by Ken Kelley

Though I had prepped myself carefully, I was altogether unready for what I found when I finally met the real Woody Allen, after weeks of delicate negotiations which finally culminated in his agreeing to be interviewed. First there was the matter of his size—he stood 6‘6″, weighed 245. Kind of broad at the shoulders and narrow at the hips. I was ushered into his presence by a bevy of midgets, who constantly surround him and on whom he depends for everything. Before I could see him, I had to put on a pair of weird emerald green glasses.

Then there was the matter of his voice—a pronounced South Topeka twang. And, most disturbing, his penchant for pulling practical jokes. Through his big com-fed teeth he grinned a “Howdy, podna,” and his huge hammy hunk of hand gripped mine, viselike, whereupon an electric buzzer on his index finger sent me into jangled paroxysms. “Har, har, har,” he said, just as the red boutonniere on his lapel sprayed my startled physiognomy with lemonade. Then one of the ubiquitous midgets set my socks on fire, while another crept up behind me and knelt. With split- second timing Woody Allen pushed me over the midget, landing me in a ruffled heap on the floor. He then proffered the aforementioned hand to help me up and, sucker that I was, the buzzer jolted me once again. “Shucks, this is just our way of sayin’ welcome, boy,” he drawled, slapping me so heartily on the back that my phlegm sank to my ankles.

At this point I was sufficiently discombobulated and miffed to chuck the whole thing—I wasn’t getting paid enough to put up with the antics of this big bumpkin. Then I noticed that one of the midgets—one who stood head and shoulders above the others, actually—had an appreciably different air about him from the rest of the pack. A slight, boyish-looking human, perhaps 5’6″, with thick, black-rimmed glasses, eyes that were limpid pools of paranoia, a selfdeprecating half frown on his face. He was sitting off in a corner, starting idly into space, rather obviously contemplating the answers to life, then carefully jotting down the questions in a loose-leaf binder.

After conversing with him for several minutes while the madcap frivolity swirled around us, I decided I really liked him. He was the kind of really decent, kind, thoughtful, thrifty, brave, clean and reverent guy you’d be proud to have your sister marry. He saw a copy of Woody Allen’s latest book under my arm, Without Feathers, a compilation of Allen’s humorous essays culled from the New Yorker and other magazines, which was ten weeks on the best-seller list, and said with a poignant sincerity, “I hope you didn’t have to pay for that.

When I told him I had lifted it from Brentano’s he smiled wistfully. This man’s name, it turned out, was Allan Stewart Konigsberg. He was forty years old, he said, and with a subdued modesty he told me he was the “eminence grise” (which translated loosely from the French as “grizzled antler”) behind Woody Allen.

I had an important decision to make. After fully five minutes, I had made it.

Though still wracked with doubt, I decided that I would interview this chap instead of the real Woody Allen, whose churlish ways were so boring. After six hours I knew I had made the right choice, though when Konigsberg claimed to be the reincarnation of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Freud, I turned the tape recorder off. During the entire session he smiled three times—an event tantamount to the arrival of Halley’s comet, I later learned—and cracked not a single joke.

What a relief. “Sic semper” cerebrum.

KELLEY: This may sound like a funny question, but do you consider yourself a comedian?

ALLEN: Yes, definitely. I had great trepidation about calling myself that years ago when I first switched from writing to comedy. But now unequivocally I call myself a comedian.

KELLEY: As a comedian, then, the opportunity to make movies is a rare one—to have complete control. Have you broken any new ground?

ALLEN: I’ve never had any ulterior motive in terms of style or content or breaking new ground or anything like that. The only interest to me was making people laugh.

KELLEY: Which movie have you had the most fun making?

ALLEN: None of them have been any fun at all. They’ve all been terrific anxiety and hard work. And for my own goals, I would consider all the movies that I’ve done failures. It’s very hard to get a conception and transfer it in that idealized form right to the end. It takes an enormous amount of concentration and luck. And it’s always been beyond my capability up to this point. I always finish and say, “Ugh—I only got 60 percent of that idea that worked and what a shame.”

Then you put it out and you hope the critics will like the picture. You hope they like it because you’re involved in an economically burdened art—for me. I write for the New Yorker magazine strictly as a hobby now—I don’t need the money. And when my books come out I couldn’t care less about it—it’s strictly for my own enjoyment. But a film may well cost $2 or $3 million, so I do care that they are well received. But I don’t think what the critics say about them necessarily bears any actual relation to any objective reality about them in any sense whatsoever. I think it’s totally subjective. And somewhere in the equation, that fact gets lost, because they appear in print, and that has objective charisma.

KELLEY: Did you see Russell Baker’s criticism of Love and Death—that Woody Allen once again plays the poor schmuck, but the guy who nevertheless gets the girl at the end? . . .

ALLEN: Right. There’s just no way to please people. Now some people say to me, “You should never get the girl,” where others say, “You should get the girl, we root for you to get the girl.” If I was actually to look at all the things written about me from very respectable people who have not been hostile but who have tried to be constructive—it’s all so utterly disparate that I just wouldn’t know what to do.

KELLEY: So you only try to please yourself . . .

ALLEN: First myself. I want to please an audience—to make an audience laugh—that’s the idea. If I write a joke and after a couple of times nobody laughs, I take it out of the movie—I don’t want to indulge myself that much. If I have the slightest doubt, I leave it out. I’ve left out many, many very good jokes. But I never put anything in a movie that the audience would like that I don’t like—I would never do that. Sometimes there will be a bad thing in my films because I’ve either guessed wrong or judged wrong. Or for some reason or other, every conceivable alternative was bad and this is the best one I have.

You really have to make an effort not to judge critics, because one s natural bodily impulses are to react positively to praise and negatively to criticism. But in the true scheme of things it means nothing, nothing at all, except possibly in economic terms. I’ve been lucky because for the most part I’ve done very well—economically that is, not in my own personal terms. But if I open a film and the basic critics that send people to movies—the New York Times, Time—all didn’t like my movie, I would feel the reverberations economically and that makes it tougher to put the next movie out. That’s what bothers you.

