How did finance become the realm of the masters of the universe? Through the rise of the bond market in Renaissance Italy. With the advent of bonds, war finance was transformed and spread to north-west Europe and across the Atlantic. It was the bond market that made the Rothschilds the richest and most powerful family of the 19th century.

We may think power resides with presidents and prime ministers in palaces and parliaments. Not so. In today’s world, real power lies in the hands of an elite group of unassuming men in anonymous, open-plan offices… the men who control the world’s bond market.

Bill Gross is the boss of PIMCO, the world’s biggest bond-trading operation, which manages a portfolio of bonds worth $700 billion. Gross is widely regarded as the king of the bond market. Just call him Mr Bond.

Bonds are the magical link between the world of high finance and the world of political power. Governments will always spend more than they raise in taxation – sometimes shed-loads more – and they make up the difference by selling bonds that pay interest. But – and here’s the magic – if you want to get rid of a bond, the government doesn’t have to give you the cash back. You just take it to a bond market, like the one here at Tokyo Stock Exchange, and sell it.

After the rise of banks, the birth of the bond market was the next big revolution in the history of finance. It created a whole new way for governments to borrow money. The bond market funded the wars that plagued northern Italy 600 years ago. It dictated the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo and created the world’s greatest financial dynasty. It ensured the defeat of the South in the American Civil War. And in modern times, the bond market has brought once wealthy nations, like Argentina, crashing to their knees. Today, governments and companies use bonds to borrow on an unimaginably vast scale. All told, there are bonds out there worth around $85 trillion.

The fortunes of most of us, whether we like it or not, are directly linked to the bond market. If the bond market tanks, then down goes the value of our pensions – and that’s a huge part of our wealth as individuals. In the financial crisis that has gripped the world since the summer of 2007, US government bonds have been seen as a safe haven for investors seeking shelter from the storm of falling property and share prices. So if Bill Gross were to lose faith in those bonds, it would hit the financial world like… well, a thunderball. That’s why this “Mr Bond” has become so much more powerful than the Mr Bond created by Ian Fleming. And that’s why both kinds of bond have a license to kill.

Human Bondage

“War, ” declared the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, “is the father of all things.” It was certainly the father of the bond market. For much of the 14th and 15th centuries, the medieval city-states of Tuscany – Florence, Pisa and Siena – were at war with each other. This was war waged as much by money as by men.

In Pieter van der Heyden’s Battle Of The Money-Bags And Strong-Boxes, piggy banks, treasure chests and barrels full of coins lay into one another with lances and swords in a chaotic free-for-all. The Dutch verses inscribed at the bottom read, “It’s all for money and goods, this fighting and quarrelling.” But what they might just as easily have said is that war is impossible if you don’t have the money to pay for it.

And the way to do that – the ability to finance war through the bond market – was, like so much else, an invention of the Italian Renaissance. Rather than require their own citizens to do the dirty work of fighting, each city hired military contractors – condottieri – who raised armies to annex land and loot treasure from the others. Among the condottieri of the 1360s and 1370s, one stood head and shoulders above the others.

This is his portrait in Florence’s Duomo – a thank-you from a grateful public. Unlikely though it may seem, this master mercenary was an Essex boy. So skilfully did he wage war that the Italians called Sir John Hawkwood Giovanni Acuto – John the Acute. This castle was one of many pieces of prime real estate the Florentines gave him as a reward for his services. But Hawkwood was a mercenary who was willing to fight for anyone who’d pay him – Milan, Padua, Pisa or the Pope.

These dazzling frescoes in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio show the armies of Pisa and Florence clashing in 1364. At that time, Hawkwood was fighting on the side of Pisa. But 15 years later, he’d switched sides. Why? Because Florence was where the money was.

The cost of these incessant wars plunged Italy’s city-states into crisis. Expenditures, even in years of peace, were running at double or more tax revenues. To pay the likes of Sir John Hawkwood, Florence was drowning in deficits.

This wonderful document in the Florentine State Archive shows how the city’s debt had exploded from around 50,000 florins at the beginning of the 14th century to five million by 1427. It was quite literally a mountain of debt, hence the name – the Monte Commune. But from whom could the Florentines possibly have borrowed such a vast sum? The answer is right here – from themselves.

It was a revolutionary idea that would change the world of money for ever. Rather than paying direct tax, citizens were now effectively obliged to lend money to their own government. In return for these forced loans, they received interest.

