by David Hutchison

It could be run as a very simple news headline: “Doug Trumbull Directs, Again!” But this really is big news. Trumbull, who has been typecast for some years now as Hollywood’s top special-effects supervisor, is returning to the director’s chair with a project that has been brewing in the back of his mind for some time.

The film is entitled Brainstorm, and is officially described as “a contemporary action-drama set, against the high technology environment of modern research and development.” Trumbull, best known for his consciousness-dazzling effects in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the visual effects delights of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Paramount’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture, is leaving star fields and spaceships behind to delve into the inner space of the human mind in his new film, Brainstorm.

This M.G.M. feature will be Trumbull’s second directing effort. In 1971 he demonstrated that quality science fiction could be produced on a low budget and a short schedule—given people who knew what they were doing and cared about what they were doing. In contrast to years of cheap looking “Sci-Fi” exploitation films, Trumbull’s Silent Running has achieved a special and well deserved niche in the annals of SF moviemaking.

Additionally, Trumbull is accepting the second chair of Supervisor of Special Visual Effects on Brainstorm through the extensive facilities of his new company, Entertainment Effects Group (EEG), in which he is partnered wtih Brainstorm cinematographer and associate producer, Richard Yuricich.

In order for Starlog to get a first hand preview of Brainstorm and director Trumbull’s dual role, I traveled to Los Angeles to visit Trumbull’s effects company, EEG, and then later to locations in North Carolina— where more than half of the picture is being shot.

When I arrived at EEG in August, the 20,000 square foot facility was largely devoted to turning out high calibre effects for Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. The building looks ordinary enough from the outside—a long, low-profile California warehouse that looks identical to the hundreds of other California-style industrial buildings that surround Los Angeles. But the magic starts the moment you walk through the door. Instantly, I felt that I had shrunk to half size!

EEG is equipped almost exclusively for super-format photography. Everything is twice as big to accommodate the 65mm camera stock and 70mm release print stock. A film can is twice its normal diameter, editing benches, rewinds, synchronizer blocks—are all twice “normal” size. I felt that I had somehow shrunk to half my normal size, like some science-fiction Alice in Wonderland.

Ever since Close Encounters, I am told, Doug Trumbull has been building an extensive inventory of 70mm cameras and associated equipment. Doug is a firm believer in the 70mm super format, not only just for the production of special-effects shots in feature film production, but for use in Showscan, his special high speed 70mm process.

Showscan

I first wrote about Showscan for Future Life #1 and that article has been reprinted in Starlog’s Photo Guide Book Special Effects, Volume III. (It describes the process in detail and those interested are urged to refer to it for a full description.) Essentially, Showscan is a large screen 70mm process. Showscan films are photographed and projected at 60 frames per second, which is 2½ times the standard rate of 24 frames per second. This increased frame rate coupled with a much brighter image than usual and a unique multichannel sound system creates a super-heightened sense of reality for the viewer. A typical large theater screen today may measure 19 by 35 feet. The Showscan screen will typically measure 49 by 108 feet.

“Brainstorm,” Trumbull explains, “was developed and conceived for the Showscan process. But it has been impossible at this time to get M.G.M. or any other major studio interested in the process. The studios think that it is virtually impossible to get the theater owners to change over to any kind of new equipment to project a film. Showscan is now being developed as an independent enterprise. We will produce our own films, design, build and construct our own theaters. It will exist as a whole, new separate industry, apart from feature films—sort of an experience theater.”

Trumbull predicts that “within a year we will have some Showscan theaters up and operating (either in Manhattan or Los Angeles); we think they will be very successful in generating revenue… perhaps the movie industry will reconsider Showscan at that time.”

As we walk onto one of the miniature stages a model of the futuristic New York City skyline is canted at an odd angle in preparation for filming. Again, everything is being shot, here, in 65mm. “The plan is,” Doug later explains, “for our 65mm effects negative to be used to make the 70mm release prints… we hope. On CE3K our effects material shot in 65mm was reduced to 35mm, intercut with the rest of the negative and then enlarged to 70mm for the release prints. We hope to be able to go directly from our original 65mm negative for the effects in Blade Runner.