Comedy is like playing the drums. Every guy in the world comes up to the bandstand during the breaks on Monday nights when I’m playing clarinet with a band at Michael’s Pub in New York, and each guy thinks he can play the drums better. And, everybody thinks he’s the expert on comedy. It’s totally subjective.

KELLEY: “But subjectivity is objective.”

ALLEN: That’s what throws you all the time.

KELLEY: If you don’t enjoy making movies, why do you make them?

ALLEN: I know this sounds facetious but I do movies because I have the opportunity, and I’m living in a world where everybody wants to do movies. And I’m in, through no fault of my own, through a series of bizarre quirks, a position where I write, direct and star in my own films.

I have total control over them, final cut. No one approves the script. I have everything going for me. And it all happened so accidentally—had you told me fifteen years ago that I was going to be the lead in a movie I would have thought you were crazy. It’s the funniest thing in the world to me. So I make movies because I feel if I don’t make them, someday I’ll look back and think to myself, “They were dumping this stuff in my lap and I didn’t take advantage of it.” So I do it.

KELLEY: How did Love and Death do commercially?

ALLEN: It was probably the greatest commercial success I’ve had, which is not saying very much because I’m not an enormously commercial filmmaker. I have to get terrific reviews to be a decent hit, which happened with Love and Death and Sleeper. I rarely see any money on my percentage arrangement with United Artists—my films just don’t make enough. I’d need a Graduate or something to really get it. I could make a lot more money if I worked as a comedian in clubs—I get very little, either to make them or for salary. I make less to write a script, direct a movie and star in it than what a star gets just for starring—about two-thirds less. So I’m not out to take the money and run, I’m in it for the chance to make pictures. But I’m sure that Young Frankenstein made an enormous amount more than Bananas, Sleeper and Love and Death all put together. And that Blazing Saddles made more than all my movies put together.

KELLEY: Did you enjoy those movies?

ALLEN: I saw Frankenstein on a plane. It was very amusing. I’m a very good audience for comedy and a good audience for Mel Brooks. He’s an old acquaintance of mine. I enjoy him, I’m an easy laugher at his things.

KELLEY: I guess his 2000-Year-Old Man is the comedic masterpiece.

ALLEN: I had written with Mel at the Sid Caesar show. I had been writing for Sid and someone said that Mel was going to be writing for Sid now and “he’s just going to eat you alive, he’s so difficult to get along with and he’s so high-pressured.” And I girded myself for a really unpleasant experience. And then he came on the show—he had written for Sid before—and he was just as nice, amusing, intelligent as could be—he was so nice to me. So I’ve had very good experiences with him. And, of course, he’s obviously funny—that combined with my liking him so much, I laugh at his movies.

KELLEY: Was Sid Caesar your favorite comedian?

ALLEN: Sid was my favorite—no fun to work with at all but a brilliant comedian. Jackie Gleason I liked, and the Marx Brothers—my favorite overall was Groucho.

KELLEY: Do you watch a lot of other people’s movies?

ALLEN: In spurts. I go for a while and then I don’t see any for a while.

KELLEY: What other director do you really admire?

ALLEN: Really the only ones I have any interest in at all are Bergman, Antonioni, Renoir, Bunuel—basically serious stuff. I don’t have an enormous interest in comedies.

KELLEY: Do you learn a lot technically by watching their stuff—camera shots, lighting, that kind of thing?

ALLEN: No more. A move from zero to one is the best learning experience. Then your rate of progress slows down enormously. So mine is really slowed down. I learned a lot going from a nonfilmmaker to a filmmaker with the first film or two. I’ve gotten more proficient at not making as many mistakes.

KELLEY: You jumped from a futuristic treatment in Sleeper back to nineteenth- century Russia in Love and Death. What’s next—Jane Austen?

ALLEN: I’m almost through shooting it, but I don’t want to talk too much about it, because I always keep these things secret. It’s a much more realistic, contemporary story. It’s a comedy and for laughs. But it takes place in New York, now. It’s not a costume or surrealistic kind of story—it’s more romantic and more understandable.

KELLEY: You worked for Caesar in the early fifties?

ALLEN: Right.

KELLEY: Do you have a strong recollection of the fifties?

ALLEN: I have a very strong recollection of the forties—those were my formative years. I remember the fifties without any great feeling. . . .

KELLEY: Yet you’re in a movie right now that deals with a very important aspect of the fifties—blacklisting in Hollywood. In fact, The Front is the first picture you’ve been in since you started directing where you didn’t write the script and didn’t direct Why did you decide to do it?

ALLEN: You know, the blacklisting was really after World War II, all the anticommunist propaganda was at a high point then. I remember hearing about blacklisting when I was in public school—not really understanding the implications of it at all. But in retrospect, what I know now historically, it was a horrible time. The script expresses me politically even though I didn’t write it. It was one of the best pieces of material offered to me. People that offer me material to do generally offer me comedies and I’m not interested in them because I write my own—I don’t need them.

Also, what they offer me is terrible. Usually they are much further out than anything I would write—people have a conception of me like they have of Salvador Dali—that I’m so far out, which I’m not. And the other kinds of comedies I get from people are dirty, really filthy scripts and they are always stupid. It’s very rare that anybody offers me anything decent at all. This was a very substantial political script, so it was fun to try and act in something seriously and, of course, something with a political position that expresses me. I would not do a film that didn’t express me politically.

KELLEY: You mean it presents your point of view generally?

ALLEN: Yeah. You know, this is no revolutionary position to take. I hated McCarthy, I hated blacklisting, the whole concept of it. So to that extent it expresses me politically. Also, the script is very interesting because both the director, Marty Ritt, and the writer, Walter Bernstein, were blacklisted then—it has a real ring of truth to it. If this picture comes off I think it will be a picture about a very substantial political subject.