These debt instruments – simple lines in a ledger – were the original government bonds. And the wonderful thing about them was that if you needed your money in a hurry, you could sell your bonds to other citizens. They were liquid assets. What this record tells us is how Florence turned its citizens into its biggest investors.

This wartime expedient marked the birth of the modern bond market. Everyone was a winner. Bonds had saved the city-state from bankruptcy. The citizens were happy earning their interest. And the bond market let them buy or sell as they saw fit. It seemed as if the problem of public debt had been solved, allowing the citizens of Florence to turn their minds to higher things. But there was just one problem with this brilliant idea.

There was a limit to how many more or less unproductive wars could be waged. The larger the debts of the Italian cities became, the more bonds they had to issue, and the more bonds were issued, the less valuable they looked to investors. And that was exactly the sequence of events in Venice. By the early 16th century, the city had suffered a series of military reverses, and the value of Venetian bonds had taken a hammering.

At their nadir between 1509 and 1529, Venetian Monte Nuovo bonds were trading at just 10% of their face value. Now, if you buy a bond when war is raging, you’re taking a risk – the risk that the city won’t pay you back or pay your interest. On the other hand, remember that the interest is paid on the face value of the bond, so if you can buy it at just 10% of its face value, you’re earning a handsome return of maybe 50%. And that is how the bond market works. In a sense, you get return for the risk you’re prepared to take. At the same time, it’s the bond market that sets interest rates for the economy as a whole. If the state has in effect to pay 50%, then so do all the other borrowers.

The bond market had been invented to help pay for Italy’s wars. But now it was setting interest rates for everyone. Its rise to power had begun. Over the next two centuries, bonds would come to rule the world.

This house was built by the financial dynasty that helped decide the Battle of Waterloo – the dynasty that produced the man they called the Bonaparte of finance, the emperor of the 19th-century bond market. “He is master of unbounded wealth, he boasts that he is the arbiter of peace and war, and that the credit of nations depends upon his nod. Ministers of state are in his pay.” Those words, spoken in 1828 by the Radical Member of Parliament Thomas Duncombe, were describing Nathan Rothschild, bond trader extraordinaire and founder of the London branch of what became the biggest bank in the world. The bond market made the Rothschilds stupendously rich – so rich that they could afford to build 41 stately homes all over Europe. This is number 29 – Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, which has been restored in all its gilded glory by Jacob Rothschild, Nathan’s great-great-great-grandson.

[4th Baron Jacob Rothschild] Well, he was short, fat, obsessive, extremely clever, wholly focused. I can’t imagine he would have been a very pleasant person to have had dealings with.

Between around 1810 and 1836, the five sons of Mayer Amschel Rothschild rose from the obscurity of the Frankfurt ghetto to attain a position of unequalled power in international finance. It was the third son, Nathan, who orchestrated this family triumph from London. Evelyn de Rothschild is Nathan’s great-great-grandson. He recently retired as chairman of Rothschild’s – the bank that Nathan built.

He was very ambitious and he moved to London. I think he was determined. I don’t think he suffered fools lightly. Maybe that’s a family trait.

This is one of the few surviving letters from Nathan Rothschild to his brothers written, as always, in Judendeutsch – that was German transliterated into Hebrew characters – and it gives you an idea of what an extraordinary work ethic the man had and how he tried to impose it on his poor, long-suffering brothers. Just listen to this. “Dear Amschel, I am writing you my opinion because it’s my damned duty to do so. I read your letters, not once, but often 100 times, because you can well imagine that after dinner I don’t read books, I don’t play cards, I don’t go to the theatre. My only pleasure is my business.”

It was this phenomenal drive, allied with innate financial genius, that propelled Nathan from obscurity to mastery of the London bond market. Once again, however, the opportunity for a financial breakthrough came from war.

On the morning of June 18th, 1815, 67,000 British, Dutch and German troops under the Duke of Wellington’s command looked out across the fields of Waterloo, not far from Brussels, towards an almost equal number of French troops commanded by the French Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Battle of Waterloo was the culmination of more than two decades of intermittent conflict between Britain and France. But it was more than just a battle between two armies. It was also a contest between rival financial systems. One, the French, based on plunder. The other, the British, based on debt.