“The audiences today don’t know what real 70mm looks like. All of the 70mm prints in circulation are blow-ups from 35mm. Audiences get the increased value of six-track magnetic sound with the 70mm print, but they are not getting a high fidelity 70mm image. Look at 2001. If you can find a good 70mm print of the original 65mm negative, the image quality is fantastic. But I don’t think anybody has struck a 70mm print of the original negative for years. Audiences keep getting sold 70mm, but what they are getting is a blow-up from 35.

“Brainstorm, which was originally supposed to be in Showscan, is being shot in 35mm anamorphic and 65mm. It is the first time a film has been shot using both Panavi- sion and Super-Panavision formats. Special prints will be made, which will allow the film to be projected normally. Special masks will be built into the prints so that the picture will change from a 1.66 aspect ratio to 2.35. Dramatically, it [the increase to a larger image] is part of the story. A special series of point-of- view shots, flashbacks and the special effects are being shot in 65mm. Everything else is being shot in 35mm. I think it will be very interesting in the theater—the format changes are locked very tightly into the dramatic structure of the film.”

The tour through EEG continues past offices, stages, screening room, machine shop, editorial facilities, optical printers, animation cameras, the matte painting department and one of the “stars” of the EEG plant, Compsey. (Compsey is a super sophisticated computerized camera developed by Richard Hollander and Evans Wetmore and needs an article of its own.)

In the matte painting department Matthew Yuricich is finishing off a painting of a vertiginous view down the side of a Metropolis-like skyscraper. The painting is for Blade Runner. For a matte painting, the style seems very loose, soft, lacking contrast and too “painterly.” Matthew just smiles at me when I remark how unlike the sharp, clear edges of the model city in the next room his matte painting is. “Look at one of the test clips on the light box,” he invites. Several strips of super-size 65mm film are laid out on a light box next to Matthew’s easel. I squint through a loupe to get a magnified view of the matte painting test. I am amazed. The film clip looks nothing like the painting. What was soft, fuzzy and lacking in contrast is suddenly sharp, clear and rich in contrast and color. Matthew explains that he is painting in “false” color for interpositive stock, not standard camera stock. It’s possible to save a generation by using interpositive stock, but it means the artist cannot paint realistically. I look again at the soft, fuzzy gray, almost pastel rendering and then back at the film clip with its sharply etched rich tones. Amazing.

Trumbull sums up the secret to EEG’s future as a facility housing the finest effects technology and personnel available. “Our major advantage is having a group of people who can interpret visual concepts on an artistic level, and know precisely the technology to bring those concepts to the screen.”

On Location

In mid-October I rejoined Doug Trumbull’s crew in North Carolina for Brainstorm’s location sequences. Why North Carolina? I asked Trumbull. “Well, we were originally thinking of shooting in Boston, but what I really wanted was a location in the country with lots of trees, but still where there was a lot of high-powered research going on. I was told that Research Triangle Park in North Carolina was ‘where it’s at.’ ”

The Research Triangle Park does indeed fit the bill. One of the locations selected is the Burroughs Wellcome Co. research facility and executive headquarters. The Burroughs Wellcome building is a futuristic assemblage of hexagons built somewhat like an A-frame vertically, but roughly in the shape of an “S” when seen from above. All the walls slope at 22½°—even the flagpole in front of the building leans at 22½°! It was designed by Paul Rudolf of New York and serves as the setting for the research and development branch of a large American corporation.

Oscar-winner Cliff Robertson is on hand to play the corporation’s chief exec, while Christopher Walken, winner of the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his role in The Deer Hunter, toplines as a young scientist at work on a startling invention. Natalie Wood stars as Walken’s wife, who is an industrial design specialist with her husband’s firm. Another Oscar winner Louise Fletcher, is Walken’s research partner, a scholarly and determined scientific pioneer.

Burroughs Wellcome, one of the world’s- largest pharmaceutical firms, is the principal location, but the company is also shooting sequences on the Duke University campus, including the hybaric chambers of the Medical Center, the University Chapel and the Duke Gardens. Other locations include a futuristic “solar house” in Chapel Hill, privately owned by two lawyers, a country club in nearby Southern Pines, and Kitty Hawk for the film’s finale—which of course is the location of the Wright Brothers Memorial, site of man’s first successful airplane flight.

