Mistah Kurtz—He Dead

by Veronica Geng

Viewed as a conventional updating of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness—like one of those attempts to make Crime and Punishment meaningful by setting it in the United States in the nineteen-fifties or to make a movie about interracial marriage universal by using the plot of Othello—Apocalypse Now looks like not much more than a cannibalization. For better and for worse, the movie confirms the idea that a work of art consists of local particulars. To use somebody else’s work of art as a skeleton, you first have to turn it into a skeleton. Where Apocalypse Now is least successful (the last half hour), it seems to have been made by people who have read Conrad with their teeth. Where it is amazingly successful (the first two hours), it takes least from Conrad—or, rather, it takes subtly and delicately, for form and inspiration. The journey upriver through a place of evil (in Conrad, a dark continent ravaged by ivory-mad white traders; in the movie, Vietnam) is a beautiful, classical structure. Francis Coppola’s direction breaks it, with long, fluid set pieces of horror, into equivalents of the long, fluid paragraphs of the speech of Conrad’s Marlow telling “one of [his] inconclusive experiences.” The movie is inconclusive not in the sense that it is meaningless but in the sense that it refuses to interpret itself as it goes along. Coppola at his best does not let us remove ourselves one safe step from what is happening on the screen to the meaning of what is happening on the screen. Coppola has the “weakness”—as Heart of Darkness ironically calls it—of Marlow: “the weakness of many tellers of tales who seem so often unaware of what their audience would best like to hear.” Audiences seem uncertain about how to respond to Apocalypse Now. Perhaps they come in with too much awe or cynicism; or perhaps because Coppola has spent thirty million dollars they expect what he spent it on to be doing all the work. Both times I saw the movie, there were nervous titters, more or less respectfully suppressed, every time it moved into a surprising tone. I reacted this way the first time through, and now think I was wrong to mistrust my laughter. I don’t know what Apocalypse Now is in its entirety (and I am not sure Coppola does), but for most of the way it is the blackest comedy I have ever seen on the screen, taking its spirit and tone not from Conrad but from—this is the shortest way to say it—Michael Herr.

Herr’s reporting from Vietnam (collected in his book Dispatches) shows us a war that justifies Baudelaire’s statement “The comic is one of the clearest Satanic signs of man”: people living through Vietnam as pulp adventure fantasy, as movie, as stoned humor, as a collage that Herr once saw in a helicopter gunner’s house, on a wall near a poster of Lenny Bruce—a map of the western United States with Vietnam reversed and fitted over California. Other reporters brought back pieces of the same picture, but Apocalypse Now seems indebted to the special intensity of Herr’s vision of the heart of the Vietnam War’s darkness as “that joke at the deepest part of the blackest kernel of fear.”

Herr also wrote the movie’s narration. It is spoken as a voice-over by Martin Sheen, as Captain Benjamin Willard, and expectations that Willard will be someone like Marlow may account for the first waves of nervous tittering. His first words in the movie are “Saigon. Shit.” Willard talks in the easy ironies, the sin-city similes, the weary, laconic, why-am-I-even-bothering-to-tell-you language of the pulp private eye. “I hardly said a word to my wife until I said yes to a divorce. . . . I’m here a week now, waiting for a mission, getting softer. . . . Everyone gets everything he wants. I wanted a mission. And for my sins they gave me one. Brought it up to me like room service. . . . How many people had I already killed? There were those six I knew about for sure. . . . Charging a man with murder in this place was like handing out speeding tickets at the Indy 500. . . . Cut ’em in half with a machine gun and give ’em a Band-Aid. It was a lie.” (Herr’s style in Dispatches is not innocent of a certain amount of macho attitude-striking, but he clearly knows you don’t write the way Willard talks and mean it. And he shows a flair for parody in a mock dispatch from an old-guy reporter: “. . . like your kid or your brother or your sweetheart maybe never wanted much for himself never asked for anything except for what he knew to be his some men have a name for it and they call it Courage.”) Our first look at Willard is the classic opening of the private-eye movie: his face seen upside down, a cigarette stuck to his lip, under a rotating ceiling fan (all this superimposed on a dreamlike scene of helicopters brushing across the screen, a row of palm trees suddenly bursting into flame), and then the camera moving in tight closeup over his books, snapshots, bottle of brandy, cigarettes, Zippo, and, finally, obligatory revolver on the rumpled bedsheets. This guy is not Marlow. He is a parody—maybe a self-created one—of Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s L.A. private eye.

