safety to the United States in times of emergency.

Consequently his name is being included in the security index.

(rocket firing)

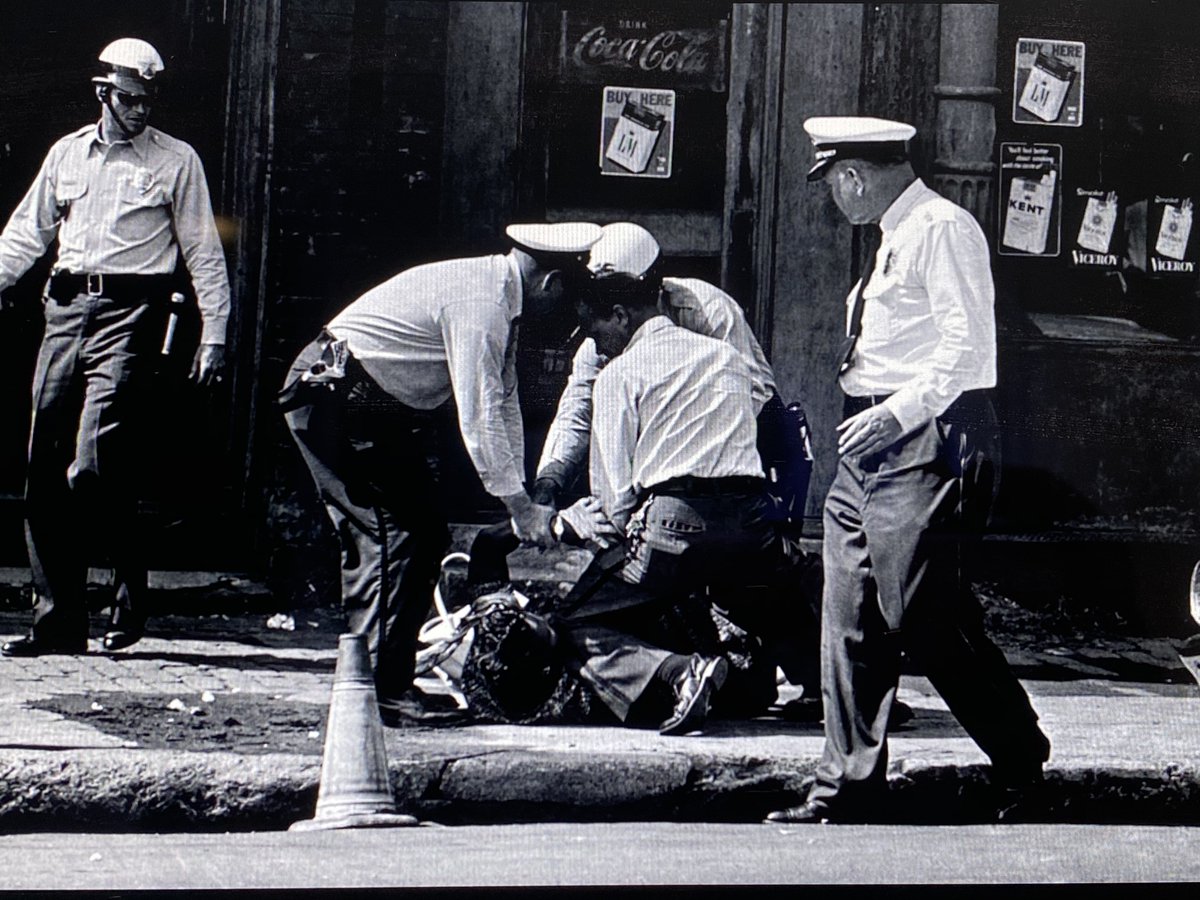

Baldwin: White people are astounded by Birmingham. Black people aren’t. White people are endlessly demanding to be reassured that Birmingham is really on Mars. They don’t want to believe, still less to act on the belief, that what is happening in Birmingham is happening all over the country.

(chanting)

(whistle blowing)

Baldwin: They don’t want to realize that there is not one step, morally or actually, between Birmingham and Los Angeles.

(crowd shouting)

[THE BIRMINGHAM CAMPAIGN, ALA. – 1963]

(singing and clapping)

Officer: Move on, move on!

(singing continues)

[DR KENNETH CLARK, THE NEGRO AND THE AMERICAN PROMISE – 1963]

Dr Kenneth Clark: We’ve invited three men, on the forefront of The Negro Struggle, to sit down and talk with us in front of the television camera. Each of these men, through his actions and his words, but with vastly different manner and means, is a spokesman for some segment of the Negro people today.

Malcolm X: Black people in this country have been the victims of violence at the hands of the white man for 400 years. And following the ignorant negro preachers, we have thought that it was Godlike to turn the other cheek to the brute that was brutalizing us.

