by Burke Wilkinson

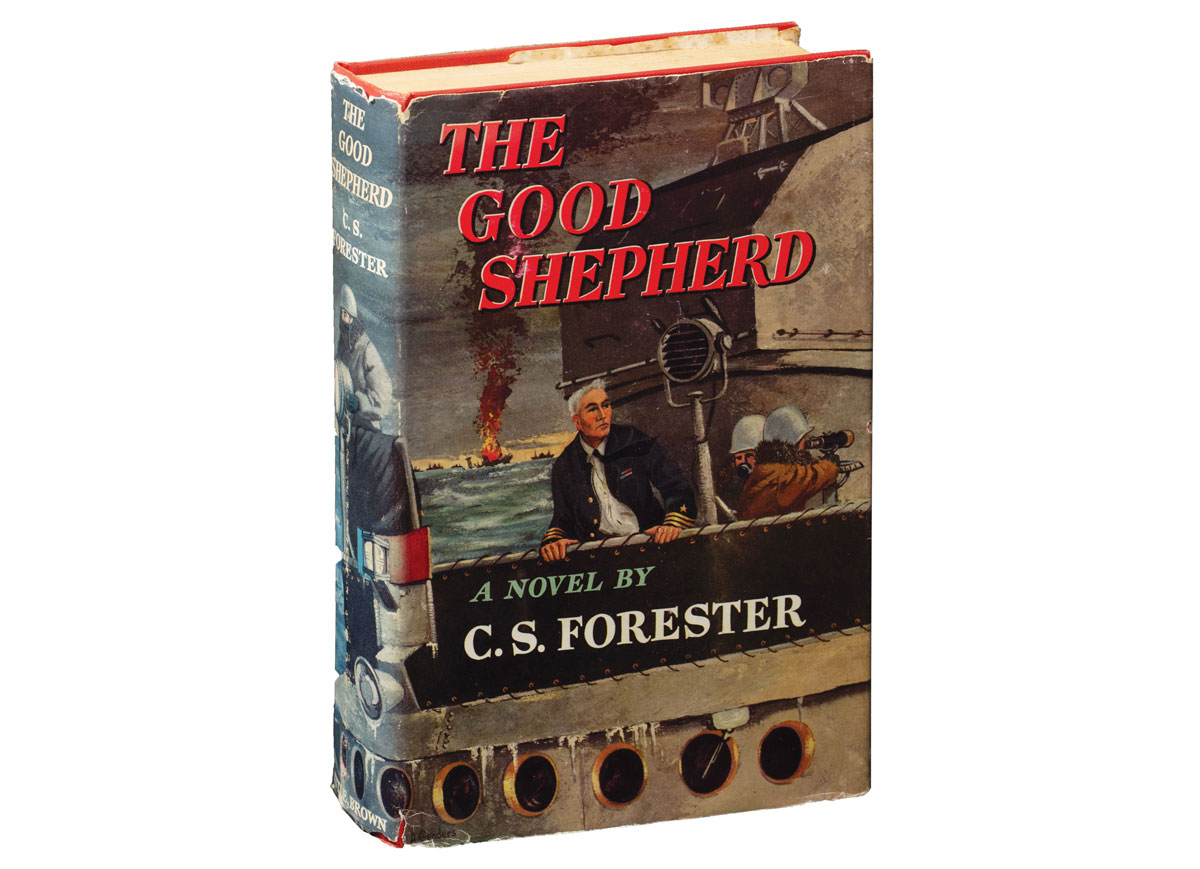

C. S. Forester has two skills which are admirably blended in “The Good Shepherd,” a first-rate novel of World War II. He is able to make us identify ourselves with the tensions and the loneliness of man, this time a man in command of many men. He also is able to make us see and hear and feel action, especially when writing of ships and the sea, so vividly that a powerful sense of participation is inevitable.

The gift of enforcing on the reader this sense of identification and participation explains the enduring fascination of Forester’s most celebrated creation—Captain Horatio Homblower. Hornblower’s all-too-human doubts and fear, beneath the resolute exterior, communicate themselves to us even as we project ourselves into his exploits. But even the fine Homblowers do not match .the present achievement. “The Good Shepherd” is the story of forty-eight desperate hours in the life of a North Atlantic convoy. The time is early in the war, before improved sonar and hunter-killer teams turned the tide against the U- boats. Commander of the escort vessels (Comescort) by accident of rank is Comdr. George Krause, U.S.N. To protect the thirty-seven merchantmen under a retired British admiral (Comconvoy), Krause has exactly four ships. [. . .] Twelve escorts would be needed to do the job with any real safety.

The story of the novel is Krause’s: the action revolves around him, and outward from him. All the other Krauses that have gone before are important only in their effect on Krause, the defender of his charges, and Krause, the killer of the enemy which seeks to destroy them. [. . .] Krause is the good shepherd of his lumbering flock. With him we shall not want for a high and glittering excitement. [. . .]

In writing about “The Good Shepherd” it is almost impossible not to fall into Biblical cadence. Running through it like the voices of a fugue are quotations from the Bible which underline the action. [. . .]

This device, irritating at first, soon achieves its purpose of heightening our sense of identification with the God-fearing Krause. Again and again we come back to the man. Krause, for all his sternness, has his moments of doubt and fear. Like many men in whom the power of command is strong, he can still sometimes envy those who have only to obey, even to the death. He is sharply aware of the place where science ends and the human factor begins. [. . .]

The reminder that machines of destruction can never be the master of man is always valid, and particularly so today, but the basic appeal of the story is to emotion, not reason. The emotions it inspires are simple, elemental: love of the good shepherd and the father-protector, hatred of the feathering periscope that is evil personified, fear of oil and flame and ice- green water.

The acclaim that has already greeted the new Forester is an earnest of success to come. [. . .] The truth is that “The Good Shepherd’’ is so good that the tendency in a time of minor talent is to call it a great novel. This it is not. Forester starts—in his compression and use of exact detail—where most writers leave off. But he ends just short of the titans of fiction. No other character save Krause has more than one dimension. The rest are voices over intercoms, brief glimpses like star shells. It is a story of tension, not of dimension, and it was so intended.

But in Forester’s chosen field, and when his talents for creating a sense of participation and of identification are in top gear, he has no master and few peers.

SOURCE: Burke Wilkinson, “With the Wolf Pack Dead Ahead,” in The New York Times Book Review, March 27. 1955 [Extracts]