To pay for the war, the British government had sold an unprecedented amount of bonds. According to a long-standing legend, the Rothschild family made their first millions by speculating on how the outcome of the Battle of Waterloo would affect the price of these bonds.

It was this legend of Jewish profiteering that, a century later, the Nazis did their best to embroider. In 1940 Josef Goebbels approved the release of this film, Die Rothschilds. Nathan is seen bribing a French general to ensure the Duke of Wellington’s victory, and then deliberately misreporting the outcome of the battle in London. This triggers panic selling of British bonds, which Nathan then snaps up at bargain-basement prices.

What happened here in 1815 was altogether different. Far from making money from Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon, the Rothschilds were very nearly ruined by it. Their fortune was made not by Waterloo, but despite it.

This is how it really happened. Selling bonds to the public had raised plenty of cash for the British government. But neither bonds nor bank notes were any use to Wellington. To provision his troops and pay Britain’s allies against France he needed a currency that was universally acceptable. Nathan Rothschild was given the job of taking the money raised on the bond market and delivering it to Wellington – as gold. The success of this operation would determine the fate of the warring empires and of all Europe.

This letter marks a turning point in the history of both the Rothschild family, and the British government. It’s dated the 11th of January 1814, and it’s an order from the Chancellor of the Exchequer to the Commissary-in-Chief telling him to appoint Nathan Rothschild – Mr Rothschild – as a British government agent. Nathan’s job was to gather together as much gold and silver as he could find on the European continent and make sure it got to the Duke of Wellington and his army who had just fought their way out of Spain into the South of France. It was an operation that relied heavily on the Rothschilds’ unique pan-European credit network and on Nathan’s ability to mobilise gold the way Wellington could mobilise troops.

Shifting such vast amounts of gold in the middle of a war was hugely risky. Yet, from the Rothschilds’point of view, the hefty commissions they were able to charge more than justified the risks. The Rothschilds soon became indispensable to the British war effort. In the words of the British Commissary-in-Chief… “Rothschild of this place has executed the various services entrusted to him in this line admirably well, and though a Jew, we place a good deal of confidence in him.” The Rothschilds were so effective as war financiers because they had a ready-made banking network within the family – Nathan in London, Amschel in Frankfurt, James in Paris, Carl in Amsterdam and Salomon roving wherever Nathan saw fit. If the price of gold was higher in, say, Paris than in London, James in Paris would sell – and Nathan in London would buy.

[4th Baron Jacob Rothschild] I think their edge over families like the Barings, with whom they were competing, was that they had their brothers in very important financial centres in countries. Now whether that was pre-meditated, whether they thought that through as they got out of the ghetto, it’s hard to believe that they went as far as that. But that’s what happened and once they saw that it was an advantage, they worked on that advantage.

In March 1815, Napoleon returned to Paris from exile in Elba determined to revive his imperial ambitions. The Rothschilds immediately ramped up their gold operation, buying up all the bullion and coins they could lay their hands on. Nathan’s reason for buying this huge stock of gold was simple. He assumed that, as with all Napoleon’s wars, this would be a long one. His gold would be more and more sought after and it would rise in value. It proved to be a near-fatal miscalculation.

Wellington famously called the Battle of Waterloo, “The nearest-run thing you ever saw in your life.” After a day of brutal charges, counter charges and heroic defence, the late arrival of the Prussian Army finally proved decisive. For Wellington, it was a glorious victory. But not for the Rothschilds.

No doubt it was gratifying to Nathan Rothschild to be the first to hear the news of Napoleon’s defeat. Thanks to the swiftness of the Rothschild couriers, he heard it fully 48 hours before Major Henry Percy delivered Wellington’s official despatch to the British Cabinet. But, no matter how early he heard it, the news of Waterloo was anything but good from Nathan’s point of view. He had bargained for something much more protracted. Now he and his brothers were sitting on top of a pile of cash that nobody wanted, to pay for a war that was over.

With the coming of peace, the great armies that had fought Napoleon could be disbanded. That meant no more gold for soldiers’ wages and it meant the price of gold, which had soared during the war, would fall.

Nathan was faced with heavy and growing losses. There was only one possible way out. Nathan could use the Rothschild gold to make a massive and hugely risky bet… on the bond market.

