Official Trailer

The Books

Dune is a 1965 science-fiction novel by American author Frank Herbert, originally published as two separate serials in Analog magazine. It is the first installment of the Dune saga, and in 2003 it was cited as the world’s best-selling science fiction novel.

Dune is set in the distant future amidst a feudal interstellar society in which various noble houses control planetary fiefs. It tells the story of young Paul Atreides, whose family accepts the stewardship of the planet Arrakis. While the planet is an inhospitable and sparsely populated desert wasteland, it is the only source of melange, or “the spice,” a drug that extends life and enhances mental abilities. Melange is also necessary for space navigation, which requires a kind of multidimensional awareness and foresight that only the drug provides. As melange can only be produced on Arrakis, control of the planet is thus a coveted and dangerous undertaking. The story explores the multi-layered interactions of politics, religion, ecology, technology, and human emotion, as the factions of the empire confront each other in a struggle for the control of Arrakis and its spice.

Herbert wrote five sequels:

Dune Messiah

Children of Dune

God Emperor of Dune

Heretics of Dune

Chapterhouse: Dune.

Read more on Wikipedia

The Audiobook of Dune (1965)

Read by Scott Brick

Ultimate Guide to Dune

Source: YouTube Channel Quinn’s Ideas

Ultimate Guide To Dune (Part 1) The Introduction

Ultimate Guide To Dune (Part 2) Book One

Ultimate Guide to Dune (Part 3) Book Two

Ultimate Guide to Dune (Part 4) Children of Dune

Ultimate Guide to Dune (Part 5) God Emperor of Dune

Ultimate Guide to Dune (Part 6) Heretics of Dune

The Author: Frank Herbert

Frank Herbert on the origins of Dune (1965)

Willis E. McNelly interviews Frank Herbert on February 3, 1969 at Herbert’s house.