KELLEY: It’s hard to believe that such a handful of idiots could have exerted enough pressure to destroy people’s lives and strangle a whole industry— indeed, a whole country. How did we move to the point where Jane Fonda can go to North Vietnam in the midst of the war and still get an Oscar, or that Jack Nicholson can talk about taking LSD in Time, whereas when Robert Mitchum was busted for pot in 1948 he declared publicly that his career was over?

ALLEN: Well, liberals, in my opinion, are always more correct. And the trend of progress is always the liberalization of things. What happens is the more phlegmatic people and totalitarian people eventually come around to points of view that are apparent to more sophisticated people at an earlier date. People have now come around to what the enlightened people were saying at that time.

But blacklisting is a very vague notion to most people, something they are only vaguely aware of. It was one of these special phenomena that occurred in show business and in colleges—certainly not the brunt of the country was involved. It was an issue of bitter concern to a small amount of people, really. And as it filtered to a wider audience, it dissipated. It will be curious to see how people respond to this movie.

KELLEY: It certainly portrays very graphically how people’s lives were ruined.

ALLEN: I hope so. I know the John Henry Faulk thing on television got a very low rating. That was with George C. Scott, too. So . . .

KELLEY: People who come to see Woody Allen jokes or Zero Mostel gags [Mostel plays second lead] will be surprised.

ALLEN: I think we have to dispel that myth up front because I think it will be disappointing to those people who pay their three dollars to hear jokes.

KELLEY: What’s it like for you starring but not directing?

ALLEN: I don’t love that. I happen to like Marty Ritt very much—I know I’m in good hands. But I want to say, “Let’s put the camera here, let’s use this take,” and he gets to say that. I miss it and would not want to do this much anymore. Maybe once in a great while, but it’s not my idea of a great time.

KELLEY: What kind of things were important to your political development?

ALLEN: Well, first of all, I’m not a very political person. I hate politics and don’t believe in political solutions as long-term things. I don’t think they work. The U.S. has never been able to admit a realistic perspective on itself. It’s never been able to transmit to students and citizens a sense of wrongness about some things, horribleness about some things, and sometimes terrificness about certain things. And there’s an enormous hypocritical sense of self-righteousness about it that I don’t like. And of course the U.S. government is prey to all kinds of repression and pressures and I’ve always hated that—but I’ve hated politicians as long as I’ve known them. I don’t approve of them. I don’t like them. I have a very negative view of politics in general.

KELLEY: And all politicians?

ALLEN: I have supported certain campaigns. I supported Lyndon Johnson, against Barry Goldwater quite actively. I played the Eiffel Tower—I was one of the people in Americans Abroad for Johnson because I was overseas at that time, and I did a show in Paris to raise money for Johnson.

I am one of the few comics that can say he’s worked the Eiffel Tower. And I supported McGovern, Eugene McCarthy and John Lindsay. I thought they were outstanding in certain ways. Even then, they’re basically politicians, but they were such enormous cuts above who they were running against.

KELLEY: Okay, you don’t believe in political solutions—to play Philosopher King for a moment, how would you effect change and what kind of change would it be?

ALLEN: I don’t think there can be significant changes until there’s an enormous restructuring of thinking in terms of philosophy, religion and issues that are deeper and more central—psychoanalysis rather than politics. Political functioning is always symptomatic treating—you have to treat the disease right alongside the symptoms. And politicians never do that. So it’s always sort of a patchwork thing—it gets down to power groups. There’s no coming to terms with life in the universe individually, so consequently political solutions express themselves in a very superficial way. Like the person who suffers from a depression, he thinks that by moving from New York to San Francisco that his life is going to change, when actually the problems go with him. The problems go with you from socialism to communism to democratic government. As Mort Sahl used to say, the issue is always fascism anyway. It’s always fascism under different titles against a basically humanitarian type of approach under different labels. It has nothing to do with countries or parties. What we need is an impulse toward humanitarianism that has got to arise in each person non-coercively. People have to be made to realize the obvious worth of honesty and integrity. And until that happens nothing is really going to happen.

KELLEY: But history is nothing but a chronology of oppressors oppressing the oppressed.

ALLEN: That’s economic rather than political. I see it this way—if the humanitarian impulse exists, then it’s irrelevant what economic system best expresses the needs of the community. It couldn’t matter less to me, from a functioning point of view, whether I was living in a capitalistic society or a communistic society if the basic thrust of the people, their impulses are humanitarian—whatever works best for your community to keep it going in a livable economy where it minimizes the poverty or eliminates it. What usually happens, though, is that “communism” and “democracy” easily become expressions not of democracy or communism but of totalitarian mentality.

KELLEY: What did Richard Nixon do for America?

ALLEN: He was a disgraceful criminal and I have only the worst feelings about him. He expressed in a certain way many of the feelings that the public had themselves. I think that when he won that election with that enormous majority in 1972 that the public somewhere down deep knew that they were voting for a guy that represented the worst impulses of the United States and their own worst impulses. That goes back to the cliché that the people get the government they deserve. They did. That was a very unhealthy period for the United States. It was obvious to me that Nixon was only really pressured heavily when it looked like people who had things to gain were going to lose them because of the embarrassment he was causing.

And Ford was the guy who I remembered being on the wrong side of every issue—utterly unqualified to be president of the United States by any stretch of the imagination. All the talk that he’s a decent guy—I don’t see it that way. He’s decent to the extent that he’s not as overtly totalitarian as the Nixon group. But his impulses are not generous—and I think it’s important for a president to be overly generous.

KELLEY: Were you active at all in the antiwar movement?

ALLEN: To the moderate degree a performer can be. But nothing approximating the genuinely courageous behavior of draftees who refused to serve.

KELLEY: How did you beat the draft?

ALLEN: I was 4-F. I was psychologically unfit to serve. I took the physical—it was strange. I had all kinds of notes from all kinds of doctors, including an analyst, because I loathed the Army and wanted to do anything to get out. Every single doctor that I went to at the draft board would say “no evidence” to everything—claims to have asthma, flat feet—”no evidence.” When I went before the psychiatrist, oddly enough, he asked me to hold my hand out. I wasn’t trembling or anything, but my nails were so bitten—this is the exact truth—he said, “Do you always bite your nails like that?” I told him yeah, which I did, I wasn’t faking. And that got me out. That was it right there in a nutshell. That was the end of it—it was the happiest day of my life.