On July 20, 1815, the evening edition of the London Courier reported that Nathan had made “great purchases of stock”, meaning British government bonds. Nathan’s gamble was that the British victory at Waterloo would send the price of British bonds soaring upwards. Nathan bought, and as the price of bonds began to rise, he kept on buying. Despite his brothers’ desperate entreaties to sell, Nathan held his nerve for another year. Eventually, in July 1817, with bond prices up by 40%, he sold his holding. His profits were worth approximately £600 million today. The Rothschilds had shown that bonds were more than just a way for governments to fund their wars. They could be bought and sold in a way that generated serious money. And with money, came power.

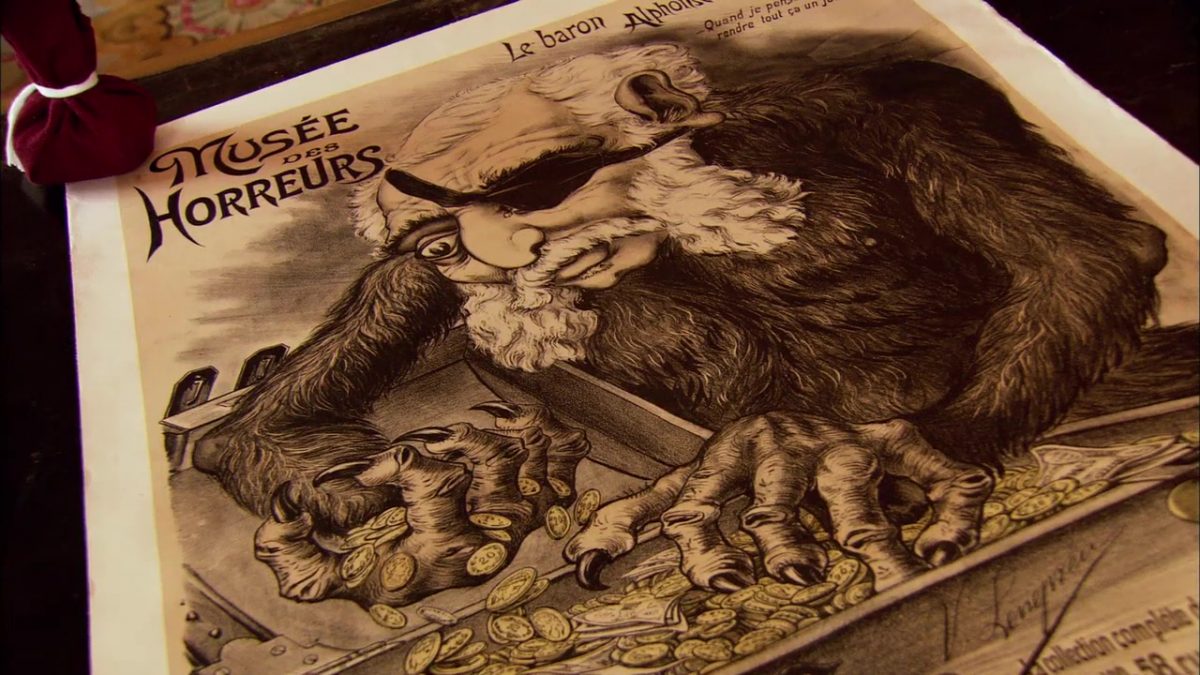

Mayer Amschel Rothschild had repeatedly admonished his five sons, “if you can’t make yourself loved, make yourself feared.” As they bestrode the mid-19th century financial world as masters of the bond market, the Rothschilds were already more feared than loved. But now, they had become hated too. The fact that the Rothschilds were Jewish gave a new impetus to deep-rooted anti-Semitic prejudice.

[4th Baron Jacob Rothschild] Just a few months ago a colleague of mine in my office, who collects posters, found these… Well, this particular, rather extraordinary example of anti-Semitism in a stark form, about the Rothschilds, who were as it were epitomised, to them and others at times, the most extreme forms of undesirable capitalism as practised by Jews.

It was, above all, the Rothschilds’ seeming ability to permit or prohibit wars that aroused the most indignation.

You might have thought that the Rothschilds actually needed war. After all, some of Nathan’s biggest deals had been produced by war. If it hadn’t been for war, 19th-century states wouldn’t have needed to issue bonds for the Rothschilds to buy and sell. But the trouble with war, and even more so with revolution, was that increased the risk that a debtor state might fail to meet its commitments. And that hit the price of existing bonds. By the mid-19th century, the Rothschilds were no longer mere traders, they were fund managers, carefully tending to a vast portfolio of their own government bonds. Now, they stood to lose much more than to gain from conflict.

