by Oriana Fallaci

I have known Fellini for many years; to be precise, ever since I met him in New York for the American premiere of his movie The Nights of Cabiria, at which time we became good friends. In fact, we often used to go to eat steaks at Jack’s or roast chestnuts in Times Square, where you could also do target shooting. Then, from time to time, he would turn up at the apartment I shared in Greenwich Village with a girl called Priscilla to ask for a cup of coffee. The homely brew would alleviate, though I never understood why, his nostalgia for his homeland and his misery at his separation from his wife Giulietta. He would come in frantically massaging his knee, “My knee always hurts when I’m sad. Giulietta! I want Giulietta!” And Priscilla would come running to have a look at him as I’d have gone running to have a look at Greta Garbo. Needless to say, in those days there was nothing of Greta Garbo about Fellini, he wasn’t the monument he is today. He used to call me Pallina, Little Ball. He made us call him Pallino, sometimes Pallone, Big Ball. He would go in for innocent extravagances such as weeping in the bar of the Plaza Hotel because the critic of the New York Times had given him a bad review, or playing the hero. He used to go around with a gangster’s moll, and every day the gangster would call him at his hotel, saying, “I will kill you.” He didn’t understand English and would reply, “Very well, very well,’’ so adding to his heroic reputation. His reputation lasted until I explained to him what “I will kill you” meant. Within half an hour Fellini was on board a plane making for Rome.

He used to do other things too, such as wandering around Wall Street at night, casing the banks like a robber, arousing the suspicions of the world’s most suspicious police, so that finally they asked to see his papers, arrested him because he wasn’t carrying any, and shut him up for the night in a cell. He spent his time shouting the only English sentence he knew: “I am Federico Fellini, famous Italian director.” At six in the morning an Italian-American policeman who had seen La Strada I don’t know how many times said, “If you really are Fellini, come out and whistle the theme music of La Strada Fellini came out and in a thin whistle—he can’t distinguish a march from a minuet—struggled through the entire soundtrack. A triumph. With affectionate punches in the stomach that were to keep him on a diet of consommé for the next two weeks, the policemen apologized and took him back to his hotel with an escort of motorcycles, saluting him with a blare of horns that could be heard as far away as Harlem. In those days Fellini was truly simpatico, and I liked him very much.