Dr Kenneth Clark: Malcolm X, one of the most articulate exponents of the Black Muslim philosophy, has said of your movement and your philosophy that it plays into the hands of the white oppressors, that they are happy to hear you talk about love for the oppressor, because this disarms the Negro and fits into the stereotype of the Negro as a meek, turning the other cheek sort of creature. Would you care to comment on Mr. X’s beliefs?

Martin Luther King Jr: Well, I don’t think of love as… in this context, as emotional bosh, but I think of love as something strong and that organizes itself into powerful direct action. This is what I’ve tried to teach in the struggle in the South. We are not engaged in a struggle that means we sit down and do nothing. There is a great deal of difference between non-resistance to evil and non-violent resistance.

Malcolm X: Martin Luther King is just a 20th century or modern Uncle Tom or a religious Uncle Tom, who is doing the same thing today to keep Negroes defenseless in the face of attack that Uncle Tom did on the plantation to keep those Negroes defenseless in the face of the attacks of the Klan in that day.

Martin Luther King Jr: I think, though, that we can be sure that the vast majority of Negroes who engage in the demonstrations, and who understand the non-violent philosophy, will be able to face dogs and all of the other brutal methods that they use, without retaliating with violence, because they understand that one of the first principles of non-violence is a willingness to be the recipient of violence, while never inflicting violence upon another.

Baldwin: As concerns Malcolm and Martin, I watched two men, coming from unimaginably different backgrounds, whose positions, originally, were poles apart, driven closer and closer together. By the time each died, their positions had become, virtually, the same position. It can be said, indeed, that Martin picked up Malcolm’s burden, articulated the vision which Malcolm had begun to see, and for which he paid with his life, and that Malcolm was one of the people Martin saw on the mountain-top. Medgar was too young to have seen this happen, though he hoped for it, and would not have been surprised. But Medgar was murdered first. I was older than Medgar, Malcolm and Martin. I was raised to believe that the eldest was supposed to be a model for the younger, and was, of course, expected to die first. Not one of these three lived to be forty.

Two, four, six eight, we don’t want to integrate! Two, four, six eight, we don’t want to integrate!

(indistinct shouting)

We want King! We want King! We want King!

(gunshot)

(screaming)

(shouting)

Malcolm X: We need an organization that no one downtown loves. We need one that’s ready and willing to take action, any kind of action, by any means necessary.

(applause)

Baldwin: When Malcolm talks, or one of the Muslim ministers talk, they articulate for all the Negro people who hear them, who listen to them, they articulate their suffering. The suffering which has been in this country so long denied. That’s Malcolm’s great authority over any of his audiences. He corroborates their reality. He tells them that they really exist, you know.

[FERGUSON, MISSOURI – AUGUST 2014]

(shouting)

(sirens blaring)

Officer: Get back. Get back!

I am!

(indistinct chanting)

I am!

(indistinct chanting)

(sirens blaring)

(explosions)

Baldwin: There are days, this is one of them… when you wonder… what your role is in this country and what your future is in it. How precisely are you going to reconcile… yourself to your situation here, and how you are going to communicate… to the vast, heedless, unthinking… cruel white majority that you are here. I’m terrified at the moral apathy, the death of the heart, which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human. I base this on their conduct, not on what they say. And this means that they have become, in themselves… moral monsters.

(indistinct chatter)

(cameras clicking)

Baldwin: Most of the white Americans I’ve ever encountered, really, you know, had a Negro friend or a Negro maid or somebody in high school, but they never, you know, or rarely, after school was over or whatever, came to my kitchen, you know. We were segregated from the schoolhouse door. Therefore, he doesn’t know, he really does not know, what it was like for me to leave my house, to leave the school and go back to Harlem. He doesn’t know how Negroes live. And it comes as a great surprise to the Kennedy brothers and to everybody else in the country. I’m certain, again, you know, that again like most white Americans I have encountered, they have no… I’m sure they have nothing whatever against Negroes… That’s really not the question. The question is really a kind of apathy and ignorance, which is the price we pay for segregation. That’s what segregation means. You don’t know what’s happening on the other side of the wall, because you don’t want to know.

Baldwin: I was in some way, in those years, without entirely realizing it, the great Black Hope of the great White Father. I was not a racist, or so I thought. Malcolm was a racist, or so they thought. In fact, we were simply trapped in the same situation.

[A RAISIN IN THE SUN, D. PETRIE – 1961 – FROM LORRAINE HANSBERRY’S PLAY]

Well, you tell that to my boy tonight, when you put him to sleep on the living room couch. And you tell it to him in the morning, when his mother goes out of here to take care of somebody else’s kids. And tell it to me, when we want some curtains or some drapes and you sneak out of here and go work in somebody’s kitchen. All I want is to make a future for this family. All I want is to be able to stand in front of my boy like my father never was able to do to me.

I must sketch now the famous Bobby Kennedy meeting.