The Rothschilds had helped decide the outcome of the Napoleonic Wars by putting their financial weight behind Britain. Now they would help decide the outcome of the American Civil War – by choosing to sit on the sidelines. Once again, it was the masters of the bond market who would be the arbiters of war.

50 years after the Battle of Waterloo, and on the other side of the world, another great war would be decided by the power of the bond market. But this time, it would be the vanquished who made the big bet and lost.

The traditional view is that the key turning point in the American Civil War came in June 1863, two years into the conflict. That was the month when Union forces captured Jackson, the Mississippi state capital, and forced a Confederate army to retreat westward to Vicksburg, their backs to the Mississippi River. Surrounded, with Union gunboats bombarding their positions from behind, the Southerners held out for a month before finally laying down their arms. After Vicksburg, the Mississippi was firmly in the hands of the North. The South was literally split in two. Yet this military setback wasn’t the decisive factor in the South’s ultimate defeat. The real turning point came earlier. And it was financial.

200 miles downstream from Vicksburg, where the Mississippi joins the Gulf of Mexico, lies the port of New Orleans. This is Fort Pike, built after 1812 to protect New Orleans from a future British attack. But 50 years later, it wasn’t able to protect the South from a Northern attack when Captain David Farragut seized New Orleans on April 28th, 1862. It was a crucial moment in the Civil War as New Orleans was the principal outlet for the South’s most important export… cotton. Without control over the cotton trade the South’s cause was doomed – because cotton had become the essential ingredient in an ambitious scheme to bring the bond market into the war. Like the Italian city states 500 years before, the Confederate Treasury had initially raised money for the war by selling bonds to its own citizens. But there was a finite amount of capital available in the South. To survive, the Confederacy looked to Europe in the hope that the world’s greatest financial dynasty might help them beat the North as they had helped Wellington beat Napoleon.

Initially, the Confederacy had grounds for optimism. In New York, the Rothschilds’ agent was sympathetic, having opposed the North’s leader, Abraham Lincoln in the presidential election of 1860. But still the Rothschilds hesitated. Lending to the British government to help defeat Napoleon had been one thing. But buying bonds from a bunch of breakaway Southern slave states seemed a risk too far. The Rothschilds decided to stay out.

Yet despite this setback, the Confederate government had an ingenious trick up their sleeves. The trick, like the sleeves themselves, was made of cotton. The South’s idea was to use cotton as collateral to back its bonds. Investors would be comforted to know that if the interest payments dried up they could still demand their cotton instead. The South’s agents went to work selling the bonds in the financial centres of Europe.

When the Confederacy tried to market conventional bonds in European financial centres like Amsterdam’s, investors wouldn’t touch them with a bargepole. But when an obscure French firm named Emile Erlanger and Company offered cotton-backed bonds, it was a completely different story. The key to the success of the Erlanger bonds was that they could be converted into cotton at the pre-war price of six pence a pound. These cotton bonds formed the basis of the South’s new financial strategy. If they could restrict the supply of cotton, its value, and the value of the bonds, would increase. At the same time, the Confederates set out to use cotton to blackmail the most powerful country in the world – Britain.

The routes to the United States of America provided Liverpool with growing volumes of trade and new docks opened on the Mersey in quick succession during the 1800s.

In 1860, the Port of Liverpool was the principal gateway for imports of cotton to the British textile industry, then the mainstay of the Victorian industrial economy. More than 80% of the cotton came from the Southern United States. Now that gave the Confederate leadership hope that they had the leverage to bring in Britain on their side in the Civil War. To ratchet up the pressure, they decided to impose an embargo on all shipments of cotton to Liverpool.

For a while, the South’s strategy worked brilliantly. Cotton prices soared. So did the value of the Confederates’ cotton-backed bonds. And the cotton embargo devastated the British economy. Mills were forced to lay off workers. Eventually, in late 1862, production all but ceased.

