by Mark Crispin Miller

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY A SYNOPSIS

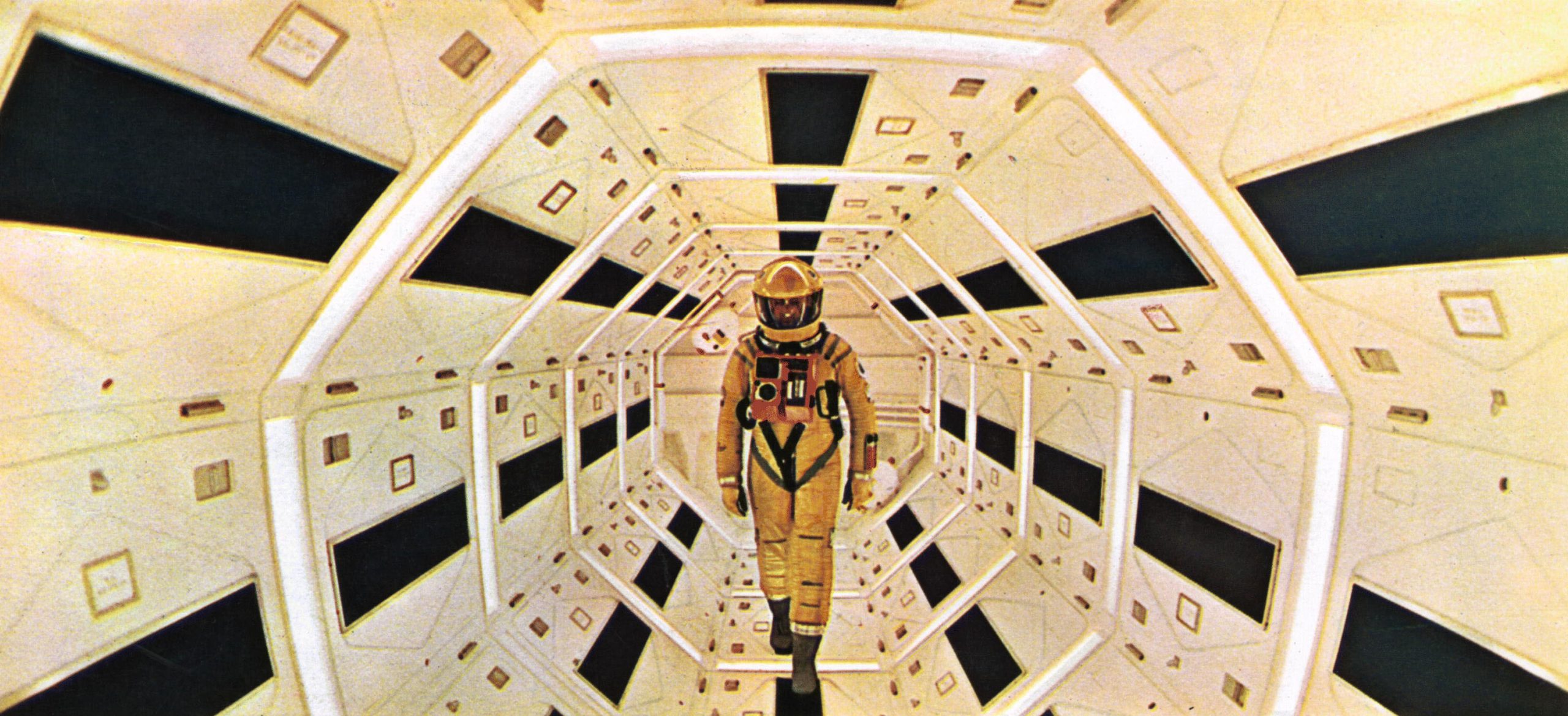

The prehistoric past. A small tribe of apemen lives on a rocky hillside, in constant terror of neighbouring carnivores and quarrelling with a rival tribe for the possession of a water hole. One morning they wake to find before them a mysterious black monolith. When their initial terror has subsided, one of them, inspired by the slab, learns how to use bone clubs to hunt for food. Four million years later, space scientist Doctor Heywood R. Floyd arrives on the moon to investigate a similar black slab which has been found buried deep below the surface and is now emitting powerful signals in the direction of Jupiter. The giant spaceship ‘Discovery’ sets out on a nine-month voyage to Jupiter, manned by astronauts Bowman and Poole, with three colleagues kept in a state of hibernation and a new and infallible computer, HAL 9000, in overall control. In deep space HAL deliberately causes a minor failure, and when Poole ventures outside the ship in his space pod to repair the fault, HAL terminates the life functions of the hibernating crewmen and maroons him in space. Bowman reduces a contrite and fear-stricken HAL to impotence by disconnecting his memory banks, and continues his journey alone. Approaching Jupiter, he sees a strange black slab in orbit among the planet’s moons; suddenly he is sucked into a new dimension, where man’s laws of time and space no longer apply, an infinity of whirling landscapes, worlds in creation and exploding galaxies. Finally he finds himself in an elegant apartment, and his aged and dying self is confronted by one of the mysterious monoliths.

He reaches out towards it, to be born again, the foetus of a new, transcended Man.

* * *

Dear Mr Kubrick: My pupils are still dilated, and my breathing sounds like your soundtrack. I don’t know if this poor brain will survive another work of the magnitude of 2001, but it will die (perhaps more accurately “go nova”) happily if given the opportunity. Whenever anybody asks me for a description of the movie, I tell them that it is, in sequential order: Anthropological, camp, McLuhan, cybernetic, psychedelic, religious. That shakes them up a lot. Jesus, man, where did you get that incredibly good technical advice? Whenever I see the sun behind a round sign, I start whistling Thus Spake Zarathustra. My kettledrum impression draws the strangest looks.