Baldwin: Lorraine Hansberry would not be very much younger than I am now, if she were alive. At the time of the Bobby Kennedy meeting, she was thirty-three. That was one of the very last times I saw her on her feet, and she died at the age of thirty-four. I miss her so much.

People forget how young everybody was. Bobby Kennedy, for another, quite different example, was thirty-eight. We wanted him to tell his brother, the president, to personally escort to school, on that day or the day after, a small black girl, already scheduled to enter Deep South School. “That way,” we said, “it will be clear that whoever spits on that child will be spitting on the nation.” He didn’t understand this either. “It would be,” he said, “a meaningless moral gesture.” “We would like,” said Lorraine, “from you, a moral commitment”. He looked insulted, seemed to feel that he’d been wasting his time. Well, Lorraine sat still, watching all the while. She looked at Bobby Kennedy, who, perhaps for the first time, looked at her. “But I am very worried,” she said, “about the state of the civilization which produced that photograph of the white cop standing on that Negro woman’s neck in Birmingham.”

Then she smiled. And I am glad that she was not smiling at me. “Goodbye Mr. Attorney General,” she said, and turned and walked out of the room. And then, we heard the thunder.

[Lorraine Hansberry, 34, Dies, Author of ‘A Raising in the Sun’]

Baldwin: The very last time I saw Medgar Evers, he stopped at his house on the way to the airport so I could autograph my books for him, his wife and children. I remember Myrlie Evers standing outside, smiling, and we waved, and Medgar drove to the airport and put me on the plane. Months later, I was in Puerto Rico, working on my play. Lucien and I had spent a day or so wandering around the island, and now we were driving home.

(car radio playing)

Baldwin: It was a wonderful, bright, sunny day, the top to the car was down, we were laughing and talking, and the radio was playing. Then the music stopped…

(music stops)

Baldwin: …and a voice announced that Medgar Evers had been shot to death in the carport of his home, and his wife and children had seen the big man fall.

[DON’T LOOK BACK, D.A. PENNEBAKER – 1967]

♪ Medgar Evers was buried from the bullet he caught ♪

♪ They lowered him down as a king ♪

♪ But when the shadowy sun ♪

♪ Sets on the one ♪

♪ That fired the gun ♪

♪ He’ll see by his grave ♪

♪ On the stone that remains ♪

♪ Carved next to his name ♪

♪ His epitaph plain: ♪

♪ Only a pawn in their game ♪

Baldwin: The blue sky seemed to descend like a blanket. And I couldn’t say anything, I couldn’t cry. I just remembered his face, a bright, blunt, handsome face, and his weariness, which he wore like his skin, and the way he said “ro-aad” for road. And his telling me how the tatters of clothes from a lynched body hung, flapping in the tree for days, and how he had to pass that tree every day. Medgar. Gone.

♪ Baby, please don’t go ♪

♪ Baby, please don’t go ♪

♪ Baby, please don’t go Back to New Orleans ♪

♪ You know I love you so Baby, please don’t go ♪

(song continues)

Baldwin: In America, I was free only in battle, never free to rest, and he who finds no way to rest cannot long survive the battle.

(African singing and drumming)

Baldwin: And the young, white revolutionary remains, in general, far more romantic than a black one. White people have managed to get through entire lifetimes in this euphoric state, but black people have not been so lucky. A black man who sees the world the way John Wayne, for example, sees it… would not be an eccentric patriot, but a raving maniac. The truth is that this country does not know what to do with its black population, dreaming of anything like “The Final Solution”.

Baldwin: The Negro has never been as docile as white Americans wanted to believe. That was a myth. We were not singing and dancing down the levee. We were trying to keep alive, we were trying to survive a very brutal system. The n*gger has never been happy in his place.

Baldwin: One of the most terrible things, is that, whether I like it or not, I am an American. My school really was the streets of New York City. My frame of reference was… George Washington and John Wayne. But I was a child, you know, and when a child puts his eyes on the world, he has to use what he sees. There’s nothing else to use. And you are formed by what you see, the choices you have to make, and the way you discover what it means to be black in New York and then throughout the entire country.

(gun clicks)

Baldwin: I know how you watch, as you grow older, and it’s not a figure of speech, the corpses of your brothers and your sisters pile up around you. And not for anything they have done. They were too young to have done anything. But what one does realize is that when you try to stand up and look the world in the face like you had a right to be here, you have attacked the entire power structure of the western world. Forget “The Negro Problem”. Don’t write any voting acts. We had that. It’s called The Fifteenth Amendment. During the Civil Rights Bill of 1964, what you have to look at is what is happening in this country, and what is really happening is that brother has murdered brother, knowing it was his brother. White men have lynched Negroes, knowing them to be their sons. White women have had Negroes burned, knowing them to be their lovers. It is not a racial problem. It’s a problem of whether or not you’re willing to look at your life and be responsible for it, and then begin to change it. That great western house I come from is one house, and I am one of the children of that house. Simply, I am the most despised child of that house. And it is because the American people are unable to face the fact that I am flesh of their flesh, bone of their bone, created by them. My blood, my father’s blood, is in that soil.