My first day on location with the Brainstorm company is spent at the Duke University Chapel. The unit publicist, Don Levy, explains as we drive in from our accomdations in Research Triangle Park to watch for small white signs with three red “X”s painted on them. These signs guide the production company members to the right location for each day’s shoot. And, since they don’t say “M.G.M.” or “Brainstorm” in large letters, they will not serve as guides to fans and onlookers. Clever.

Unfortunately, this is a big production and hard to hide. As we turn through the main gate of the University I can spot half a dozen gleaming blue tractor trailers with enormous M.G.M. lions painted on them. The famous Leo trademark is visible from at least half a mile away and I begin to wonder if perhaps the production manager is placing too much faith in those little white signs with the three red “X”s.

Towering above the Brainstorm production trucks is the 210 foot tower of the University Chapel. Aldous Huxley was once quoted as saying that “the Duke University Chapel is the best essay in neo-gothic architecture in the New World.” I believe him. The cornerstone of this enormous chapel was laid in about 1930. Its 210 foot high tower is balanced by the main part of the church which is 320 feet long. There are over 900 human figures in the stain glass windows. The chapel has two entirely separate pipe organs and a 59 or 61 note carillon in the tower, which was cast by the same firm in England that did the bells for the National Cathedral in Washington, among others.

As we enter the chapel, Doug Trumbull (looking years younger than when I last saw him during the production of Star Trek), wearing a Duke University windbreaker, is setting up a shot that will include the entire length of the chapel. Down in front the Duke University choir is being rehearsed by choirmaster Ben Smith. A few hundred extras are seated in pews near a coffin which is surrounded by flowers. “Who is supposed to be in the coffin?” I ask the publicist, whipping out a pad and pencil. “Uh, I can’t tell you,” is the hesitant reply. (It is a phrase I am destined to hear repeated many times over the next few days.) “You see, Doug needs to keep the details of the plot secret for a few more months. .. we don’t want to get ripped off by a TV movie of the week and there are some plot surprises that should stay surprises….” Well, OK, I can work around that.

As I move towards the front of the chapel, the choir begins to sing the standard Doxology (Old 100), but very slowly. The sound is magnificent. The reverb time in the chapel is about 5½ seconds and the acoustics of the chapel have the odd quality of minimizing quiet sounds and amplifying loud ones. The sound of the 150 voice choir seems to flow in slow waves into every nook and niche.

A smiling gentleman with a trim white beard and just a touch of a New England accent comes over to chat. He is William Crofut, an old friend of Doug Trumbull who is acting as music consultant for the picture. He gestures back at the choir, “Aren’t they wonderful?” he asks. “We had planned to use a pre-recorded performance of a 700 voice choir, but the 150 voices of the Duke choir sound so good that I threw out the 700 voice version.”

Doug Trumbull waves Bill Crofut over, as everything is finally ready for this first complicated take of the morning. The stars, Christopher Walken, Cliff Robertson and Natalie Wood, come onto the set and take their positions in the first pew. Keeping out of camera range, I make my way to the rear of the chapel bumping into Louise Fletcher, who will not be needed for shooting until the afternoon. I introduce myself and ask her about her working relationship with Trumbull.

“He’s wonderful,” is her immediate reaction. “He’s allowed us the rare luxury of three weeks of rehearsal before shooting. We’ve all had time to get to know each other and the script. It’s helped enormously. If I had my way, all directors would be required to allow three weeks of rehearsal.

“The nice thing about Doug is that when he makes a suggestion, it always makes sense. When he makes a criticism, it is always valid. He is very enthusiastic…a boyish enthusiasm. He is not afraid to show it when he is pleased.”

Louise excuses herself and I settle down to watch Trumbull at work for the rest of the morning. It is a very complicated set-up inside a cavernous chapel, with extras, props, lights and crew everywhere. Incredibly, Trumbull remains calm, genial and soft spoken; not once during the three days I was with the company did Trumbull project anything other than quiet confidence, an eager enthusiasm for what he was doing and great respect for every member of his company… down to the last go-fer. Trumbull does not remain aloof from his company, he sits with his crew at meals and his incredible enthusiasm infects every member of the company.