Frank Herbert Interview on The Dune Books

Frank Herbert speaking at UCLA 4/17/1985

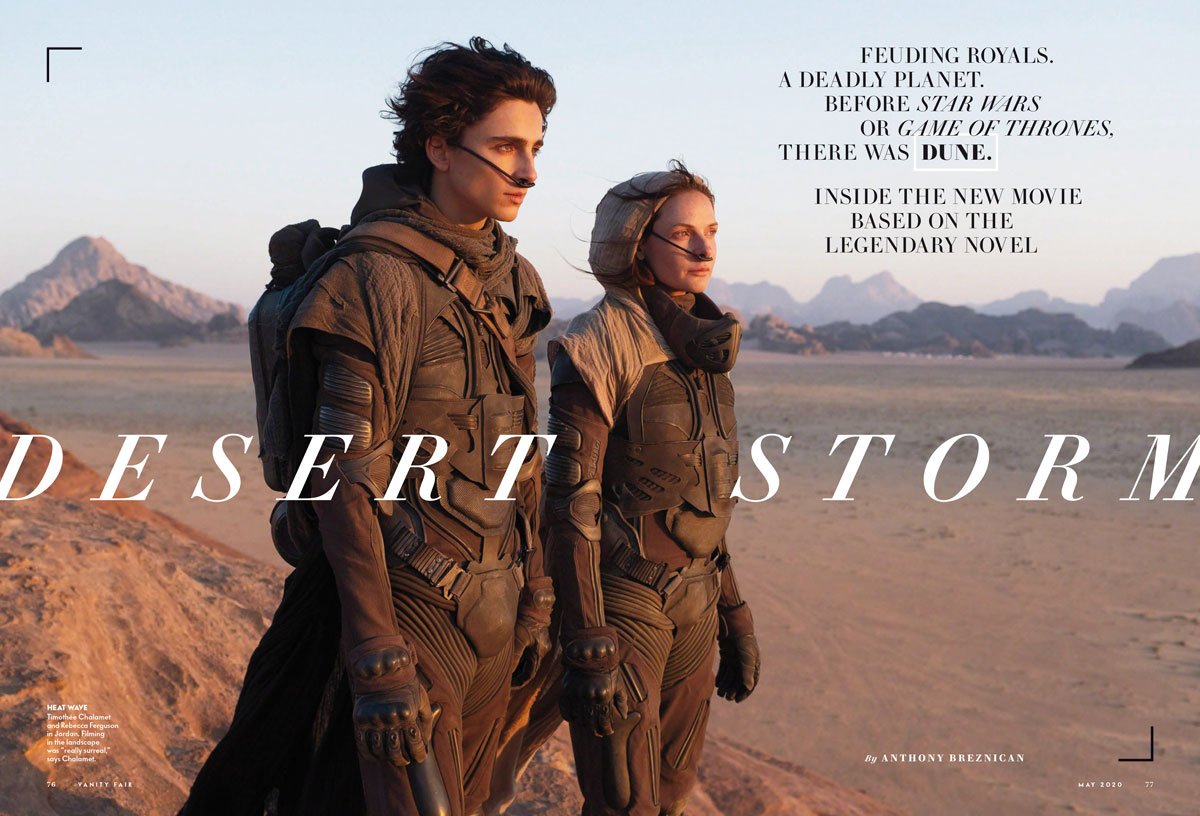

On set of Dune (2020)

What do you do when you’re given the chance to make your dreams come true? We’re talking dreams you’ve had for 30 years, dreams of a desert planet and the extraordinary characters and creatures that inhabit it. Do you shy away, leave all those images safely in your head where they’re pure and uncompromised? Or do you dive in and try to bring them to life?

If you’re Denis Villeneuve, and you’ve just been given the green light to film Frank Herbert’s Dune, you remember the book’s mantra: I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. “It’s not easy to bring the dreams of your teenage years in front of a camera,” Villeneuve admits from his editing room this July. “The teenager that I was was really a big dreamer. I had to try to please that guy. It’s all the pressure of making sure that I don’t disappoint the dream.”

If Herbert’s book isn’t quite unfilmable, it’s definitely in the same neighbourhood. Call it science-fiction’s The Lord Of The Rings: a sprawling adventure in a stunningly detailed world, and a story that’s been hugely influential in the 50 years since it was published. Ambitious filmmakers like Alejandro Jodorowsky and David Lynch tried and failed to capture its appeal: Jodorowsky blew through a large chunk of his budget in pre-production so his film was never made, while Lynch’s 1984 take was compressed to the point of incoherence. The book’s blend of complex conspiracies, elaborate social structures and philosophical musings are a lot to explain while retaining an audience’s attention, and you have to find room for the action and spectacle too.

But if you were betting, you could do worse than gamble on this take. Here’s a respected filmmaker with a proven track record in intelligent science-fiction who has adored this story for decades. And the book hasn’t aged nearly as badly as many of its contemporaries, those Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke stories where women were still housewives and ditzes. It tackles environmental threat and governmental failure, the evils of colonialism and the power of people to stand up for equality. Maybe it’s less a story about a far-future galactic empire and more a look at life on Earth. “It’s a movie that has a strong sense of adventure,” claims Villeneuve. “It’s a piece that has darkness, but it’s an epic saga with a lot of friendship, a lot of beauty at the same time, and a lot of wisdom.” At last, the time might just be right for Dune.

Frank Herbert’s Dune is nearly 600 pages long. It encompasses prophecy, mysticism, blood-feuds and metaphors for civilisation’s dependence on oil. There are gigantic sandworms about the size of the Empire State Building. There are figures called Mentats, Bene Gesserit and someone called a Kwisatz Haderach; people drink their own pee to stay alive in its deserts. There’s a lot going on.

Perhaps that’s why the previous visions failed. Alejandro Jodorowsky caught the book’s ambition, bringing in artists like H.R. Giger to design his world and hiring Salvador Dali as the Padishah Emperor at a fee of $100,000 per hour (Jodorowsky planned to keep costs down by using a mechanical double for most of his scenes). He disbursed large amounts of his budget without shooting a frame of footage, and in any case never secured nearly as much as his 14-hour epic would need. Meanwhile, David Lynch rushed the whole book into one 1984film featuring Kyle MacLachlan with glowing blue eyes and Sting in a nappy, and secured the worst reviews of his career.