KELLEY: Do you regard yourself as a cynic?

ALLEN: Totally. You can tell from Love and Death—it’s a totally cynical movie.

KELLEY: Do you think cynicism and idealism can coexist in the same psyche?

ALLEN: Well, I do think they’re two sides of the same coin, like sadism and masochism. One gains the upper hand at a certain point. You’re possessed with a sense of idealism. Then it gets shattered and you go through a valley of cynicism.

KELLEY: It’s kind of the American schizophrenia—there’s always the hope that you can change if and at the end there’s the same old shit.

ALLEN: Exactly. It’s tantalizing. America, of all countries, has had the potential and has the potential to really achieve tremendous ends. It’s right at our fingertips and all we have to do is make a little effort—but we get waylaid by the temptation of greed and fear.

KELLEY: Who are your heroes?

ALLEN: I have a lot of heroes, but they’re all unconventional. Sugar Ray Robinson, Willie Mays, Louis Armstrong, Groucho, Ingmar Bergman . . . I’m such a great fan of the Marx Brothers. I guess I like anarchy down the line. I like anarchy and I like that the individual is responsible totally for his own choice of behavior. One hopes that the individual is so educated and so mature they will choose, all the time and under no compulsion, the humanitarian course. The anarchy of the Marx Brothers was exhilarating. My heroes are all pure heroes. They re not diluted with the problem of politics.

KELLEY: Have you met or wanted to meet any of them?