At lunch, I find myself seated next to him. Long tables have been laid out on the lawn in front of the chapel. Several starstruck students and movie fans are craning for a glimpse of Natalie Wood or Chris Walken… and Doug Trumbull.

I pass on to Doug Louise Fletcher’s comments about the luxury of a long rehearsal period. Doug nods, “I can’t believe the horror stories I hear from the actors about their experiences with some other directors. They tell me that some directors just push them out in front of the cameras with instructions to ‘act.’ I can’t work that way and I don’t see how anybody else can. It just seems to me that if I have an idea in my head about how a certain scene should be played, then I should tell them. Then they should tell me what they think. .. it’s a lot of give and take. This sort of thing is particularly important when you are dealing with a film about people and personal relationships. The characters in this film are scientists, but they are people first. Scientists have been portrayed as weirdos in SF films for so long. . . I think the scientific community will like what we are doing and I think the movie-going public will enjoy it more.

“The cast has responded very well. I really enjoyed working with actors. The movie industry has typecast me as a techno-freak, so it’s been a long haul for the movie industry to accept me as something else.”

Doug explains how the film was rehearsed. “We began with a solid week of reading rehearsals. This was about a month prior to photography. With the actors suggestions we were able iron out a lot of bugs in the script, rework it and polish it. Then when we got here, we had another two solid weeks of rehearsals—going through every scene, every line, every word… trying to really get a feeling for what we are trying to do. It’s worked out fabulously.

“So now, when we come onto set, there’s no messing around wasting the crew’s time while we figure out how to play something. The actors are confident and relaxed, because they know exactly what has to be done and how it all fits together.

“Working this way, we have been able to fine-tune the characters in terms of their relationships with each other; they know who they are and where they came from, how they feel about each other and themselves. I think the finished film will be a rare blend of really good performances in what might be a quality dramatic film such as Ordinary People, combined with the special effects, high-tech aura of an SF film. Those two things don’t come together very often.

“I want this film to have a very broad appeal outside of the SF community. I would like this film to attract people who normally don’t go to movies. Statistically, only a very small percentage of the population goes to movies regularly.”

An interesting Afternoon

Lunch is breaking up and Doug and I walk back to the chapel for the rest of the afternoon’s scenes. Louise Fletcher has a scene coming up with the university chaplain, Reverend Richard Young. Doug is pleased with the way the Duke University chaplain is working out as an actor and is inclined to enlarge his role a little. He wants to shoot a sequence with Louise and the Reverend at the top of the 210-foot bell tower. In the front of the church is a tiny round Otis elevator just large enough to squeeze in four very close friends for the ride to the top. Doug intends to transport to the top of the tower, himself, two actors, skeleton crew, sound man, a 65mm Super Panavision camera and camera personnel. It’s going to be an interesting afternoon.

Obviously, for this scene there is no room for spectators so the unit publicist takes me and another journalist on a short drive south to Chapel Hill to look over the “solar” house that was used for Natalie Wood and Christopher Walken’s residence.

As we drive along the four lane highway to Chapel Hill, home of the University of North Carolina (from which Louise Fletcher received a degree in drama), I am amazed at the super-modern towers and pyramids of glass and steel that rise out of the trees every few miles. Apparently this area of North Carolina is famous for its modern architecture and forest settings. A few miles to the east, the zoning regulations for the Research Triangle Park are so stringent that the building can occupy no more than 15% of a company’s land area.

The “solar” house is just that—a private home owned by two lawyers that has been rented by the production company. Apparently it is one of several in the area. Minor modifications have been made to the home and the backyard has been “dressed” with additional solar panels and small backyard observatory. Inside there is a working NASA rocket engine, just sitting as a decoration next to the indoor pool. Production designer, John C. Vallone, commented to me later about the engine.