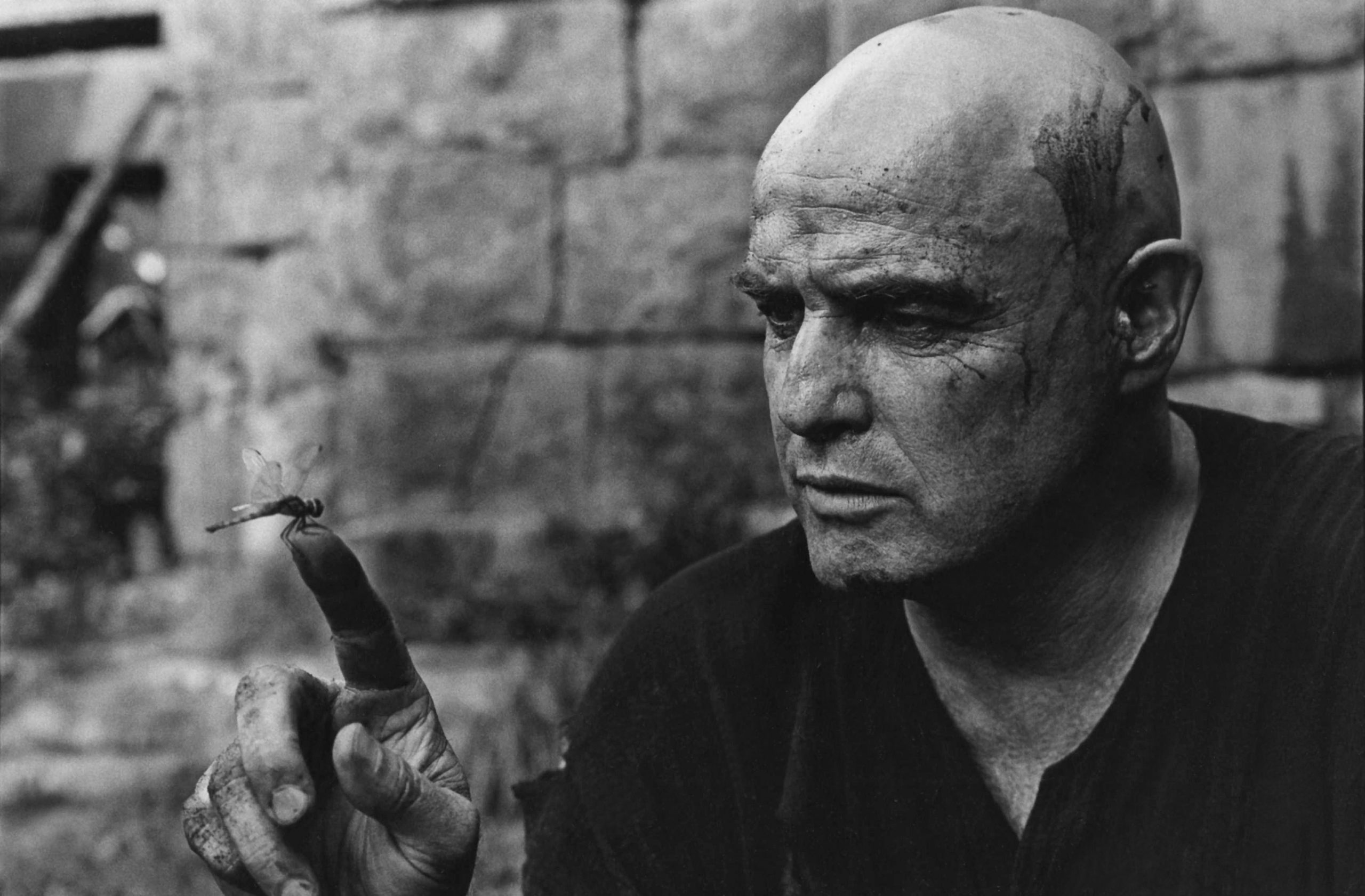

The scene where Willard gets his mission—to travel upriver to Cambodia and kill Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando)—has pulp overtones, too. The studied business with dossiers and tapes; the comic-strip-inset closeup of a photograph being passed from hand to hand; the B-movie readings of lines derived from Conrad (G. D. Spradlin, a fine actor, as the general: “His ideas . . . methods . . . became . . . unsound”) and of lines that could only come from a B-movie (Spradlin again: “Out there with these natives, it must be a temptation to play God”); the sinister, silent, vaguely Oriental-looking civilian (Jerry Ziesmer) who finally delivers the most evasive bit of bureaucratic jargon—it is all so carefully poised between real men and the trash-adventure-fiction sources of their posturing that we don’t know which came first, or in which category to respond. When the young colonel (Harrison Ford), whose nervous throat-clearing shades slightly toward the comic, says that Kurtz’s Montagnard followers worship him to the point where they “follow every order, however ridiculous,” the word “ridiculous” is so off that it starts another wave of tittering. (Listen, you Montagnards, I know this is going to sound really silly . . .) You can almost see the line in a dialogue balloon above Ford’s head. The movie is getting the feel of a “Sgt. Fury” comic book with almost no distortion. When we hear Colonel Kurtz’s voice on tape—“I watched a snail crawling along the edge of a straight razor. That’s my dream”—it sounds like a description of the scene, in more ways than one. The pace of the scene is painfully slow. It is the pace of Willard’s perception of whatever is not war; and how very slow that is we cannot know until we experience the speeding intensity of what follows.

