The Conspiracy Against the Human Race: A Contrivance of Horror

by Thomas Ligotti, Ray Brassier (Foreword)

This great writer of horror presents a philosophy to curl your hair. It should force you to re-examine the roots of everything that you believe and offer you a freedom you are not likely to find anywhere else.

by Szplug

Ligotti is a pessimist—and not some namby-pamby, equivocating, of course it will rain every day of my vacation! kind of doubting dude: Ligotti’s pessimism is old school, pure, richly endowed with the ichor of nullity. Ligotti believes, firmly and avowedly, that, as the human race would have been better off never having come into existence in the first place, the most beneficial and sensible outcome for our species, as constituted at this particular point in the space/time continuum, would be to voluntarily abstain, to a single man and woman, from producing anymore offspring; and thus extinguish our brutal ontological dilemma with a self-enforced and -executed extinction. What, exactly, comprises this dilemma, to such a degree that a willingly undertaken mass-snuffout seems a sensible solution? It is consciousness, that horrible awareness bestowed upon our otherwise animal and natural fleshly bodies that divides us from ourselves, irreparably separates us from the physical world from which we were sprung. Whether this horrible gift was endowed by a supernatural agency or evolutionary development, it long ago metastasized, inflating itself to absurd proportions that cannot be reconciled to the bestial beings in which it is forced to reside. The result is endless torment and suffering, as this consciousness can contemplate both itself and the world, and can anticipate such inevitable mental excruciations as pain, terror, loss, forgetfulness and—the end point ineluctably awaiting on the horizon—death. Alone in nature do we have the capacity to reflect upon the past and contemplate the future—and, thus, we are aware of the futility and ephemerality of our hopes and desires, in both what has and what will crumble to dust.

