Luciano Canfora’s new book shows how war was used by ancient societies to secure resources.

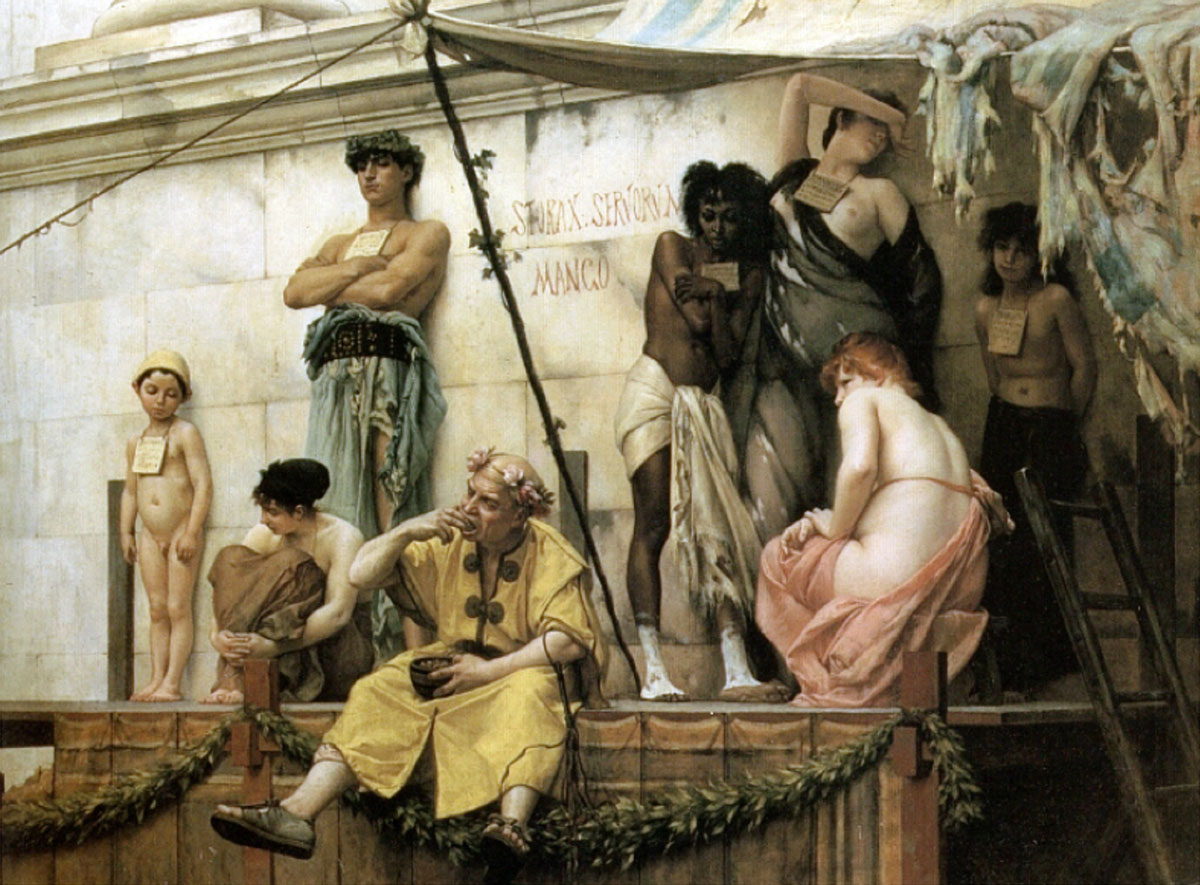

Ancient societies were unequivocally characterized by the institution of slavery. This assertion transcends any remnants of paleo-Marxism that might seek to diminish the accomplishments of the revered Greco-Roman culture; rather, it stands as an extensively substantiated and challenging-to-dispute historical reality.

The foundational poem of Western civilization, the Iliad, commences with the contentious dispute between two malefactors, Achilles and Agamemnon, vying for the right to possess and exploit a captive slave, a war trophy. The Roman economy, flourishing miraculously, owed much to the labor of foreigners forcibly taken as prisoners of war and transported to Italy for cultivation in the agricultural enterprises of the affluent, often proto-industrial ventures dealing in oil, wine, and other tradable commodities.

The influx of foreign slaves not only incited various slave revolts, ardently suppressed by Rome, but also posed significant challenges for small Italian farmers who, having lost their lands, faced unemployment. The rebels were destined for ergastula, and in cases of major uprisings, crucifixions awaited, exemplified by the fate of Spartacus and his companions along the Appian Way. Augustus, in his boastful transformation of Rome from a brick city to one of marble, omitted the source of his wealth—the gold acquired through the much-criticized Cleopatra.

Accounts from Roman historians, such as Tacitus, of Gallic origin, shed light on how the conquered Gauls, subdued by Caesar, perceived Rome. Even Roman poets and philosophers, acknowledging the nexus between war, slavery, and wealth, occasionally voiced scathing self-criticism. Lucretius, for instance, posited that the life of primitive humans was preferable, despite the risk of wild animal attacks, as it spared them from sending thousands of young men to die in a single day—a sentiment resonating with the Epicurean desire for a life of fewer necessities, a true “happy degrowth.”

Even Horace, the bard of the Augustan regime, lamented the destruction of an entire generation in civil wars and foresaw the arrival of barbarians to raze Rome. Seneca, in his Letters to Lucilius, pondered the meaning of slavery, noting that even the cream of Roman youth, born to rule the empire, could become slaves in the event of defeat.

In his recent work, Guerra e schiavi in Grecia e a Roma. Il modo di produzione bellico [War and Slaves in Greece and Rome: The Wartime Mode of Production]—published by Sellerio)—Italian professor Luciano Canfora follows in the footsteps of masterpieces like The Ancient Economy by Moses I. Finley. Canfora’s compelling narrative encourages a clearer examination of the intricate connections between war, slavery, and economics in the ancient world.

The Greek miracle and Rome’s unparalleled growth derived impetus from the conquest of other lands, resulting in the pillage of goods, imposition of fines and tributes, and deportation of slaves for labor. Rome perfected this strategy, strategically targeting the wealthiest regions and key trade routes rather than mere lust for power.

The predatory disposition of Rome is evident in its treatment of foreign temples, often functioning as large banks in the ancient world. The coveted Temple of Jerusalem, collecting annual offerings from Jews worldwide, became a victim of plunder and destruction, accompanied by the genocide of a million people and the deportation of a hundred thousand Jews to Italy under Titus, ironically hailed by contemporary historians as “the delight of humanity.”

However, with the cessation of Rome’s conquests, the wartime mode of production faltered. Emperors, striving to defend borders and maintain armies, exacerbated the tax burden to unsustainable levels. This precipitated the “silent fall” of the empire, as described by Arnaldo Momigliano, and a reversal of fortunes, transforming the once-mighty Romans from conquerors into slaves.

Luciano Canfora, Guerra e schiavi in Grecia e a Roma. Il modo di produzione bellico, Sellerio, pp. 110, €13

December 3, 2023