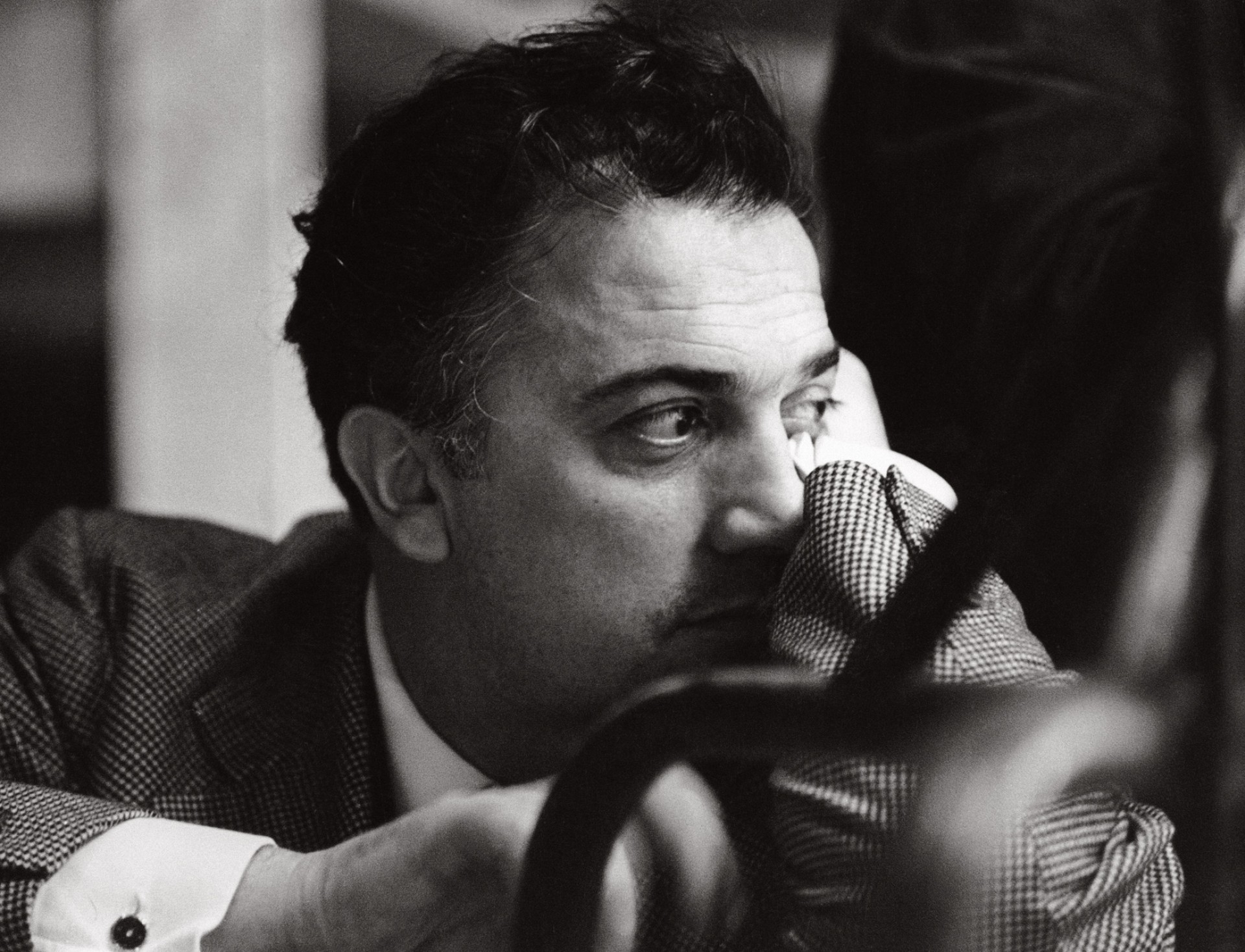

When I approached him for this interview, he was a little less so, although he greeted me, as was his wont, by swinging me off my feet in a passionate hug, pinching and squeezing me from my neck to my knees, swearing that if he wasn’t already married to Giulietta he would immediately have married me. “Come to think of it, why weren’t we in love in New York? Ah, how cruel of you not to have given yourself to me.” And he pretended to have forgotten, of course, that not once during the course of our escapades in New York had he shown me the slightest sign of romance, that never had he made a single adulterous suggestion to distract us from our respective flirtations. He had made La Dolce Vita, a movie for which he had been compared with Shakespeare, he was about to present 8½. a movie that was being talked about as if it were the Divine Comedy. And, while not actually admitting it. he was fully aware of the glory that surrounded him: he thrust out his jaw rather like Mussolini, his eyes were serious, one knew that one could no longer tall him Pallino or Pallone. Besides, once the hugging was over, he made it clear to me almost immediately. He had agreed to see me, he said, only because it was me: he had very little time, and the only way he could grant the interview was by doing it as he ate. That was why he had invited me to the restaurant we were then entering.

I tried to talk him out of such an awful plan. The tape recorder was electric, and there was no electric outlet, or if there was, it wasn’t neat our table. My complaints were all to no avail. Either we did it in the restaurant while we ate or nowhere else and never again. So I looked for a table next to a plug, made room for the tape recorder among the plates and the glasses and the hors d’oeuvres platter, and started the interview, which, since we were constantly interrupted by innumerable telephone calls, proceeded as smoothly as a lame man running, against the clatter and noise of forks, glasses, and vulgar chewing. When I played back the tape, phrases came out like this: “With this movie I am trying to say … Do you want the ham or the salami? I’ll take the salami. People who talk about metaphysical dialectics… No, I don’t want any pasta, it’s too fattening. A steak without salt, that’s what I’ll have… It’s so stupid to shut one’s eyes to the mystery.” . . . Crack! Clink! Clink! . . . “The silence that surrounds you and becomes a gleam of light . . . french fries! Why aren’t you having any french fries?” Without a doubt it would all have to be done again. And sighing, groaning, Fellini said all right. Seeing it was for me, he would come to my hotel next day at ten. “But we shan’t be quiet in the hotel. Federico.” “Yes, we shall. I’ll come up to your room.”

My room in the Excelsior wasn’t exactly a large one, and a double bed almost filled it. Knowing the way a bed can seduce Federico Fellini, I mean to sleep of course, I asked the manager for a suite with a silting room: “I am expecting Fellini.” “Fellini, Miss Fallaci? Oh! But of course! Yes, yes! And they gave me the suite in which the Shah of Persia and Soraya had stayed, with a sitting room that was more like a ballroom. Thither I removed, at hideous expense, and at half-past nine the following morning I was all ready to receive him, with cigarettes on one table, flowers on another, a waiter ready to bring us coffee—”Signor Fellini likes it strong and hot, please remember.” I felt like a seducer waiting to reveal the marvels of sex to his latest victim, all that was missing was a little violin music. But ten o’clock came and of Fellini never a trace. Eleven o’clock came and went, then midday, one o’clock, two o’clock, but from Fellini never a word. The telephone rang when it was past three-thirty and I was swallowing, along with my mortification, some tea and cookies. “Little treasure, little love, little Oriana, baby, I’ve been trying to ring you since this morning to tell you I’ll be late. But where are you, where do you keep going, why do you never stay in the hotel? Never mind, I forgive you, and I’ll be with you at five, not a moment later.”