[IMITATION OF LIFE, J.M. STAHL – 1934]

Good afternoon, Ma’am. It’s raining so hard, I brought rubbers and coat to fetch my little girl home.

I’m afraid you’ve made some mistake.

Ain’t this the 3B?

Yes.

Well, this is it.

It can’t be it. I have no little colored children in my class.

Oh, thank you.

There’s my little girl.

Peola, you may you home.

Boy: Gee, I didn’t know she was colored.

Girl: Neither did I.

Peola: I hate you, I hate you, I hate you!

Woman: Peola! Peola!

Baldwin: I know very well that my ancestors had no desire to come to this place. But neither did the ancestors of the people who became white, and who require of my captivity a song. They require a song of me, less to celebrate my captivity than to justify their own.

PURITY

Baldwin: I have always been struck, in America, by an emotional poverty so bottomless, and a terror of human life, of human touch, so deep that virtually no American appears able to achieve any viable, organic connection between his public stance and his private life. This failure of the private life has always had the most devastating effect on American public conduct, and on black-white relations. If Americans were not so terrified of their private selves, they would never have become so dependent on what they call “The Negro Problem”.

[NO WAY OUT, J. MANKIEWICZ – 1950]

They said it wasn’t nice to say “n*gger”. N*gger! N*gger! N*gger! Poor little n*gger kids, love the little n*gger kids. Who loved me? Who loved me?

Baldwin: This problem, which they invented in order to safeguard their purity, has made of them criminals and monsters, and it is destroying them.

(band playing)

Baldwin: And this, not from anything Blacks may or may not be doing, but because of the role of a guilty and constricted white imagination has assigned to the Blacks.

[THE DEFIANT ONES, S. KRAMER – 1958]

Look man, don’t give me that look. You should have got what was coming to you after spitting in that guy’s face. Why you…

Baldwin: It is impossible to accept the premise of the story, a premise based on the profound American misunderstanding of the nature of the hatred between black and white.

Man: That time is now.

(grunts)

Baldwin: The root of the black man’s hatred is rage, and he does not so much hate white men as simply wants them out of his way, and more than that, out of his children’s way.

(both panting)

Baldwin: The root of the white man’s hatred is terror.

(grunts)

I’m gonna kill you.

Baldwin: A bottomless and nameless terror, which focuses on this dread figure, an entity which lives only in his mind.

Run! Come on!

I can’t make it, I can’t make it!

Baldwin: When Sidney jumps off the train, the white liberal people downtown were much relieved and joyful. But when black people saw him jump off the train, they yelled, “Get back on the train, you fool!” The black man jumps off the train in order to reassure white people, to make them know that they are not hated, that though they have made human errors, they done nothing for which to be hated.

♪ I’m Chiquita Banana And I’m here to say ♪

♪ I am the top banana… ♪

Baldwin: In spite of the fabulous myths proliferating in this country concerning the sexuality of black people, black men are still used, in the popular culture, as though they had no sexual equipment at all. Sidney Poitier, as a black artist, and a man, is also up against the infantile, furtive sexuality of this country. Both he and Harry Belafonte, for example, are sex symbols, though no one dares admit that, still less to use them as any of the Hollywood he-men are used. Black people have been robbed of everything in this country…

[GUESS WHO’S COMING TO DINNER, S. KRAMER – 1967]

I’ve got something to say to you, boy.

Baldwin: …and they don’t want to be robbed of their artist. Black people particularly disliked Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, because they felt that Sidney was, in effect, being used against them. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner may prove, in some bizarre way, to be a milestone, because it is really quite impossible to go any further in that particular direction.

♪ If you ever plan to motor West… ♪

Baldwin: The next time, the kissing will have to start.

[IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT, N. JEWISON – 1967]

Well, you’ve got your ticket? Here you are. Thank you.

Baldwin: I am aware that men do not kiss each other in American films, nor, for the most part, in America nor do the black detective and the white Sheriff kiss here.

You take care, you hear?

Yeah.

Baldwin: But the obligatory, fade-out-kiss, in the classic American film, did not speak of love, and still less of sex. It spoke of reconciliation, of all things now becoming possible.

(rain pouring)

(windscreen wipers thudding)

Baldwin: I knew a blond girl in the village a long time ago, and eventually, we never walked out of the house together.

