Introduction

by Frederic Raphael

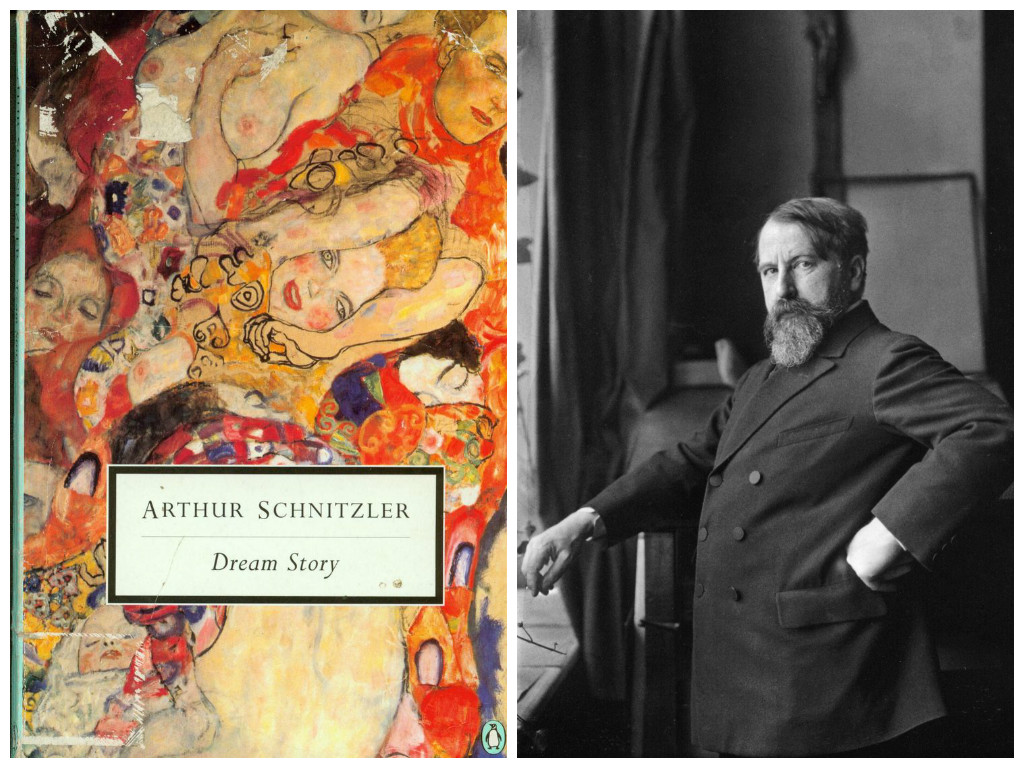

By the time Arthur Schnitzler was born in Vienna in 1862, Franz-Josef had been on the throne of Austria-Hungary for ten years. The emperor did not die until 1916. The dual kingdom survived only two more years before being dismantled by the Treaty of Versailles. Although, when he died in 1931, Schnitzler had survived Franz-Josef by fifteen years, his creative life was determined by the protracted twilight of an empire which lost its hegemony, and its nerve, when he was four years old.

In 1866, Bismarck’s Prussia destroyed Austro-Hungary’s bravely incompetent army at Sadowa. The effect of that defeat on the Viennese psyche cannot be exactly assessed. Austria had already suffered preliminary humiliation by the French, under Louis-Napoleon, but Sadowa confirmed that she would never again be a major player in the world’s game. Yet conscious acceptance of Austria’s vanished supremacy was repressed by the brilliance and brio of its social and artistic life. Who can be surprised that Adler’s ‘discovery’ of the inferiority complex, and of compensating assertiveness, was made in a society traumatized by dazzling decline? It was as if the city which spawned Arthur Schnitzler and Sigmund Freud feared to awake from its tuneful dreams to prosaic reality. By a pretty, untranslatable pun, Traum (the German for a dream) and trauma were almost indistinguishable in the Vienna which was at home to both.

Arthur Schnitzler’s father (whose family name had been Zimmermann) had come to Vienna from Hungary before the disasters which fostered Austro-Hungary’s crisis of identity. After them, Vienna soon became the forcing ground for a variety of diagnoses and putative cures: psychological for neurotic individuals; political or nationalistic for the fractious elements of a disintegrating empire. On the surface, however, it was business, and pleasure, as usual.

