Yorgos Lanthimos is a filmmaker with an insatiable appetite. His gaze is ravenous, almost bulimic. He’s not satisfied with mere observation, framing, and presenting; he seeks to engulf as much of the world as possible in his vision. He wants to devour the visible. And so, he expands it with prisms, optical distortions, fish-eye lenses, and a bold use of wide angles.

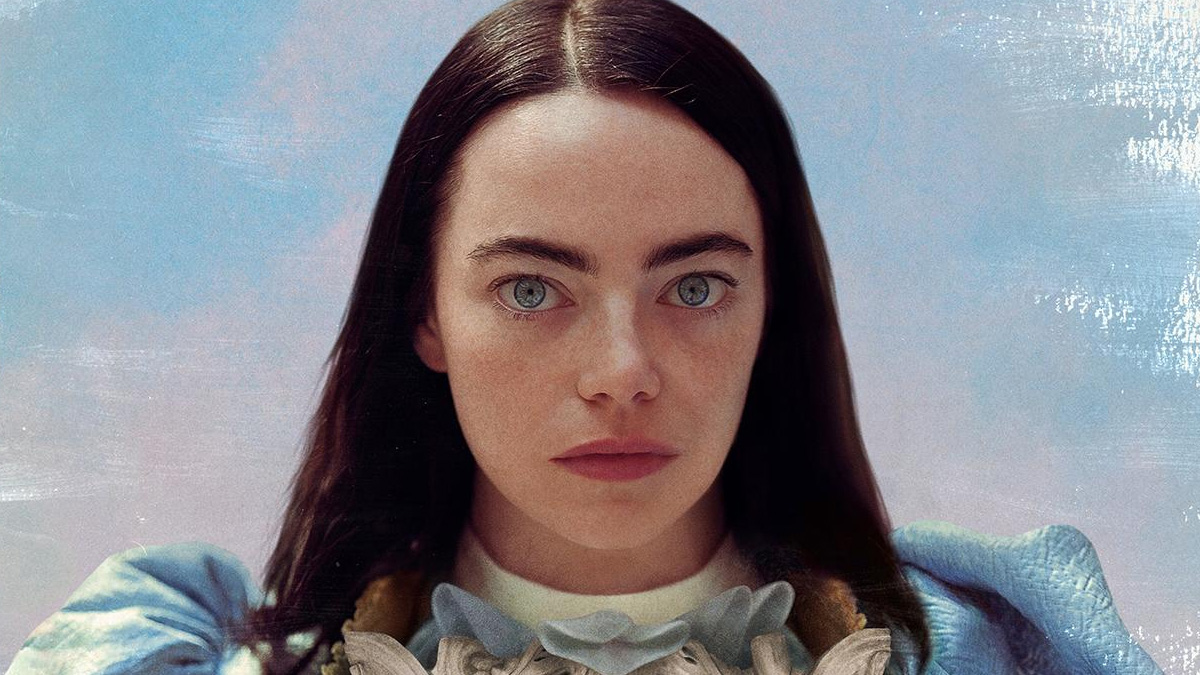

In Poor Things – his film that clinched the Golden Lion at the last Venice Film Festival – there’s not a single realistic shot. Everything is distorted, bent, enlarged, stretched. As if the direction tunes its gaze to the same wavelength as its protagonist: the enchanting Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), a mutating maiden hungry for life, movement, and sexuality. She devours the world, men, penises, books, foods. He – Yorgos – devours her.

She is a creature monstrous in her own way: a Victorian mad doctor (Willem Dafoe), his face marred by scars, finds her suicidal with a baby in her womb. Cynical and Promethean, the surgeon removes the infant’s brain and transplants it into the woman’s skull, making her simultaneously mother and “daughter of her own son”. But Dante’s Virgin of Paradise is nowhere in sight: here we are more in the realm of the gothic. Dark, nocturnal, visionary. Bella stumbles through the world. She has the body of a woman and the brain of an infant. She has desires and needs that her brain cannot comprehend or control. Yet, she wants to learn. She wants to know. Gradually, she masters words, language, movement. Then she discovers the body and the pleasure it can give – through sex. Craving knowledge and experiences, Bella leaves her creator (aptly named Godwin, reminiscent of God even in name) and ventures into the world’s discovery.

The film that tells her story is constructed in her image. It’s a Frankenstein film, skillfully stitched together from fragments taken from other cinematic bodies/corpses, from horror to gothic, from libertine apologue to bildungsroman.

Lanthimos frequents the morgues of the imagination, recovers corpses, and brings them back to life, just like God in his film. As for Bella, after discovering the pleasure of sex, she pursues what she calls “furious spasms” with sweet lightness and grace, wreaking havoc in the minds of men she encounters and causing devastating effects on the lives of all those close to her.

With sumptuous set designs, refined pictorial references (from Pre-Raphaelite bodies to Salvador Dalì-like animal hybrids), and photography of exceptional chromatic and luminous power, Lanthimos signs a work that leaves one agape for the richness of its staging, the beauty of some images, and the fiery use of computer graphics: a film that delves deeply into the nature of desire, deflating and sidelining prejudices and taboos.

In a cameo, set on a ship, even a great actress like Hanna Schygulla, muse of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, appears. Here she is an elderly lady, chaste for over twenty years, immersed in colors and lights reminiscent of Fassbinder’s Querelle de Brest: fittingly, an apple tree, an impossible love story, as the possible matrix of a film investigating the mysteries, contradictions, and taboos of love.

In the end, it’s almost inevitable to wonder who the “poor things” evoked in the title are. Given the outcome of the story, and its protagonists, it almost naturally occurs that perhaps, ultimately, the poor things to be pitied are us, the viewers, incapable of growing, changing, daring, and risking as the characters in the film show they can.

[Translation by Chris Montanelli]