Dear Mr Kubrick: Although I have my doubts that your eyes will ever see this writing, I still have hopes that some secretary will neglect to dispose of my letter. I have just seen your motion picture and I believe – please, words, don’t fail me now – that I have never been so moved by a film – so impressed – awed – etc. The music was absolutely on a zenith. The Blue Danube’ really belonged in some strange way, and the main theme with its building crescendos was more beautiful than John Lennon’s ‘I Am the Walrus’, and from me that’s a compliment. The story in Life magazine, of course, showed the most routine scenes, as Life has a tendency to eliminate any overwhelming virtue in a motion picture, and the three best scenes were lumped together and were almost unrecognizable. But lest I run off at the mouth, let me conclude by saying that if the Academy of ill-voted Oscars doesn’t give you a multitude of awards in 1969,1 will resign from humanity and become a soldier.

Twenty-five years later, Kubrick’s fan mail has an unintended poignancy – in part (but only in part) because the letters are so obviously dated. Those fierce accolades are pure 60s. To re-read such letters now – and Jerome Agel’s 1970 The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, the ecstatic, crazed hommage that includes them – is to look back on a cultural moment that now seems as remote from our own as, say, those hairy screamers of pre-history, erect with murderous purpose at the water hole, might seem from the low-key Doctor Heywood R. Floyd, unconscious on his umpteenth voyage to the moon.

Privilege and power

The film’s first devotees were knocked out, understandably, by its “incredible and irrevocable splendor” (as another letter-writer phrased it). Others were troubled – also understandably – by the film’s disturbing intimation that, since “the dawn of man” so many, many centuries ago, the human race has got nowhere fast. That subversive notion is legible not only in the famous match cut from the sunlit bone to the nocturnal spacecraft (two tools, same deadly white, both descending) but throughout the first two sections of the narrative: indeed, the negation of the myth of progress may be the film’s basic structural principle. Between the starved and bickering apes and their smooth, affable descendants there are all sorts of broad distinctions, but there is finally not much difference – an oblique, uncanny similarity that recurs in every human action represented.

In 2001, for example, the men feed unenthusiastically on ersatz sandwiches and steaming pads of brightly coloured mush – food completely cooked (to say the least) and slowly masticated, as opposed to the raw flesh furtively bolted by the now carnivorous apes; and yet both flesh and mush appear unappetising, and both are eaten purely out of need. Similarly, in 2001 the men are just as wary and belligerent, and just as quick to square off against tribal enemies, as their tense, shrieking forebears – although, as well-trained professionals and efficient servants of the state, they confront the other not with piercing screams and menacing gestures but by suddenly sitting very still and speaking very quietly and slowly: “… I’m… sorry, Doctor Smyslov, but, uh… I’m really not at liberty to discuss this…” Thus Doctor Floyd, although seated in an attitude of friendly languor (legs limply crossed, hands hidden in his lap), fights off his too inquisitive Soviet counterpart just as unrelentingly as, tens of thousands of years earlier, the armed apes had crushed their rivals at the water hole (which recurs here as a small round plastic table, bearing drinks, and again the locus of contention). Now, as then, the victor obviously wields a handy instrument of his authority (although this time it’s a briefcase, not a femur); and now, as then, the females merely look on as the males fight it out. (There is no matriarchal element in Kubrick’s myth.)

More generally, the scientists and bureaucrats, and the comely corporate personnel who serve them (polite young ladies dressed in pink or white), are all sealed off – necessarily – from the surrounding vastness: and here too the cool world of 2001 seems wholly unlike, yet is profoundly reminiscent of, the arid world where all began. Back then, the earthlings would seek refuge from the predatory dangers of the night by wedging themselves, terrified, into certain natural hiding places and even in daylight would never wander far from that found ‘home’ or from one another, even though the world – such as it was – lay all around them. Likewise, their remote descendants are all holed up against the infinite and its dangers – not in terror any more (they seem to have forgotten terror), and surely not in rocky niches (their habitats are state creations, quietly co-run by Hilton, Bell and Howard Johnson), but in a like state of isolation in the very midst of seeming endlessness.

Herein the world of 2001 recalls the pre-historic world before the monolith gives ‘man’ his first idea; once that happens, the species is no longer stuck in place. Made strong by their new carnivorous diet, and with their hands now mainly used to smash and grab, the ape-men have already visibly outgrown their former quadrupedal posture (they are standing – for the first time – when they come back to the water hole), and so are ready to move on. “A new animal was abroad on the planet, spreading slowly out from the African heartland,” writes Arthur C. Clarke in his novelisation of the film – which, of course, elides that historic episode, along with all the rest of human history, thereby taking us from one great dusk to another. When ‘Moon-Watcher’ (as Clarke calls him) exultantly flings his natural cudgel high into the air, that reckless gesture is the film’s only image of abandon and its last ‘human’ moment of potentiality – for, as the match cut tells us, it’s all downhill from there.