Medicine offered Schnitzler père a stable, respectable career. When he specialized, as a laryngologist, he became rich and comfortable. For a long while, assimilation to Christian society seemed a feasible destiny for the Jewish elite. In the first decade after Arthur’s birth, professional and social life in Vienna showed few signs of the aggressive anti-Semitism which was to be marked – and politically rewarding – long before the end of the century. Only in the 1890s was the odiously affable Karl Lueger elected mayor of Vienna on an overtly anti-Semitic ticket, although individual Jews were indeed some of his best friends.

Unlike many successful families (the Wittgensteins were a prime example), the Schnitzlers did not renounce Judaism. Their observation of High Days and Holy Days was, however, no more than pious politeness. Respect for religion was a gesture to please the older generation; young Schnitzler enjoyed fasting not least because it sharpened his appetite for the delicacies which greeted its end. Hypocrisy could scarcely be distinguished from good manners.

Medical science was, in a sense, an ecumenical religion. The common anatomy of mankind assimilated Jews to Gentiles. What reason was there to feel inferior? As Shylock had pointed out, Jews and Christians bleed under identical circumstances. In the dissecting room, as Schnitzler recalls, students confronted the common humanity of the cadaver:

. . . like my colleagues, I tended to exaggerate … my indifference to the human creature become thing … I never went as far in my cynicism as those who considered it something to be proud of when they munched roasted chestnuts … at the dissecting table. At the head of the bed on which the dead man lies, even if the man who has just breathed his last is unknown to you, stands Death, still a grandiose ghostly apparition . . . He stalks like a pedantic schoolmaster whom the student thinks he can mock. And only in infrequent moments, when the corpse apes the living man he once was in some grotesque motion . . . does the composed, even the frivolous man experience a feeling of embarrassment or fear.

In Dream Story, Fridolin has similar reactions after his visit to the morgue, where the deadness of a dead woman does not prevent her from seeming to reach out to embrace the living.

Despite early dismay at the realization of his own mortality, Schnitzler observed with clinical equanimity what was physiologically common to all men. Freud declared our psychological anatomy to be no less universal. Medicine and science, like the arts, convinced talented Jews that they could and should look to a more modern allegiance than Judaism; logically speaking, only atavistic prejudice stood between them and citizenship in the civilized world. At the same time, Freud and Schnitzler saw that what was reasonable was also unreliable. Who could depend on the fundamental decency of a society where, beneath the elegant surface, irrational motives made nonsense of constancy and a comedy of morals?

Schnitzler begins his fragment of autobiography – My Youth in Vienna — by telling us

I was born on the 15th of May 1862, in Vienna, on the Praterstrasse … on the third floor of a house adjacent to the Hôtel de l’Europe. A few hours later, as my father liked to tell so often, I lay a while on his writing desk . . . the incident gave rise to many a facetious prophecy concerning my career as a writer, a prediction my father was to see fulfilled only in its modest beginnings and not with undivided joy.

The Oedipal theme which was to become central to Sigmund Freud’s theory of human behaviour is noticeable at once. Schnitzler suggests both that his father told his story repeatedly and that he regarded his son’s fame without enthusiasm. Despite his youthful zeal for scandalous themes and rakish behaviour, Arthur never wholly rebelled against the paternal model, though he did not practise medicine regularly once his plays were fashionable. For a time, however, he did edit a medical journal which his father had founded. His 1912 play, Professor Bernhardi, shows thorough knowledge of the treacherous politics of the Viennese medical world. The success (and hence the menace) of Jewish doctors led to increasing, often devious, discrimination against them. Roman Catholic tradition had fostered an animosity which its hierarchy did nothing to discourage.

Freud’s determination to make a name for himself, outside conventional medicine, testifies to apprehension of the impediments which Jews could expect if their careers took routine paths. At the same time as advertising his retreat to a solitary wilderness, Freud craved recognition by the very establishment whose ill-will he feared: by recruiting the Gentile Carl Gustav Jung to the psychoanalytic camp, he sought to establish the scientific and un- Semitic character of his challenging theories. He was not the only Jew to be torn between the desire for independence from the scornful majority and an appetite for its applause. Otto Weinmger, Gustav Mahler, Hermann Broch, Karl Kraus, Stefan Zweig, no less than half- or crypto-Jews such as Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Ludwig Wittgenstein, were but the most renowned of many who could not renounce a society which might, at any time, turn spitefully against them.

