by Pauline Kael

The Right Stuff gives off a pleasurable hum: it’s the writer-director Philip Kaufman’s enjoyment of the subject, the actors, and moviemaking itself. He’s working on a broad canvas, and it excites him—it tickles him. Based on Tom Wolfe’s 1979 book, the movie is an epic ramble—a reenactment of the early years of the space program, from breaking the sound barrier up to the end of the solo flights. It covers the years 1947 to 1963, especially the period after 1957, when government leaders, who felt they’d been put to shame by the Soviet Union’s sorties into space, rushed to catch up; they initiated Project Mercury, assembled a team of official heroes—all white, married males—and began to exploit them in the mass media. Henry Luce, the founder of Life, which had perfected the iconography of a clean-living America during the Second World War, bought exclusive rights to all NASA coverage of the space program and put the newly selected astronauts under contract; Life then presented them and their wives as super-bland versions of the boys and girls next door. The movie contrasts the test pilots who risk their lives in secrecy with these seven publicly acclaimed figures who replace the chimps that were sent up in the first American space capsules. They’re synthetic heroes, men revved up to act like boys. Walking in formation in their shiny silver uniforms, the astronauts, whose crewcuts give them a bullet-headed look, are like a football team in a sci-fi fantasy. But they’re not quite the square-jawed manikins they pretend to be; creatures of publicity, they learn how to manipulate the forces that are manipulating them. They have to, in order to preserve their dignity. They’re phony only on the outside. Their heroism, it turns out, is the real thing (which rather confuses the issue).

As the lanky Sam Shepard embodies him, Chuck Yeager, the “ace of aces’’ who broke the sound barrier in 1947, evokes the young, breathtakingly handsome Gary Cooper. And Yeager and the other test pilots have a hangout near the home base of the U.S. flight-test program: a cantina in the Mojave Desert, with a wall of photographs behind the bar —snapshots of the flyers’ fallen comrades. Presided over by a woman known as Pancho (Kim Stanley), the place recalls the flyers’ hangout in the Howard Hawks picture Only Angels Have Wings and the saloons in Westerns. Shepard’s Yeager is the strong, silent hero of old movies —especially John Ford movies. On horseback in the desert, he looks at the flame-spewing rocket plane that he’s going to fly the next morning, and it’s like a bronco that he’s got to bust. Kaufman uses Sam Shepard’s cowboy Yeager as the gallant, gum-chewing individualist. He has some broken ribs and a useless injured arm when he goes up in that fiery rocket, and he doesn’t let on to his superiors; he just goes up and breaks the sound barrier and then celebrates with his wife (Barbara Hershey) over a steak and drinks at Pancho’s. He expresses his elation by howling like a wolf.

Even if the actual, sixtyish Chuck Yeager, now a retired Air Force brigadier general, weren’t familiar to us from his recent appearances in TV commercials, where he radiates energy and affable good-fellowship, we can see him in the movie (he plays the bit part of the bartender at the cantina), and he isn’t a lean, angular, solitary type—he’s chunky and convivial. Sam Shepard is playing a legend that appeals to the director. He’s Honest Abe Lincoln and Lucky Lindy, a passionate lover, and a man who speaks only the truth, if that. This legendary Yeager has too much symbolism piled on him, and he’s posed too artfully; he looms in the desert, watching over what happens to the astronauts in the following years as if he were the Spirit of the American Past. Sam Shepard’s Yeager appears in scenes that have no reason to be in the movie except, maybe, that Phil Kaufman has wanted for a long time to shoot them. (The worst idea is the black-clad death figure, played by Royal Dano, who, when he isn’t bringing the flyers’ widows the bad news or singing at the burial sites, sits at a table in Pancho’s, waiting.) Kaufman must assume that the images of Yeager will provide a contrasting resonance throughout the astronauts’ sequences. But Sam Shepard isn’t merely willing to be used as an icon—he uses himself as an icon, as if he saw no need to act. And he can’t resonate—he isn’t alive. The movie is more than a little skewed: it’s Kaufman’s—and Tom Wolfe’s—dreamy view of the nonchalant Yeager set against their satirical view of Henry Luce’s walking apple pies. This epic has no coherence, no theme to hold it together, except the tacky idea that Americans can’t be true, modest heroes anymore—that they’re plasticized by the media.

