I am in the habit of thinking of myself as a Rationalist; and a Rationalist, I suppose, must be one who wishes men to be rational. But in these days rationality has received many hard knocks, so that it is difficult to know what one means by it, or whether, if that were known, it is something which human beings can achieve. The question of the definition of rationality has two sides, theoretical and practical: what is a rational opinion? and what is rational conduct? Pragmatism emphasises the irrationality of opinion, and psycho-analysis emphasises the irrationality of conduct. Both have led many people to the view that there is no such thing as an ideal of rationality to which opinion and conduct might with advantage conform. It would seem to follow that, if you and I hold different opinions, it is useless to appeal to argument, or to seek the arbitrament of an impartial outsider; there is nothing for us to do but to fight it out, by the methods of rhetoric, advertisement or warfare, according to the degree of our financial and military strength. I believe such an outlook to be very dangerous, and, in the long run, fatal to civilisation. I shall, therefore, endeavour to show that the ideal of rationality remains unaffected by the ideas that have been thought fatal to it, and that it retains all the importance it was formerly believed to have as a guide to thought and life.

To begin with rationality in opinion: I should define it merely as the habit of taking account of all relevant evidence in arriving at a belief. Where certainty is unattainable, a rational man will give most weight to the most probable opinion, while retaining others, which have an appreciable probability, in his mind as hypotheses which subsequent evidence may show to be preferable. This, of course, assumes that it is possible in many cases to ascertain facts and probabilities by an objective method—i.e., a method which will lead any two careful people to the same result. This is often questioned. It is said by many that the only function of intellect is to facilitate the satisfaction of the individual’s desires and needs. The Plebs Text-Books Committee, in their Outline of Psychology (p. 68), say: ‘The intellect is above all things an instrument of partiality. Its function is to secure that those actions which are beneficial to the individual or the species shall be performed, and that those actions which are less beneficial shall be inhibited’ (italics in the original).

But the same authors, in the same book (p. 123), state, again in italics: ‘The faith of the Marxian differs profoundly from religious faith; the latter is based only on desire and tradition; the former is grounded on the scientific analysis of objective reality.’ This seems inconsistent with what they say about the intellect, unless, indeed, they mean to suggest that it is not intellect which has led them to adopt the Marxian faith. In any case, since they admit that ‘scientific analysis of objective reality’ is possible, they must admit that it is possible to have opinions which are rational in an objective sense.

More erudite authors who advocate an irrationalist point of view, such as the pragmatist philosophers, are not to be caught out so easily. They maintain that there is no such thing as objective fact to which our opinions must conform if they are to be true. For them opinions are merely weapons in the struggle for existence, and those which help a man to survive are to be called ‘true’. This view was prevalent in Japan in the sixth century AD, when Buddhism first reached that country. The Government, being in doubt as to the truth of the new religion, ordered one of the courtiers to adopt it experimentally; if he prospered more than the others, the religion was to be adopted universally. This is the method (with modifications to suit modern times) which the pragmatists advocate in regard to all religious controversies; and yet I have not heard of any who have announced their conversion to the Jewish faith, although it seems to lead to prosperity more rapidly than any other.

In spite of the pragmatist’s definition of ‘truth’, however, he has always, in ordinary life, a quite different standard for the less refined questions which arise in practical affairs. A pragmatist on a jury in a murder case will weigh the evidence exactly as any other man will, whereas if he adopted his professed criterion he ought to consider whom among the population it would be most profitable to hang. That man would be, by definition, guilty of the murder, since belief in his guilt would be more useful, and therefore more ‘true’, than belief in the guilt of anyone else. I am afraid such practical pragmatism does sometimes occur; I have heard of ‘frame-ups’ in America and Russia which answered this description. But in such cases all possible efforts after concealment are made, and if they fail there is a scandal. This effort after concealment shows that even policemen believe in objective truth in the case of a criminal trial. It is this kind of objective truth—a very mundane and pedestrian affair—that is sought in science. It is this kind also that is sought in religion so long as people hope to find it. It is only when people have given up the hope of proving that religion is true in a straightforward sense that they set to work to prove that it is ‘true’ in some newfangled sense. It may be laid down broadly that irrationalism, i.e., disbelief in objective fact, arises almost always from the desire to assert something for which there is no evidence, or to deny something for which there is very good evidence. But the belief in objective fact always persists as regards particular practical questions, such as investments or engaging servants. And if fact can be made the test of the truth of our beliefs anywhere, it should be the test everywhere, leading to agnosticism wherever it cannot be applied.

The above considerations are, of course, very inadequate to their theme. The question of the objectivity of fact has been rendered difficult by the obfuscations of philosophers, with which I have attempted to deal elsewhere in a more thoroughgoing fashion. For the present I shall assume that there are facts, that some facts can be known, and that in regard to certain others a degree of probability can be ascertained in relation to facts which can be known. Our beliefs are, however, often contrary to fact; even when we only hold that something is probable on the evidence, it may be that we ought to hold it to be improbable on the same evidence. The theoretical part of rationality, then, will consist in basing our beliefs as regards matters of fact upon evidence rather than upon wishes, prejudices, or traditions. According to the subject-matter, a rational man will be the same as one who is judicial or one who is scientific.