Schnitzler neither denied his Jewishness nor asserted it. Denial was demeaning; assertion led to self-deluding vanity. The doubleness of their identity sometimes created inescapable (and not infrequently suicidal) strains in Austrian Jews, but Schnitzler’s dexterity with dialogue- which served him so well in the theatre – and his light touch can be seen as a witty strategy which gave him the nervous freedom both to be and not to be as other men. All his writing life, he observed the Jewish condition with an involved aloofness which parallels the cold eye which Freud brought – or presumed that he brought — to his self-analysis. As Schnitzler observed,

You [a Jew] had the choice of being counted as insensitive, shy and suffering from feelings from persecution. And even if you managed somehow to conduct yourself so that nothing showed, it was impossible to remain completely untouched; as for instance a person may not remain unconcerned whose skin has been anaesthetized but who has to watch, with his eyes open, how it is scratched by an unclean knife, even cut until the blood flows.

Schnitzler responded to the Jewish condition without affecting to provide a solution. His fame as a writer (he won the ‘Oscar’ of the Viennese theatre, the Grillparzer Prize, in 1908) immunized him from artistic frustration; it did not spare him vicious critical attacks. He was accused of being a Hungarian upstart or, worse, a corrupting outsider (his famous Reigen – later filmed as La Ronde and ‘improved’ recently by David Hare in The Blue Room — was banned as immoral for twenty-five years).

Medical familiarity with syphilis as a source of dementia punctuated levity with horror. A keen, not to say addictive, pursuer of sexual quarry, Schnitzler was not immune to squeamishness. Reluctance to take all his opportunities was a matter less of moral refinement than of clinical caution: his father had shown the adolescent Arthur lurid pictures of the effects of venereal infection. He mocks his own juvenile attempts to redeem fallen women:

While the pretty young tow-headed Venus reclined naked on the divan, I leaned against the window frame, still fully dressed in my boyishly cut suit, my straw hat and cane in my hands, and appealed to the conscience of my beauty, who was bored and amused at the same time, and had certainly expected better entertainment from the sixteen-year- old customer who was urging her to find a more decent and promising profession … I tried to emphasize what I had to say by reading some appropriate passages from a book I had brought along for the purpose … I left her with two gulden for which I had my mother to thank. She had given them to me after I had declared that I simply had to have the Gindely Outline of World History.

The hero of Dream Story is no youth, but he is similarly affected by the apparent innocence of a young prostitute. All his life, Schnitzler’s imagination dwelt on the habits and inhabitants of fin de siècle Vienna. His touch was light, and remorseless. He was certainly no more indulgent to Jews than to anyone else. One of his few full-length novels, Der Weg ins Freie, or The Road to the Open, was published in 1908 and dealt, with his usual scepticism, with the various answers to what was called the Jewish question. It was typical of his clinical egotism that he refused to be gulled by any panacea, including Zionism.

Schnitzler’s friend Theodor Herzl, his elder by two years, failed to achieve equal success as a writer, though he did become a fluent journalist. It is usually alleged that Herzl wrote his Zionist manifesto, Der Judenstaat, as a result of the endemic, and epidemic, anti-Semitism which he observed when he was in Paris, covering the Dreyfus trials for his Viennese newspaper. In fact, no less plausible reasons for the creation of a Jewish state were to be found, in abundance, at home.

Earlier, like many bright young Jews impatient of the ghetto mentality, the student Herzl had seen his future identity as closely linked with Germanism. He was a keen member of a Verbindung until the ‘Alemannic’ Association decided to ‘bounce’ its Jewish members. Only then, as Robert Wistrich remarks, in his Jews of Vienna in the Age of Franz Joseph, was Herzl’s ‘allegiance to the semi-feudal values and German nationalism of the Austrian Burschenschaften . . . shaken to the roots’. He had previously enjoyed ‘the romantic ritual of the Teutonic student . . . the sporting of glamorous swords, coloured caps, and ribbons’. On the rebound, Herzl came to advocate a sort of Jewish Austria in Palestine. When he invited Schnitzler to imagine his plays being performed in Jerusalem, the reply was dismissively terse: ‘But in what language?’ Schnitzler belongs inextricably to mittel-Europa. He could not imagine himself, or his work, without them. ‘En Europe,’ E. M. Cioran was to say, ‘le bonheur finit à Vienne’ (‘Happiness ends at Vienna’). Does this mean that beyond Vienna there is no happiness or that in Vienna there is none? Cioran offers a typically ambiguous tribute to a city where the dyarchy of love and death shadowed the dual monarchy of the ageing Franz-Josef.