[PRESSURE, H. OVE – 1976]

Baldwin: She was far safer walking the streets alone than when walking with me. A brutal and humiliating fact which thoroughly destroyed whatever relationship this girl and I might have been able to achieve. This happens all the time in America, but Americans have yet to realize what a sinister fact this is, and what it says about them. When we walked out in the evening, then, she would leave ahead of me, alone. I would give about five minutes, and then I would walk out alone, taking another route, and meet her on the subway platform. We would not acknowledge each other. We would get into the subway car, sitting at opposite ends of it, and walk, separately, through the streets of the free and the brave, to wherever we were going… a friend’s house, or the movies.

[THE SECRET OF SELLING THE NEGRO]

Man: All over the country, families such this are enjoying new prosperity. They have new interests, news standards of living, a buying power they’ve never enjoyed before. There are good prospects for practically all types of goods and services. All too often though, they are overlooked prospects. Since 1940, in San Francisco alone, the Negro market has increased by 89%. Here are millions of customers for what you have to sell. Customers with 15 billion dollars to spend

Baldwin: Someone once said to me that the people in general cannot bear very much reality. He meant by this that they prefer fantasy to a truthful recreation of their experience. People have quite enough reality to bear, by simply getting through their lives, raising their children, dealing with the eternal conundrums of birth, taxes, and death.

[Bob Kennedy] Negroes are continuously making progress here in this country. The progress in many areas is not as fast as it should be, but they are making progress, and we will continue to make progress. There’s no reason that they, in a near and foreseeable future, that a Negro could also be president of the United States.

Baldwin: I remember, for example, when the ex-Attorney General, Mr. Robert Kennedy, said that it was conceivable that in 40 years in America, we might have a Negro president. And that sounded like a very emancipated statement, I suppose, to white people. They were not in Harlem… when this statement was first heard. I did not hear, and possibly will never hear, the laughter and the bitterness and the scorn with which this statement was greeted. From the point of view of the man in the Harlem barbershop, Bobby Kennedy only got here yesterday. And now he’s already on his way to the Presidency. We’ve been here for 400 years and now he tells us that maybe in 40 years, if you’re good, we may let you become president.

♪ It was a dream, Just a dream I had on my mind ♪

♪ It was a dream, Just s dream I had on my mind ♪

♪ And when I woke up, baby ♪

♪ Not a thing could I find ♪

(cheering and applause)

♪ I dreamed I was an angel And had a good time ♪

♪ I dreamed I was satisfying And nothin’ to worry my mind ♪

♪ But it was a dream ♪

♪ Just a dream I had on my mind ♪

SELLING THE NEGRO

Baldwin: Let me put it this way, that from a very literal point of view, the harbors and the ports and the railroads of the country, the economy, especially in the southern states, could not conceivably be what it has become if they had not had, and do not still have, indeed, and for so long, so many generations, cheap labor.

(Western music playing)

Baldwin: It is a terrible thing for an entire people to surrender to the notion that one ninth of its population is beneath them. And until that moment, until the moment comes, when we, the Americans, we, the American people, are able to accept the fact that I have to accept, for example, that my ancestors are both white and black. That on that continent we are trying to forge a new identity for which we need each other, and that I am not a ward of America. I am not an object of missionary charity, I am one of the people who built the country. Until this moment, there is scarcely any hope for the American Dream, because people who are denied participation in it, by their very presence… will wreck it. And if that happens, it is a very grave moment for the West. Thank you.

(applause)

[AUGUST 1963 – HOLLYWOOD ROUNDTABLE]

David Schoenburn: We’re here in the studio today with seven men who have two things in common: they are entertainers and artists; and they’ve all come to Washington. They are seven out of some two hundred thousand American citizens who came to the capital to march for freedom and for jobs. Will this tremendous outburst now lead to a course of action, Mr. Belafonte?

Belafonte: The now that is being spoken about is the fact that in a hundred years, finally, through whatever the causes have been in history, and most of them have been because of oppression, the Negro people have strongly and fully taken the bit in their teeth, they’re asking absolutely no quarter from anyone. But I do say that the bulk of the interpretation of whether this thing is going to end successfully and joyously, or is going to end disastrously, lays very heavily with the white community, it lays very heavily with the profiteers, it lays very heavily with the vested interests. It lays very heavily with a great middle stream in this country, of people who have refused to commit themselves, or even have the slightest knowledge that these things have been going on.

Baldwin: I am speaking as a member of a certain democracy in a very complex country, which insists on being very narrow-minded. Simplicity is taken to be a great American virtue, along with sincerity.

I am sorry.

I am deeply sorry.

And I am sorry.

I’m deeply sorry about that.

They are no excuses.

I am solely…

We have made plenty of mistakes.

For that, I apologize.

I am very sorry.

I’m sorry I did this to you, but you gotta get used to it. It’s one of those little problems in life.

I take full responsibility.

I’m here today to again apologize.

I’ll just apologize for that to her.

For any mistakes I’ve made, I take full responsibility. It’s an honor to serve the city of Ferguson and the people who live there.

Baldwin: One of the results of this is that immaturity is taken to be a virtue too. So that someone like that, let’s say John Wayne, who spent most of his time on screen admonishing Indians, was in no necessity to grow up.