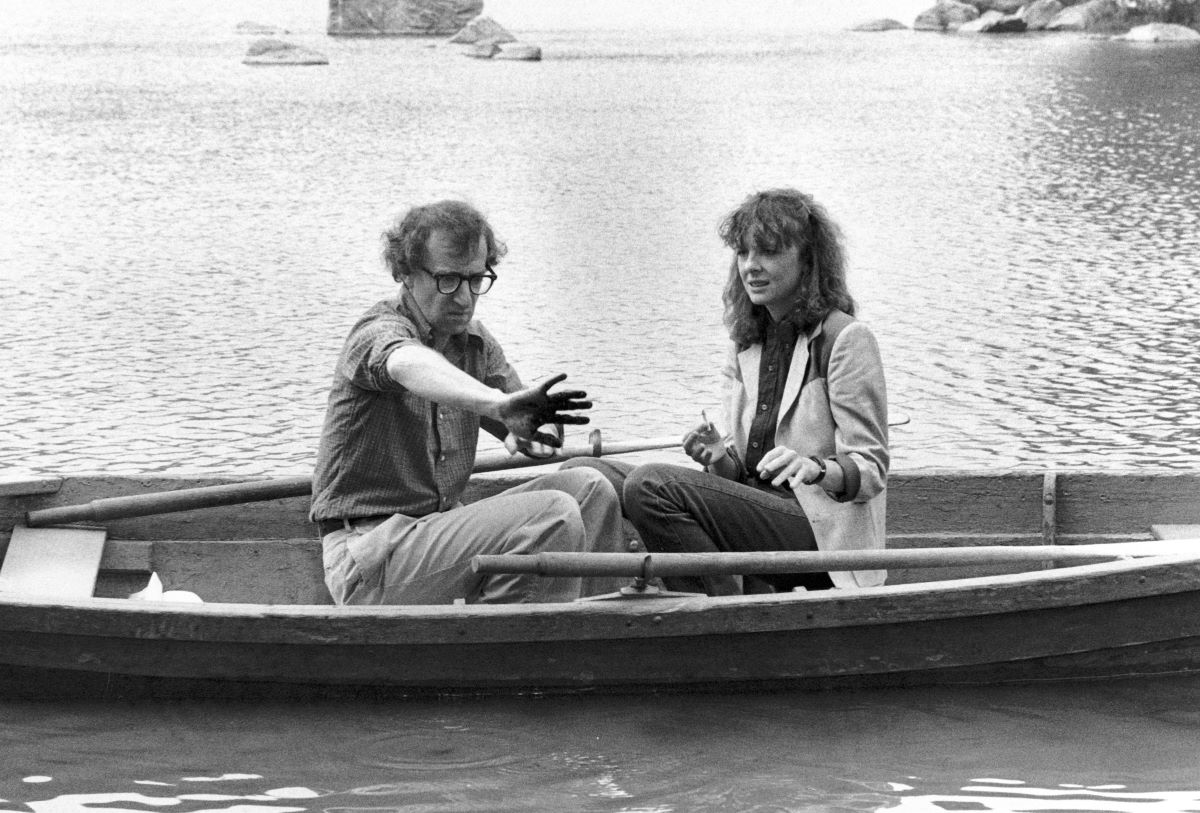

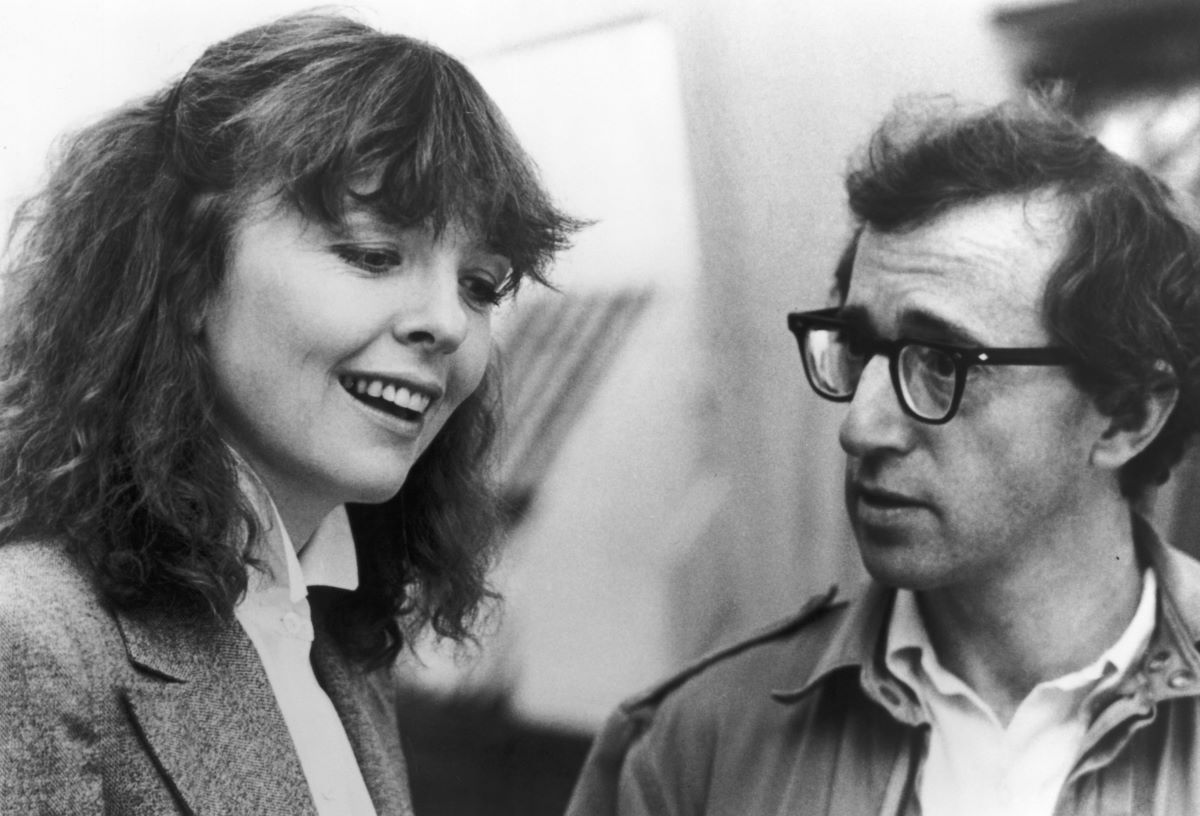

ALLEN: I don’t like meeting heroes. There’s nobody I want to meet and nobody I want to work with—I’d rather work with Diane Keaton than anyone—she’s absolutely great, a natural.

KELLEY: When you were growing up, who were your comedic influences? Kaufman and Hart, or Thurber, or . . .

ALLEN: Yes, Kaufman and Hart—George Kaufman, basically. I was a great fan of his when I was growing up. I’ve started to outgrow that style a little, but I thought he was an enormously amusing commercial playwright. And S. J. Perelman—all the time.

KELLEY: You have a touch of Perelman’s wryness.

ALLEN: I adore Perelman’s work. And Benchley. I appreciated Thurber but not really with great heart. But Perelman was just a knockdown, drag- out, hilarious writer, and still is to this day, relentlessly hilarious. When I was younger I got a real kick out of Max Shulman’s books, but he and Benchley were writing just for laughs—I appreciate that enormously. When I write for the New Yorker now, basically, I’m always trying to just be funny.

KELLEY: How about Lenny Bruce?

ALLEN: I met him twice, I wasn’t a friend of his. I caught his show in the latter part of his career. I’ve heard some of his albums. I saw him a couple of times on television. He was not my taste. I have nothing against him or anything and I certainly thought that he was far, far finer in what he was going for than the people who were persecuting him, and in that sense I took his side. But as a creative comedian he wasn’t to my taste. I didn’t find him particularly funny, and I certainly didn’t find his insights and ideas interesting, original or particularly intelligent. I just didn’t enjoy him. Whereas someone like Mort Sahl I enjoyed enormously. I thought he was quite brilliant and hilarious and fresh, an interesting thinker. Also at that time I thought Nichols and May were a brilliant comedy team, very perceptive and gifted. I just got no kick out of Lenny, though.

KELLEY: What about Richard Pryor?

ALLEN: I haven’t seen him in years—six or so. I’m sure I would like him because I’m a great audience for comedians. I find Jonathan Winters to be very funny—a great, great funny man.

KELLEY: Lily Tomlin?

ALLEN: I caught part of her TV special. I was not crazy about her on Laugh-In because I didn’t like that program—I didn’t like what they made her do. But I liked her very much on her special. I thought she was quite brilliant and very attractive. She is funny and also very sexy and appealing.

KELLEY: Does the kind of contemporary material Pryor and Tomlin do make you feel old-fashioned?

ALLEN: Without making any value judgment, it would be impossible for me to do the type of material they do. I think they’re lucky in one respect because I think that what they’re dealing with is more commercial. And I think that is in a good sense a tribute to them, that their concerns are social concerns and everyday life concerns and personal concerns. They communicate with people very well. Mine are more cerebral, and consequently less communicable and less commercial. There’s just nothing you can do. It’s the difference between innocent college kids with typical social petulance—as Fellini said, “I’m too old to change.” Fellini is obsessed with those issues that obsess him, Bergman has his, the ones that interest me just interest me and that’s it.