The writer of fiction is free to invest himself in all his characters, and in no single one of them. Arthur Schnitzler accepted, and maybe somewhat gloried in, being doubly alienated: as a Jew and a doctor, he was resigned to being marked off from the society he amused and adorned. Why then should he try to be as other men were? If the Jew was an object of suspicion, he could return the sour compliment by regarding Vienna with an unblinking eye and listening with an accurate ear. The unveiling of unacknowledged (and often unsavoury) motives was typical of Austro-Marxism, of logical positivism, of psychoanalysis and of Schnitzler, whom Freud saluted as his ‘alter ego’. Freud said that Schnitzler was an artist who had come by instinct and narcissistic intuition to conclusions about the primacy of the erotic which Freud himself claimed that he had discovered by the scientific observation of others.

The ‘hero’ of Traumnovelle, or Dream Story, is a doctor who, in obvious ways, resembles his author. He neither indulges nor spares himself in the trenchancy of the notes on his own case. Fridolin’s adventure is not, we may assume, a transcription of his author’s own adventures, or dreams (it is too shapely and too artful), but in his autobiography Schnitzler wrote that his writings were an intrinsic element of his existence: ‘even if the story relating to some of them may not belong to literary history, it certainly does belong in the story of my life’.

The tone and attitudes to be found in Dream Story are certainly true to the spirit both of Schnitzler’s personal life and of decadent Vienna. Despite the fact that the story was not published till 1926 (though it may well have existed in Schnitzler’s mind, or his files, before that), it shows no signs of taking place in a post-1918, post- Hapsburg world. Its characters and atmosphere are as dated as its traffic: there are no cars or buses, no hint of Austria’s final reduction to a post-imperial republic.

When Fridolin is confronted by a band of rowdy students, one of whom seems deliberately to insult him by bumping into him, the smart louts are said to be members of just such an ‘Alemannic’ club as bounced Theodor Herzl from membership back in the 1880s. Fridolin is not declared to be a Jew, but his feelings of cowardice, for failing to challenge his aggressor, echo the uneasiness of Austrian Jews in the face of Gentile provocation; Freud, for famous instance, never forgave his father for failing to stand up to a bully who knocked his hat into the gutter. Jews were said to be natural cowards and not worthy of Aryan steel. Robert Wistrich, however, suggests that the reason for bouncing Jews from student fraternities and for refusing them ‘satisfaction’ was that, in fear of provocation, a good many Jews had become so expert at swordsmanship that they were embarrassingly likely to win in a duel.

Although no coward, Schnitzler disdained to fight. He satirized the absurdity of the point of honour and the double standards of Viennese ‘morality’ in a play (Das Ferne Land) in which a philandering husband challenges and kills his wife’s sole lover, thus extinguishing a young life and bringing incurable bitterness to his marriage, simply because vanity requires it.

The Jewish question is only lightly touched upon in Dream Story. The Bohemian wanderer, Nachtigall, is said to have had a quarrel with a bank-manager in whose house he played and sang a raucously indecent song. His host, ‘though himself a Jew… hissed a Jewish insult in his face’, after which ‘his career in the better houses of the city seemed to close for ever’. This Jewish anti-Semitism (by no means the same as self-hatred) confirms Schnitzler’s melancholy observation of ‘the eternal truth that no Jew has any real respect for his fellow Jew, never’. He concedes that he sometimes says more about Jews than may seem ‘in good taste, or necessary or just’. He hoped that in some happier future it would become impossible to imagine why the issue was so important to him. He died two years before Hitler’s access to power. Subsequent events proved that even his genius for conjuring up nightmares was incapable of conceiving the horrors in store.

Although Fridolin does not endure the same insult as Nachtigall, there is, I suspect, cunning in Schnitzler’s using it to ‘trail’ what happens when his hero goes to the erotic house party to which Nachtigall lures him. If he is not abused or revealed as a Jew, his unmasking by the in-group and his summary eviction from the revels surely resemble the kind of jeering ostracism of which any arriviste might at any moment be the victim. Fridolin’s ‘rescue’ by the beautiful woman is both romantic and degrading: when she takes upon herself the consequences of his transgression, she becomes, in a sense, more manly than he is allowed, or dares, to be. This, as well as desire, is one of the motives for his restless need to find her again.

It may be reading too much into a good tale to remark that Fridolin’s monk’s habit (though banal enough for a fancy-dress occasion) means that, in disguise, he has chosen to cross the line between Jews and Catholics; it is, one might argue, justice that he is discovered. The paedophiles disguised as ‘vehmic judges’, whom he meets earlier in the costumier’s shop, presage the elegant company who, soon afterwards, will pass sentence on Fridolin. Vehmic judges sat on rather sinister nocturnal councils which, in the Middle Ages, supplied rough justice in areas where the central authority was too weak to assert itself. The ironic allusion to the waning powers of the Hapsburg emperor is both subtle and unmistakable.