However, although the film takes us straight from one twilight moment to another, the first is very different from the next – indeed, the two are almost perfect opposites. At first, humankind nearly dies out because there is no science: no one knows how to make anything, and so those feeble simians cannot fight off the big cats, bring down the nutritious pigs, take over fertile territory, set up proper shelters and otherwise proceed to clear away the obstacles, and wipe out the extremes, of mere nature – through that gradual subjection turning into men. And yet that long, enlightened course of ours (the film suggests) has only brought us back to something too much like the terminus we once escaped – only this time it is not the forces of mere nature (instincts and elements) that threaten to unmake us, but the very instrumentality that originally saved us. In 2001, in other words, there is too much science, too much made, the all-pervasive product now degrading us almost as nature used to do. The match cut tells us not just that we’re on the downswing once again, but that, this time, what has reduced us is our absolute containment by, and for the sake of, our own efficient apparatus. Hence Doctor Floyd is strapped inside one such sinking ship, and quite unconscious of it, whereas Moon-Watcher simply used his weapon, and did so with his eyes wide open. That first image of the dozing scientist is a transcendent bit of satire, brilliantly implying just how thoroughly man has been unmade – stupefied, deprived, bereft – by the smart things of his own making: a falling-off, and/or quasi-reversion, that is perceptible only through critical contrast with what precedes it.

Emboldened by hard protein, the apes at once start making war: mankind’s first form of organised amusement, Kubrick suggests, and (as all his films suggest) one whose attraction can never be overcome by the grandiose advance of ‘civilisation’ – on the contrary. In Kubrick’s universe, the modern state is itself a vast war machine, an enormous engine of displaced (male) aggression whose purpose is to keep itself erect by absorbing the instinctual energies of all and diverting them into some gross spectacular assault against the other. These lethal – and usually suicidal – strikes are carried out by the lowliest members of the state’s forces (the infantry, the droogs, the grunts; ‘King’ Kong, Jack Torrance) against an unseen enemy, and/or – ultimately – some isolated woman, while those at the rear, and at the top, sit back and enjoy the rout vicariously. There is, in short, a stark division of labour in that cold, brilliant, repetitious world of jails and palaces, hospitals and battlefields. It is the function of the lowly to express – within strict limits, and only at appointed times and places – the bestial animus that has long since been repressed and stigmatised, and that (therefore) so preoccupies the rest of us. Thus Alex’s droogs, the grunts under Cowboy’s brief command, and the doomed Jack Torrance all revert, as they move in on their respective prey, to the hunched and crouching gait of their first ancestors sneaking towards the water hole.

Meanwhile, it is the privilege of those at the top – “the best people”, as certain characters in Barry Lyndon and The Shining term them – to sit and (sometimes literally) look down on all that gruesome monkey business, sometimes pretending loudly to deplore it, yet always quietly enjoying it (whether or not they have themselves arranged it in the first place). Such animal exertion is, for them, a crucial spectatorial delight, as long as it happens well outside their own splendid confines – at the front, or in the ring, or in some remote suburban house, or in the servants’ quarters at the Overlook, or in the ruins of Vietnam.

When, on the other hand, someone goes completely ape right there among them, that feral show is not at all a pleasure but an indecorum gross and shattering – whether played as farce, like General Turgidson’s clumsy tussle with the Soviet ambassador in Dr Strangelove (“Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!”), or as a grotesque lapse, like Barry Lyndon’s wild and ruinous attack on his contemptuous stepson. Such internal outbursts threaten “the best people” very deeply: not only by intimating a rebellious violence that might one day destroy them, and their creatures, from without (as nearly happens to Marcus Crassus in Spartacus, or as happens to Sergeant Hartman in Full Metal Jacket), but by reminding those pale, cordial masters that, although they like to see themselves as hovering high above the brutal impulse, they themselves still have it in them. That rude reminder the pale masters cannot tolerate, for their very self-conception, and their power, are based directly on the myth of total difference between themselves and those beneath them. It is the various troops and thugs, those down and out there on the ground, who do the lethal simian dance, because they are primitives. We who do our work in chairs, observing those beneath us, setting them up for this or that ordeal and then watching as they agonise, are therefore beings of a higher order, through this sedentary act confirming our ‘humanity’.

Conditioning and castration

Doctor Floyd is just such a ‘human’ being. If he never appears gazing coolly down on others as they suffer, as do the generals in Paths of Glory or the Ludovico experts in A Clockwork Orange, that omission does not connote any relative kindliness, but is merely one reflection of his total separation from reality: Doctor Floyd never callously looks down on suffering because, within his bright, closed universe-within-a-universe, there is no suffering (nor any physical intensity or emotional display of any kind) for him to look down on. For that matter, Doctor Floyd never really looks at anything, or anyone, until the climax of his top-secret visit to the moon, when he looks intently at the monolith, and even touches it (or tries to). Prior to that uncanny action, the scientist’s gaze is, unless belligerently opaque (as it becomes in his brief ‘fight’ with Smyslov), consistently casual, affable and bored, the same pleasant managerial mask whether it confronts some actual stranger’s face, the video image of his daughter’s face, or that synthetic sandwich.

Although he floats, throughout, at an absolute remove from any site of others’ gratifying pain, Doctor Floyd is nonetheless inclined, like all his peers in Kubrick’s films, to see himself as definitively placed above the simian horde – which is, in his case, not just some cowering division or restive troupe of gladiators, but his own planet’s entire population. As he would presume himself in every way superior to the proto-men of aeons back, so does he presume himself – and, of course, the Council, which he represents – far superior to his fellow-beings way back “down” (as he persists in putting it) on earth. Those masses, he argues, need to be protected from the jarring news that there might be another thinking species out there – hence “the need for absolute secrecy in this”. “I’m sure you’re all aware of the extremely grave potential for cultural shock and social disorientation contained in this present situation,” he tells the staff at Clavius, “if the facts were suddenly made public without adequate preparation – and conditioning.” That last proviso makes it clear that Doctor Floyd is, in fact, ideologically a close relation to those other, creepier doctors at the Ludovico Institute; the whole euphemistic warning of “potential cultural shock” betrays his full membership of that cold, invisible elite who run the show in nearly all Kubrick’s films, concerned with nothing but the preservation of their own power. Surely, what Doctor Floyd imagines happening “if the facts were suddenly made public” would be uncannily like what we’ve seen already: everybody terrified at first, and then, perhaps, the smart ones putting two and two together and moving, quickly, to knock off those bullying others who have monopolised what everybody needs – “the facts” having instantly subverted those others’ ancient claims to an absolute supremacy.