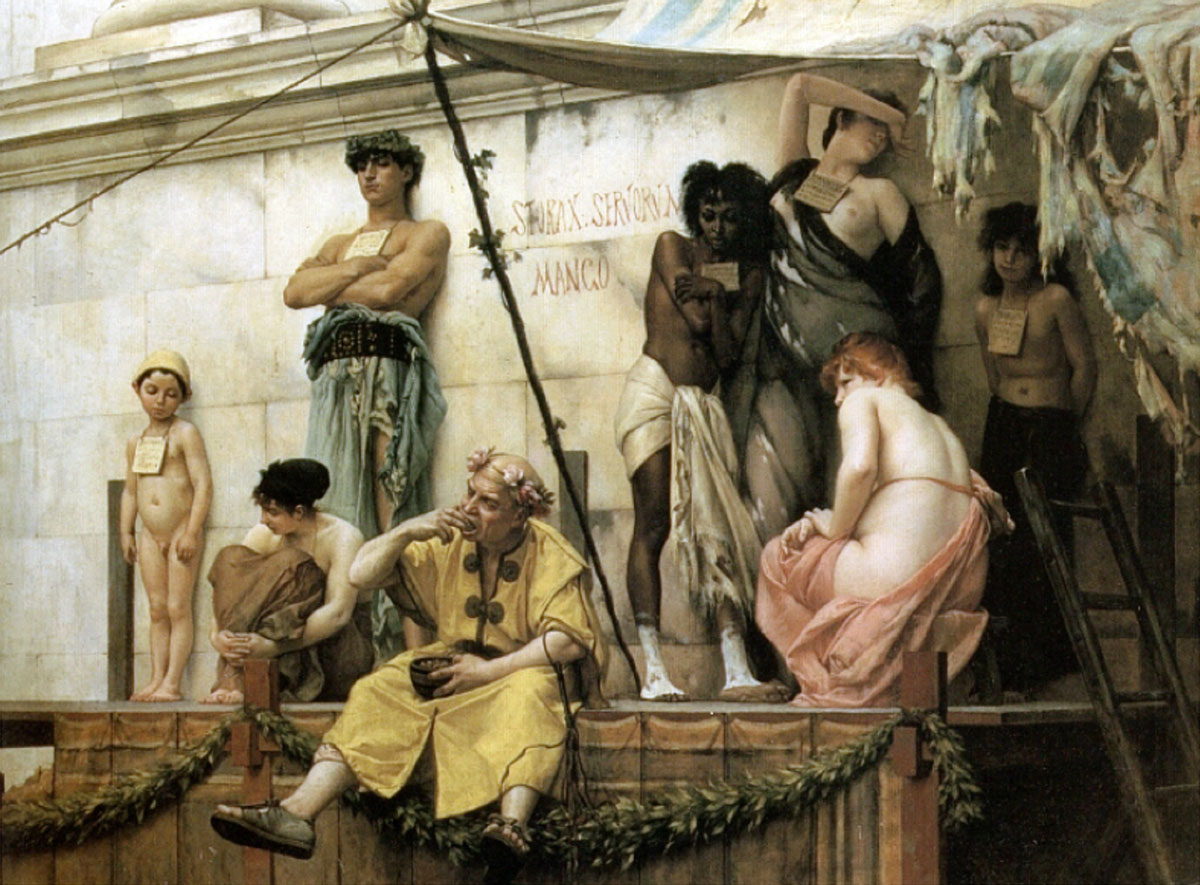

Though we may experience pleasures and fulfillments, can pass along a portion of our inner-selves through our genetically-generated offspring, our individualities cannot be reconciled to the temporality of our allotted time and the fact that death awaits us, if not in the next second, then at some point in the days ahead; and this, along with a thousand other cuts, are what perpetuate the torment that comprises the centre of our conscious existence. We have established individual, societal, and mental edifices and constructions—illusionary all—in an effort to conceal these bald truths and allow us to proceed with the business of getting on getting on; but it is all a thinly-veiled chimera. We isolate this unpleasant reality where it can be ignored; we anchor ourselves within structures such as religion, families, and ideologies; we distract ourselves through our work, our hobbies, our immersion in mediums such as television and the internet; and we sublimate the truth we have dealt with by these previous methods within that which we create ourselves. It would take but the slightest of perspective alterations for the true and unadulterated horror of our reality to burst forth in all its macabre might: we are puppets, drawn away from the verity of our contingent nature by the charade of freedom that we have so powerfully enacted; fleshly vessels possessed of nothing at all like the self that we so stubbornly continue to believe comprises our wonderfully unique and individualized persons; and then madness—perhaps the truest state in which we can be rendered—would perforce overwhelm all of our controls. We are insane, string-operated, death-bound creatures threaded daily through the needle of suffering—and there is no respite in store for us in any direction, from any quarter. Thus, we would be better off with non-existence: painless, non-conscious, nothingness.

So sayeth the pessimist. Ligotti freely admits that, throughout history, this has been a position held by a tiny minority of the population, surrounded by a wealth of optimists who believe that it is better to be alive than to be dead, that every day, in some way, we are getting better, and that hope springs eternal. These optimists have constructed religions, philosophies, political theories, and cultures to reflect this belief that life is worth living; what’s more, they cannot abide that which the pessimist says, sensing the discomfiting viability of their bleak outlooks—and so such dark individuals are exiled from the commonality of popular and accepted thought. To pessimists such as Ligotti, however, these magnificently grim and sober naysayers produced the only type of food for thought that provides the necessary nourishment; and the author takes us upon tours of the output of these profound pessimists who have filled him with the emptiness of their ontological negation. These are names we have all heard of—Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Cioran, Lovecraft—and those dredged from the deepest obscurity—Zapffe, Mainländer, Saltus. Some have qualified their pessimism, such that human extinction forms no part of their solution; the majority advocate our termination, seeing it as the reasonable response to our paradoxical existence. The state of our bifurcation has been attributed to a suicidal deity self-rent into a billion awarenesses in order to dilute and destroy itself; to a nature that ripened consciousness to an absurd degree, in order to endgender beings who would perforce, through alienation, destroy their creational environment; and to a simple evolutionary progression that exceeded itself by the grossest of over-exuberant mutations; in any event, all of these outlooks point towards a singular reality: that we inhabit a universe which, together with every single thing contained therein, can only be regarded as MALIGNANTLY USELESS.