“I’m a big David Lynch fan, he’s the master,” says Villeneuve of that film. “When I saw [Lynch’s] Dune I remember being excited, but his take… there are parts that I love and other elements that I am less comfortable with. So it’s like, I remember being half-satisfied. That’s why I was thinking to myself, There’s still a movie that needs to be made about that book, just a different sensibility.’”

Villeneuve had been thinking those thoughts about Dune for a long time. For years he’d dreamt of making it. But it was when he was working with composer Hans Zimmer on Blade Runner 2049 that he began to seriously discuss whether it was possible. Zimmer, another mega-fan, immediately offered his services and seems to have inspired the director to go for it. Soon after, Legendary Pictures and Warner Bros, bought into Villeneuve’s vision, which differed from the directors before him in two key ways.

First he split the story into two parts, so that he didn’t have to grapple, as Lynch did, with a rushed second act, or suggest a 14-hour running time like Jodorowsky. Crucially, it wasn’t a matter of compromising to a studio-mandated running time: Villeneuve stresses that he and screenwriter Jon Spaihts found a break point that allows this film to tell a distinct tale in its own right. The focus is now only on the early life of Timothée Chalamet’s Paul Atreides. Paul is a bright, serious young man whose parents — Oscar Isaac’s Duke Leto and Rebecca Ferguson’s Lady Jessica — are assigned to govern the desert planet of Arrakis, aka Dune. It’s a harsh world, with deep deserts plagued by enormous sandworms and a hostile populace called the Fremen. But Arrakis is also the galaxy’s only source of “spice, melange”, known as “spice”, a valuable substance that extends life, sparks prophetic trances and — most important of all — enables the galaxy’s Guild of Navigators to travel faster-than-light between the stars.

Like the multi-purpose spice, the planet is both a potential goldmine and a powder keg. Duke Leto knows his new assignment is probably a trap. The outgoing governors and his sworn enemies, the Harkonnens, undoubtedly hope to turn the assignment against him. And yet, under Imperial orders, he has no choice. He must trust in his loyal retainers and a hoped-for alliance with the Fremen to keep himself and his family safe, and keep the spice flowing. The stakes are literally galactic.

Against that enormous canvas, Villeneuve’s second key decision was to make Dune feel as real as it did to him when he first read the book. So the director insisted on desert locations and vast practical sets. The production’s location shooting was in Jordan’s famed Wadi Rum and the deep dunes of Abu Dhabi. About the only things added in post were the sandworms and spaceships — and not even all of the latter, because under Villeneuve’s regular production designer Patrice Vermette, the crew built full-scale models of the planet’s favourite air transport, the ornithopter. And then there were the humans.

Villeneuve had to assemble a cast so charismatic that you’d actually listen when they explained this complicated society, and actually care when fighting erupts (spoiler: it totally will). That, however, came easy, thanks to his reputation and that of the book. Chalamet had set up a Google alert for the movie as soon as he heard it was in development, and flew to Cannes to meet Villeneuve when the director was on the jury there. “I can’t pretend that I was sitting there evaluating whether I wanted to do this or not,” says Chalamet. “It’s very obvious, just the opportunity to work with Denis. I’m a huge fan.”

For Villeneuve, Chalamet was the only person who could play Paul Atreides, the boy groomed for leadership who’s plagued by prophetic dreams of a strange desert planet even before he arrives there. He has what Villeneuve describes as an “old soul” combined with the ability to appear many years younger than 24. “He has an insane charisma,” says Villeneuve. “Timothee has been gifted by the gods of cinema.” Then Villeneuve went looking for his Lady Jessica, and found Rebecca Ferguson. “I didn’t want Lady Jessica to be an expensive extra,” says Villeneuve of a character who has been slightly sidelined in some versions but is important here. “Something I deeply love in the book is that there was a strong balance between the masculine power and feminine power.”

Isaac knew both the book and Villeneuve, and had reached out as soon as he knew the film was happening, for any role going. “So you like Dune. Iiiinteresting,” the director replied teasingly. Later the call came through asking Isaac to play Duke Leto. “When I read it again, Leto is the character that popped out to me,” says Isaac now. “Not only from the description physically, but also the conflict between wanting to protect his family, his people, but being forced into an impossible situation that is perilous and yet hoping that he can gain advantage in it.”