With the first of its war scenes, Apocalypse Now becomes a horror comedy. It is what Dr. Strangelove might have been after the bomb fell, except that the comedy is not exaggerated and detached from suffering in a way that tells us we may safely laugh; it is realistic, and it exists simultaneously with realistic horror rendered with the physical brilliance and amplitude of 2001. The horror is not drained off, as it is by the easy absurdism of The Deer Hunter, into a symbolic game; and the comedy is not drained off, as it is by the wordplay of Catch-22, into a cute craziness. Robert Duvall’s Lieutenant Colonel Kilgore (a Strangelove name if there ever was one; it would not surprise me to learn that it jumped out at the screenwriters from the page in Dispatches that mentions Kilgore, Texas), who leads an Air Cavalry attack on a Vietnamese village, is balanced on a razor edge between Strangelove’s Buck Turgidson and a real man emulating Patton. Kilgore is not, like Turgidson, a caricature; he is someone who has internalized a caricature. His surrealistic excesses are generated not by the demands of comedy but by demands from inside a realistic character. Kilgore is a mutant. These war scenes, in their horror and comedy, and their relentless beauty, get at something Michael Herr described: “Maybe you couldn’t love the war and hate it inside the same instant, but sometimes those feelings alternated so rapidly that they spun together in a strobic wheel rolling all the way up until you were literally High On War, like it said on all the helmet covers.”