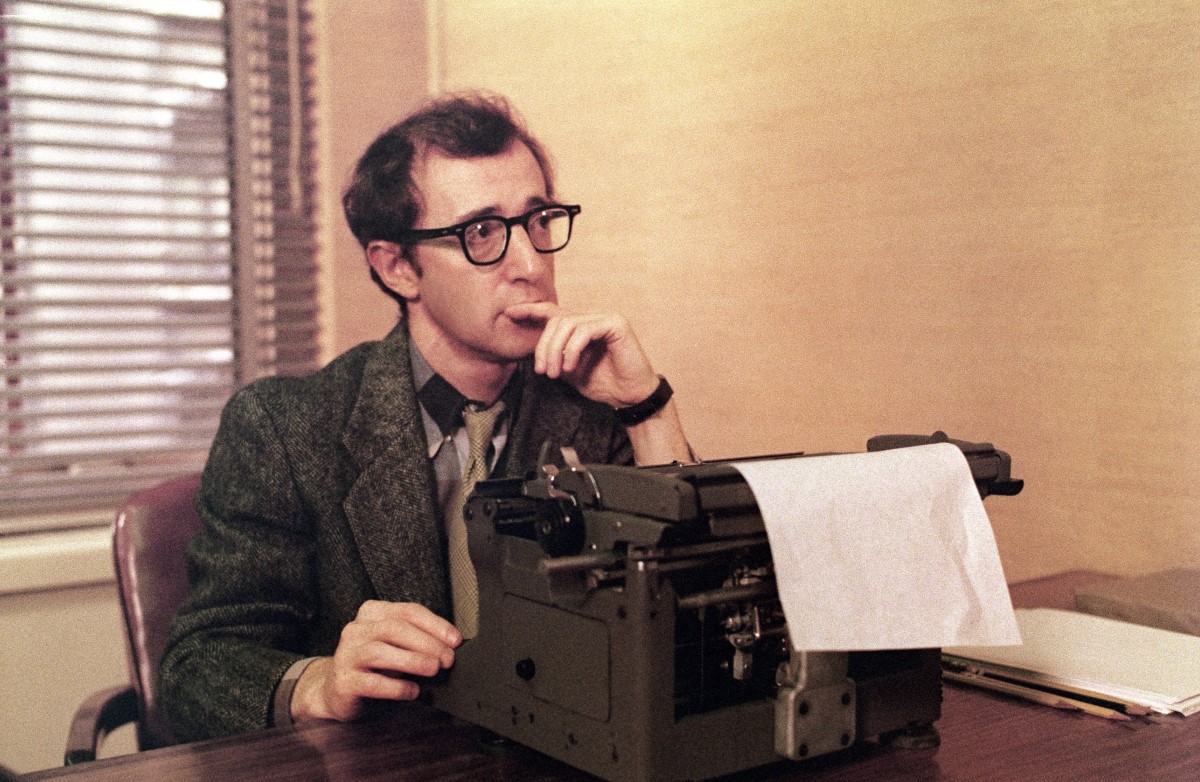

KELLEY: When you write, do you write constantly, or piece by piece?

ALLEN: Both. Sometimes I’ll have a terrific idea for a comic piece and I’ll write it the second I get a free minute. And then other times, if I haven’t been writing for the New Yorker for a few months, my guilt bothers me so much … I could be happy doing nothing but writing for them.

KELLEY: Do you ever suffer from writer’s block?

ALLEN: Not a block, not even remotely blocked. I have times when I can’t think of anything because, simply in the creative process, I can’t come up with it. I strike out just like anybody else—but no block, there’s nothing psychological about it. I think if you’re a legitimate writer and you have something to say a good creative impulse, you can’t not write. You experience it the other way—you can’t wait to get back to the typewriter, even though it’s hard, and not fun. You spend hours and days when nothing comes. But your impulse is to do it rather than avoiding doing it.

KELLEY: Have you ever gotten any flack from the way you portray women in your movies?

ALLEN: I haven’t had any problem at all—I think I portray everybody equally cynically. The funny thing about Love and Death—while I got the girl, I also died at the end.

KELLEY: What about the women’s movement?

ALLEN: Pretty much everything women are saying has made sense—they have been shabbily treated. There has got to be a change of the relations of the sexes. And sexuality has nothing to do with the way anyone’s been brought up to feel about it. Everything you’ve been told about sex up until this point is wrong.

KELLEY: Is the rise of bisexuality a product of confusion or liberation?

ALLEN: My instincts are—I could be wrong; I’m not making any pronouncements—that it’s a negative thing. But I’m much too ignorant on the subject to be confident of that. I’m just giving you my first reactions. I guess obviously a bisexual’s first reaction would be one, and a heterosexual’s another. But my instincts say that bisexuality is not an advancement. Now I do feel, naturally, in the case of homosexuality and bisexuality—as in all issues, such as the legalization of marijuana—that it should be an absolutely effortless thing of total free choice by anyone, with no kind of stigma legally or in any way at all. I do see it as symptomatic of negative forces, unhealthy forces. But I have an open mind about it.

KELLEY: You ever smoke pot?

ALLEN: Yeah, once or twice.

KELLEY: It didn’t do anything for you?

ALLEN: It did, but that’s not why I don’t smoke it. Alcohol does something for me, but I don’t drink it. I just don’t like the idea of marijuana or drugs, or pills—any of that stuff. I occasionally have wine, but not too often, usually when I’m with a girl or something.

KELLEY: The strongest you go is milkshakes?

ALLEN: Malteds. Sometimes I also have wine with dinner.

KELLEY: Is it a sign of further decay that so many people are into so many kinds of drugs?

ALLEN: I think so. I think marijuana is a bad sign, that drugs are certainly a bad sign, just as alcohol is. Of course, I do admit it’s to degrees, but to the lesser degree it’s not as bad a sign.

KELLEY: So how do you relax?

ALLEN: If I can’t relax naturally—watch a basketball game, play or listen to jazz—if I can’t relax normally, I’d rather not relax.

KELLEY: You have a narc who plays in your band, right?

ALLEN: Yeah, I shouldn’t say anything about it but it’s true.

KELLEY: Have you played for a long time?

ALLEN: I’ve played clarinet since I was fifteen.

KELLEY: What kind of jazz do you listen to—Coltrane?

ALLEN: I’ve got a lot of Coltrane, an enormous amount of that kind of jazz—Miles, Charlie Parker, Monk. Also avant-garde stuff, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor. But I’m not as interested in that stuff as I was—I love all those guys—but I’m more interested in New Orleans-style jazz.

KELLEY: Like Kid Ory?

ALLEN: Yeah, all the time. I met Kid Ory once. In New Orleans. He thought I was a girl. He wanted to tell a dirty joke and I had long hair at the time and he said he wouldn’t tell it with “her” in the room.

KELLEY: You never listen to rock ‘n’ roll?

ALLEN: Never.

KELLEY: What is love?

ALLEN: I don’t know. It’s a very tough question. There are many different kinds of love and the only love I’m really interested in is the love between a man and a woman. So that’s the one one concentrates on. That’s the most difficult one.