That’s how it went across almost the entire cast. Brolin, who plays Atreides weapons master and (according to Villeneuve) “warrior poet” Gurney Halleck, didn’t even read the script before committing to reteam with his Sicario director (“I think I pretended to read it”). Jason Momoa, as Atreides fighter and spy Duncan Idaho, signed up almost as quickly. “I was literally on top of a mountain, no shit, and he’s one of my top three favourite [directors] of all time. So I snowboarded down the mountain and got my ass back to the hotel room. Got on a Skype call with him, said, Til do it,’ right away. It’s like winning the lottery when you get a job like that.”

Leading the Fremen is Javier Bardem’s Stilgar, with Zendaya as a younger Fremen, Chani. “She’s tough and she’s very straight up,” says Zendaya of her role, a relatively small one that could lead to bigger things if there’s a sequel. “She’s already sizing Paul up and not quick to trust.” Balanced between these groups is Sharon Duncan-Brewster’s Kynes, an Imperial planetologist on Arrakis. In the book, Kynes was (yet another) white man, but Villeneuve wanted more women because “we are in 2020. I cannot do Lawrence Of Arabia!” Kynes was an obvious character to swap. As Duncan-Brewster says, “Personally, I didn’t see how Kynes being a woman would affect any aspect of the plot. I believe Frank Herbert wouldn’t have minded.” Her quiet, reserved scientist is one of the most important figures in the book, someone with close ties to the Fremen despite her Imperial job title.

Another touch of spice comes from Charlotte Rampling as the Gaius Helen Mohiam, Reverend Mother of the Bene Gesserit — an order of witches/ prophetesses/nuns/concubines that trained Lady Jessica, and a group with their own mysterious priorities. Rampling was in line to play Lady Jessica for Jodorowsky 45 years ago, so maybe she was always meant for Dune. Perhaps Villeneuve’s dreams were as prophetic as those of Paul Atreides.

As casts go, it’s an embarrassment of riches; the biggest challenge for about half the team was trying not to trip out at the other half. One of the first things shot in Budapest was a meeting of the Atreides, Fremen and intermediaries in the Great Hall, during which almost all the stars were starstruck.

“It’s just this amazing line-up,” remembers Momoa. “You’ve got Brolin, Oscar Isaac, Timothee. And in walks Javier Bardem and I have never seen anyone that cool in all my life. That’s why he wins fuckin’ Oscars, bro. He walked in like he’s a silverback and just stares us all down.” Bardem, told this, laughs and claims that he was very nervous but that “if Jason Momoa calls you a gorilla that’s a big compliment because he’s King Kong.”

Villeneuve is proud of his cast. “I made no compromise,” he says. That would become a theme. When it came to the scale of the shoot, his ambitions were equally enormous.

It’s June 2019 and Empire is at Origo Studios, a few miles outside Budapest. We’re also a few million light-years away from Earth, standing in the Atreides residence in Arrakeen, their capital on Arrakis. It’s meant as a Brutalist structure, a sandy-coloured concrete carbuncle, built by the Harkonnens as a symbol of power and dominance. Its hallways stretch for 100 metres, walls reaching high overhead so that there’s no need for green-screen extension in most shots. The place has the air of some monumental tomb despite the (specially printed) acres of Persian- style carpet underfoot. Bas-relief murals show sandworms at play; huge, bronze doors swing on central pivots. “And this is just a corridor!” says Vermette. “Not even the Great Hall. We’re having fun.” It’s all so vast, Rebecca Ferguson has been getting lost. “Every bloody day,” she says. “Like, ‘Am I on the wrong stage? Hellooooo?”’

For Empire’s visit, however, she is on the correct stage, for a scene where the Atreides family say goodbye to their household staff on their oceanic home planet of Caladan before moving to Arrakis. Chalamet, Ferguson and Isaac have formed a sort of receiving line for their old retainers, with Duke Leto putting a comforting hand on his lady’s neck as she bids farewell to the last of them. Packing cases lie around with their ancestral treasures spilling out, and it’s all very moving. Between takes, Chalamet paces restlessly nearby until it’s time to go again, the weight of the world — or at least, the film — on his shoulders.