Quite convinced, I replaced the receiver. He was a liar, but he would come. I went down to get a breath of fresh air. “And Fellini?” the hall porter inquired with an indefinable smile. “He’ll be here at five,” I replied grandly. But five o’clock came, and Fellini didn’t. Nor did he come at six, nor at seven, nor at eight, and as darkness descended on the sitting room where Reza Pahlevi had stayed and on my disappointed expectations, on my crushed prestige. on the ever more irritating impatience of my editor, who kept calling from Milan, saying, “Well, how far have we got- Well, has he come?” the telephone rang like a liberator. “Little treasure, little love, little Oriana, baby… An unforeseen complication had prevented him. physically prevented him. from coming to see me. He was pained, embarrassed, but I knew he was a man with a thousand things on his hands. To anyone else he would have said, “Forget it.” It was quite something that he wasn’t refusing altogether. that he was only putting it off However, he would see me that very evening at eleven o’clock at the private showing of the movie in Via Margutta. “Listen, Federico, I’m already late with this, at least two days late, my editor is angry, the pages are being kept open, listen Federico . . .” “Ah! How dare you doubt my word?!? How could you think I wouldn’t come?!? It’s insulting, wicked…”

So there I am, at eleven o’clock at night, waiting with my tape recorder in a doorway on Via Margutta for Federico Fellini, famous Italian director. I know he won’t come at eleven, but I wait for him. I know he won’t even come at midnight, but I wait for him. I know he won’t come at one o’clock either, but I wait for him. In the projection room the movie began an hour ago, an hour and a half, two. two and a half hours ago. it’s over, the people are coming out. stopping for refreshments, the refreshments are over, too, the people are going away, somebody closes the big door, I move onto the sidewalk, I go on waiting, with my eves closing, my legs giving way. Pestered by young punks, I go on waiting, until a taxi comes by, and I get in it. By now it’s half-past one in the morning. On my way in I tell the hotel porter to book me on the first flight to Milan. In my room I drop exhausted onto my bed. I fall asleep instantly. I wake up at the sound of the telephone. A mellifluous voice sings: “Little treasure, little love, little Oriana, baby, why didn’t you come?!” “Because I’m going,” I tell him. “I had to pack my bags. My plane takes off at eight in the morning.” “But that’s my plane! I’m leaving at eight, too! Isn’t that extraordinary? Isn’t that convenient? We’ll talk in the plane.” Needless to say, he missed the plane. Oh, he had his ticket, and a seat reservation too. That was his flight all right, columnists and photographers were waiting for him in Milan, his producer had sent his Cadillac and driver to meet him so he wouldn’t get lost. But he missed the plane all the same. And when it landed at Linate, the photographers came running to the steps, and coming down the steps were myself, two Americans from Oklahoma, four Frenchmen from Mines, and two Lombardian industrialists who dealt in chemical fertilizers and suchlike. Fellini arrived at midday, and a friend conveyed my message of welcome: that he could go to hell and stay there— providing they’d accept him, which was doubtful.

Italians and Chinese. Norwegians and Chileans, Mexicans and Frenchmen. Indians and Greenlanders, people of the world, remember this. You mustn’t send Federico Fellini to hell because Federico Fellini gets angry, he gets as angry as a wild beast and telephones you to heap insults on your grandfather, your mother, your aunt, your grandmother, your in-laws, your nephews, your cousins, and to remind you that he is a great director, an artist, a very great artist, and that by virtue of this he can miss all the appointments he wants, miss all the planes he wants—in fact, the planes would do well to wait for him. because one waits for Federico Fellini, we are all born to wait for Federico Fellini, etc. I was at the newspaper office when he telephoned, and he was shouting so loudly that everyone could hear him reminding me that Federico Fellini was a great director, an artist, a very great artist, bellowing in a voice that would have frightened to death the gangster who had frightened him to death, insulting me. whilst I imagined his Mussolini-like jaw. his saliva covering the telephone like dew. his big face sweaty with anger and horror at the blasphemy I had dared to commit. I tried to turn aside his insults with politesse, to explain to him what I thought of him at that moment. He didn’t hear me. he wasn’t listening. And while everyone was laughing and passing comments on his yells. I gently replaced the receiver.

