Most of the sporadic power and sly humor of 2001: Space Odyssey derive from a contrast in scale. On the one hand we have the universe; that takes a pretty big hand. On the other we have man, a recently risen ex-ape in a dinky little rocket ship. Somewhere between earth and Jupiter, though, producer-director Stanley Kubrick gets confused about the proper scale of things himself. His potentially majestic myth about man’s first encounter with a higher life form than his own dwindles into a whimsical space operetta, then frantically inflates itself again for a surreal climax in which the imagery is just obscure enough to be annoying, just precise enough to be banal.

The first of the film’s four movements deals with man’s prehistoric debut. It is as outrageous and entertaining as anything in Planet of the Apes, but much more engrossing. Cutting constantly between real apes and actors (or dancers) in unbelievably convincing anthropoid outfits, Kubrick establishes the fantasy base of his myth with the magical appearance of a monolithic slab in the apes’ midst. They touch it, dance around it, worship it. The sequence ends with a scene in which one of our founding fathers picks up a large bone, beats a rival into ape-steak tartare with it and thus becomes the first animal on earth to use a tool. The man-ape gleefully hurls his tool of war into the air. It becomes a satellite in orbit around the moon. A single dissolve spans four million years.

With nearly equal flair the second movement takes up the story in the nearly present future. Man has made it to the moon and found another shiny slab buried beneath the surface. By this time the species is bright enough to surmise that the slab is some sort of trip-wire device planted by superior beings from Jupiter to warn that earthmen are running loose in the universe. Kubrick’s special effects in this section border on the miraculous—lunar landscapes, spaceship interiors and exteriors that represent a quantum leap in quality over any sci-fi film ever made.

In a lyrical orbital roundelay, a rocket ship from earth takes up the same rotational rate as the space station it will enter. Once again, as in Dr. Strangelove, machines copulate in public places. This time, however, they do it to a Strauss waltz instead of “Try a Little Tenderness”—the smug, invariable, imperturbable swoops of “the Blue Danube” juxtaposed with the silent, indifferent sizzling of the cosmos.

Where Strangelove was a dazzling farce, 2001 bids fair at first to become a fine satire. We see that space has been conquered. We also see it has been commercialized and, within the limits of man’s tiny powers, domesticated. Weightless stewardesses wear weightless smiles, passengers diddle with glorified Automat meals, watch karate on in-flight TV and never once glance out into the void to catch a beam of virgin light from Betelgeuse or Aldebaran.

The third movement begins promisingly, too. America has sent a spaceship to Jupiter. The men at the controls, Keir Dullea and Gary Lockwood, are perfectly deadpan paradigms of your ideal astronaut: scarily smart, hair-raisingly humorless. The computer that runs the ship and talks like an announcer at a lawn-tennis tournament admits to suffering from certain anxieties about the mission (or, more ominously, pretends to suffer from them), but the men are unflappable as a reefed mainsail.

Your own anxieties about 2001 may begin to surface during a scene in which Lockwood trots around his slowly rotating crypt-ship and shadowboxes to keep in shape. He trots and boxes, boxes and trots until he has trotted the plot to a complete halt, and the director’s attempt to show the boredom of interplanetary flight becomes a crashing bore in its own right. Kubrick and his co-writer, Arthur C. Clarke, still have some tricks up their sleeves before Jupiter: pretty op-art designs that flicker cryptically across the face of the instrument display tubes, a witty discussion between Dullea and Lockwood on the computer’s integrity.

But the ship is becalmed for too long, with stately repetitions of earlier special effects, a maddening sound of deep breathing on the sound track, a beautiful but brief walk in space and then a long, long stretch of very shaky comedy-melodrama in which the computer turns on its crew and carries on like an injured party in a homosexual spat. Dullea finally lobotomizes the thing and, in the absence of any plot advancement, this string of faintly familiar computer gags gets laughs. But they are deeply destructive to a film that was poking fun itself, only a few reels ago, at man’s childish preoccupation with technological trivia.