Baldwin: I had been in London on this particular night. We were free and we decided to treat ourselves to a really fancy, friendly dinner. The head waiter came and said there was a phone call for me, and my sister Gloria rose to take it. She was very strange when she came back. She didn’t say anything, and I began to be afraid to ask her anything. Then, nibbling at something she obviously wasn’t tasting, she said, “Well, I’ve got to tell you because the press is on its way over here. They have just killed Malcolm.

Baldwin: There is nothing in the evidence offered by the book of the American republic, which allows me really to argue with the cat who says to me, “They needed us to pick the cotton, and now they don’t need us anymore. Now they don’t need us, they’re gonna kill us all off, just like they did the Indians”. And I can’t say it’s a Christian nation, though your brothers will never do that to you, because the record is too long and too bloody. That’s all we have done. All your buried corpses now begin to speak.

[JULY 1967 – H. RAP BROWN, BLACK PANTHER PARTY]

I say violence is necessary. Violence is a part of America’s culture. It is as American as cherry pie.

Black power, Brothers.

(cheering and applause)

[OAKLAND – 1968]

(indistinct shouting)

(indistinct shouting)

Baldwin: If we were white, if we were Irish, if we were Jewish, if we were Poles, if we had, in fact, in your mind, a frame of reference, our heroes would be your heroes too. Nat Turner would be a hero for you instead of a threat. Malcolm X might still be alive. Everyone is very proud of brave little Israel, against which I have nothing, I don’t want to be misinterpreted, I’m not an anti-Semite. But, you know, when the Israelis pick up guns, or the Poles, or the Irish, or any white man in the world says, “Give me liberty, or give me death”, the entire white world applauds. When a black man says exactly the same thing, word for word, he is judged a criminal and treated like one and everything possible is done to make an example of this bad n*gger, so there won’t be any more like him.

[THE LAND WE LOVE, US GOVERNMENT FILM – 1960]

Man: Look out across this land we love, look about you whatever you are, this unending scenic beauty, and there’s freedom, it’s an inherent American right meaning many different things to every single citizen. It’s a leisurely afternoon of golf along a pleasant course. It’s an amusement park, a rollercoaster ride. A day at the county fair.

(fire crackling)

[WATTS PROTESTS, LOS ANGELES – AUGUST 1965]

A day of excitement, unrestricted travel across all our 50 states, unlimited enjoyment of all these jewels in the continent’s crown. For all of us, there’s all of America, in all of its scenic beauty, all of its heritage of history, all of its limitless opportunity…

Martin Luther King Jr: We’ve dropped too many bombs on Vietnam now.

(applause)

Martin Luther King Jr: Let us save our national honor! Stop the bombing, and stop the war!

Baldwin: What I am trying to say to this country, to us, is that we must know this. We must realize this, that no other country in the world have been so fat and so sleek, and so safe, and so happy, and so irresponsible, and so dead. No other country can afford to dream of a Plymouth and a wife and a house with a fence, and the children growing up safely to go to college and to become executives, and then to marry, and have the Plymouth and the house and so forth. A great many people do not live this way, and cannot imagine it, and do not know that when we talk about “democracy”, this is what we mean.

(audience cheering)

Baldwin: The industry is compelled, given the way it is built, to present to the American people a self-perpetuating fantasy of American life. Their concept of entertainment is difficult to distinguish from the use of narcotics.

What worries you about them having black partners? Do you think people are gonna look down on them, or judge them?

Yes, I think people look down.

(cheering)

Baldwin: To watch the TV screen for any length of time is to learn some really frightening things about the American sense of reality. We are cruelly trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are. And we cannot possibly become what we would like to be until we are willing to ask ourselves just why the lives we lead on this continent are mainly so empty, so tame, and so ugly. These images are designed not to trouble, but to reassure. They also weaken our ability to deal with the world as it is, ourselves as we are.

Nick Cavett: I would like to add someone to our group here, Professor Paul Weiss, the sterling professor of philosophy at Yale.

(applause)

(piano music playing)

Nick Cavett: Were you able to listen to the show backstage?

Professor Paul Weiss: I heard a good deal of it, but then I was behind the whatsitmajig.

Cavett: Yes.

Weiss: So I heard only some of it.

Cavett: Did you hear anything that you disagreed with?

Weiss: I disagreed with a great deal of it, and of course, there’s a good deal I agree with. But I think he’s overlooking one very important matter, I think. Each one of us, I think, is terribly alone. He lives his own individual life. He has all kind of obstacles, the way of religion or color or size or shape or lack of ability, and the problem is to become a man.

Baldwin: But what I was discussing was not that problem, really. I was discussing the difficulties, the obstacles, the very real danger of death thrown up by the society when a Negro, a black man, attempts to become a man.