Then began a crisis, for he isn’t a bad man. I swear. It was his misfortune to have such good luck, that’s all. Not even Saint Anthony could resist the scourge of so much good fortune, and it aroused the Emilian violence that lurked beneath that peaceful cat-like appearance. But afterward he is very, very sorry, to the point of tears. He is ready to call on a hundred people to tell you that his heart is rent with anguish, that he loves you as he loves Giulietta, that he’s always loved you. that he’ll love you as long as he lives—until, like someone hypnotized or sleepwalking, you find yourself getting into the Cadillac he has sent to fetch you, driving along the road thinking that it has been your fault and not his at all, entering the elevator wondering how he will ever forgive you, and finally opening the door of his hotel room looking like Judas after selling Christ. Here you find him stretched out like Ibn Sand on a bed, blissfully purring, saying in that mellifluous voice, “Little treasure, little love, little Oriana, baby . . Then you are clasped in a grim hug and begin to listen to him throughout a still grimmer evening.

Fellini wanted to read over the interview that follows, and he read it over three times, each time making various corrections to his answers, adding new opinions, making last minute reversals. This is the least genuine interview in the book, every single sentence in it has been revised and re-revised. The Napoleonic Code and the American Constitution assuredly cost less effort than this precious document.

I used to be truly fond of Federico Fellini. Since our tragic encounter I’m a lot less fond. To be exact, I am no longer fond of him. That is, I don’t like him at all. Glory is a heavy burden, a murdering poison, and to bear it is an art. And to have that art is rare.

Oriana Fallaci: So then let us brace ourselves, Signor Fellini, and let us discuss Federico Fellini, just for a change. I know you find it hard: you are so withdrawing, so secretive, so modest. But it is our duty to discuss him, for the sake of the nation, too. It won’t be long now before the story of your life and the meaning of your art become subjects taught in every state school, like mathematics, geography, religion. Haven’t the textbooks already been written? Federico Fellini, The Story of Federico Fellini, The Mystery of Fellini…. Not even about Giuseppe Verdi has so much been written. But then you are the Giuseppe Verdi of today. You even look alike, especially the hat. No, please, why are you hiding your hat? Giuseppe Verdi used to wear one just like it: black, broad- brimmed…

Federico Fellini: Nasty liar. Rude little bitch.

Why? Verdi was great, too, you know. The opening nights of his operas were exactly like your film premieres. I believe that only over La Traviata have the Italians ever made the fuss they did over your 8½, with seats booked months in advance, the ladies in new dresses, the critics plaiting laurel wreaths…

Oh yes… As if The White Sheik hadn’t been a howling failure, and Il Bidone hadn’t been given an icy reception, and La Strada hadn’t been greeted with ridicule and insults. And La Dolce Vita? Do you suppose it had nothing but praise and admiration? Eh, kid?

Heavens. In Milan somebody spat. In Rome the police intervened. But even Verdi had vegetables and raw eggs thrown at him from time to time. Signor Fellini! You aren’t worried by any chance? Forgive me, but seeing you so placidly stretched out on the bed, looking like a pussy cat, you seemed so calm…

I am, very calm. After all, I’ve done what I meant to do. I managed not to worry too much about whether or not people will like the movie. The waiting doesn’t leave me cold, obviously. But it doesn’t affect me in the way you might think. The anguish and the trepidation I feel are the same as when I made my first movie. I mean that my previous successes don’t make me a nervous wreck with thinking, “Help, now they’ll expect me to do a triple somersault.” It isn’t being presumptuous when I tell you that my sole anxiety comes from fear that the movie may be misunderstood, certainly not from the thought that people might expect more from me than I can give. Why should I worry about disappointing people who watch me as if I were a chorus girl who has to go one step higher each time and flaunt more and more ostrich feathers?

Signor Fellini, let’s look each other straight in the eyes. For a man who couldn’t care less you’ve made quite a stir. All that mystery about the plot so that people die of curiosity, that playing hide-and-seek with the journalists, that saying nothing even to the actors about the parts they’re playing, in short, all that secrecy…

Oh, yes? Everyone pays the price of the world he lives in; it’s the cinema that translates everything into vulgar terms. My little treasure. I’d be good enough at inventing stories if I had to and if I wanted to fall back on publicity. If I haven’t talked about my movie, it’s because I didn’t know what to say about it: I still don’t know what to say about it. It isn’t the kind of movie with a plot you can relate. When people ask me to tell them the plot. I shrug my shoulders and say. “Well, imagine that one evening you meet a friend who is in a confidential mood, and this friend disjointedly and confusedly tells you about what he does, what he dreams, about his childhood memories, his emotional entanglements, his professional doubts. You sit there listening, and at the end you have been listening to a human being. And maybe then you too feel like starting to tell him about something…” Understand? It’s a confused, chaotic snatch of talk, a confession made with abandon, at times even unbearable…

Yes, in fact there’s something Proustian about it. Proust translated into pure cinema.

