It takes more than half an hour before Hirayama utters his first line. He’s a man of few words, this taciturn protagonist of Wim Wenders‘ latest and most beautiful film. In that spellbinding first half-hour, we come to understand him deeply. Yet, in that hypnotic, magnetic, enchanting first half-hour, we’ve already learned so much about him. We’ve grown fond of him. We can’t help but continue watching him, spending our time with him. For over 50 years, Wenders’ cinema has been a fixture in the realm of time, a time where seemingly nothing happens, yet everything unfolds. Life unfolds in images, revealing itself in its repetitive simplicity and primordial purity.

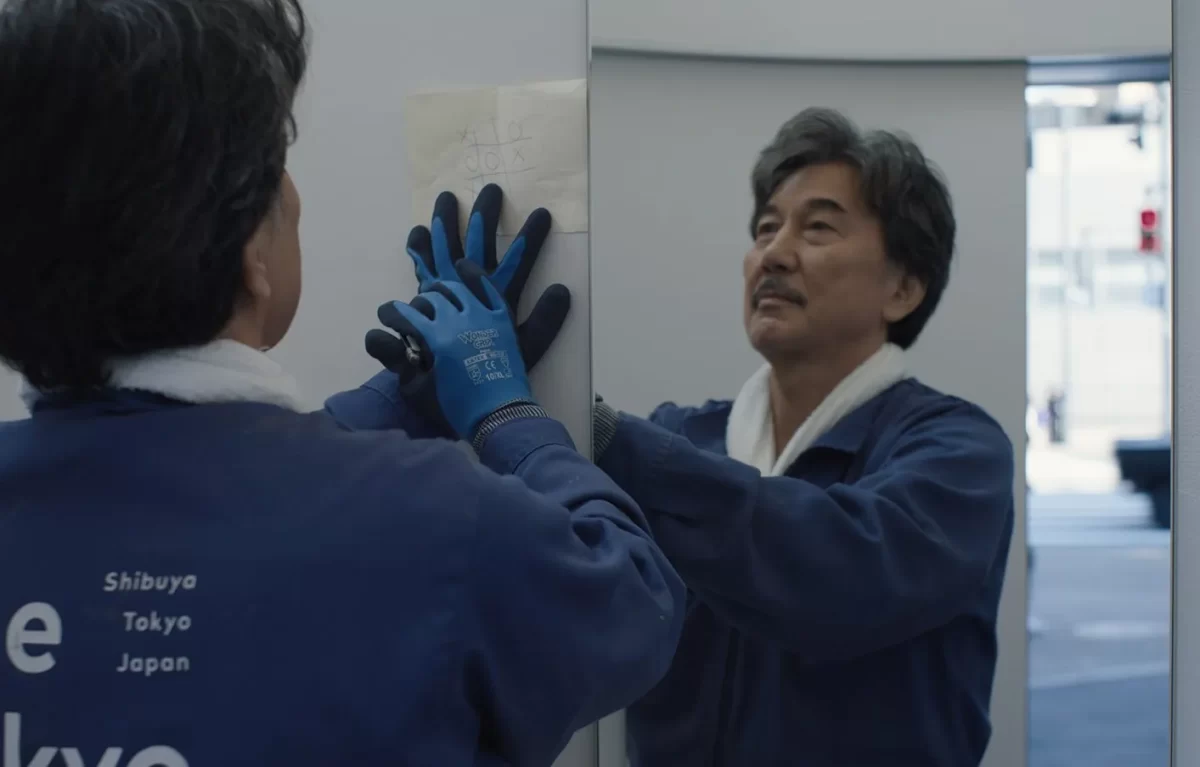

Hirayama cleans public bathrooms in Tokyo. But his story is far removed from that of the precarious workers cleaning filthy public bathrooms on the ferries crossing the English Channel in Emmanuel Carrère’s “Between Two Worlds.” This isn’t what interests Wim Wenders. Besides, Hirayama enjoys his job. He does it with passion, dedication, meticulousness, precision. Where he goes, the public bathrooms of the Japanese capital become aseptic masterpieces of contemporary architecture. Hirayama polishes, shines, cleans. He inspects toilet corners with a mirror to remove even the slightest trace of dirt. Sometimes he pulls a slip of paper from a bathroom crevice and plays tic-tac-toe with an anonymous user. Then he hops into his van, pops an audiocassette into the tape deck, and heads to the next bathroom. The songs he listens to – strictly on cassette, as Hirayama believes Spotify is a store – resonate with Wenders’ soul: from The Animals’ “The House of the Rising Sun” to Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good,” passing through Van Morrison, Patti Smith, the Velvet Underground, to “Perfect Day” by his friend Lou Reed (a nod to Reed’s roles in Wenders’ Faraway, So Close! and Palermo Shooting), which also titles the film.

Outside time, yet necessary for our time, Hirayama repeats his daily rituals: waking to the sound of a broom sweeping the street below, folding his futon, grooming his meticulously trimmed mustache, watering his plants and the small maples he tenderly cares for, then off to work. During his lunch break on a park bench, he photographs tree canopies from below with a small analog camera always in his tracksuit pocket. After his shift, he meticulously bathes in a public restroom, eats a modest meal at a market kiosk (or sometimes at a restaurant, whose owner he may quietly fancy) before returning home. Before sleep, lying on his futon, he reads William Faulkner’s The Wild Palms or Patricia Highsmith’s Cry of the Owl (from which Wenders drew inspiration for The American Friend in the 70s). Hirayama is a cultured man.

We glean that he comes from a wealthy family he chose to disconnect from. “The world,” he says, “is made of many worlds. Some connected, some not.” He severed certain ties, made a philosophical choice: to live alone, immersed in music, books, plants, and silences. A life of minimal existence, essentiality à la Ozu (Wenders’ beloved director, to whom he dedicated the unforgettable Tokyo-ga). Almost nothing happens in the film. Day after day, life repeats, punctuated by Hirayama’s nocturnal dreams. In these black-and-white photographic negatives, his dream world is filled with treetops, female faces, and breathtakingly delicate origami. Shadows, just shadows: if two overlap, do they darken, Hirayama and a stranger ponder in a chance night encounter. Or do they retain their ethereal lightness? Wenders continues to probe the nature of images and the act of seeing, of reproducing the world to visually preserve it.

With subtle movements and explorations of the state of things, always balancing between the essence of life and observation, Wenders gifts us another angel: not in the skies above Berlin, but along the streets and viaducts of Tokyo. We are left in awe of the poetry and intensity this character conveys. Such a film, capturing life’s essence without ideologies, theories, or technologies, is beyond anyone else’s reach.

Life, and nothing more. Life and the image. Is life the image? Is the image alive? For over half a century, since emerging as a key figure in the New German Cinema of the 70s, Wim Wenders has ceaselessly unveiled the world to us on screen. The world and the worlds within it. We can only thank him, once again, for such wonder.

• Perfect Days Review: Wim Wenders’ Poetic Portrayal of Tokyo’s Underbelly

1 thought on “Shadows and Echoes: The Enigmatic Symphony of Wim Wenders’ ‘Perfect Days’”

Hola, es incorrecto mirando los créditos que el libro que de P. Highsmith sea el grito del buho, el libro que lee es Once.