All this emphasis upon black man and white, does emphasize something which is here, but it emphasizes, or perhaps exaggerates it, and therefore makes us put people together in groups which they ought not to be in. I have more in common with a black scholar than I have with a white man who is against scholarship. And you have more in common with a white author than you have with someone who is against all literature. So why must we always concentrate on color, or religion, or this? There are other ways of connecting men.

Baldwin: I’ll tell you this. When I left this country in 1948, I left this country for one reason only, one reason… I didn’t care where I went. I might’ve gone to Hong Kong, I might have gone to Timbuktu. I ended up in Paris, on the streets of Paris, with 40 dollars in my pocket and the theory that nothing worse could happen to me there than had already happened to me here. You talk about making it as a writer by yourself, you have to be able then to turn up all the antennae by which you live, because once you turn your back on this society, you may die. You may die.

(applause)

Baldwin: And it’s very hard to sit at a typewriter, and concentrate on that, if you are afraid of the world around you. The years I lived in Paris did one thing for me: they released me from that particular social terror, which was not the paranoia of my own mind, but a real social danger visible in the face of every cop, every boss, everybody.

(audience applaud)

Baldwin: I don’t know what most white people in this country feel. But I can only include what they feel from that state of their institutions. I don’t know if white Christians hate Negroes or not, but I know we have a Christian church which is white and a Christian church which is black. I know, as Malcolm X once put it, the most segregated hour in American life is high noon on Sunday. That says a great deal for me about a Christian nation. It means I can’t afford to trust most white Christians and I certainly cannot trust the Christian church. I don’t know whether the labor unions and their bosses really hate me. That doesn’t matter, but I know I’m not in their unions. I don’t know if the Real Estate Lobby has anything against black people, but I know the Real Estate Lobby is keeping me in the ghetto. I don’t know if the board of education hates black people, but I know the textbooks they give my children to read, and the schools that we have to go to. Now, this is the evidence. You want me to make an act of faith, risking myself, my wife, my woman, my sister, my children, on some idealism which you assure me exists in America, which I have never seen.

(applause)

Weiss: Hold on a second.

[UNCLE TOM’S CABIN, H.A. POLLARD – 1927]

Baldwin: All of the Western nations have been caught in a lie, the lie of their pretended humanism. This means that their history has no moral justification, and that the West has no moral authority.

(inaudible)

Baldwin: “Vile as I am,” states one of the characters in Dostoevsky‘s The Idiot, “I don’t believe in the wagons that bring bread to humanity. For the wagons that bring bread to humanity, may coldly exclude a considerable part of humanity from enjoying what is brought.”

[THE PAJAMA GAME, G. ABBOTT, S. DONEN – 1957]

(excited cheers)

Baldwin: For a very long time, America prospered. This prosperity cost millions of people their lives. Now, not even the people who are the most spectacular recipients of the benefits of this prosperity are able to endure these benefits. They can neither understand them nor do without them. Above all, they cannot imagine the price paid by their victims, or subjects, for this way of life, and so they cannot afford to know why the victims are revolting.

(gunshots)

(screams)

Down!

On the ground! Get on the ground, now!

Man: Damn, man!

(screaming)

Baldwin: This is the formula for a nation or a kingdom decline. For no kingdom can maintain itself by force alone. Force does not work the way its advocates think in fact it does.

[CUSTER OF THE WEST, R. SIODMAK – 1967]

(yelling)

(gunshots)

Baldwin: It does not, for example, reveal to the victim the strength of the adversary.

[SOLDIER BLUE, R. NELSON – 1970]

(screams)

(gunshots)

Baldwin: On the contrary, it reveals the weakness, even the panic, of the adversary. And this revelation invests the victim with passion.

[WOUNDED KNEE MASSACRE, 1890]

Baldwin: There is a day in Palm Springs that I will remember forever, a bright day. I was based in Hollywood, working on the screen version of the autobiography of Malcolm X. This was a difficult assignment, since I had known Malcolm, after all, crossed swords with him, worked with him, and held him in that great esteem which is not easily distinguishable, if it is distinguishable, from love. Billy Dee Williams had come to town and he was staying at the house. I very much wanted Billy Dee for the role of Malcolm. The phone had been brought out to the pool, and now it rang. And I picked up. The record player was still playing. “He’s not dead yet, but it’s a head wound.”

[Bob Kennedy] I have some very sad news for all of you, and I think sad news for all our fellow citizens and people who love peace all of over the world. And that is that Martin Luther King was shot and was killed tonight.

(crowd scream)

Baldwin: I hardly remember the rest of the evening at all. I remember weeping, briefly, more in helpless rage than in sorrow, and Billy trying to comfort me. But I really don’t remember that evening at all.