Like Tom Wolfe, Phil Kaufman wants you to find everything he puts in beguilingly wonderful and ironic. That’s the Tom Wolfe tone, and to a surprising degree Kaufman catches it and blends it with his own. The film’s structural peculiarities and its wise-guy adolescent’s caricature of space research all seem to go together to form a zany texture. It’s a stirring, enjoyable mess of a movie. Kaufman plays A/ad-magazine games, in which the woman nurse (Jane Dornaker) testing the astronauts is a comic ogre with a mustache and the space scientists are variants of Dr. Strangelove—clowns with thick German accents. (Scott Beach, who plays the Wernher von Braun figure, wears a wig that sits on his head like a furry creature that took sick and died there.) Counterculture gags are used for a sort of reverse jingoism. When the scientists get together to celebrate their victories, they sing in German. When Lyndon Johnson (Donald Moffat) can’t understand what von Braun is saying, he’s a Lyndon Johnson cartoon, and the dialogue has the rhythm of a routine by two old radio comics. Most of the low comedy doesn’t make it up to that level; Kaufman has a healthy appetite for foolishness, but his comic touch is woozy—some scenes are very broad and very limp. (Even Jeff Goldblum, as a NASA recruiter, can’t redeem all the ones he’s in.) And there are coarse, obvious jokes: the astronauts come on to the press like a vaudeville act—playing dumb and giving the reporters just what they want—while the Hallelujah Chorus rises on the soundtrack. The action zigzags from old-movie romance to cockeyed buffoonery to the courage (and exaltation) of men alone in tiny capsules orbiting the earth at eighteen thousand miles an hour. Kaufman relies on the contrasts and rhythms of the incidents to produce a cumulative vision, and it doesn’t happen. The picture is glued together only by Bill Conti’s hodgepodge score. But a puppyish enthusiasm carries it forward, semi- triumphantly. And the nuthouse-America games do something for it that perhaps nothing else could have done: they knock out any danger of its having a worthy, official quality, and they make it O.K. for the flights themselves to be voluptuously peaceful.