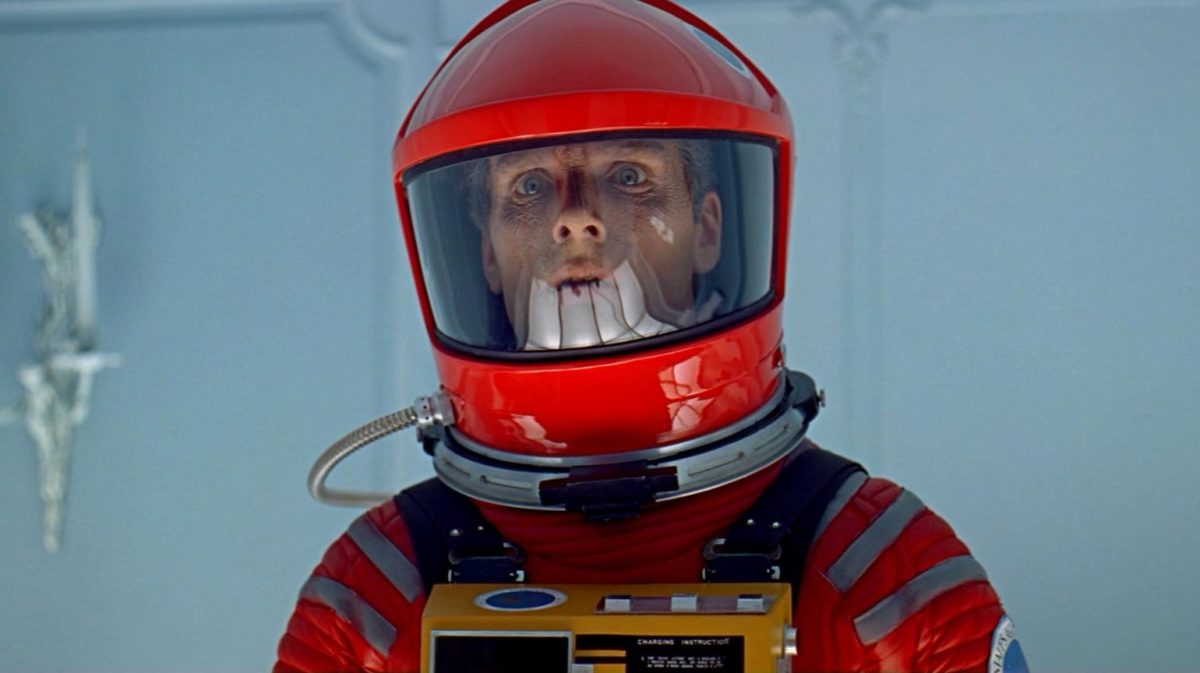

On the outskirts of Jupiter 2001 runs into some interesting abstractions that have been done more interestingly in many more modest underground films that were not shot in seventy-millimeter Super Panavision, then takes a magnificent flight across the face of the planet: mauve and mocha mountains, swirling methane seas and purple skies. But its surreal climax is a wholly inadequate response to the challenge it sets for itself, the revelation of a higher form of life than our own. When Dullea, as the surviving astronaut, climbs out of his space ship he finds it and himself in a Louis XVI hotel suite. Original? Not very. Ray Bradbury did it years ago in a story about men finding an Indiana town on Mars, complete with people singing “Moonlight on the Wabash.”

It is a trap, in a sense, with the victim’s own memories as bait. The nightmare continues, portentously, pretentiously, as Dullea discovers the room’s sole inhabitant to be himself. As he breathes his last breath another slab stands watching at the foot of his deathbed, and when he dies he turns into a cute little embryo Adam, staring into space from his womb. So the end is but the beginning, the last shall be first, and so on and so forth. But what was the slab? That’s for Kubrick and Clarke to know and us to find out. Maybe God, or pure intelligence, maybe a Jovian as we perceive him with our primitive eyes and ears. Maybe it was a Jovian undertaker. Maybe it was a nephew of the New York Hilton.

Newsweek, April 15, 1968