The Arrakeen spaceport outside is bigger again, lined with palm trees that will, at some point, be set ablaze. There’s a full-size ornithopter parked at one end and a ramp down into the residence at the other. But size is not the only thing this production has going for it. In the prop department, the detail holds up to near-microscopic levels. The ‘Gom Jabbar’, a tiny, poisoned needle with which the Reverend Mother tests Paul, is finely etched along its length in minute swirls and circles, a thing of beauty as well as horror.

This level of world-building came as standard For Stellan Skarsgård’s Baron Harkonnen the hair and make-up department had to provide a grotesque fat-suit that would absolutely not be comical. Skarsgård is someone Villeneuve had admired since Breaking The Waves, and he was cast for one simple reason: the director finds him scary — and he needed to stay scary. Costumes, meanwhile, had to provide the scale of an epic with the detail of a tiny chamber piece, manufacturing the high style of the nobles (based partly on cavalry uniforms) and the Fremen ‘still suits’. These are Dune’s signature look — desert wear, designed to protect every drop of moisture in the body and to recycle all waste water back into potable supplies. “A real, functioning distillery,” as costume designer Jacqueline West puts it. And it had to be wearable in a real desert.

Even though the Wadi Rum has been home to hundreds of productions, from The Martian to Lawrence Of Arabia, it still struck most of the cast and crew as an alien, magical place. For Isaac, the desert shoot was a sort of homecoming after Star Wars: The Rise Of Skywalker. “the same desert,” he notes. “But it’s kind of incredible how two different filmmakers can take a place and give it a completely distinct feel.”

On off-days there were jeep rides or “camels cruising by”, as Momoa puts it — but it was the vast, empty space that made Arrakis feel real and acting almost unnecessary. You can believe a sandworm might pursue you across this environment. “That part of the Wadi Rum is so awe-inspiring, you might as well be getting chased by that cliff in the background,” said Chalamet. “It wasn’t a green-screen or anything. That’s one of the most thrilling parts of the book and the movie. We had the sketches. That was a lesson for me. On a Call Me By Your Name or Beautiful Boy it can be counterintuitive to see the storyboards because then maybe you limit yourself based on a camera angle or whatever. It’s the opposite [here] because, for a sequence with the sandworm chasing you, I could never imagine that.”

Filming on such a scale takes time. At the top of the call sheet for nearly six months, Chalamet got to grips with his first blockbuster lead. This is a far bigger film than anything he’s played the lead in before — but then, that fits Paul’s story pretty well. He is “on a hero’s journey that he didn’t sign up for”, as Chalamet puts it, something far bigger than his experience prepared him to face. How else could you approach that except by jumping in feet-first?

Is the world ready for Dune? For all its action and spectacle, a science- fiction film this big and this serious- minded is a risk. The last Dune was a famous flop and Villeneuve’s previous film, Blade Runner 2049, underperformed at the box office despite rave reviews. Might Dune be simply too dense for modem audiences? It’s clearly a concern for Villeneuve and his team: summer 2020 saw pick-up shooting take place to clarify plot points, making sure that the audience would understand what’s going on at all times. Yet the book also has themes that resonate today, ideas that could strike a big chord with audiences looking to make sense of the world and all the challenges we’re currently facing.

“The book, for me, is about prescience,” says Villeneuve. “A character that can see the future. I feel that Herbert himself had a pretty good view of the future, people exploiting natural resources with brutality and other people fighting for the sake of nature.” He wants young people, in particular, to discover this story through the film as he once discovered the book, and to fall in love with Herbert’s “beautiful ecosystems and unique relationship with nature”.

For Isaac, the challenge is not Dune’s earnestness, but merely a question of balancing the complexities of the book with the needs of a populist piece of cinema. “It’s about the destiny of a people, and the different way that cultures have dominated other ones. How do a people respond when it’s at the tipping point, when enough is enough, when they’re exploited? All those things are things we’re seeing around the world right now.”

Or as Brolin says, simply, “People are not as dumb as you think they are.”