Proust? Could be! I’m very ignorant… Disgraceful, eh? One healthy, vast, solid, thick-skinned ignorance. I don’t know anything about anything. And that’s not only true of books. It’s true of films, too.

I know, I know. The only movies you go to see are Federico Fellini’s. A ‘ever anyone else’s, isn’t that true?

It is so true that I have the courage to admit it. I can never get myself organized for the ritual that going to a show entails: leaving the house, getting into the car, sitting down among so many people, staying there to be tickled by collective emotions. If I do leave home to go to the movies or the theater, you can be sure that on the way there I II see something that interests me more. And then if I do see someone else’s movie and I realize that he has done something that I wanted to do… I don’t like it. Of course I’ve seen Chaplin’s films. What a fabulous artist! But for people in their forties like me, Chaplin belongs to the mythology of our lifetime: father, mother, schoolteacher, priest, Chaplin. Chaplin… I met him once in Paris. He had seen La Strada; in a low voice he complimented me, I think. He struck me as very, very small, with two tiny, tiny hands. I couldn’t understand his French, he couldn’t understand my English. I felt ill-at-ease, overawed…

Let’s forget about Chaplin, we’re here for Fellini. The main character in 8½…

You saw it? Did you like it?

Of course I liked it. But what a sad movie. All those old people, all those priests, that atmosphere of decay and death… Even the living are dead, in that movie.

Then you haven’t understood much, it isn’t a sad movie. It’s a gentle, dawn-like movie, melancholy, if anything. But melancholy is a very noble state of mind, the most nourishing and the most fertile…

If it makes you happy, let’s just say I didn’t understand much.

Little treasure, are you hungry? Are you thirsts? Do you want to lie down for a bit?

I’m not hungry. I’m not thirsty, and I don’t in the least want to lie down. Please, let me go on. As I was saying, the main character in the movie is forty-three, is a director, and is Federico Fellini. Even if you have called him Guido Anselmi…

Are you sure you don’t want anything? Coffee?

I don’t want a thing. Please. Signor Fellini, leave my tape recorder alone. If you keep on fiddling with it. you’ll break it. Why do you want to break it? By now everyone knows that your movie is autobiographical anyway, blatantly, indisputably autobiographical. Even Guido Anselmi’s hat is identical to yours. Even the way he flings his coat over his shoulders, the way he walks, smiles. Leave my tape recorder alone. Even…

But he’s a failure that director, he’s failing. Oh. baby! Do I strike you as a failure, me? Guido Anselmi is forty-three like myself, all right, hut he could equally well he forty-one or forty- seven or thirty-five like that other great director. ” At the noon of our mortal lilt* I found myself inside a gloomy wood having lost the path that leads straight ahead.” He’s a man lost in a dense dark wood…

…even the same capacity for telling lies. ‘Ton lie like you breathe.” his wife says to him. not that the resemblance shows you in a very good light. The sketch is merciless: “Hypocritical and cowardly buffoon.” “Feeble. weak-willed, and mystifying.” “Presumptuous, unsure and a cheat.” “A type who’s fond of nobody.” hid. finally, that terrible admission, “I have absolutely nothing to say but / say it just the same.”

All right, all right. What does it prove? It certainly doesn’t prove that the movie is autobiographical, in the usual sense. And even if it were? I don’t want to give the audience an interpretation based on anecdotes and autobiography: on the level of simple autobiography the movie would become merely a useless, boring, narcissistic exhibition.

Perhaps it is. A splendid, shameless, narcissistic bit of chatter.

I’m sorry, but I don’t think that’s what it is. It’s the story of a man like so many others: the story of a man who has reached the point of stagnation, a total blockage that is choking him. I hope that after the first few hundred feet the spectator forgets that Guido is a director, that is, someone who does an unusual job, and recognizes in Guido his own fears, his own doubts, his own ill manners, cowardice, ambiguity, hypocrisies: all things that are the same in a director and in a respectable lawyer and family man.