This cotton mill in Styal, south of Manchester, employed around 400 workers, but that was just a fraction of the 500,000 people employed by King Cotton across Lancashire. Obviously, with no cotton there was nothing for people to do. By the end of 1862, half the entire workforce of Lancashire had been laid off. A quarter of the population was on poor relief. They called it the “Cotton Famine”, but this really was a man-made famine. Britain was in the doldrums. And the South’s cotton bonds were riding high. Yet the South’s ability to manipulate the bond market depended on one over-riding condition – that investors could be sure of taking physical possession of the cotton which underpinned the bonds if the South failed to make its interest payments. And that’s why the fall of New Orleans on April 28, 1862, was the real turning point in the American Civil War. Now that the South’s main port was in Union hands, any investor who wanted to lay his hands on Southern cotton had to run the Union’s formidable naval blockade.

The Confederates had overplayed their hand. They had turned off the cotton tap, but then lost the ability to turn it back on. By 1863, the mills of Lancashire had found new sources of cotton in China, Egypt, and India and investors were rapidly losing faith in the South’s cotton-backed bonds. The consequences for the Confederate economy were disastrous.

With its domestic bond market exhausted and only two paltry foreign loans, the Confederacy really had no alternative but to print paper dollars, like these ones here in the Louisiana State Museum, to pay for the war. In all, 1. 7 billion dollars’ worth. Now, it’s true that the North also printed paper money, but by the end of the war its “greenbacks” were still worth around 50 pre-war cents, whereas a Southern “greyback” was down to just one cent. What’s more, with more and more of this cash chasing fewer and fewer goods, inflation in the South simply exploded. By January 1865, the price of some goods was up by a factor of 90.

The South had bet everything on manipulating the bond market and had lost. It would not be the last time in history that an attempt to do so would end in ruinous inflation.

Today the global market for bonds is still bigger than the all the world’s stock markets put together. It’s still a market that can make or break governments. Does it surprise you that its key player began his money-making career in the casinos of Las Vegas?

[Bill Gross, CEO Pimco] I was a blackjack player. One of the first professional blackjack players, not to brag, but in the late ’60s, I went to Vegas and applied a card-counting system to try and beat Vegas.

Now this master of understatement is the King of the Bond Market, controller of the biggest bond fund in the world. So what has this got to do with you and me? Well, when Gross buys or sells bonds, it doesn’t just affect financial markets and government policy, it affects the value of our pension funds and the interest rates we pay on our mortgages. There’s only one thing that Mr Bond is afraid of and it’s not Goldfinger. Rather, it’s inflation. The lethal danger that inflation poses is that it undermines the value of being paid a fixed rate of interest on a bond.

[Bill Gross] If inflation goes up to 10% and the value of a fixed-rate interest is only five, then that means that the bond holder is falling behind inflation by 5%.

That’s why, at the first whiff of higher inflation, bond prices fall, and in some cases, keep falling.

To see just how bad things can get when the inflationary genie escapes from the bottle you just have to look at the example of Argentina. Many Argentines date the steady decline of their economic fortunes to a day in February, 1946, when the newly elected President, General Juan Domingo Peron came here to the Central Bank in Buenos Aires. He was astonished at what he saw. “There is so much gold, he marvelled, you can hardly walk through the corridors.” The very name Argentina suggests wealth and plenty – it means “The Land Of Silver”. The river flowing past the capital is the Rio de la Plata, “The Silver River”.

Once upon a time, there used to be two Harrods in the world. One in London, in Knightsbridge, and the other here, in the Avenida Florida, in the heart of Buenos Aires. Founded in 1912, this other Harrods is a reminder that Argentina used to be a rich country. At one time, its per capita income was 18% less than that of the United States. Investors who flocked to buy Argentine bonds hoped that Argentina would become the United States of South America. Well, Argentina’s history since then is a classic illustration that all the resources and talent in the world can be set at nought by chronic financial mismanagement.

There have been many financial crises in Argentine history. But the crisis that hit the country in 1989 was unparalleled.

At the beginning of February, the country was suffering one of the hottest summers on record. In Buenos Aires, the electricity system just couldn’t cope. Five-hour power cuts were commonplace. But these, as it turned out, were the least of Argentina’s problems. As is almost always the case, there were several well-trodden steps to monetary hell.

In step one, the government spends more, much more, than it can raise in taxation. Usually, but not always, it’s because of a war. In Argentina’s case, there were two. One, a civil war between Generals and the Left in the 1970s, the other a foreign war against Britain over the Falkland Islands in 1982. By 1989, the financial system was about ready to blow.