Schnitzler’s imaginary world neither outgrew nor spread beyond the empire which Franz-Josef kept together as much by his longevity as by the exercise of power. What Claudio Magris calls ‘the Hapsburg myth’ was an unceasingly fertile source of revisions and fantasies, sentimental or cruel, or both. Franz-Josef was, in many ways, more bourgeois than imperial: the supreme bureaucrat in a state where official respect for forms was para-mount. Like many Viennese males, the emperor went regularly to his office; like their emperor, many men had both wives and mistresses. Duplicity was a duty in a society where men were ashamed not to betray their partners and women were shameless if they did.

Schnitzler was a conformist rebel; he enjoyed the sweet wickednesses of which he was so accurate a chronicler. His affection for what he called ‘süsse Mädel’ (‘sweet young things’) was matched by the alacrity with which he replaced one with another. Anatol – a series of sketches about a smart man-about-Vienna much like himself – brought him fame by the time he was barely thirty and he never lost it. He wore success with elegant lack of surprise. He seemed to take himself no more seriously than his conquests. His reputation has perhaps suffered from his affectations of effortlessness.

The brevity and levity of Schnitzler’s style, not least in Dream Story, make it seem as if everything came easily to him. Because he was expert in the classic bourgeois genres — the boulevard play, the sophisticated magazine story — it is easy to miss the inventiveness and innovation he brought to them. He was one of the first novelists to use interior monologue; Fräulein Else is a neat instance (it too features a kind of delirious dream). Schnitzler’s method is to examine the ‘case history’ of his characters and to deal as briskly with them as if there were plenty of others in his waiting-room. In an essay on Fiction and the Medical Mode (1975), I pointed out that there was a link between writers as apparently diverse as — for obvious examples – Arthur Conan Doyle, Anton Chekhov and Somerset Maugham. All were doctors and all excelled in short fiction and in the terse use of dialogue; none had any use for fancy language.

Schnitzler’s abiding sense of the disintegration both of Austrian society and of its individual citizens has no clearer expression than Dream Story, in which a happy marriage is anatomized into the contrary impulses of murderous rage and reckless sensuality, of mutual desire and mutual revulsion, of tenderness and violence. Is a marriage to become stronger as a result of what seems to fracture it or is it fatally flawed? Schnitzler’s irony is so deftly attuned to the ambiguity of conjugal love that his pessimism, when read in a cheerful light, seems not to bar an optimistic reading. ‘Feelings and understanding,’ he once said, ‘may sleep under the same roof, but they run completely separate households in the human soul.’

The calm, almost chilly, tone of his narrative enables him to achieve what Wittgenstein tried to do in philosophy: say the new thing in the old language. Dream Story is erotic without being pornographic. It unsettles as much as it excites; like a dream, it recurrently threatens to come to a climax which eludes the protagonist as it does the reader. It is both explicit and decorous, outspoken and reticent, believable and incredible. Albertine’s dreams are what dreams might be, if they were more artistic and more explicit than usual.

Schnitzler does not scarify the surface of his text with literary experiment; he seems simply to track Fridolin in a world where dream and reality are no longer distinct. Do the events which so disconcert Fridolin ‘really’ take place? Or are the dreams which Albertine recounts in such cruel detail only part of an all-embracing dream which is the story as a whole? The narrative avoids unreality and absurdity by virtue of its unexcited, matter-of-fact vocabulary. With its realistic detail, Fridolin’s adventure seems to belong to the waking world, but does it? The reader must decide, though the use of ‘Denmark’ (as the password when Fridolin is seeking entry to the mysterious house where beautiful women are to be found) echoes, surely deliberately, the fact that Albertine’s dream lover is a Dane. Perhaps there was such an oneiric quality to life in Vienna that, as Schnitzler’s leading character says in Paracelsus,

. . . only those who look for a meaning will find it. Dreaming and waking, truth and lie mingle. Security exists nowhere. We know nothing of others, nothing of ourselves. We always play. Wise is the man who knows.

That knowing wisdom was at the centre of the solemn playfulness of Schnitzler’s art, and life.

SOURCE: Frederic Raphael. Introduction to Dream Story, by Arthur Schnitzler, translated by J. M. Q. Davies, pp. V-XVII. New York: Penguin, 1999.