♪ Mother dear, May I go downtown ♪

♪ Instead of out to play, ♪

♪ And march the streets of Birmingham ♪

♪ In a Freedom March today? ♪

♪ But Mother, I won’t be alone ♪

♪ Other children will go with me, ♪

♪ And march the streets of Birmingham ♪

♪ To make my country free ♪

Baldwin: The church was packed. In the pew before me sat Marlon Brando, Sammy Davis, Eartha Kitt. Sidney Poitier nearby. I saw Harry Belafonte sitting next to Coretta King. I have a childhood hand over thing about not weeping in public. I was concentrating on holding myself together. I did not want to weep for Martin. Tears seemed futile. But I may also have been afraid, and I could not have been the only one, that if I began to weep, I would not be able to stop. I started to cry, and I stumbled. Sammy grabbed my arm. The story of the Negro in America is the story of America. It is not a pretty story. What can we do? Well, I am tired. I don’t know how it will come about, I know that no matter how it comes about, it will be bloody, it will be hard. I still believe that we can do with this country something that has not been done before. We are misled here because we think of numbers. You don’t need numbers, you need passion. And this is proven by the history of the world. The tragedy is that most of the people who say they care about it do not care. What they care about is their safety and their profits.

♪ When I was laying in jail ♪

♪ With my back turned to the wall ♪

♪ When I was laying in jail ♪

♪ With my back turned to the wall ♪

♪ I just laid down and dreamed I could… ♪

Baldwin: The American way of life has failed to make people happier, or make them better. We do not want to admit this, and we do not admit it. We persist in believing that the empty and criminal among our children are the result of some miscalculation in the formula that can be corrected. That the bottomless and aimless hostility which makes our cities among the most dangerous in the world is created and felt by a handful of aberrants, that the lack, yawning everywhere in this country, of passionate conviction, of personal authority, proves only our rather appealing tendency to be gregarious and democratic. To look around the United States today, is enough to make prophets and angels weep. This is not the land of the free. It is only very unwillingly and sporadically…

[ELEPHANT, GUS VAN SANT – 2003]

(gun clicks)

Baldwin: …the home of the brave.

(gunshot)

(screaming)

(gunshot)

(screaming)

(sobbing)

(gunshot)

(camera clicks)

Baldwin: I sometimes feel it to be an absolute miracle that the entire black population of the United States of America has not long ago succumbed to raging paranoia. People finally say to you, in an attempt to dismiss the social reality, “But you’re so bitter!”

[RODNEY KING BEATING, LOS ANGELES – MARCH 1991]

Baldwin: Well, I may or may not be bitter, but if I were, I would have good reasons for it. Chief among them that American blindness, or cowardice, which allow us to pretend that life presents no reasons for being bitter.

[LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON, B. WILDER – 1957]

Baldwin: In this country, for a dangerously long time, there have been two levels of experience. One, to put it cruelly, can be summed up in the images of Gary Cooper and Doris Day, two of the most grotesque appeals to innocence the world has ever seen.

[LULLABY OF BROADWAY, D. BUTLER – 1951]

Baldwin: And the other, subterranean, indispensable, and denied, can be summed up, let us say, in the tone and in the face of Ray Charles.

♪ Hey mama, Don’t you treat me wrong ♪

♪ Come and love your daddy All night long ♪

♪ I know it’s all right now Hey, hey ♪

♪ When you see me in misery ♪

♪ Come on baby, see about me ♪

Baldwin: There has never been any genuine confrontation between these two levels of experience.

[LOVER COME BACK, D. MANN – 1961]

♪ Should I be bad ♪

♪ Or nice? ♪

♪ Should I surrender? ♪

♪ His pleading words so tenderly ♪

♪ Entreat me ♪

♪ Is this the night that love ♪

♪ Finally defeats me? ♪

Baldwin: You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettos without becoming something monstrous yourselves. And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage. You never had to look at me. I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.

I AM NOT A N*GGER

Baldwin: History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals. I attest to this. The world is not white. It never was white, cannot be white. White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.

Baldwin: I can’t be a pessimist, because I’m alive. To be a pessimist means you have agreed that human life is an academic matter, so I’m forced to be an optimist. I am forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive. But… the Negro in this country… the future of the Negro in this country… is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country. It is entirely up to the American people and our representatives. It is entirely up to the American people whether or not they are going to face and deal with and embrace the stranger they have maligned so long. What white people have to do is try to find out, in their own hearts, why it was necessary to have a “n*gger” in the first place, because I’m not a n*gger, I’m a man. But if you think I’m a n*gger, it means you need him. The question you’ve got to ask yourself, the white population of this country has got to ask itself, North and South, because it’s one country, and for the Negro, there is no difference between the North and the South… it’s just a difference in the way they castrate you, but the fact of the castration is American fact. If I’m not the n*gger here and you invented him, you the white people invented him, then you’ve got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that, whether or not it’s able to ask that question.

♪ (“The Blacker the Berry” by Kendrick Lamar plays) ♪