Whether or not this makes spice-coffers full of money, Villeneuve claims he’s happy to have come this far — and his attitude on set is laid-back enough that you believe him. On Sicario, Brolin remembers inviting Villeneuve over for margaritas on a Friday night, only for the director to sit, disconsolate, feet dangling in the swimming pool, staring into the depths. “He was like a depressive, always totally saturated with the problems of, ‘How do I make this the best thing?’ On this, he was more ebullient. Knowing Denis so well, to be able to see manifested what he’s been talking about for so long was such a delight. I’m glad I’m a part of this childhood dream come true.”

If this does work for mass audiences, Villeneuve hopes to return to tell the rest of Paul Atreides’ story. Whereas this film is about a boy losing his innocence and adapting to a new culture, the sequel would see him at “full potential” as a leader, because the threat posed by the Harkonnens, and the dangers of the sands of Dune, will not be entirely defused here. But if it all goes wrong, at least he got to visit Arrakis once. Herbert said that, “There is no real ending. It’s just the place you stop the story.” If the story closes here, at least Villeneuve has made his teenage self happy. Maybe sometimes you don’t need to be careful what you wish for. Sometimes you should throw caution to the desert winds.

Empire, October 2020.pdf

Desert Storm

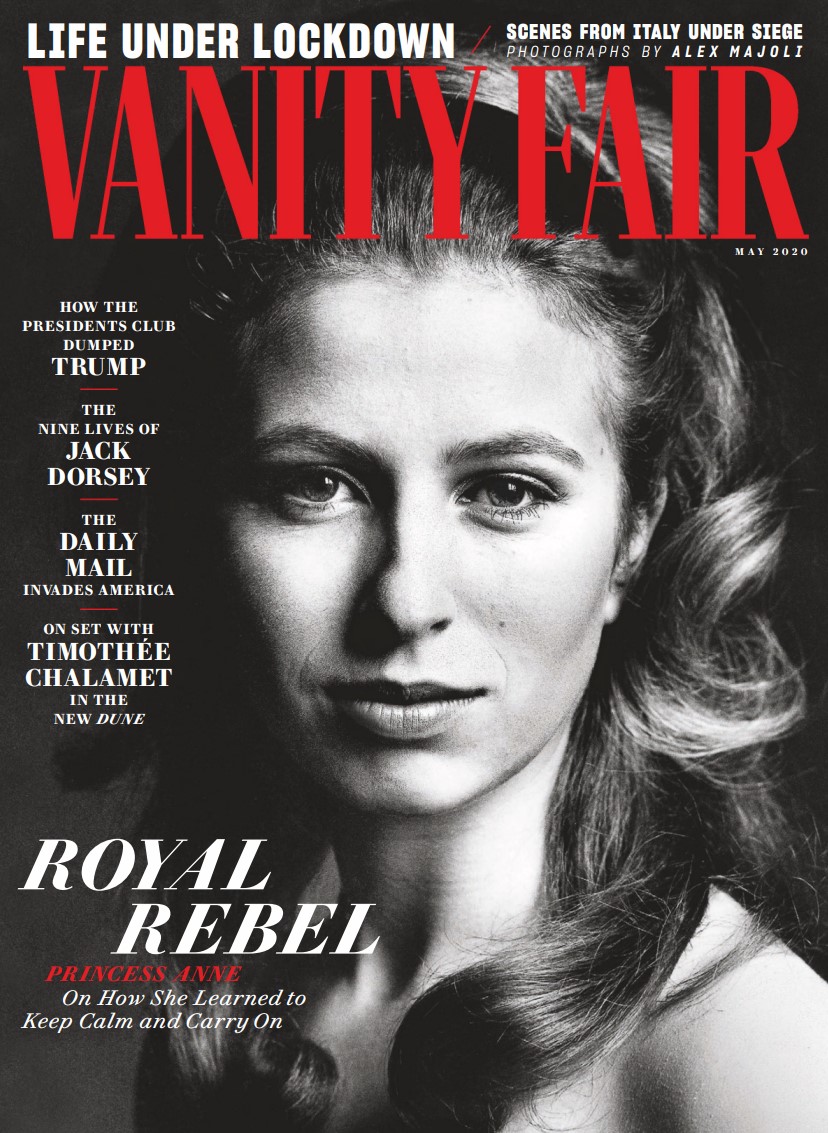

Vanity Fair UK, May 2020.pdf

Discussions

https://www.reddit.com/r/dune/