Look, Signor Fellini, the respectable lawyer might recognize himself in Guido all right, but the fact remains that Guido is Fellini. Come on, it’s like a last will and testament, that movie, a final reckoning—leaving aside the fact that making a final reckoning of one’s life at the age of forty-three seems to me to be rather too early.

Why? Better to make it early than late, when there’s no longer time to change anything. At forty-three it’s not a bit too soon to make a reckoning of one’s own life. That’s exactly why the movie did me so much good. I feel somehow liberated, now. and with a great urge to work. The movie—8½—is like my last will and testament, you’re right, and yet I don’t feel drained. On the contrary, it enriched me. If it were up to me. I’d start making another tomorrow morning. Honestly. And of course if they say. “How clever. Fellini, what talent.” it gives me a lot of pleasure. But it isn’t compliments I’m looking for with 8½. I want… I want this feeling of liberation to communicate itself to anyone who goes to see it. so that after seeing it people should feel more free, should have a presentiment of something joyful…

Good Lord Signor Fellini, don’t try to tell me you care about the people who go to see your movie. If there’s a man who couldn’t care less about his neighbor and is devoid of evangelical spirit, it’s you. Let’s drop it, for goodness’ sake, and concentrate on the important admission: the reckoning you make in 8½ is a reckoning of your own life and not of some imaginary person.

Ugh, what a little pest. What do you want me to say. So many things… of course… are true. What happens in the movie has happened to me to a certain extent. . . . There was a moment when I no longer knew what to do. could no longer remember a thing. I would work with Flajano, Pinelli, Rondi, without any conviction. I had the Saraghina episode, the one about the cardinal. But they were isolated things, floating in the void, and I could no longer remember a thing, honestly. The production team used to stand there, looking at me with imploring, suspicious eyes, and I had a strong desire to say to the producer. “Let’s drop it, let’s forget about making this movie.’’ Then it appeared to me that my bewilderment was perhaps an invitation, help from some invisible collaborator who was saying to me: “Tell the truth, tell about this.’’ And so I got the idea of making a movie about a director who wants to make a movie and can no longer remember what it is about. Yes, Guido Anselmi is only experiencing what I also partly experienced in this movie. And the conclusion, if you can call it a conclusion, is this: we must never strain ourselves trying to understand, but try to feel, with abandon. We must accept ourselves for what we are: this is what I am, and this is what I’m content to be. I want to stop building myths around myself, I want to see myself as I am: a liar, incoherent, hypocritical, cowardly… I want to have done with making problems out of life: I want to put myself in a position where I can love life, where I can love everything. I’m still talking about Guido, of course…. And after all Saint Augustine said the same thing, “Love, and do what you want.’’ Well, he didn’t put it like that exactly, but more or less…

Coming from someone who hasn’t read anything, a quote from Saint Augustine is pretty good.

It’s just that sometimes I happen to go into a bookshop and open a book, and my glance falls on a page that says something like that. Then, maybe I don’t even understand this bit my eye catches, immediately….

Liar. Tell me rather why you didn’t after all choose Laurence Olivier for the part of Federico, sorry, of Guido. He would have been perfect.

Laurence Olivier . . . an Englishman, a Knight, a very great actor. How can one? It’s too much. I needed an Italian, a friend who would humbly accept being a kind of respectful shadow, who wouldn’t put himself forward overmuch. So I took Mastroianni. I already knew him, and he was very, very good: so allusive, discreet, likable, unlikable, tender, overbearing. He’s there, and he isn’t there. Perfect.

It’s true, you become fond of the actors you use. And Giulietta? Did you lose her on the way, Giulietta?

I have a couple of movies in mind that derive from 8½ like pears from a pear tree. Giulietta will also be in the next one. For me Giulietta is a character who evokes a world where nothing is faded or tepid. I shall take up that character with fresh willingness, fresh imagination. I shall make these two movies in Italy… They keep on inviting me to go to America, offering me dizzy sums, but why should I go anywhere else? I don’t need any outside stimulus. My own land, my own countryside, the people I know are still enough to stimulate me. What would I go to New York or Bangkok for? I’m the worst traveler; when I travel, everything becomes a kaleidoscope of colors and sounds, I don’t understand a thing. All I bring back is some little item that is either useless or heartrending. And then how can one throw oneself into one’s travels if one has to keep sending back news to those who are left behind and finally has to come back oneself? I’d like to go to Egypt, maybe, or to India. But I think about it while I’m sitting down. My place is in Catholic Italy.

Yes, in your heart you are an incurable Catholic, or, at least, very much more tied to Catholicism than people think. One can tell as much from 8½; the ecclesiastical authorities have found nothing to fault in it.