KELLEY: There’s a line in Love and Death—“Don’t forget love between two women. That’s always been one of my favorites.”

ALLEN: That’s right. There were a lot of references to that. It was pointed out to me that there were several references in that movie to that kind of sexuality, but it was inadvertent. I just don’t know anybody that has a good relationship for any length of time. I just don’t. That’s another area where I’m very cynical. Everybody is dependent on love. Love is the result of the best kind of luck in the area of relations with the other sex. But strictly luck. There’s an enormous human conceit that we can influence things much more than we can. Hence, a guy is dressing for a date, he’ll say, “I’ll wear the brown jacket,” and then. “No, I’ll look better in the gray jacket.” Actually thinking that the difference is going to create an effect. Meanwhile the girl has decided a long time ago whether she’s going to bed with him. And the same, vice versa. The girl’s thinking. “I won’t appear too anxious.” And they’re all laboring under the conceit that you can influence things when actually those decisions are unconscious. People flounder around—it’s a very complicated subject that nobody has shed any light on, really.

KELLEY: I guess fifteen years ago you never thought you’d be idolized by millions of people.

ALLEN: Not only did I not think it then, I see absolutely no evidence of it anyplace now. It’s been said to me numerous times and there’s not a shred of evidence of it. My record albums have never sold, although the three albums I’ve come out with are among the best things I’ve ever done. I played college audiences when I was coming up strongly as a comedian, and I never drew. And my movies don’t get such an enormous audience. They get decent size, just moderate. I honestly don’t know who my audience is. I don’t think they’re necessarily college kids or New York people—it’s just a disparate group, not enormously large, that’s all I can think of.

KELLEY: Surely, though, you suffer from the perils of fame—you know, walking down the streets getting accosted by little old ladies.

ALLEN: Sometimes that happens. I’m not too crazy about that. It’s not an enormous problem. I disguise myself, I wear my hat down over my ears. It depends. Some days I get recognized, other days not at all.

KELLEY: Isn’t it a drag to be recognized?

ALLEN: Yes, it’s a drag, for me. Other people I know range from not minding at all, being very grateful for it, to actually liking it. I’ll go out with another actor and he won’t wear a hat or anything. It’s amazing. And I’m walking around with a brown paper bag on my head.

KELLEY: It seems to me the worst curse anyone can have is to be recognizably famous.

ALLEN: To have inoperable brain cancer is a bad one, too. Actually, we have a tendency to make enormous problems out of these things. I walk down the street and see a guy that’s blind, or a paraplegic, and I say to myself—what does he say to himself at night? I’m always whining and complaining about this guy’s bothering me or it’s raining, when there’s quite a few people who cope with utterly insurmountable problems, and I don’t know how they do it. It’s unfathomable to me.

KELLEY: Do you get upset when you see winos bleeding on the curb?

ALLEN: Sometimes. Sometimes living in New York you pass winos without seeing them and sometimes I’ve had genuine feelings of compassion. I go cover somebody with a newspaper—it depends on my mood of the day. You experience a sense of impotency. I get up in the morning, I have my coffee, I have to get down here to shoot the film, and on page one of the Times there’s news of a cholera epidemic in Bangladesh or something. And your heart is wrenched. You don’t know what to do. And the next thing you know the downstairs bell is ringing and it’s off to work. At times it’s occurred to me that the only life of any consequence would be a missionary life.

KELLEY: You should have been a Catholic. Say, were your parents atheists?

ALLEN: They were kosher. They sent me to Hebrew school for eight years.

KELLEY: Do you speak Hebrew?

ALLEN: Yes; I can read and write it.

KELLEY: [Kelley speaks a Hebrew phrase.]

ALLEN: That’s very good. I don’t understand what you said.

KELLEY: It means, “After you finish the ice cream continue straight toward the seashore.”

ALLEN: That’s very funny. How often do you use that?

KELLEY: You’d be surprised. Over the years I’ve found all sorts of ways of working it into conversation.

ALLEN: We never learned words like ice cream. It was all anxiety phrases. I hated every second of it. It was awful. My neighborhood was real religious.

KELLEY: Do you identify at all with Philip Roth’s Jewish characters?

ALLEN: I’ve read Roth and I’ve enjoyed him. I don’t personally relate to them. I don’t have that Jewish obsession. I use my background when it’s expedient for me in work. But it’s not really an obsession of mine and I never had that obsession with Gentile women.

KELLEY: You never wanted to be a rabbi?

ALLEN: Not in the remotest way. I’ve always found it a silly occupation.

KELLEY: Did your parents want you to be one?

ALLEN: No, they wanted me to be a pharmacist or a doctor, that kind of thing.

KELLEY: What did you want to be?

ALLEN: I never had any serious plans until my senior year. I wanted to be a baseball player. I was a Giants fan, but I came from the Brooklyn Dodger area, not far from Ebbetts Field. I wanted to play second base for the Dodgers very much. I wasn’t bad. And I wanted to be a magician—that fascinated me. I practiced for many, many hours. I can do a lot of it now, but then I used to practice for six or seven hours a day. And I thought of being a cowboy, an FBI man, a crime reporter. Then when I was about fifteen I realized I could write jokes. I was always kidding around—I liked comedians and was interested in them. One day after school I started typing jokes out and looking at them. And I immediately sold them at ten cents a crack to newspaper columns. I was just making them up and guys were printing them. And very briefly after that I got a chance to write for the Peter Lind Hayes radio show. I was working immediately so there was never any doubt about what I was going to do.

KELLEY: Was there ever any doubt about the existence of God?

ALLEN: I never thought about it seriously until I was a teenager, and then all feelings were negative from the start. I think the most important issues to me are what one’s values in life should be—the existence of God, death—that’s real interesting to me. Whether it’s a capitalist society or socialism—that’s superficial.

KELLEY: So what happens after death?

ALLEN: Most likely, nothing. Or something that’s utterly unfathomable to the human mind.

KELLEY: Do you believe in reincarnation?