Of course, Ligotti declares from the very start that such pessimism is unprovable—you either believe it to be so, or—as a majority does—you don’t. It is unlikely that such arguments will persuade those not innately inclined to such bleak conclusions. What’s more, so pervasively has the desirability of living been engendered within us by our consciousness, and the illusionary frameworks it has empowered us to fabricate, that even the most unshakeable of pessimists will often live out their lives until some manner of death extinguishes their flame. Whilst the undesirability of a continued existence for humanity may have made itself perfectly clear in one’s mind, it is quite another thing to wield this belief in the manner that logic dictates it be so used; this consciousness is powerful stuff indeed.

This was a great read—Ligotti is a perfect writer for such a topic: his prose style, so sober and deadpan and inexorable, is yet propelled by an undercurrent of the darkest and driest of humor. Laughing out loud while reading a work of such implacable and relentless negativity is an amazing state of affairs; the highest of compliments should be paid to an author who can so skillfully render such a result from razor-blade ruminations. What’s more, his analysis of the uncanny and our fleeting awareness of its presence in the quotidian, and the way in which it has been explored in literature and film, philosophy and thought, was very good, as was his exploration of the supernatural and how it functions as a form of the sublimation that he—and thinkers like Zapffe—hold to be one of the principal measures of our ability to hold off the starkly overwhelming reality of our existential predicament, doing so in works ranging from Shakespeare to Lovecraft, from Radcliffe to James. Other than the occasional tendency to melodramatic and overblown phrasing, a nod to his origins as a penner of horror fiction, Ligotti delivers such material with keen insights and an assured touch. I enjoyed his takes, and his reproduction of the takes of others, on such subjects very much.

I am what Ligotti would refer to as an optimistic pessimist: I have no hope; I awake each day with a heightened horror, shaken by the quenching afterimages of that wasteland which I espy so clearly with sleep-lidded eyes; I am riven again and anew by the contemplation of all the impossible angles that abound in this scratchy, acrylic absurdity called my existence, the anile and awkward measures I enact in order to endure through to another sunset; and yet, within this internal darkness, I have access to an ineradicable source of light and laughter and belief in this crazy, irrational species with which I share my ridiculous existence on this planet. I have little hope for mankind, abundant hope for man. I dread the interminability of my remaining days upon this earth, with the bleakscape shuttered away I thrill with each dawn at the possibilities inherent within that particular day. Whereas Ligotti looks at our reality and sees no reason to exist, I look from a similar vantage point and cannot see any reason not to. Certainly we operate behind a palimpsest of barriers and shields that we have concocted in order to draw our attention away from a naked and morbid obsession with our unique status within this existence—the conspiracy overseen by our perverted consciousness—but so what?

Such a determined and enduring struggle against a universe ever revealing itself in its infinite wonder, and reducing our status within it to that of motes of wholly insignificant dust, strikes me as impressive and worthy of admiration, not a mad folly to be discontinued with malice as we take stock of exactly how utterly alone and determined we are. It is the refusal to bow to what seems inevitable that has always comprised the most valuable part of what constitutes that which we label the spirit of humanity. It is our knowledge of suffering that has allowed us to produce works of art, in such a wide variety of mediums, that have so profoundly and deeply and inspiringly touched and moved one another; allowed us to cross the seemingly infinite and eternal spaces that separate us and given us enough of the touches of the other to fortify us for another day. It is that flip-side of hatred, the passionate attachment to another doomed being that we call love, which exposes us to so much that enriches and enhances our brief passage through a world irreconcilable with a mind that cannot endure this core conflict between materiality and awareness. I am inherently inclined to accept a considerable proportion of Ligotti’s diagnosis—and I am also inherently inclined to reject the majority of his proposed cure. With that said, this is a book whose contents I appreciate taking inside, with all of the enlightening, engaging, discomfiting, and enjoyable directness that comprised it; and I must say, that to reap such positive benefits from a work of unequivocal negation makes for a surprising but pleasant experience.

First published on Goodreads, August 06, 2011