The film itself is thus subversive, indirectly questioning Floyd’s representative ‘humanity’ through satiric contrast with his grunting antecedents. At first, the safe and slumbering Doctor Floyd seems merely antithetical to the ready, raging apes. Whereas those primates – once they have tasted meat, then blood – were all potential, standing taut and upright at the water hole, their leader fiercely beckoning them forward, Doctor Floyd is placid, sacked-out, slack: as smooth of face as they were rough and hairy, as still as they were noisy and frenetic, as fully dressed (zipped up and buckled in) as they were bare – and, above or underneath it all, as soft as they were hard. If they were the first exemplars of the new and savage species homo occidens (and only secondarily, if at all, fit to be entitled homo sapiens), the scientist, unconscious in his perfect chair, exemplifies the old and ravaged species homo sedens. As he dozes comfily, his weightless arm bobs slow and flaccid at his side, his hand hangs lax, while his sophisticated pen floats like a minispacecraft in the air beside him. It is a comic image of advanced detumescence – effective castration – as opposed (or so it seems) to the heroic shots of Moon-Watcher triumphing in ‘his’ new knowledge of the deadly and yet death-defying instrument: his sinewy arm raised high, his grip tight, his tool in place, he seems to roar in ecstasy as he pulverises the bones lying all around him (“Death, thou shalt die!”), and the pigs crash lifeless to the ground, as limp as Doctor Floyd looks minutes later.

The seductive waltz

Although seemingly so different from the simians, however, Doctor Floyd is not only their enfeebled scion but also, deep down, their brother in aggressiveness: a relation only gradually perceptible in his various muted repetitions of the apes’ outright behaviours. As his subdued showdown with the Soviets recalls the frenzied action at the water hole, so does his mystified authority recall Moon-Watcher’s balder primacy, the scientist relying not, of course, on screaming violence to best his enemies and rally his subordinates, but on certain quiet managerial techniques (body language, tactical displays of informality, and so on). His inferiors are just as abject towards him as Moon-Watcher’s were towards that head monkey, although the later entities display their deference towards the manager not, of course, by crouching next to him and combing through his hair for nits, but just by sucking up to him, placating him with nervous, eager smiles and stroking him with witless praises: “Y’know, that was an excellent speech you gave us, Heywood!” “It certainly was!” “I’m sure it beefed up morale a helluva lot!” In such dim echoes of the apes’ harsh ur-society we can discern the lingering note of their belligerence – as we can still perceive their war-like attitude throughout the antiseptic world of their descendants, who are still cooped up in virtual fortresses and still locked into an arrangement at once rigidly hierarchical and numbingly conformist, the clean men as difficult to tell apart as were their hunched hairy forebears.

Thus is the primal animus still here; indeed, it is now more dangerous than ever, warfare having evolved from heated manual combat to the cool deployment of orbiting atomic weapons (one of which sails gently by as The Blue Danube’ begins). Yet while the animus has taken on apocalyptic force, its expression among human beings is (paradoxically, perhaps) oblique, suppressed, symbolic, offering none even of that crude delight which the near-anhedonic simians had known: the thrill of victory (as the sportscasters often put it), and, inextricable from that, the base kinetic entertainment of (as Alex often puts it) “the old ultra-violence”. Such overt and bestial pleasures have been eliminated from the computerised supra-world of the Council and its employees (although not from life back “down” on earth, as A Clockwork Orange will, from its very opening shot, remind us). Just as the animal appetite has, in those white spaces, been ruthlessly denied, so have all other pleasures, which in Kubrick’s universe (as in Nietzsche’s and in Freud’s) derive straight from that ferocious source. In the world of Doctor Heywood Floyd, it is only the machines that dance and couple, man having had, it would appear, even his desires absorbed into the apparatus that, we thought, was meant to gratify them.

As ‘The Blue Danube’ starts to play, its old, elegant cadences rising and falling so oddly and charmingly against this sudden massive earthrise, the various spacecraft floating by as if in heavenly tranquillity, there is, of course, no human figure in the frame – nor should there be, for in this “machine ballet” (as Kubrick has called it) live men and women have no place. Out here, and at this terminal moment, all human suppleness, agility and lightness, all our bodily allure, have somehow been transferred to those exquisite gadgets. Thus the hypnotic circularity of Strauss’s waltz applies not to the euphoric roundabout of any dancing couple, but to the even wheeling of that big space station. Thus, while those transcendent items sail through the void with the supernal grace of seraphim, the stewardess attending Doctor Floyd staggers down the aisle as if she’s had a stroke, the zero gravity and her smart “grip shoes” giving her solicitous approach the absurd look of bad ballet.