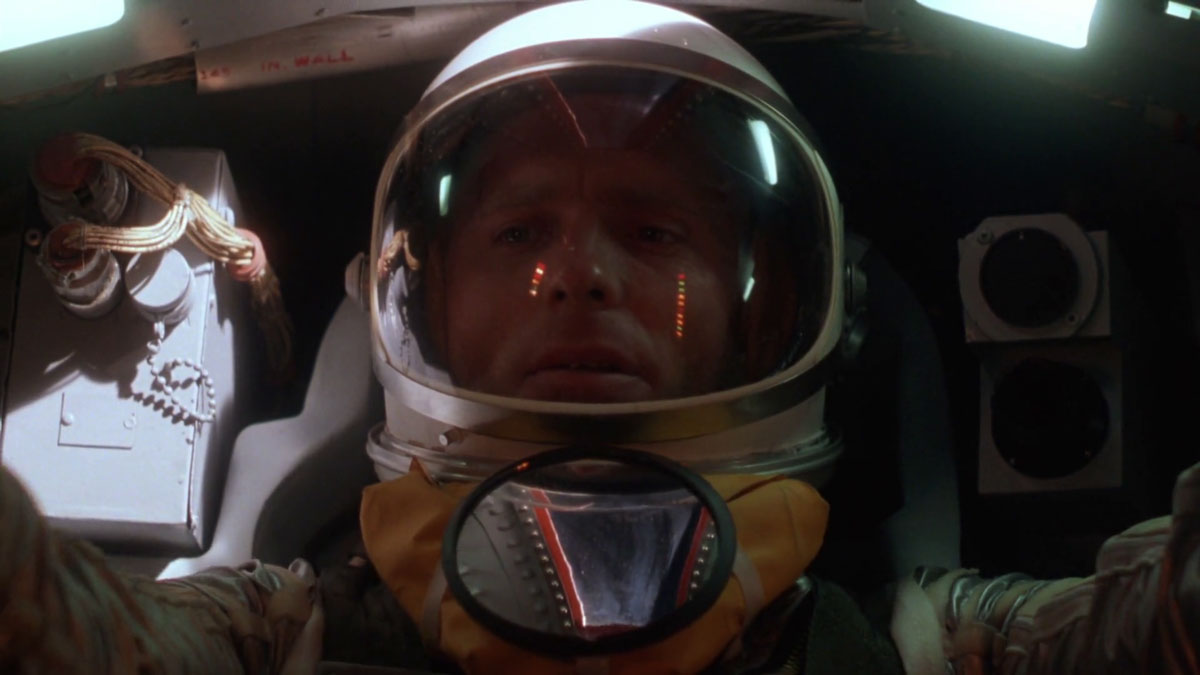

The flights—a mixture of NASA footage and fictional material, with marvellous sound effects—are inescapably romantic. Working with the cinematographer Caleb Deschanel (The Black Stallion) and with the San Francisco avant-garde filmmaker Jordan Belson, who does special visual effects, Kaufman provides unusually simple and lyrical heavenly scenes. As a scriptwriter, he may try to come in on a wing and a prayer, and as a director he may have too easygoing a style for the one-two-bang timing needed for low comedy, but he’s a tremendous moviemaker, as he demonstrated in The Great Northfield, Minnesota Raid (1972), The White Dawn (1974), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), and The Wanderers (1979). He has a puckish side; it comes out here in a rather unshaped deadpan joke using Australian aborigines to account for the mysterious “celestial fireflies” that Ed Harris’s John Glenn reports seeing. Kaufman’s re-creation of the middle and late fifties is realistic and affectionate without any great show of expense. (He was able to fake most of the locations in the San Francisco area, which doubles here for Florida, Texas, Washington, D.C., and New York, and Australia, too.) And he doesn’t take the bloom off space by knocking us silly with the grandeur of it all. The Right Stuff has just enough of Jordan Belson’s tantalizing patterns and rainbow fragments to suggest the bliss that Chuck Yeager felt high above the desert and that the astronauts experience while they’re inside their spinning capsules. Strapped in and almost immobile, John Glenn is also the beneficiary of a magical effect that he himself can’t see. The lights from the equipment that are reflected in the windows of all the astronauts’ helmets hit him just right; we see two tiny lines of jewelled lights streaking down his face, one from each eye. “Astro tears” the movie crew called them. (They suggest Jesus in space.)

Phil Kaufman makes it possible for some of his characters to show so many sides that they keep taking us by surprise—especially Ed Harris’s John Glenn, the strict Presbyterian, who probably comes the closest to fitting Life’s image of an American hero. This Glenn, who reprimands his teammates for their willingness to oblige astronaut groupies, and is grimly humming “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” to keep himself together as he sits trussed up in his capsule, hurtling back into the earth’s atmosphere, is perfectly capable of using patriotism as a put-on: at the Mercury team’s first big press conference, in Washington, he assumes the role of spokesman, flashes his quick, big smile, and is real pleased with himself. Blond and blue-eyed, and, at thirty-two, considerably younger than John Glenn was at the time, Ed Harris has some of the bleached pallor of Robert Duvall, and when he’s sitting out in space, loving it, his pale-eyed, staring intensity may remind you of Keir Dullea’s starchild face in 2001. But Harris has a scary, unstable quality that’s pretty much his own. He holds his head stiff on his neck, and he’s the kind of very still actor who can give you the willies: he often has the look of someone who’s about to cry, and a flicker of a smile can make you think the character he’s playing is a total psycho.