By February, inflation had already reached 10% – per month. Banks were ordered to close as the government tried to lower interest rates and prevent the currency’s exchange rate from collapsing. It didn’t work. In just a month, the austral fell 140% against the dollar. At the same time, the World Bank froze lending to Argentina, saying that the government had failed to tackle the root cause of inflation – a bloated public-sector deficit.

With no cheap loans forthcoming from the World Bank, the government tried to finance its deficit by selling bonds to the public. But investors were hardly likely to buy bonds with the prospect that their real value would be wiped out by inflation in just a matter of days. Nobody was buying. The government was running out of options.

In April, furious customers overturned shopping trolleys after one supermarket announced over the loudspeaker that prices were being raised by 30% immediately. Shops emptied of goods as owners weren’t making enough money to buy new stock.

[‘La Negra’] “It was bad. Very very bad. Because in the morning you had one price and in the afternoon another. So you couldn’t sell because people would lose out. The shop owners would lose out. I would sell at one price, and then it would change. And it was continuous, 3 or 4 times a day the prices changed.”

Government bond prices plunged as fears rose that the Central Bank’s reserves were running out.

With no foreign loans and no-one willing to buy bonds, there was only one thing left for an increasingly desperate government to do – get the Central Bank literally to print more money. But they couldn’t even get that right.

On Friday April 28th, Argentina literally ran out of money. “it’s a physical problem,” the Central Bank Vice-President told a news conference. What he meant was that Argentina’s mint had run out of paper to print new notes, and the printers had gone on strike.

“I don’t know how we’ll do it, “but the money has got to be there on Monday, ” he declared. Yet the faster the printing presses rolled, the less the money was worth. The government was forced to print higher and higher denominations of notes. In May, the price of coffee went up by 50% in a week. Farmers stopped bringing cattle to market as the price for one cow was now the same as for three pairs of shoes.

By June 1989, inflation in Argentina had reached a monthly rate of 100%, an annual rate of roughly 12,000%. To put that into concrete terms, if you wanted to go out for dinner in Buenos Aires on a Saturday night, in May you’d pay 10,000 australes. By June, you’d have to pay 20,000 for the same meal. And by the following month, it would take 60,000. You’ve heard of a fistful of dollars. Well, you needed a drawer full of australes just to buy a square meal.

In June, popular frustration erupted in two days of intense rioting and looting by hungry mobs. At least 14 people died. In a country where a steak and a bottle of wine were on practically every table every day, thousands were eating in soup kitchens or going hungry.

It’s obvious enough who loses from hyperinflation. Very rapidly rising prices are bound to wipe out anybody who’s dependent on an income that’s fixed in cash terms. Groups like academics and civil servants on inflexible monthly salaries, old-age pensioners and, particularly, bondholders living off the interest on their investments. Buenos Aires is absolutely full of antique shops like this one, laden down with jewellery and watches and cutlery, all sold off by middle-class families who just ran out of cash.

In the 1920s, the great economist John Maynard Keynes had predicted the euthanasia of the bondholder, anticipating that inflation would eat up the paper wealth of financial families like the Rothschilds. As inflation swept through the world in the 1970s, Keynes seemed to be proved right. In our time, however, we’ve seen a miraculous resurrection of the bondholder – a comeback by Mr Bond… even in Argentina. The bond market is back, terrifying American officials as they try to fund a massive financial bailout by – you guessed it – selling billions of dollars of freshly minted bonds.

The key to Mr Bond’s revival has been a growth in the number of bondholders… which brings us back to Italy, where the bond market was born 600 years ago. Italy is now a country with one of the most rapidly ageing populations in Europe. In such a greying society, there is a growing demand for fixed-income securities like bonds. But there’s also a strong fear of inflation eating up the real value of pensions and savings. Central bankers suspected of being soft on inflation have to answer to the pensioner’s friend – the bond market. And treasuries planning to spend billions to bail out banks that have gone bust in the current credit crunch have to tread warily, too, if they expect to raise the money by selling yet more bonds.

In modern Europe, as in Renaissance Italy, an equilibrium has been struck between political power and financial exposure. Today, as much as ever, it seems it’s the bond market, our old friend Mr Bond, that really rules the world.

But what if, rather than lending to governments, you prefer to use your money to buy a share in a company? Would that be more or less risky? More or less profitable? In the next episode of the Ascent Of Money, we’ll discover why we find it so hard to learn from financial history, despite nearly 300 years of stock market bubbles and busts.