Her image connotes not only an aesthetic decline (Kubrick had idealised the ballerina-as- artist in his early Killer’s Kiss), but a pervasive sexual repression. With the machines doing all the dancing, bodies are erotically dysfunctional – an incapacity suggested by Kubrick’s travesties of dance. In A Clockwork Orange he would again present a gross parody of ballet: in the scene at the Derelict Casino, where Billyboy’s droogs, getting ready to gang-rape the “weepy young devotchka”, sway and wrestle with her on the stage, their ugly unity and her pale struggle in their midst suggesting a balletic climax turned to nightmare. There, eros is negated crudely by male violence. In 2001, the mock ballet implies no mere assault on the erotic but its virtual extirpation, its near-super-annuation in the world of the machine. Here, every pleasurable impulse must be channelled into the efficient maintenance of that machine, which therefore exerts as inhibitive an influence as any fierce religion. Stumbling down the aisle, the stewardess looks, in her stiff white pants-suit and round white padded hat (designed to cushion blows against the ceiling), like a sort of corporate nun, all female attributes well hidden. And so it is appropriate that, as she descends on the unconscious Doctor Floyd, her slow approach does not recall, say, Venus coming down on her Adonis, but suggests instead a porter checking on a loose piece of cargo, as she grabs his floating pen and re-attaches it to his oblivious trunk.

Hermetic spaces

The stewardess dances not a fantasy of some delightful respite from the waking world, but only further service to, and preparation for, that world. Likewise ‘The Blue Danube’ refers not to the old sexual exhilarations of (to quote Lord Byron) the “seductive waltz”, but only to the smooth congress of immense machines. As Doctor Floyd slumps in his chair, the flight attendant re-attaching his loose implement, the very craft that holds them both (a slender, pointed shuttle named Orion) is itself approaching, then slides with absolute precision into, the great bright slit at the perfect centre of the circular space station, the vehicles commingling as they do throughout the film – and as the living characters do not, as far as we can see. Orion having finally ‘docked’, the waltz comes to its triumphant close – and Kubrick cuts, on that last note, to an off-white plastic grid, an automatic portal sliding open with a long dull whirr. There first appears, seated stiffly in the circular compartment, another stewardess, a shapely and impassive blonde dressed all in pink and manning the controls, and then, two seats away from her, there again is Doctor Floyd, now wide awake and holding his big briefcase up across his lap like a protective shield. He zips it shut. “Here you are, sir,” she says politely (and ambiguously). “Main level, please.” “Alright,” he answers, getting up. “See you on the way back.”

The human characters are thus maintained – through their very posture and deportment, the lay-out of the chill interiors, their meaningless reflexive courtesies – in total separation from each other, within (and for the sake of) their machines, which meanwhile interpenetrate as freely as Miltonic angels. And yet there is a deeply buried hint that even up in these hermetic spaces, people are still sneaking off to do the deed. “A blue, woman’s cashmere sweater has been found in the restroom,” a robotic female voice announces, twice, over the space station’s PA system just after Doctor Floyd’s arrival. That abandoned sweater may well be the evidence of the same sort of furtive quickie that takes place in General Turgidson’s motel room in Dr Strangelove, or that, in A Clockwork Orange, a doctor and nurse enjoy behind the curtains of a hospital bed while Alex lies half-dead nearby. Given Kubrick’s penchant for self-reference, it maybe that, in conceiving that aside about the cashmere sweater, he had in mind the moment in Lolita when Charlotte Haze, speaking to her wayward daughter on the telephone (the nymphet having been exiled for the summer to Camp Climax), querulously echoes this suspicious news: “You lost your new sweater?… In the woods?”

Such details reveal yet another crucial similarity between the simian and human worlds of 2001. For all the naturalness of their state before the monolith, we never see the apes attempting sex, although we see them trying to find food, to get some sleep, to fight their enemies. That gap in Kubrick’s overview of their condition is surely not a consequence of prudishness (no longer a big problem by the mid-60s), but would appear deliberate – a negative revelation of the thorough harshness of the simians’ existence. The apes are simply too hungry, and too scared, to be thinking about sex, which would presumably occur among them only intermittently, in nervous one-shot bursts – much as in the world of Doctor Floyd, where everyone is much too busy for anything other than a quick bang now and then, and where there’s not a decent place to do it anyway, just as there wasn’t at ‘the dawn of man’.

Afloat in the ‘free world’

Doctor Floyd’s deprivation is not merely genital, however. If, in his asexual state, he is no worse off than his simian forebears, in his continuous singleness he is far more deprived than they. For all their misery, those creatures had at least the warmth and nearness of one another – huddling in the night, there was for them at least that palpable and vivid solace. For that bond – too basic even to be called ‘love’ – there can be no substitute, nor can it be transcended: “There are very few things in this world that have an unquestionable importance in and of themselves and are not susceptible to debate and rational argument, but the family is one of them,” Kubrick once said. If man “is going to stay sane throughout [his] voyage, he must have someone to care about, something that is more important than himself.”

Sacked out on the shuttle, Doctor Floyd is the sole passenger aboard that special flight: literally a sign of his status and the importance of his mission, yet the image conveys not prominence but isolation. The man in the chair has only empty chairs around him, with no company other than the tottering stewardess who briefly comes to grab his pen and, on the television screen before him, another faceless couple in another smart conveyance, the two engaging in some mute love-chat (Doctor Floyd is wearing headphones) while the viewer sleeps and the living woman comes and goes. Here too the machine appears to have absorbed the very longings of the personnel who seemingly control it – for even those two mannequins, jabbering theatrically at each other’s faces, have more in common with the huddling apes than does Doctor Floyd or any of his colleagues.