ALLEN: I certainly don’t believe in anything. It’s conceivable, but I don’t believe in it. Perhaps we come back as a deck reshuffling itself. Maybe we turn into birds. Who knows?

KELLEY: What; then, is the meaning of life?

ALLEN: The meaning of life is that nobody knows the meaning of life. We are not put here to have a good time and that’s what throws most of us, that sense that we all have an inalienable right to a good time.

KELLEY: It’s in the Constitution—”life, liberty and the pursuit of a good time.”

ALLEN: The pursuit is all right. We can pursue it, but we were not put here to have one. That anxiety is the natural state of man, and so I think it’s probably the correct state. It’s probably important that we experience anxiety because it makes for the survival of the species. It doesn’t bother me that I’m not having a good time because I know I’m doing something right. Most people who are having a good time are paying an enormous price for it in some way.

KELLEY: Can’t you have a good time not having a good time, though?

ALLEN: Not a very good time, no. Because you’re always aware that the basic thrust in life is tragic and negative.

KELLEY: Did you ever go to college?

ALLEN: I was thrown out of NYU and then thrown out of CCNY the first year for not attending, bad marks. So I have no real college education. I don’t even have a year of college. But I was a motion pictures major I failed my major. I was not good in college.

KELLEY: Was that traumatic?

ALLEN: For my parents, not for me. I loathed every day and regret every day I spent in school. I like to be taught to read and write and add and then be left alone. I regret all the time I spent in public school. It was a blessing to be thrown out of college.

KELLEY: So who did you read?

ALLEN: Kafka, a lot I like. And Camus, Sartre, Kierkegaard. Anyone who’s got a basically hard line. I sometimes think that some of those French intellectuals like Sartre are just as crazy as the French film critics, and that in the end the unromantic English philosophers are much less interesting but much closer to the truth. It’s hard to argue with Bertrand Russell. The more you learn about life, the more you feel able to challenge what I consider romantic existentialist philosophers in the same sense that one challenges French film critics very easily because film is a simpler subject to understand. I’m also a great fan of Ionesco—I found his plays very amusing and imaginative. And I thought Genet’s The Balcony was a brilliant play and I think Beckett is superintelligent. I find him intellectually interesting, but I don’t like his plays. Though he is able to communicate a sense of absurdity and despair that resonates within me. Kafka, on the other hand, just gets to me totally—he’s the best reading.

KELLEY:Do you ever grow small warts in strange places?

ALLEN: No. I never had any excrescences on my body or skin at all. I’m physically great—perfect.

KELLEY: Is there anybody you really hate?

ALLEN: I hate all the standard villains. Hitler.

KELLEY: Simon Legree?

ALLEN: Yes, Simon Legree. I think probably if you start me thinking on that I could come up with an enormous list of people I hate.

KELLEY: Including Woody Allen?

ALLEN: I have, I think, an appropriate amount of self-loathing. And I think that’s important for everybody. I don’t trust people who are too confident about themselves. If it gets to be too much, you’re wallowing in self-pity, and then it’s no good. But to not take yourself seriously is important, to not think you’re so hot—because you’re not. The trick is to keep a very critical eye on yourself and not get upset if someone says you’re terrible, and not think it means anything at all if people say you’re dynamite.

KELLEY: What are you afraid of?

ALLEN: Sickness and death more than anything. My other fears are subsidiary to them—they cover a tremendous amount. I’d be much calmer if I didn’t have to face those things. The world would be better off if I didn’t have to face those things.

KELLEY: Are you a paranoid person?

ALLEN: I have a pessimistic view of people. Consequently, I have that view of myself. I think the worst in any given situation, so I think the other person is thinking the worst. The point is that paranoids are right a certain amount of the time. I guess that comes from my own feelings of hostility. I’m suspicious and negative. I feel others have to prove themselves to me, and I don’t make it any easier on myself. I feel I’m not accepted and that I have to prove myself in any situation, that one can’t take decency for granted, that you have to keep proving it to me.

KELLEY: How has psychoanalysis helped you?

ALLEN: It hasn’t helped me as much as I’d hoped. I’ve had three analysts, all Freudian. The only thing it’s helped me do really is to gain a slightly calmer perspective on things. I don’t get side-tracked on obsessional issues as much. I tend to question my feelings for various meanings rather than just accepting them at face value automatically.

KELLEY: Do you ever try and crack up your shrink?

ALLEN: No, I’m serious all the time. I practically never make jokes in general, anyplace.

KELLEY: No kidding. What are your long-term goals?

ALLEN: I’d like to keep growing in my work. I’d like to do more serious comical films and do different types of films, maybe write and direct a drama. And take chances—I would like to fail a little for the public. Not just for myself—I’ve already done that. I know I could make a successful comic movie every year, and I could write a comic play that would do very well on Broadway every year. What I want to do is go on to areas that I’m insecure about and not so good at. This next movie I’m going to do is very different than anything I’ve ever done and not nearly a sure thing. It will be much more real, and serious. The alternative is to do what the Marx Brothers did—which is a mistake for them, and they’re geniuses. That is, they make the same movie all the time—brilliant, but the same one. Chaplin grew, took chances, and failed—he did the right thing. That’s very important. Comedians fall into that trap very easily—they just hit a formula that works and they cash in on the same thing time and time again.

KELLEY: What’s your ultimate fantasy?

ALLEN: On the possible side, to make very interesting serious movies, as I said. On the impossible side, I fantasize playing guard for the Knicks and being black—if I had my life to live over again, among the things I’d like to be is a black basketball player. Or a concert pianist, a conductor, a ballet dancer—I’m a big fan of ballet and modern dance.

KELLEY: What’s your favorite color?

ALLEN: I like autumnal hues a lot—you can tell from Love and Death.

KELLEY: The photography in that movie was incredible.

ALLEN: My grasp of photography is getting better. That movie required it. You know, in Paris you get that weather all the time—foggy and gray. If you shoot in California, it’s sunny and it doesn’t look so nice.

Rolling Stone, July 1, 1976