There are three such extraordinary sequences in the movie, progressing from deadly efficiency controlled by Kilgore’s authority to chaos controlled by no one. They are not parallels to passages in Conrad but reimaginings of what he described as “imbecile rapacity,” as “an inextricable mess of things decent in themselves but that human folly made look like the spoils of thieving,” and as “black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confusedly in the greenish gloom . . . in all the attitudes of pain, abandonment, and despair.” In the third of these sequences, in an incident almost identical to one reported by Herr, a black Marine (Herb Rice) with a ghostly unchanging stare and a kind of psychic aim uses a hand-decorated grenade launcher to kill a Vietnamese who is some distance from the bunker. In Herr’s account, the Vietnamese is screaming with pain, trapped and wounded on the wire surrounding the outpost; in the movie, he is taunting the Marines with obscenities. In this transformation of mutual suffering into revenge—and in a fourth scene, the so-called puppy-sampan scene, in which Willard takes the view that when you start something, you have to finish it, however brutally—I thought I detected the tooth and claw of John Milius (who wrote the screenplay with Coppola, and who was responsible for the screenplays of Jeremiah Johnson, The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, and, with Michael Cimino—director of The Deer Hunter—Magnum Force). But Milius’s adulation of violence and will seems to have mostly been held to its proper place by Coppola. Willard is not Marlow: his narration does not have a deep historical perspective, and it is spoken in a psychological state as numbed as the one he is in on the screen. He is not even Marlowe: he is not above the garish evil that surrounds him. Where Willard is pitiless, Apocalypse Now is not. The men on the boat, whom we get to know (Frederic Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, and Larry Fishburne), keep the movie from spiralling off into the impersonal, and we suffer for everyone in it. Though this is a matter of instinct, it seems to me that Apocalypse Now earns every second of its display of evil, because it has coherence, truthfulness, and conviction—up to a point.

The point is Kurtz. By the time Willard reaches Kurtz, Coppola has not made a movie version of Heart of Darkness; he has made his own movie—one in a class with Lina Wertmüller’s Seven Beauties, not just in its somewhat different use of comedy and horror but in its refusal to go for generalizations instead of particulars. Kurtz, the biggest, fattest temptation to generalization in English literature, has no more place in Coppola’s movie than Raskolnikov or Othello. Yet he is the only character Coppola takes literally—right down to his name—from Conrad. Maybe Coppola thought he could show us not just evil but Evil. Maybe he could not think of any other reason to send Willard upriver. Most likely, he just fell in love with the romantic idea of Kurtz, Kurtz, Kurtz of the voice, the “bewildering,” “illuminating,” “exalted,” “contemptible” voice, and with the idea of Brando as Kurtz. The movie begins to parade big ideas, to partake of Kurtz’s grandiosity. Coppola is not content with having shown us Herr’s “joke at the deepest part of the blackest kernel of fear;” he wants to show us Conrad’s “meaning,” which is not inside Marlow’s tale “like a kernel but outside, enveloping the tale which brought it out only as a glow brings out a haze.” Marlow calls Kurtz “that pitiful Jupiter.” Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s camera reveres Brando’s shaved skull, defined by a crescent of light, the way 2001 reveres the solar system. And the movie collapses, as 2001 does, in a final attempt to show the unshowable. 2001 at least acknowledges the impossibility of showing it in a normal way. Apocalypse Now falters in conviction, making me feel the way I would have if 2001 had ended with some stock green men and Brando, in his Jor-El makeup, as the king of Jupiter.

Reviewing a movie version of The Picture of Dorian Gray, James Agee wrote that he could not understand why Gray’s depravity should “culminate in a couple of visits to a dive where an old man plays Chopin.” It is no easier to understand why Kurtz’s career should culminate in a poetry reading. In Conrad, Kurtz’s reading poetry is an ironic detail, mentioned in an aside by one of his admirers (whom the movie turns into a stoned photojournalist, rather hammed by Dennis Hopper); the movie coarsens the reference by staging it as a big cultural number. Perhaps Milius and Coppola could not write dialogue that would show off the famous Kurtz-Brando voice half so well as T. S. Eliot, but this should have told them something about the pretentiousness of their approach to Kurtz. Coppola might at least have instructed Brando to read from Eliot as ineptly as he elsewhere pronounces “primordial” (it comes out “primord’l”), to suggest the maudlin falsity you hear when criminals quote poetry. If the movie has an anti-Marlow, why not an anti-Kurtz? When Willard, having slain the monster, sits down, covered with blood, at Kurtz’s typewriter, I almost wanted him to start typing and the camera to close in on the page: “Kurtz was sleeping the big sleep now.”

The New Yorker, September 3, 1979