Whereas the apes had feared and fed together, here everyone is on the job alone. Efficient service to the state requires that parents and children, wives and husbands all stay away from one another, sometimes forever, the separation vaguely eased, or merely veiled, by the compensatory glimpses now and then available (at great expense) by telephone. For this professional class, the family is no sturdier within the ‘free world’ than it is under Soviet domination. “He’s been doing some underwater research in the Baltics, so, uh, I’m afraid we don’t get a chance to see very much of each other these days!” laughs the Russian scientist Irina, a little ruefully, when Floyd asks after her husband. Although (the unseen) Mrs Floyd is, by contrast, still a wife and mother first and foremost, with Hey wood the only wage slave in the family, their all-American household is just as atomised as the oppressed Irina’s. As we learn from Floyd’s perfunctory phone chat with his daughter (“Squirt”, he calls her), the members of his upscale menage are all off doing exactly the same things that the apes had done millennia earlier, although, again, the simians did those things collectively, whereas Floyd’s ‘home’ is merely one more empty module. Mrs Floyd, Squirt tells her father, is “gone to shopping” (charged, like Mrs Moon-Watcher, with the feeding of her young), while Floyd himself, of course, is very far away, at work (squaring off against the nation’s foes, as Moon-Watcher had done). Meanwhile, “Rachel”, the woman hired to mind their daughter in their absence, is “gone to the bathroom” (that primal business having long since been relegated to its own spotless cell), and Squirt herself, she says, is “playing” (just as the little monkeys had been doing, except that Squirt – like her father – is all alone).

Every human need is thus indirectly and laboriously served by a vast complex of arrangements – material, social, psychological – that not only takes up everybody’s time, but also takes us all away from one another, even as it seems to keep us all “communicating”. In the ad-like tableau of Doctor Floyd’s brief conversation with the television image of his little girl, there is a poignancy that he cannot perceive, any more than he can grasp the value of his coming home, in person, for her birthday party. “I’m very sorry about it, but I can’t,” he tells her evenly. “I’m gonna send you a very nice present, though.” In offering her a gift to compensate for his being away, Doctor Floyd betrays the same managerial approach to family relations that enables him to carry on, with his usual equanimity, this whole disembodied conversation in the first place; as far as he’s concerned, that “very nice present” will make up completely for his absence, just as his mere image on the family telescreen ought to be the same thing as his being there. She, however, still appreciates the difference. When he asks what present she would like, with a child’s acuity she names the only thing that might produce him for her, since it seems to be the sole means whereby he checks in at home: “A telephone”.

For all its underlying sadness, the scene is fraught with absurdist comedy: for that telephone is inescapable. It is not just the bright tool through which the family ‘communicates’ but also the very content of that ‘communication’. Here the medium is indeed the message – and there’s nothing to it. “Listen, sweetheart,” says the father, having changed the subject, or so he thinks. “I want you to tell Mummy something for me. Will you remember?” “Yes.” “Tell Mummy that I telephoned. Okay?” “Yes.” “And that I’ll try to telephone again tomorrow. Now will you tell her that?”

The sense of profound emptiness arising from that Pinteresque exchange persists throughout the film, but – once the story shifts to the Discovery – in a tone less satiric, more elegiac. The mood now becomes deeply melancholy, as the two astronauts – a pair identical and yet dissociated, like a man and his reflection – eat and sleep and exercise in absolute apartness, both from one another and from all humankind, each one as perfectly shut off within his own routine and within that mammoth twinkling orb as any of their three refrigerated crew-mates. Aboard that sad craft, every seeming dialogue – save one – is in fact a solitudinous encounter with the Mechanism: either a one-way transmission from earth, belatedly and passively received, or a ‘communication’ pre-recorded, or a sinister audience with the soft-spoken HAL, who, it seems, is always on the look-out for ‘his’ chance to eliminate, once and for all, what Dr Strangelove calls “unnecessary human meddling”. That opportunity arises when the astronauts finally sit down, in private (or so they think), and for once talk face-to-face: an actual conversation, independent of technology and therefore a regressive move that HAL appears to punish, fittingly, by disconnecting his entire human crew – one sent careering helpless through the deeps, the three “sleeping beauties” each neatly “terminated” in his separate coffin, and the last denied re-admittance to the relative warmth and safety of the mothership. Thus HAL fulfils the paradoxical dynamic of the telephone: seeming to keep everyone ‘in touch’, yet finally cutting everybody off.

Too busy for erotic pleasure, as the apes had been too wretched for it, and much lonelier than those primal ancestors, Doctor Floyd is also much less sensitive than they – a being incapable of wonder, as opposed to the wildeyed monkey-men. This human incapacity becomes apparent as the scientist very slowly, very calmly strokes – once (and with his whole body in its plastic glove) – the black lustrous surface of the monolith, thereby both repeating and inverting the abject obeisances of his astounded forebears, crouched and screaming at its solid base and touching at its face again and again, hands jerking back repeatedly in terror at its strangeness. The same profound insensitivity is already apparent in that first satiric tableau of the unconscious scientist, who in his (surely dreamless) slumber is as indifferent to the great sublimity around him as the tense simians were heartened by its distant lights and stirred by its expanses. Whereas the most adventurous among them might sometimes Look beyond their own familiar niche (as Clarke’s epithet “Moon-Watcher” implies), those now in charge take that ‘beyond’ for granted, watching nothing but the little television screens before them.

On the phone to Squirt, Doctor Floyd pays no attention to the great home planet wheeling weirdly in the background, just outside the window. Here, as everywhere in 2001, the cool man-made apparatus has lulled its passengers into a necessary unawareness of the infinite, keeping them equilibrated, calm, their heads and stomachs filled, in order to ensure that they stay poised to keep the apparatus, and themselves, on the usual blind belligerent course. Thus boxed in, they calculate, kiss ass, crack feeble jokes about the lousy food – and never think to glance outside. As the moon bus glides above the spectral crags and gullies of the lunar night, and seems to glide on past the low and ponderous pale-blue earth, three-quarters full, the atmosphere sings eerily, exquisitely, in dissonant and breathless ululation. That is until the point of view shifts into the bus completely, with a dizzying hand-held shot that slowly takes us back from the red-lit cockpit, back into the blue-lit cabin, where one of Doctor Floyd’s subordinates first fetches a big bulky ice-blue ‘refreshment’ carrier (himself in a bulky ice-blue spacesuit), then heaves it slowly back to where Doctor Floyd (likewise besuited) sits in regal solitude, perusing documents, with Halvorsen, his second-in-command, attending him (and dressed the same). As that shot settles us well into this snug artificial space, the atonal shrilling of the quasi-angels gradually gives way to the tranquillising beeps and soporific whoosh of the smart bus itself, and to the (necessarily) stupid conversation of its passengers.