There are some who think that psycho-analysis has shown the impossibility of being rational in our beliefs, by pointing out the strange and almost lunatic origin of many people’s cherished convictions. I have a very high respect for psycho-analysis, and I believe that it can be enormously useful. But the popular mind has somewhat lost sight of the purpose which has mainly inspired Freud and his followers. Their method is primarily one of therapeutics, a way of curing hysteria and various kinds of insanity. During the war psycho-analysis proved to be far the most potent treatment for war-neuroses. Rivers’s Instinct and the Unconscious, which is largely based upon experience of ‘shellshock’ patients, gives a beautiful analysis of the morbid effects, of fear when it cannot be straightforwardly indulged. These effects, of course, are largely non-intellectual; they include various kinds of paralysis, and all sorts of apparently physical ailments. With these, for the moment, we are not concerned; it is intellecual deragements that form our theme. It is found that many of the delusions of lunatics result from instinctive obstructions, and can be cured by purely mental means—i.e., by making the patient bring to mind facts of which he had repressed the memory. This kind of treatment, and the outlook which inspires it, pre-suppose an ideal of sanity, from which the patient has departed, and to which he is to be brought back by making him conscious of all the relevant facts, including those which he most wishes to forget. This is the exact opposite of that lazy acquiescence in irrationality which is sometimes urged by those who only know that psycho-analysis has shown the prevalence of irrational beliefs, and who forget or ignore that its purpose is to diminish this prevalence by a definite method of medical treatment. A closely similar method can cure the irrationalities of those who are not recognised lunatics, provided they will submit to treatment by a practitioner free from their delusions. Presidents, Cabinet Ministers and Eminent Persons, however, seldom fulfil this condition, and therefore remain uncured.

So far, we have been considering only the theoretical side of rationality. The practical side, to which we must now turn our attention, is more difficult. Differences of opinion on practical questions spring from two sources: first, differences between the desires of the disputants; secondly, differences in their estimates of the means for realising their desires. Differences of the second kind are really theoretical, and only derivatively practical. For example, some authorities hold that our first line of defence should consist of battleships, others that it should consist of aeroplanes. Here there is no difference as regards the end proposed, namely, national defence, but only as to the means. The argument can therefore be conducted in a purely scientific manner, since the disagreement which causes the dispute is only as to facts, present or future, certain or probable. To all such cases the kind of rationality which I called theoretical applies, in spite of the fact that a practical issue is involved.

There is, however, in many cases which appear to come under this head a complication which is very important in practice. A man who desires to act in a certain way will persuade himself that by so acting he will achieve some end which he considers good, even when, if he had no such desire, he would see no reason for such a belief. And he will judge quite differently as to matters of fact and as to probabilities from the way in which a man with contrary desires will judge. Gamblers, as everyone knows, are full of irrational beliefs as to systems which must lead them to win in the long run. People who take an interest in politics persuade themselves that the leaders of their party would never be guilty of the knavish tricks practised by opposing politicians. Men who like administration think that it is good for the populace to be treated like a herd of sheep, men who like tobacco say that it soothes the nerves, and men who like alcohol say that it stimulates wit. The bias produced by such causes falsifies men’s judgements as to facts in a way which is very hard to avoid. Even a learned scientific article about the effects of alcohol on the nervous system will generally betray by internal evidence whether the author is or is not a teetotaller; in either case he has a tendency to see the facts in the way that would justify his own practice. In politics and religion such considerations become very important. Most men think that in framing their political opinions they are actuated by desire for the public good; but nine times out of ten a man’s politics can be predicted from the way in which he makes his living. This had led some people to maintain, and many more to believe practically, that in such matters it is impossible to be objective, and that no method is possible except a tug-of-war between classes with opposite bias.

It is just in such matters, however, that psycho-analysis is particularly useful, since it enables man to become aware of a bias which has hitherto been unconscious. It gives a technique for seeing ourselves as others see us, and a reason for supposing that this view of ourselves is less unjust than we are inclined to think. Combined with a training in the scientific outlook, this method could, if it were widely taught, enable people to be infinitely more rational than they are at present as regards all their beliefs about matters of fact, and about the probable effect of any proposed action. And if men did not disagree about such matters, the disagreements which might survive would almost certainly be found capable of amicable adjustment.