Your feelings about Harris’s Glenn are likely to be unresolved, except in Glenn’s scenes with his wife, Annie (played with delicate, grinning charm and mischief by Mary Jo Deschanel, the actress wife of the cinematographer). In an early scene, Kaufman establishes that they have an understanding of each other that goes beyond words. It has to, because the enchanting Annie is a stutterer who can’t get a sentence out.

Her husband knows how to read every blocked syllable; the two of them are so close they communicate almost by osmosis, and even when she’s making fun of his gung-ho wholesomeness he giggles happily, secure in the intimacy they share. Then, on the day of his scheduled flight, the NASA people ask him to talk to his wife on the phone and persuade her to “play ball” with the television newscasters who are outside the Glenns’ house waiting to come in and interview her. Vice-President Johnson is also out there, in his limousine; he wants to come in to reassure her on TV. On the phone, she’s distraught—she can barely speak her husband’s name. But he intuits what she’s trying to say; it’s as if he could read her breathing. She faces terrible humiliation—she wants to know if she has to let them all in. Glenn has the single most winning speech of the whole three-hour-and-twelve-minute movie when he tells her that no, she doesn’t have to let anybody in. And, good Presbyterian that he is, he manages to express his rage at the networks and the politicians without ever using a cussword (which is a feat comparable to her non-verbal communication—they’re both handicapped). The scene is perhaps the wittiest and most deeply romantic confirmation of a marriage ever filmed. When Glenn is back on earth and the two of them are riding in a ticker-tape parade in his honor, they’re a pair of secret, victorious rebels.

The movie probably has the best cast ever assembled for what is essentially a docudrama—although a twenty-seven-million-dollar docu-drama, and one with an individual temperament, isn’t like anything we’ve seen on TV. Scott Wilson appears as the test pilot Crossfield, and Levon Helm is Ridley, Yeager’s mechanic. Pamela Reed brightens up the scenes she’s in; she’s all eyes as Trudy, the secretly estranged wife of the astronaut Gordon Cooper. And I felt my face twitching, as if I were about to laugh, whenever Dennis Quaid’s Gordo was on the screen, because he has a devilish kid’s smile, with his upper lip a straight line across his face. Quaid plays Gordo as a self-reliant, tough kid—a wised-up Disney boy, the savviest Huck Finn there ever was. When he gets his turn in the heavens—Cooper makes the last solo flight into space—his split-faced grin is perhaps the standout image of the film. He’s cynical and cocky—a materialist in every thought and feeling—and so when his face tells us that he’s awed by what he sees, we’re awed by what we see in his face. It may seem ungrateful to point out the results of realism, but most of the actors playing astronauts are martyred by their haircuts; their features look naked, their noses as big as a bald eagle’s beak. Scott Glenn, who plays Alan Shepard, has gone even further than the others. He looks a little like Hoagy Carmichael, but he seems to be deforming himself; if this is meant to be an aspect of the astronaut’s character, it isn’t delved into. Scott Glenn has got so wiry, gaunt, and muscular that his skin appears to be pulled taut against his bones, and when he laughs his whole face crinkles, like a hyena’s.

If we’re often preoccupied by the men as physical specimens, this has a good deal to do with the subject, but it may also be because we’re not sure how to interpret their meaningful glances at each other. Are we intended to see comradeship there, and mutual respect, or do the expressions mean “They’re buying it!” or “This is the life!” or “My head is numb”? We in the audience are put in the position of being hip to what’s going on even when we don’t really get it. What, for example, are the astronauts thinking as they watch old Sally Rand do her feather-fan dance in their honor in Houston in 1962? (The dancer who impersonates her is, blessedly, younger and more gifted.) The jazzy hipness in the film’s tone comes down to us from Tom Wolfe—it’s an unearned feeling that we’re on to things. Probably Kaufman thinks that he’s conveying a great deal more to us than he is. Certainly he’s trying to “say something” when he cuts Sally’s fan dance and the expressions of the astronauts watching her right into footage of Sam Shepard’s Chuck Yeager being brave again (and still unsung). But he’s making points on an epic scale rather than telling an epic story. He hasn’t dramatized what he wants to get at; he has attitudinized instead—setting the modern, hype-bound world against a vision of the past that never was. Though it’s a docudrama and some incidents are included simply for the record, The Right Stuff is drawn not from life but from Tom Wolfe’s book and Kaufman’s nostalgia for old-movie values.