Do you know any Italian who is completely lay-minded? I don’t. How could we be? We’ve had it in our blood. Catholicism. for centuries. How long? Our attempt to free ourselves of it is a necessary and most noble attempt, which we all should make. But it shows that the bruise exists, obviously. If the object against which we revolt doesn’t exist, why should we rebel against it? Guido is the victim of a medieval Catholicism that tends to humiliate man rather than to restore him to his divine stature, to his dignity. The same Catholicism has filled mental homes and hospitals and cemeteries with suicides, has monstrously brought forth an unhappy humanity, separating the spirit from the bods although they are one and the same thing. In short. Guido’s enemy is the degenerate Catholicism that Pope John is fighting in such a heroic and marvelous way. Did you like the episode of the child and Saraghina?

It is indisputably the finest in the movie, the punishment of the child especially. Those ice-cold, pitiless priests. I felt I was looking at some of Goya’s drawings again: the Inquisition, the martyrdom of the witch… So much the more pathetic in that the witch, in this case, was a child. Was it you, that child?

I never went to that kind of boarding school, but one summer l went to a Salesian convent, and it was more or less like that. You know, education based on the mortification of the body, being rapped over frost-bitten hands, how it hurts, being forced to kneel on hard com. how it hurts, that feeling of being perpetually judged by God… You think you’re alone, they keep telling you. but God n watching you. He’s always watching you. You know, to a child these are real wounds, and it’s haul to recover from them. No, I can’t cut out of my life the memory of churches, nuns, priests, voices from the pulpit, voices from the confessional, funerals… But what Italian can do without this backcloth, this choreography?

And yet, in spite of this merciless, terrifying education, you can still pray. Isn’t that so?

Certainly. Don’t you pray? Prayer is a conversation with yourself, with the most secret, most genuine, most mysterious part of yourself. And whenever you turn to it, there’s always the chance that something good will come out (if it because you’re asking help of what’s most precious, most virgin in you… God, let’s drop it. some things sound ridiculous when you talk about them. I only wanted to say that I don’t understand how anyone can fail to pray, can fail to be fascinated by the mystery. It’s so stupid to shut one’s eyes to the mystery, so inhuman, an animal attitude. The mystery of everything… the silence that surrounds you and becomes a gleam of light… Oriana! What are you making me say?

Nothing. You’re the one who’s talking. And you know whom you remind me of when you talk like this? Ingmar Bergman. It’s incredible how much you have in common, you and Bergman: you so Latin, Bergman so Nordic, you so full- blooded, Bergman so ascetic. Apart from the similarities in your movies—there are similarities, don’t you think?—you are alike in that he, too, can never do anything out of his own country, he, too. is a sinner obsessed by sin…

Bergman, yes: I’ve seen one of his movies, The Face. I liked it very very much. Bergman is the greatest author in the cinema today.

Next to Fellini? Before Fellini? Or along with Fellini?

You wretch, how should I know? How can I say? For me he’s a brother. He has what a man who speaks to others should have, the mantle of the prophet, and on his head is the tall hat with the clown’s spangles. That’s it. Bergman has both: the mantle and the spangles.

And Federico Fellini?

Hmm. Perhaps I have less mantle and more spangles.

Interesting. When I interviewed Bergman, he also tallied to me at length about you. He wanted to know heaps of things, how you live and how you talk…

And you told him the usual bullshit—God knows what you told him. My lies mixed up with yours… God! I’d like to meet him, Bergman. So far we have only written to each other. There’s a nice irresponsible producer who wanted to make a movie in three parts, with me. Bergman, and Kurosawa, that extraordinary director of The Seven Samurai. He asked me to write to Bergman, to whom incidentally I had always sent my greetings through Swedish journalists. So I wrote him: “Dear Bergman, I admire you so much and love you like a young brother. There’s this producer who wants to do this thing. In my opinion it’s a rather nutty project, but just because it’s mad, it might be worth trying.” Bergman wrote me a very beautiful letter in which he said that he would be delighted to do this thing, but in fact so far he hasn’t done anything.

Another of Bergman’s characteristics is that he doesn’t give a rap for what critics write about him, but in this respect you aren’t alike. I know that you take quite a bit of notice of certain reviews that use difficult words ending in “ism” and “asm” and are full of dialectics, ethics, aesthetics… For instance, have a look at this article.