There remains, however, a residuum which cannot be treated by purely intellectual methods. The desires of one man do not by any means harmonise completely with those of another. Two competitors on the Stock Exchange might be in complete agreement as to what would be the effect of this or that action, but this would not produce practical harmony, since each wishes to grow rich at the expense of the other. Yet even here rationality is capable of preventing most of the harm that might otherwise occur. We call a man irrational when he acts in a passion, when he cuts off his nose to spite his face. He is irrational because he forgets that, by indulging the desire which he happens to feel most strongly at the moment, he will thwart other desires which in the long run are more important to him. If men were rational, they would take a more correct view of their own interest than they do at present; and if all men acted from enlightened selfinterest the world would be a paradise in comparison with what it is. I do not maintain that there is nothing better than selfinterest as a motive to action; but I do maintain that self-interest, like altruism, is better when it is enlightened than when it is unenlightened. In an ordered community it is very rarely to a man’s interest to do anything which is very harmful to others. The less rational a man is, the oftener he will fail to perceive how what injures others also injures him, because hatred or envy will blind him. Therefore, although I do not pretend that enlightened self-interest is the highest morality, I do maintain that, if it became common, it would make the world an immeasurably better place than it is.

Rationality in practice may be defined as the habit of remembering all our relevant desires, and not only the one which happens at the moment to be strongest. Like rationality in opinion, it is a matter of degree. Complete rationality is no doubt an unattainable ideal, but so long as we continue to classify some men as lunatics it is clear that we think some men more rational than others. I believe that all solid progress in the world consists of an increase in rationality, both practical and theoretical. To preach an altruistic morality appears to me somewhat useless, because it will appeal only to those who already have altruistic desires. But to preach rationality is somewhat different, since rationality helps us to realise our own desires on the whole, whatever they may be. A man is rational in proportion as his intelligence informs and controls his desires. I believe that the control of our acts by our intelligence is ultimately what is of most importance, and what alone will make social life remain possible as science increases the means at our disposal for injuring each other. Education, the press, politics, religion—in a word, all the great forces in the world—are at present on the side of irrationality; they are in the hands of men who flatter King Demos in order to lead him astray. The remedy does not lie in anything heroically cataclysmic, but in the efforts of individuals towards a more sane and balanced view of our relations to our neighbours and to the world. It is to intelligence, increasingly wide-spread, that we must look for the solution of the ills from which our world is suffering.

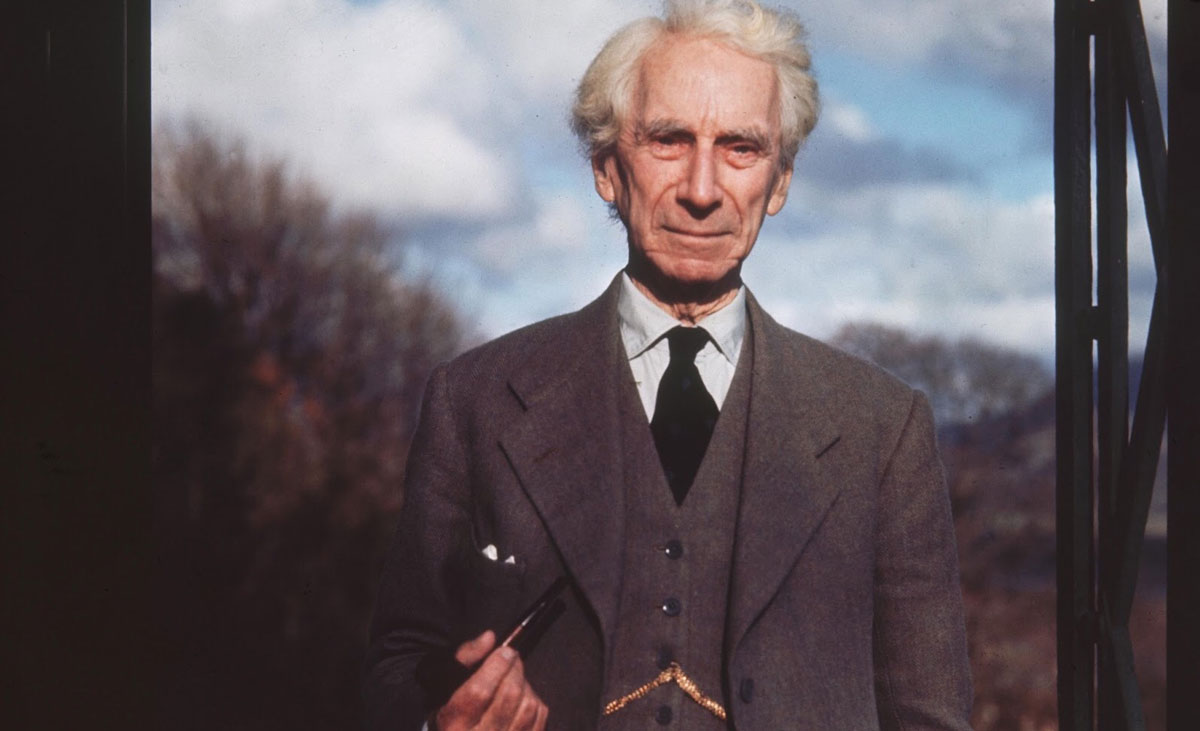

Bertrand Russell, Sceptical Essays, 1928