The mishap that the astronaut Gus Grissom (that terrific actor Fred Ward) is involved in gives us, briefly, something solid that makes us feel very uncomfortable. As the film presents it, the gloomy-souled Grissom panics during the splashdown of his capsule and is desperate to get out. The helicopter that is to pick up the capsule is hovering overhead, maneuvering into position. Though the film doesn’t make it absolutely clear, when the hatch blows open and Grissom climbs out (and the capsule sinks) the implication is that he opened it. He claims that it simply malfunctioned and opened by itself, but clearly the NASA people don’t accept his account, because he receives considerably less than a hero’s welcome, and his wife, Betty (Veronica Cartwright), feels horribly let down by the second-rateness of the ceremonies in his honor. I wish that Kaufman had followed through on the disturbing, awkward quality of this incident, which grips us at a different emotional level from the other scenes. I realize I’m asking for a different kind of movie, but if he’d taken a different approach to the Gus and Betty Grissom episode he might have opened up some of the implications of the phrase “the right stuff” that have bothered me ever since Tom Wolfe’s book came out.

Yeager is, of course, the movie’s archetype of “the right stuff”—the model of courage, determination, and style. The astronauts don’t have an acceptable style, but the movie half forgives them, because, as it indicates, this isn’t their fault—the times are to blame. The men themselves have the guts and the drive, and they win Kaufman’s admiration. But then there’s Fred Ward’s Gus Grissom, who may at a crucial moment have failed to demonstrate “the right stuff.” Isn’t this all painfully familiar? Doesn’t it take us back to the Victorian values of The Four Feathers and all those other cultural artifacts which poisoned the lives of little boys (and some girls, too), filling them with terror that they might show a “yellow streak”?

Being far more of an anti-establishmentarian than Tom Wolfe, Kaufman probably felt that he had transformed the material, but he is still stuck with its reactionary cornerstone: the notion that a man’s value is determined by his physical courage. You’d think that Kaufman would have got past this romantic (and perhaps monomaniacal) conception of bravery. (With this standard, whatever you fear becomes what you compulsively measure yourself by.) I assume that people who are jellyfish about some things may be very brave about others. And certainly during the counterculture period there was a widespread rejection of the idea of bravery that this film represents. According to Wolfe, “the right stuff” is “the uncritical willingness to face danger.” Yet the film’s comedy scenes are conceived in counterculture terms.

The movie has the happy, excited spirit of a fanfare, and it’s astonishingly entertaining, considering what a screw-up it is. It satirizes the astronauts as mock pilots, and it never indicates that there’s any reason for them to be rocketing into space besides the public-relations benefit to the government; then it celebrates them as heroes. As a viewer, you want the lift of watching them be heroic, but they’re not in a heroic situation. More than anything else, they seem to be selected for their ability to take physical punishment and accept confinement in a tight cylinder. And about the only way they can show their mettle is by not panicking when they finally get into their passive, chimp positions. (If they discover that they’re sick with terror, they can’t do much more about it than the chimps could, anyway.) It’s Yeager who pronounces the benediction on the astronauts, who tells us that yes, they are heroes, because they know (what the chimps didn’t) that they’re sitting on top of a rocket. (I imagine that the chimps had a pretty fair suspicion that they weren’t frolicking high in a banana tree.) If having “the right stuff” is set up as the society’s highest standard, and if a person proves that he has it by his eagerness to be locked in a can and shot into space, the only thing that distinguishes human heroes from chimps is that the heroes volunteer for the job. And if they volunteer, as they do in this film, out of personal ambition and for profit, are they different from the chimp who might jump into the can eagerly, too, if he saw a really big banana there?

New Yorker, October 17, 1983