What’s this man talking about? What’s he driving at? lie can’t have understood my movies, even though he does like them, I’m sure of it. And to put it plainly I’m sorry he likes them. I have a limited vocabulary, words like these make me feel uncomfortable. It’s true the cinema, apart from five or six comforting exceptions, gets the criticism it deserves: it’s a young, disjointed art. Everyone writes criticism in a bookish sense, never humanistically, but what do I care? I ’m not one of those who goes running to the newsagent’s to find out what such and such a critic has said—incidentally, what did Marotta say about 8½? I’m always glad to read good reviews. I know perfectly well that negative criticism can be constructive, too, but the only kind I understand is the maternal sort, all little kisses, cuddles, flattering little words…

In point of fact, in your movie, that bore who won’t give you any little hisses ends up hanged by the neck. How often have you dreamed of hanging people who don’t tell you how good you are, Signor Fellini?

Very often. Blunt criticism is to my mind very dangerous, because it kills spontaneity.

I wonder what you could have done if the cinema didn’t exist. Suppose you’d been born when the cinema didn’t exist? In you the borderline between fantasy and reality is so fluid.

What could I have done? I really don’t know. Write, no. Writing is an ascetic discipline; a writer must be surrounded by solitude, silence, I could never get used to that. I’d certainly have devoted myself to something connected with show business, or else I’d have tried to invent films. I like movies because in them you express yourself while you are living, you tell about a journey while you are making it. I am extremely lucky in this, too: I was led by the hand into the only job in which I could fulfill myself in the most joyful, immediate way…

I certainly can’t imagine a Fellini hiding himself away, a solitary thinker. We journalists have invented the deification of movie directors, but this deification suits few others as much as it does you. You always need to be on a stage, in the limelight, with an orchestra playing a little march for you.

There might be this element of vanity in me. On the other hand, plays are acted with the footlights on. Let me tell you, I’m a very shy person. Yes, I am. even though you hoot with laughter and don’t believe me; I’m really shy. And I’m glad I am because I don’t believe there can exist an artist who isn’t shy; shyness is a fount of extraordinary wealth. An artist consists of complexes.

And that other hind of wealth? That common earthly kind, a lovely bank account? By now you’re a rich man.

No, no, a thousand times no. My little treasure, how many times do I have to tell you that I am not the producer of La Dolce Vita? You know, I don’t care about money. It has its uses, that’s all. What would I do with a villa with a swimming pool? What matters is to have no debts.

Listen, Signor Fellini, the cardinal in 8½ says something chillingly true: “No one comes into the world to be happy.” Are you happy? Or at least satisfied?

Happy? Ah… yes… I’m glad to be in the world, glad to be among people. I’m interested in what happens to me. I do my work gladly, the more so since it never even seems like work to me. Satisfied? Ah… I hope I have never been completely satisfied, because that would be the end. Things have turned out very well for me. of course. But they’ve turned out the way they had to turn out.

You mean that you think it’s only right and fair that you should have had the success you’ve had? You mean that you have no doubts about the legitimacy of your success? You mean that you don’t consider with any modesty the fact that you are exalted as “the most important film phenomenon of our time”? That, in short, you consider sacred the triumph of La Dolce Vita, the Greta Garbo-like veneration that surrounds you. the fact that one newspaper advertisement is enough to bring out hordes of madmen to offer you dying grandmothers, paralytic aunts, and virtuous wives for your movies?

How can I say to what degree this is fair or unfair? I have my doubts while I am working, and the\ are the doubts of everyone who creates, who invents. Afterward, when the movie is finished. I can never make myself objective, adopt an impartial attitude. It’s as if you invited me to talk about m\ life, about a love affair, about an adventure, about a journey. How should I judge o’ No! I don’t judge, I simply say it was necessary to me. Everything that has happened to us, good or ill, has been necessary. La Dolce Vita is a movie I made years and years ago. It was harder for me to free myself of it because it was a kind of monster, it kept on growing. Whether its success is justified, I don’t know. Obviously the movie had a charge that justified so much emotion. As for the dying grandmothers and the paralytic aunts they offer me for my movies… I’m a romantic, I always like to sec life in a fantasy key, so I could say that the cinema is a siren of infinite seductive power, and that this is why they give me their dying grandmothers. Instead, I like to think that people bring them to me to help me make a movie. Take that!

What a sublime diplomat. What a heavenly hoaxer. That’s no answer. Recently, if I remember rightly, we two had a violent clash on the telephone as a result of which I shall no longer call you tu. And that time you did give me an answer, I reminded you that journalists have always treated you with esteem and affection, and you answered that journalists had always given you the treatment you deserve because you are Federico Fellini and a great artist.

Dirty liar. Rude little bitch.

Maestro, words like these will have to be deleted from the textbooks when grade school children study the life of Giuseppe Verdi, sorry, Federico Fellini.

Milan, February, 1963