“Doug can get the darndest things to work for him. My first reaction was that with all the solar panels and the observatory, that perhaps the rocket motor was going just a bit far. But Doug gets it to work for him by making a bit out of it for the actors. There is a scene in the film in which Natalie is showing the house to prospective buyers. They pass the rocket engine and the prospective buyers point to it somewhat incredulously, saying, ‘What is that? Well, Natalie just shrugs it off with a look that says ‘Don’t ask me…it’s my husband’s!’ It’s a nice little moment that works. If the engine were just a prop lying in the background it would draw attention to itself and be a distraction, but Doug makes something out of it and it works… it’s accepted.”

Back on the Duke campus it’s getting dark and the crew is beginning to wrap for the day. The dinner wagon is open though, and I help myself to a plate of spaghetti and find an empty place across a table from Bill Crofut. I want to know what kind of musical advice he is giving Doug that does not entail writing a score.

“Well, there was a scene in which several people are entertaining themselves playing chamber music. The scene required Natalie Wood to be at the piano playing. She has to stop playing in the middle of the piece for about 35 or 40 seconds, exchange some dialog and then go back to playing, all on time and without missing a beat. Well, I suggested, and we used, the Schubert ‘Trout’ Quintet. Luckily, Natalie knows how to play the piano, so we didn’t have to fake the shots of her hands on the keys. The music is pre-recorded so she does not have the added anxiety of having to be note perfect as well as play a scene, but her musical ability makes the scene much easier and more interesting to shoot.

“Though we’ve been friends for years, this is the first time I’ve worked with Doug professionally. This is also the first project in which I get not only respect but appreciation for the work I do; but that’s Doug for you. He’s very aware of what everyone is doing— he knows and he cares. Doug has a knack of making you feel very special. Now, the last thing in the world that I’d call him is a god, he’s a fallible person just like the rest of us and he can lose his temper just like anybody else.. .but not terribly often.”

Last to arrive for supper is Trumbull, who pulls up a chair next to Bill Crofut and me. It’s been a long hard day in a difficult location, but Trumbull is bubbling with energy.

“We just shot this scene on the roof of the chapel with Louise and the Reverend Young. Great scene. Louise is a professional but the chaplain is not and he was magnificent! He got to say a lot of things in this scene, that I think he would like to say to everybody. He says to Louise, ‘Is work really enough for you? Don’t you think maybe there’s something more to life? Are you just going to work your butt off all your life and not have any relationships? There is more to life, you know….’ She answers saying how she’s worked all her life, but is still disappointed. …

“Its amazing how when people are vulnerable they will confide in a minister or some sort of third party. They say things that they would never say to their lover, spouse or best friend… and yet, it would mean the most to those people. Yet, they confide in a relative stranger.” An interesting, and accurate, observation.

The conversation shifts to tomorrow’s schedule at the Duke Memorial Gardens. All of tomorrow’s sequences will be shot in 65mm and many with a super-wide angle lens that has been specially borrowed for the production.

By the time you read this the nine-week principal photography schedule will be over. There are a few weeks of second unit work and then many months back at EEG, creating and assembling the special-effects material. There is no definite release date for the film at this time, though looking ahead it is thought that the film might be ready by late summer. Trumbull will finish the film as soon as possible in order to get on with his next project, Millennium (to be shot entirely in 65mm), but you can bet he won’t let Brainstorm out of his hands until he is happy with it. Such is his relationship with M.G.M. and executive producer, Joel L. Freedman.

Brainstorm is from an original script by Bruce Rubin, Phillip Messina and Robert Stitzel. John C. Vallone is production designer with Tom Pedigo, set decorator. Costumes by Academy award-winning designer Don- feld; Bill O’Brien, art director.

Longtime associate of Doug Trumbull, Richard Yuricich is the director of cinematography and associate producer. Property master is Jack Ackerman (who as a young boy worked on The Wizard of Oz) and Art Rochester is the sound mixer. He has come up with some new recording techniques and is experimenting with digital sound for Brainstorm, so we may expect an aural as well as a visual feast.

One last item—like most movie locations, there were the usual folding chairs for the stars and one for the director. They were nice chairs and Doug’s had his name neatly lettered on the back and front. I never saw him sitting in it, though.