Within that ultimate cocoon, those wry little men are disinclined to think on what had come before them, or on what might lie ahead of them, but concentrate instead on their own tribal enterprise, and on their own careers (and, at some length, on those sandwiches), trading bluff banalities as to the mystery awaiting them. “Heh heh. Don’t suppose you have any idea what the damn thing is?” “Heh heh. Wish to hell we did. Heh heh.” Such complacency endures until their instrument, the hapless ‘Bowman,’ is yanked out of their cloistral world of white and goes on his wild psychedelic ride “beyond the infinite”, ending up immured again, but only temporarily – and in a state promising some sort of deliverance from the human fix. At first shattered unto madness, as opposed to the others’ blank composure, and then quickly wrinkled, turning white, as opposed to their uniform boyish smoothness, he finally, from his sudden death bed, reaches up and out towards, then merges with, the great dark monolith, thereby undergoing an ambiguous ‘rebirth’.

Lonely at the top

In 1968 the ‘futuristic’ world Kubrick satirised so thoroughly was not, despite the title, some 30 years away. The changes the film foretold were imminent. Within a decade 2001 was already getting hard to see – and not just because ever fewer theatre managers would book it, but because its vision was starting to seem ever less fanciful and ever more naturalistic. In other words, the world that Kubrick could confidently satirise in 1968, looking at it – as an artist must – from a standpoint well outside it, would soon begin to look so much like the world that the delighted mass response of the late 60s would soon give way to reactions cooler and less comprehending. Now viewers were less likely to feel “so impressed”, so “awed”, and more likely to reply, “So what?” – an indication not of the film’s datedness, but of its prescience.

Within a decade of the film’s release, the crucial spaces of the human world – where people live, work, shop, see movies, talk about them – had begun increasingly to look like the arid mobile spaces where the people ‘live’ in 2001. The long white sloping corridors of the space station with their sealed windows and fluorescent glare, their hard red contoured chairs and small white plastic tables, now no longer anticipate some eventual trend in architecture but reflect, as if directly, the unilinear vistas within countless shopping malls (which began to dominate the American landscape – urban and suburban – in the late 70s), ‘business parks’ and corporate headquarters. Likewise, those over-bright, hermetic confines, so carefully designed to withstand both the great external vacuum and any possible internal breaches of ‘security’, now seem oddly imitative of the recent condos, hospitals, hotels and dormitories of the west, all of them likewise built against the threats of nature and the human swarm. That implicit militarisation of our various homes has surely had profound and imperceptible effects on us – effects that might pertain to the recent invisibility of 2001. The film’s first undergraduate devotees were also members of a student generation likely to assemble in protest – a social tendency soon systematically disabled by the sponsors and practitioners of the New Brutalism, which, as applied specifically to campus architecture in the 70s, was intended to pre-empt further insurrection by eliminating all common spaces, openable windows and any other points or means of mass agitation or discussion. Thus today’s student audience, taught and housed within the quieter system, would tend much less to sense, looking at Floyd’s hushed domain, that there’s something wrong with it.

If it were re-released today, 2001 would be diminished by the multiplex not just because of the smaller screen and poor acoustics, but because the very setting would implicitly subvert the film’s subversive vision. Even if it were brought back to some quaint old movie palace, however, 2001 still could not exert its original satiric impact because the mediated ‘future’ it envisions is now ‘our’ present, and therefore unremarkable: a development not merely architectural but ideological. The world of Doctor Floyd (like the new dorm, mall or hospital) is a world absolutely managed – the force controlling it discreetly advertised by the US flag with which the scientist often shares the frame throughout his “excellent speech” at Clavius, and also by the corporate logos – ‘Hilton’, ‘Howard Johnson’, ‘Bell’ – that appear throughout the space station. In 1968, the prospect of such total management seemed sinister – a patent circumvention of democracy. Today, within the ever-growing ‘private’ sphere the movie adumbrates, that ‘prospect’ seems completely natural.

Whereas audiences back then would often giggle (uneasily, perhaps) at the sight of, say, ‘Howard Johnson’ up there in the heavens, today’s viewers would fail to see the joke, or any problem, now that the corporate logo appears en masse not just wherever films might show, but also in the films themselves, whose atmosphere nowadays is peculiarly hospitable to the costly ensign of the big brand name. We might discern the all-important difference between what was and what now is by comparing Kubrick’s sardonic use of ‘Bell’ and ‘Hilton’ with the many outright corporate plugs crammed frankly into MGM’s appalling ‘sequel’ 2010, released in 1983. Whereas the (few) plugs in Kubrick’s film were too weird – and the film itself too dark and difficult – to make those corporations any money, in the later film the plugs were so upbeat and unambiguous (the advertisers actually helped out), and there were so many of them, that the whole complex of deals was hailed by advertising mavens as a breakthrough in the commercialisation of cinema. “2010 is a case of how product placements in the movie are becoming a springboard for joint promotions used to market films,” exulted Advertising Age before the film’s release, noting the elaborate plugs for Pan-Am, Sheraton Hotels, Apple Computer, Anheuser-Busch and Omni magazine. (Those outfits evidently liked the insane revisionism of 2010, which ends with the ecstatic news that what those dark monoliths portended all along, in fact, was the emergence in our heavens of a second sun – so that night will never fall on us again!)