Starlog, Number 55, February 1982; pp. 55-59, 64

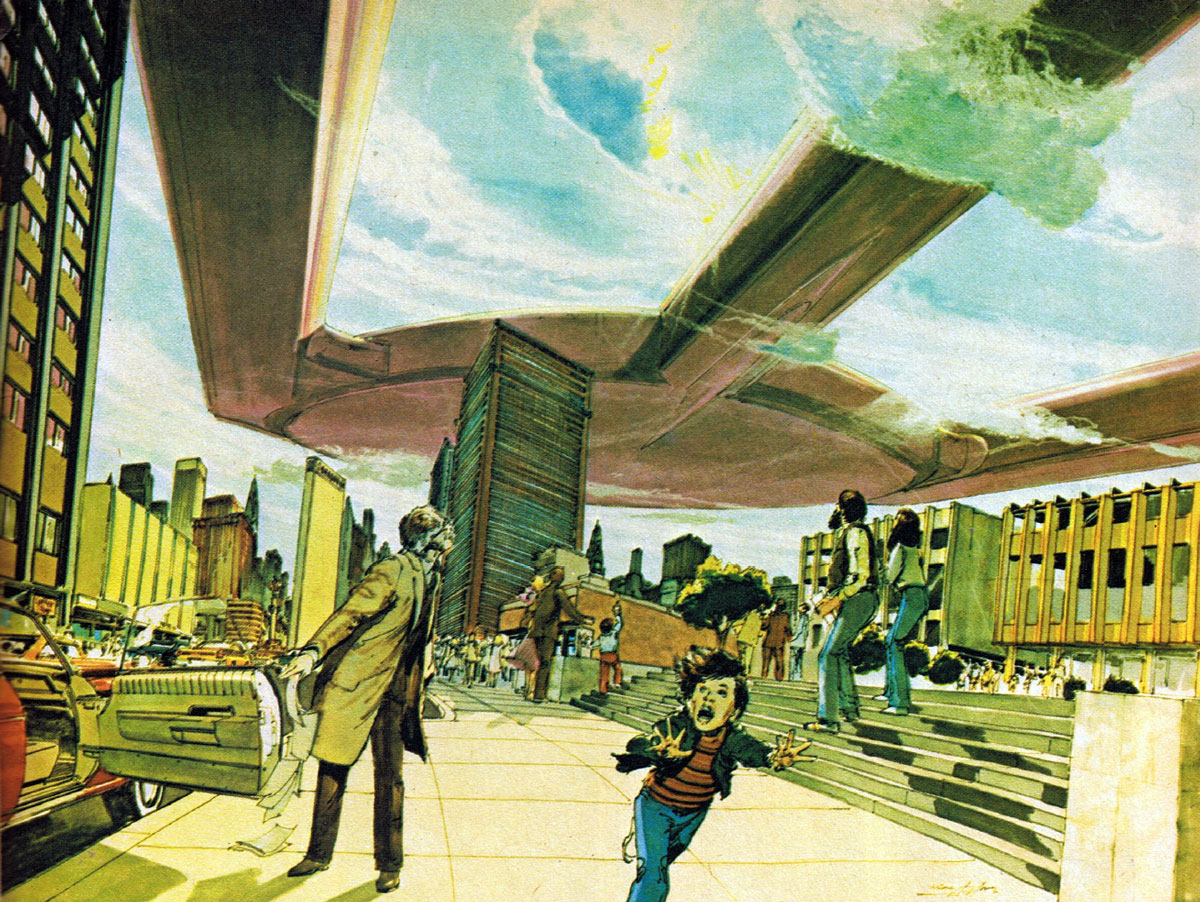

Associate producer and cinematographer of Brainstorm, Richard Yuricich, with Trumbull on one of EEG’s FX stages. Trumbull stands behind an imposing, futuristic cityscape that was built in the miniature shops at EEG, his effects house

1 thought on “ON THE SET OF ‘BRAINSTORM’ WITH DOUGLAS TRUMBULL- by David Hutchison [Starlog]”

Thank you for the upload. It is one of my favorite movies and was shot 3 years before I was born. Fascinating article.