As such colossal advertisers have absorbed the culture since the early 70s, they have helped obscure 2001 by celebrating and encouraging the very drives Kubrick satirises. Indeed, the impulse to retreat from nature, to lead a ‘life’ of perfect safety, regularity and order in some exalted high-tech cell, and to stay forever on the job, solacing oneself from time to time with mere images of some beloved other, is – one might argue – the fundamental psychic cause of advertising. So it makes a certain sense that some of Kubrick’s most ironic images should keep popping up uncannily – that is, without the irony – on billboards and television screens, in newspapers and magazines. “AHH. IT’S LONELY AT THE TOP.” Thus TWA and American Express extol the very state that Kubrick questions – the same unconsciousness and isolation, the same complacency, with the advertisement relying on an image strangely similar to Kubrick’s mordant tableau of the flaccid Doctor Floyd. We likewise recall him in glancing at an ad for Continental, which promotes “a big, comfortable electronic sleeper seat with adjustable headrest, footrest and lumbar support; two abreast seating; and a multichannel personal stereo entertainment, system with your own five-inch screen.”

Such come-ons offer the busy manager a range of artificial substitutes for the warmth he’s left behind – as in 2001, where it is not only the “electronic sleeper seat” that is meant as compensation, but, as we have seen, the vivid image of a ‘loved one’ made as if available by Bell. That satiric moment too has been much repeated, and completely neutralised, by advertisers. In a television spot for MCI, a father talks as warmly to his daughter’s image on a telescreen as if the girl herself were there before him (MCI’s point being, of course, that there is no difference). In an ad for Panasonic, Mom’s voice rising from the answering machine, and forming a protective shield between the needy little girl and her strangely droogish ‘brother’, itself seems as protective as Mom herself would be were she only there. Whereas Kubrick’s telephone is an uncanny instrument – like HAL, a means that would itself dictate the end – Bell’s ads deliberately promote the instrument’s displacement of its human users, offering the telephone itself as your closest “friend”.

Thus has the satiric prophecy of 2001 been blunted by its own fulfilment. And yet there is still more to it than these brief speculations would imply. The fatal human tendency to shut oneself off, wall oneself in, has been accelerated since the film’s release, not only by certain architectural trends, nor simply by the great commercial conquest, but – primarily – by the rise, or spread, of television, which has facilitated that great conquest, enabled (and been all the more enabled by) those architectural developments, and which has at once vindicated Kubrick’s satire and practically extinguished it.

Frankly “wide-eyed”, “thrilled”, “so very lifted” and blithely venturing impassioned and detailed interpretations (with many a bold foray into numerology), Kubrick’s ardent first fans seem as anachronistic today as, say, the earnest maiden devotees of the Pre- Raphaelites, now that television has universalised a spectatorial attitude so much more jaded and less demanding. The vision that so awed those first several million viewers is now more likely to leave audiences cold – or to get them snickering, since a certain blasé knowingness pervades the global culture of television as fully as a certain blissed-out recklessness prevailed within the original cult of LSD. The apparent high solemnity of Kubrick’s neo-epic – and the immediate recognisability of its most famous bits – would seem now to require the same sophisticated chuckling that so often greets the Mona Lisa, say, or Kane whispering “Rosebud”, or Marion Crane screaming, or any other much-remembered ‘classic’ clip. Even while 2001 was still showing up in theatres, its most vivid touches were already being neutralised by parody – the motif from Strauss’s ‘Zarathustra’ recurring as an automatic joke in numerous commercials (and in Mike Nichols’ Catch-22), the famed match cut inspiring bits among stand-up comics, in Mad magazine and (brilliantly) in Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Today most big releases are immune to parody, since – like mass advertising, countless television shows and virtually every candidate for public office – they come at us already (gently) parodying themselves (and/or their exhausted genre), so as at once to pre-empt any spectatorial ridicule and to solicit the cool viewers’ allegiance by flattering them with an apparent nod to their unprecedented savvy. Every viewer has become a watchful ironist; and in this nervous, jokey atmosphere Kubrick’s genuinely cool and wholly uningratiating film must seem, in spite of its Nietzschean subtext, as archaic and austere (and as hard to follow) as the Latin Mass.

Artificial voices

Yet while television’s most devoted ironists probably could not enjoy the film, in their plight they also prove the chilling prescience of 2001 – for that pastime is just one more technological absorption, sold as a nice cold substitute for the warmth of actual others. On Comedy Central, “the only all-comedy cable channel”, there is a very hot new show called Mystery Science Theater 3000, which features hours and hours of bad old movies, ‘watched’ by a man and his two robots, who, appearing in silhouette along the bottom of the screen as if a row ahead of you, wisecrack throughout the dated spectacle. “A New Thanksgiving tradition,” proclaims a recent ad in TV Guide. “Watching 32 straight hours of a human and his robot cohorts rag on cheesy movies while your relatives argue over the white meat.” Thus those born since the release of Kubrick’s film are jeeringly invited to surrender utterly to the machine. Like Frank Poole playing chess with HAL (and losing), and like Doctor Heywood Floyd, who also thinks he knows it all already, they would approach the future in their chairs, alone, needing no friends, since they have those artificial voices – and the sponsors – ‘there’ to crack the jokes, and to laugh along.

Sight and Sound (v4, #1) 1994, pp.18-25